мошонка, мочевой пузырь уретра

.pdf

162 ULTRASOUND: THE REQUISITES

A B

C

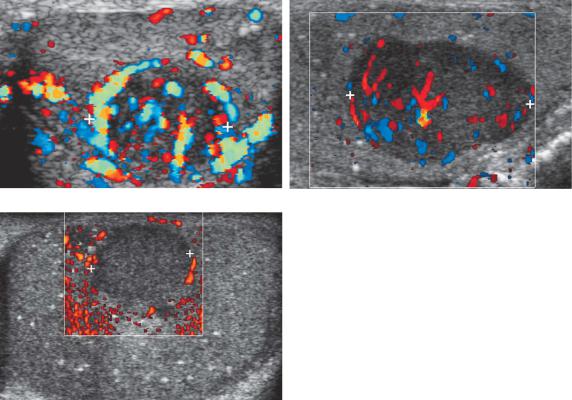

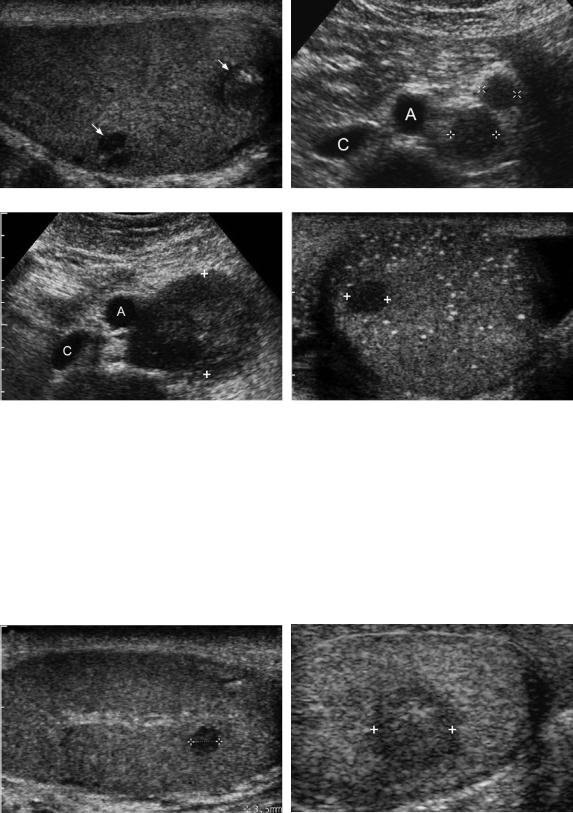

majority of germ cell tumors will have detectable internal vascularity on color Doppler imaging and some will be hypervascular (Fig. 6-19). When a lesion suspected to represent a germ cell tumor is detected in the testis, it is useful to scan the retroperitoneum near the level of the kidneys to look for nodal metastasis (Fig. 6-20A and B). When present, nodal metastases help to confirm that the testicular mass is a tumor and also upstage the tumor. Once the diagnosis is made, CT will be performed to more fully evaluate for metastatic disease. It is important to realize that this process also works in reverse. Whenever retroperitoneal adenopathy is detected in a young adult male, occult testicular tumors should be considered and a scan of the testes should be performed to look for an occult tumor (see Fig. 6-20C and D). If biopsies show that metastatic disease anywhere in the body is secondary to a germ cell tumor, sonography of the testes should also be performed. If a tumor is not identified with sonography, scrotal MRI should be considered.

Non-germ cell tumors account for 5% to 10% of testicular tumors. The most common are Leydig and Sertoli cell tumors (Fig. 6-21). Although the majority are benign, these stromal tumors can produce hormonal changes,

Figure 6-19 Testicular tumor vascularity in different patients. A, Longitudinal view of the testis shows a hypervascular teratocarcinoma (cursors). B, Longitudinal view shows a slightly hypervascular seminoma (cursors). C, Longitudinal view shows a seminoma (cursors) with no detectable internal blood flow. It is unusual for a solid tumor of this size to have no detectable blood flow.

and they are always removed because they cannot be distinguished from malignant germ cell tumors. They appear as solid masses, and their echogenicity ranges from hypoechoic to hyperechoic. Like germ cell tumors, internal vascularity is usually detectable on color Doppler analysis.

Epidermoid cysts are benign tumors similar to teratomas, but they contain only ectodermal derivatives. They appear as hypoechoic masses with a hyperechoic, calcified rim or multiple concentric internal laminations that simulate an onion slice (Fig. 6-22). Although these are virtually pathognomonic appearances, epidermoid cysts are typically enucleated while preserving the rest of the testis.

