!Корпоративное право 2023-2024 / 2013-study-analysis_en

.pdf

COMPARATIVE-ANALYTICAL PART

Introduction – Mapping Directors’ Duties

The following part of the report contains the summary findings of the study. We This part has been designed drawing on the results of our stocktaking exercise, relying in particular on the country reports and the additional input received from our Country Experts and Country Researchers,1 as well as the input received by the Steering Committee, the discussions during our Steering Committee Conference and our discussions with the Commission.

Our primary goal is to highlight common features as well as the difference between the approaches taken by EU Member States in regulating directors’ duties. Given the substantial differences in legal traditions and regulatory techniques between Member States on the one hand, and the similarities of the legal and economic problems this central part of company law tries to address on the other, we adopt a functional approach in our analysis.2

In light of the aims of this study and having regard to its usefulness for assessing the necessity for, and the viability of, any potential future harmonisation in this area of law, we take the view that it is essential to identify functional equivalents across jurisdictions, and analyse their real-life effect on the operation of national company law.

This part thus goes beyond describing different regulatory approaches relating to the accountability of directors; the aim is to compare both the legal techniques used, and their outcomes. The value of this approach is underlined by the fact that we find both – close similarities in outcomes despite fundamental differences in regulatory techniques, as well as significant differences in the effect of seemingly similar rules.

This part is organised as follows. Part 1 sets the scene by providing an overview of the board structures used across the EU, including the role of employee representatives on corporate boards.

Part 2 describes the substantive provisions on directors’ duties, including the different regulatory approaches relating to directors’ duties and the addressees of the duties. This part also provides information of how different Member States define the

“interests of the company”, a concept that often serves as the central reference point for defining the behavioural expectations towards company directors. Furthermore it describes in detail how Member States define and enforce the duty of care and the duty of loyalty for company directors, and to what extent director liability can be excluded or limited.

Part 3 contains a summary of the relevant enforcement mechanisms, and attempts to identify relevant legal factors for what is widely perceived as under-enforcement of directors’ duties. To complement our stocktaking exercise, which mainly focussed on obtaining information on the legal rules in place

1See the lists of contributors in Part I. of this report.

2For a discussion of the merits of, and the problems connected with, the “functional method”, see e.g. R Michaels, “The Functional Method of Comparative Law” in: Law M Reimann and R Zimmermann (eds), The Oxford Handbook of Comparative Law (Oxford: Oxford University Press 2006) 339-382.

1 Directors’ Duties and Liability in the EU

across Europe, we conducted a number of interviews with corporate law practitioners from a number of Member States. The additional information obtained through these interviews is also described in Part 3.

Part 4 deals with directors’ duties once the company approaches insolvency. The main findings of this part of the study, however, have been used in Part 5, which highlights the main problems arising from the establishment and operation of companies across frontiers.

Each of the following sections starts by summarising the findings from our stocktaking exercise by categorising the legal approaches according to their main regulatory aims and their likely effect. The results are then visualised – necessarily in simplified form – by literally “mapping” the most significant regulatory groups. After that, we provide a short interpretation and analysis of our findings.

To complement our presentation of the data collected in our stocktaking exercise, we circulated a number of hypothetical cases among our country experts, and where relevant reference is made to the answers we received to these hypotheticals.

2 Directors’ Duties and Liability in the EU

1. The Organisation and Structure of Boards

1.1 Relevance of board structure

As part of our stocktaking exercise, we looked at the differences in board structures available and in use across the EU. These structures can have an important impact on the functioning and performance of a board,3 including a board’s attitude towards risk.4 The structure and composition of boards has also been shown to be related to a number of firm characteristics.5 Despite recent trends of regulatory convergence regarding board structures,6 we still find a significant degree of variation between the company laws of the EU Member States. The variation exists in the basic board structure (especially with regards to the distinction between one-tier and two-tier boards), as well as in relation to other aspects of company board makeup, such as election/nomination rights and the participation of employees.

Differences in board structures can have a significant impact on both the extent and content of directors’ duties and liabilities, as well as on the enforcement of these duties.7 First, the structure of a company’s board determines the main elements for the allocation of decision-making powers – and, consequently, responsibility for the decisions – within a company. Second, to the extent that a legal system also relies on enforcement of directors’ duties through the company organs itself, a formal division of responsibilities between different types of board members may be seen as having the effect of creating incentives for holding managers to account.8

The same is true for corporate ownership structure,9 which – for listed companies – also differs significantly across Europe.10 Indeed, the vast majority of corporate law practitioners we interviewed as part of our fact-finding mission stressed the fact that concentrated shareholder structures are an important factor explaining perceived low levels of enforcement of directors’ duties.11 In particular, the direct or indirect involvement in the managerial decision-making process by controlling shareholders of both listed and non-listed firms seems to act as a powerful disincentive for the enforcement of directors’ duties outside insolvency.

3See e.g. KJ Hopt, ‘Modern Company and Capital Market Problems: Improving European Corporate Governance after Enron’ in: J Armour and JA McCahery (eds.), After Enron: Improving Corporate Law and Modernising Securities Regulation in Europe and The U.S. (Hart: Oxford 2006) 445, 453; PL Davies “Board Structure in the UK and Germany: Convergence or Continuing Divergence?” (2001) 2 International and Comparative Corporate Law Journal 435; C Jungmann, ‘The Effectiveness of Corporate Governance in One-Tier and Two-Tier Board Systems: Evidence from the UK and Germany’ (2006) 4 European Company and Financial Law Review 426; RB Adams and D Ferreira, ‘A Theory of Friendly Boards’ (2007) 62 Journal of Finance 217.

4See e.g. AB Gillette, TH Noe and MJ Rebello, “Board Structures Around the World: an Experimental Investigation” (2008) 12

Review of Finance 93-140.

5See e.g. A Boone, L Field, J Karpoff, and C Raheja, ‘The Determinants of Corporate Board Size and Composition: An Empirical Analysis’ (2007) 85 Journal of Financial Economics 66.

6See e.g. PL Davies “Board Structure in the UK and Germany: Convergence or Continuing Divergence?” (2001) 2 International and Comparative Corporate Law Journal 435; KJ Hopt and PC Leyens, “Board Models in Europe – Recent Developments of Internal Corporate Governance Structures in Germany, the United Kingdom, France, and Italy” (2004) 1 European Company and Financial Law Review 135.

7See e.g. KJ Hopt and PC Leyens, ibid.

8But see KJ Hopt and PC Leyens, ibid 142, pointing towards the reluctance of supervisory board members in a two-tier system to bring actions against management board members, as this would often entail admittance of a breach of the supervisory boards’ duty to exercise control over the management. See also Adams and Ferreira, n 3 above.

9See e.g. S Thomsen, ‘Conflicts of Interest or Aligned Incentives? Blockholder Ownership, Dividends and Firm Value in the US and the EU’ (2005) 6 European Business Organization Law Review 201; CG Holderness, ‘A survey of blockholders and corporate control’ (2003) FRBNY Economic Policy Review 51.

10See e.g. M Faccio and LHP Lang, ‘The ultimate ownership of Western European corporations’ (2002) 65 Journal of Financial Economics 365; F Barca and M Becht (eds.), The control of corporate Europe (Oxford: Oxford University Press 2001); T Kirchmaier and J Grant, ‘Corporate ownership structure and performance in Europe’ (2005) 2 European Management Review,

11“Closely-held companies”“ are private or public limited companies with a small number of shareholders and, consequently, relatively high ownership concentration.

3 Directors’ Duties and Liability in the EU

1.2 Mapping board structures I: The choice between one-tier and two-tier boards

Summary of the country reports in tabulated form

Table 1.2.a: board structures in Europe

|

one-tier or two-tier board |

|

Country |

structure |

|

|

(public companies) |

|

|

|

|

Austria |

mandatory two-tier board |

|

structure |

||

|

||

|

|

|

Belgium |

one-tier board |

|

or mixed structure12 |

||

|

|

|

Bulgaria |

choice between one-tier and |

|

two-tier board structure |

||

|

||

|

|

|

Croatia |

choice between one-tier and |

|

two-tier board structure |

||

|

||

|

|

|

Cyprus |

one-tier board structure13 |

|

|

|

|

Czech Republic |

mandatory two-tier board |

|

structure |

||

|

||

|

|

|

|

choice between “Nordic |

|

Denmark |

model”14 and German-type |

|

|

two-tier board structure |

|

|

|

|

Estonia |

mandatory two-tier board |

|

structure |

||

|

||

|

|

|

|

choice between “Nordic |

|

Finland |

model” and German-type |

|

|

two-tier board structure |

|

|

|

|

|

choice between one-tier and |

|

|

two-tier board structure |

|

France |

in addition, in the one-tier |

|

structure the company may |

||

|

||

|

choose between the PDG |

|

|

model15 |

|

|

|

|

Germany |

mandatory two-tier board |

|

structure |

||

|

||

|

|

|

Greece |

one-tier board structure |

|

|

|

|

Hungary |

choice between one-tier and |

|

two-tier board structure |

||

|

||

|

|

|

Ireland |

one-tier board structure16 |

|

|

|

|

Italy |

choice between three |

|

different board structures17 |

||

|

|

12Under Belgian law, the board of directors may transfer some of its power to a “direction committee”, which consists of both directors and non-directors.

13Cypriot company law is based on the UK Companies Act 1948. As under the law of the United Kingdom, the argument can be made that a degree of choice exists in relation to board structures. See also n. 25 below.

14See the description of the “Nordic Model” below.

15The PDG or “président-directeur general”-model combines the offices of the CEO and the chairman of the board, which in turn has consequences on removal rights; see below Section 1.5.

16Irish company law is similar to the law of the United Kingdom; hence, a degree of choice may exist in relation to board structures. As a matter of fact, Irish companies do, however, invariably adopt a one-tier board structure; see also n. 25 below.

4 Directors’ Duties and Liability in the EU

|

one-tier or two-tier board |

|

Country |

structure |

|

|

(public companies) |

|

|

|

|

Latvia |

mandatory two-tier board |

|

structure |

||

|

||

|

|

|

|

choice: supervisory board |

|

Lithuania |

and/or board of directors are |

|

optional under Lithuanian |

||

|

||

|

law |

|

|

|

|

Luxembourg |

choice between one-tier and |

|

two-tier board structure |

||

|

||

|

|

|

Malta |

one-tier board structure |

|

|

|

|

Netherlands |

choice between one-tier and |

|

two-tier board structure18 |

||

|

|

|

Poland |

mandatory two-tier board |

|

structure |

||

|

||

|

|

|

Portugal |

choice between three |

|

different board structures19 |

||

|

||

|

|

|

Romania |

choice between one-tier and |

|

two-tier board structure |

||

|

||

|

|

|

Slovakia |

mandatory two-tier board |

|

structure |

||

|

||

|

|

|

Slovenia |

choice between one-tier and |

|

two-tier board structure |

||

|

||

|

|

|

Spain |

one-tier board structure |

|

|

|

|

Sweden |

“Nordic model”20 |

|

|

|

|

United Kingdom |

one-tier board structure21 |

|

|

|

17Italian company law allows companies to choose between the “traditional” model with a board of directors and a board of statutory auditors, as well as a typical two-tier and a typical one-tier system. The prevalent choice, i.e. the traditional system, can probably best be described as a special form of a one-tier board structure. See the Italian report, Annex, Section 1.3, for details on the three board structures.

18While companies may generally adopt either structure, after exceeding certain size-related thresholds, companies are obliged to adopt a two-tier board.

19Portuguese company law allows companies to choose between the a structure with a board of directors and an audit board, as well as a typical two-tier and a typical one-tier system. The prevalent choice is best described as a special form of a one-tier board structure, in our view. See the Portuguese report, Annex, Section 1.3, for details regarding the available board structures.

20See the description of the “Nordic Model” below.

21UK company law does not contain mandatory rules as to a company’s board structure, arguably allowing shareholders to

adopt a structure that resembles a typical two-tier board; see PL Davies and S Worthington, Gower and Davies’ Principles of Modern Company Law (9th ed., London: Sweet & Maxwell 2012) 14-65; PL Davies “Board Structure in the UK and Germany: Convergence or Continuing Divergence?” (2001) 2 International and Comparative Corporate Law Journal 435.

5 Directors’ Duties and Liability in the EU

Discussion

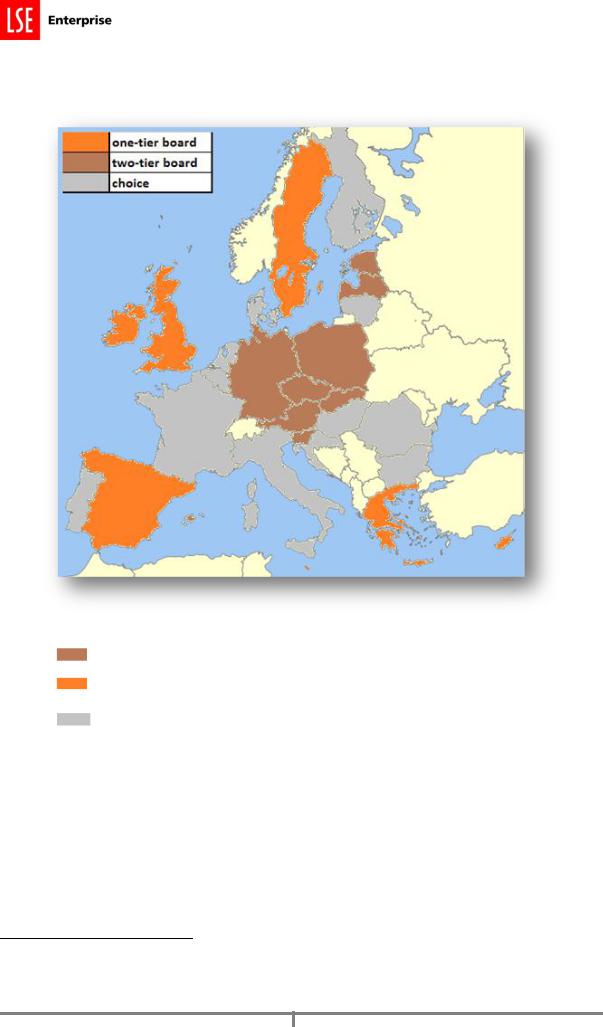

Map 1.2.a: Board structures in Europe

Legend |

Countries |

|

|

|

|

Mandatory two-tier board |

AT, CZ, EE, DE, LV, PL, SK |

|

|

|

|

One-tier board |

CY, EL, IE, MT, ES, SE, UK |

|

|

|

|

Choice |

BE, BG, HR, DK, FI, FR, HU, IT, LT, |

|

LU, NL, PT, RO, SI |

||

|

||

|

|

Board structures are usually classified into one-tier and two-tier structures, and it is this divide that has received most of the attention in comparative corporate governance debate. We find that a significant number of Member States provide national companies with a choice between the two systems. This

“choice” approach has increased in its importance since the introduction of the Societas Europea

(“SE”),22 which effectively enables incorporators across the EU to choose between oneor two-tier boards.23 Research relating to SE incorporations suggests that the added flexibility of governance (board) systems offered by the SE has been an important driver for the creations of SEs across

22Council Regulation (EC) No 2157/2001 on the Statute for a European Company (Societas Europaea – SE).

23See Art 38(b) of the SE Regulation. J Rickford, ‘Current Developments in European Law on the Restructuring of Companies: An Introduction’ (2004) 15 European Business Law Review 1225, 1240.

6 Directors’ Duties and Liability in the EU

Europe.24 It seems plausible that the recent trends of making available a choice of board structures for all public companies is related to these findings.

As of 2012, thirteen Member States permit companies to choose between oneand two-tier boards. These are Bulgaria, Croatia, Denmark, Finland, France, Hungary, Italy, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Portugal, Romania, Slovenia and, with some limitations, the Netherlands.

Only seven Member States (Austria, the Czech Republic, Estonia, Germany, Latvia, Poland, and Slovakia) require a two-tiered board, while eight Member States (Belgium, Cyprus, Greece, Ireland, Malta, Spain, Sweden, and the United Kingdom25) provide for one-tiered board structures.

There exists one important caveat in relation to our findings as reported above. While it is tempting to assume that the only significant divide between the board structures in different Member States’ is reflected in their choice between one-tier or two tier boards, a closer examination shows a more complex set of board structures in Europe. Under the typical “dualistic” model, a company has two distinct boards, one with purely supervisory functions and a management board responsible for the day-to-day management. Under the “monistic” model, on the other hand, the two functions are exercised by a unified board, such as typically the case under UK law.

However, the board structures in a number of Member States cannot easily be classified according to the “monistic” / “dualistic” divide. For example, Swedish company law prescribes a structure that we classify, in our description above, as being closer to a “one-tier structure”.26 However, the executive team (including the CEO) of Swedish companies are, in effect, not typically elected by the shareholders, but rather by the shareholder-elected board, which in turn monitors the executive team. Although there is no formally distinct “management board”, the Swedish structure can probably best be described as a hybrid form, incorporating elements of both the one-tier and the two tier system,27 although it still seems closer to the “monistic” model, given that the board has functions that go beyond purely supervisory tasks.28 This is reflected in the table above by classifying the Swedish board system as “Nordic Model”. Denmark and Finland also apply this “Nordic Model”, but in both jurisdictions public companies can choose to adopt a German-type two-tier structure instead.

Similarly, Italian law offers not two but, three separate forms of organisation for corporate boards. For companies adopting the “traditional model”,29 the board of directors is accompanied by a “board of auditors”, which has only parts of the responsibilities that are typically associated with a supervisory board. Apart from the “traditional model”, Italian law also allows for the adoption of “typical” oneand two-tier board structures. Portugal adopts a very similar approach, also offering the choice between these three forms.30

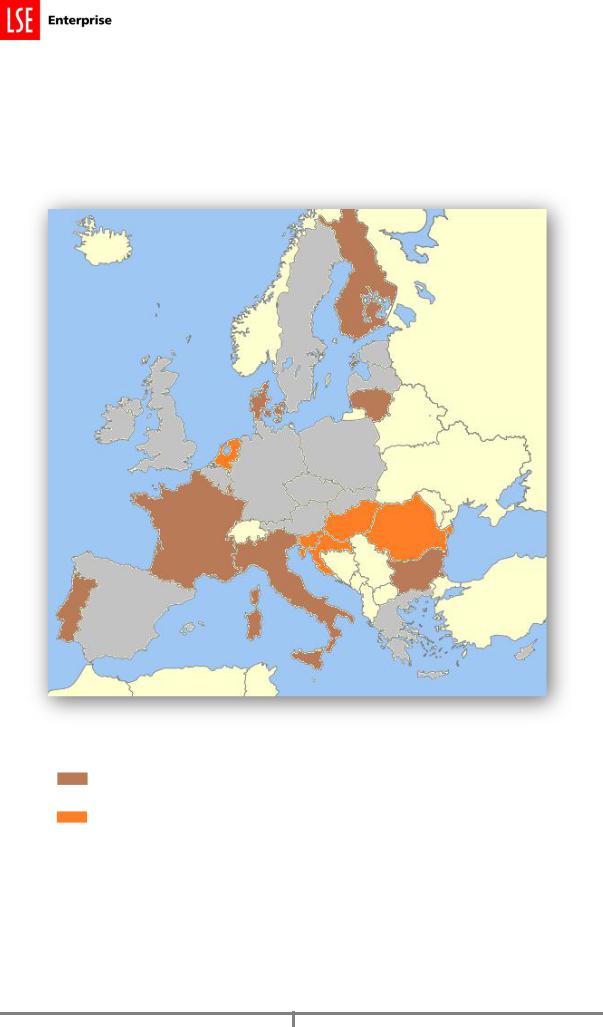

1.3 Mapping board structures II: Prevalent choices

It should be noted, however, that in most of the Member States allowing for choice between different board structures, and particularly in the Member States that introduced such choice relatively recently, only few companies make use of the flexibility the law offers. The table below summarises the prevalent choices made by public companies in Member States classified as “choice”-countries above.

24See e.g. H Eidenmüller, A Engert, and L Hornuf, ‘Incorporating under European Law: The Societas Europaea as a Vehicle for Legal Arbitrage’ (2009) 10 European Business Organization Law Review (EBOR) 1-33.

25In relation to the UK the argument can be (and has been) made that nothing in its national company law prohibits the adoption of a board structure that comes very close to the traditional two-tier board; see PL Davies “Board Structure in the UK and Germany: Convergence or Continuing Divergence?” (2001) 2 International and Comparative Corporate Law Journal 435. See also n 21 above. A similar argument can be made in relation to Cyprus and Ireland.

26See also D Johanson and K Østergren, ‘The Movement Toward Independent Directors on Boards: A Comparative Analysis of Sweden and the UK’ (2010) 18 Corporate Governance: An International Review 527, 530.

27See the Swedish report in the Annex; see also B Kristiansson, “Directors’ Remuneration in Listed Companies – Sweden”

(2008), (available at www.ecgi.org/remuneration/questionnaire/sweden_update_2008.pdf) 2.

28Rolf Dotevall, Bolagsledningens skadeståndsansvar (Norstedts Juridik 2008) p. 31.

29See the Italian report in Annex I. See also F Ghezzi and C Malberti, “The Two-Tier Model and the One-Tier Model of Corporate Governance in the Italian Reform of Corporate Law” (2008) 5 European Company and Financial Law Review

(ECFR) 1, 11.

30See Portuguese Report in Annex I, p 7-8.

7 Directors’ Duties and Liability in the EU

Based on our analysis of the real-life divisions between the different company organs, we decided to classify the system predominantly adopted by Italian and Portuguese companies as “one-tier”, although it is clearly possible to arrive at the opposite conclusion.

Map 1.3.b: Choices between one-tier and two-tier boards in countries providing a choice of different board structures

Legend |

Countries |

|

|

|

|

Predominant structure: |

BG, DK, FI, FR, IT, LT, LU, PT |

|

one-tier |

||

|

||

|

|

|

Predominant structure: |

HR, HU, NL, RO, SI |

|

two-tier |

||

|

||

|

|

1.4 Mapping board structures III: The roles of employee representatives

The table below summarises our findings regarding the roles of employee representatives on the board of (large) public limited companies throughout the European Union.

8 Directors’ Duties and Liability in the EU

Table 2.3.a: Employee participation in Europe

|

|

employee participation |

|

|

|

|

|

|

(if mandatory, board- |

|

|

|

|

|

|

level and independent |

|

|

|

|

|

|

of current/former state |

|

|

|

|

|

Country |

ownership) |

|

|

Details |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Austria |

Yes |

|

|

employees appoint one third of the members of the |

|

|

|

|

supervisory board |

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Belgium |

No |

|

|

Only applies in certain state-controlled companies |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Bulgaria |

No |

|

- |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Croatia |

Yes |

|

|

One member of the supervisory board |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Cyprus |

No |

|

- |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

In companies with at least 50 employees, employees |

|

|

Czech Republic |

Yes |

|

|

appoint one third of the members of the supervisory |

|

|

|

|

|

|

board |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Two members of the board when adopting the |

|

|

Denmark |

Yes |

|

|

“Nordic Model” of corporate governance |

|

|

|

|

Up to a third of the members of the supervisory board |

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

in companies adopting the two-tier model |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Estonia |

No |

|

- |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Finland |

Yes |

|

|

Employee participation subject to negotiation |

|

|

|

|

between company and employees |

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Only in state-owned or certain privatised companies |

|

|

France |

No |

|

|

For all other companies, employee participation is |

|

|

|

|

|

|

voluntary and depends on agreement with employees |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Between one third and half of the supervisory board |

|

|

|

|

|

|

seats are allocated to employees (one third for |

|

|

|

|

|

|

companies with more than 500 and up to 2,000 |

|

|

Germany |

Yes |

|

|

employees; one half for companies with more than |

|

|

|

|

2,000 employees) |

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

In companies with more than 2,000 employees, trade |

|

|

|

|

|

|

unions may also nominate representatives to the |

|

|

|

|

|

|

board |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Greece |

No |

|

|

Only in state-owned companies |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Hungary |

Yes |

|

|

one third of members of supervisory board, provided |

|

|

|

|

that company has more than 200 employees |

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Ireland |

No |

|

- |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Italy |

No |

|

- |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Latvia |

No |

|

- |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Lithuania |

No |

|

- |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

In companies with more than 1000 employees, one |

|

|

Luxembourg |

Yes |

|

|

third of the board members are employee |

|

|

|

|

|

|

representatives |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Malta |

No |

|

- |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Works council has nomination rights for up to a third |

|

|

|

|

|

|

of the board seats, but may not nominate employees |

|

|

Netherlands |

Nomination only |

|

|

of the company. The board members nominated by |

|

|

|

|

|

|

the employees still have to be elected by the |

|

|

|

|

|

|

shareholders. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

9 |

|

Directors’ Duties and Liability in the EU |

|

|

employee participation |

|

|

|

(if mandatory, board- |

|

|

|

level and independent |

|

|

|

of current/former state |

|

|

Country |

ownership) |

Details |

|

|

|

|

|

Poland |

No |

Only for (formerly) state-owned companies |

|

|

|

|

|

Portugal |

No |

- |

|

|

|

|

|

Romania |

No |

- |

|

|

|

|

|

Slovakia |

Yes |

One third of supervisory board members in |

|

companies with more than 50 employees |

|||

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

One third of supervisory board members (two-tier |

|

Slovenia |

Yes |

structure) |

|

One to three members, depending on board size |

|||

|

|

||

|

|

(one-tier structure) |

|

|

|

|

|

Spain |

No |

Only in state-owned companies |

|

|

|

|

|

Sweden |

Yes |

Two to three members of the board |

|

|

|

|

|

United Kingdom |

No |

- |

|

|

|

|

10 Directors’ Duties and Liability in the EU