In addition to primary testicular tumors, the testes may be the site of metastatic disease. This usually appears as a focal testicular mass or masses with a variable echogenicity (Fig. 6-23). In elderly patients, metastatic disease is more common than primary germ cell tumors. The testes can also be involved with lymphoma and leukemia. Because chemotherapy does not cross a blood-testis barrier, the testes can serve as a sanctuary for lymphoma and leukemia when the patient’s disease is in remission elsewhere in the body. Lymphoma and

Lower Genitourinary |

163 |

A B

C D

Figure 6-20 Mixed germ cell tumor with lymph node metastasis. Longitudinal view of the testis (A) and transverse view of the upper abdomen (B) show two small heterogeneous solid masses in the testis (arrows). These are very suggestive of germ cell tumors, and a survey of the retroperitoneum should be performed for evaluation for possible lymph node metastasis. In this case, two enlarged periaortic nodes (cursors) were identified to the left of the aorta (A). The inferior vena cava (C) is also identified. Transverse view of the upper abdomen (C) and transverse view of the left testis (D) in a different patient who presented with back pain show a large retroperitoneal mass (cursors) deviating the aorta (A) anteriorly. The inferior vena cava (C) is also identified. Detection of retroperitoneal adenopathy in a young adult male should raise suspicion for a testicular tumor. In this case, subsequent scans of the testis confirmed the presence of a small solid germ cell tumor (cursors) in a testis with diffuse microlithiasis.

A B

Figure 6-21 Leydig cell tumors in different patients. A, Longitudinal view of the testis shows a small 3.5-mm hypoechoic solid mass (cursors) adjacent to the mediastinum. This was detected incidentally. B, Longitudinal view shows a larger solid hypoechoic mass (cursors).

164 ULTRASOUND: THE REQUISITES

Epidermoid. Longitudinal view of the testis shows a bilobed solid lesion. The larger inferior component (arrow) has a thin rim of peripheral calcification and faint posterior acoustic shadowing. The superior component (arrowhead) shows an internal “onion peel” appearance.

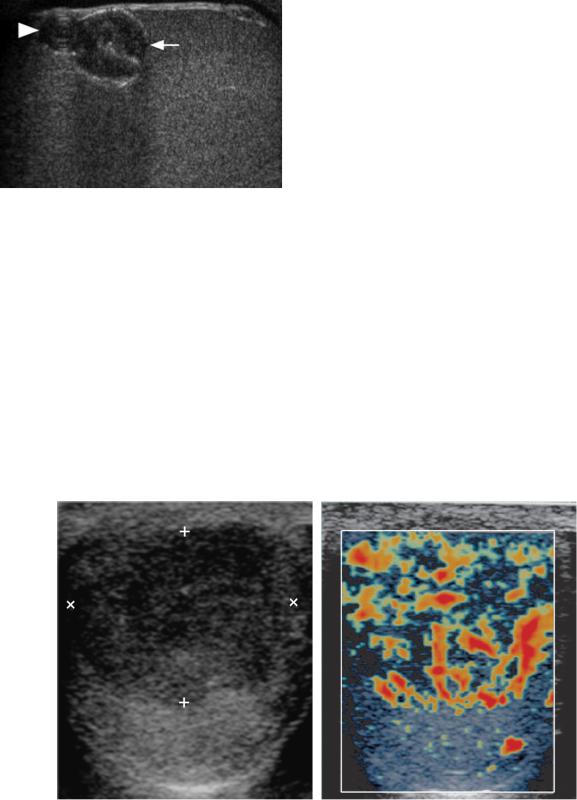

leukemia can both appear either as focal unilateral or bilateral hypoechoic masses or as diffuse testicular infiltration (Fig. 6-24). When the testes are diffusely infiltrated in a symmetric and bilateral manner, the decreased echogenicity may be difficult to appreciate. In such cases color Doppler imaging can be helpful in detecting an abnormality because the testis will be hypervascular. MRI can also be useful for further evaluation because the signal characteristics will be abnormal.

A

Sonography is highly sensitive (95% to 100%) in detecting testicular tumors. In fact, as mentioned earlier, an important role of sonography is to detect nonpalpable lesions in young adult men with metastatic disease from an unknown primary (see Fig. 6-20). The specificity of ultrasound varies depending on the referral patterns. There are numerous lesions that can simulate testis tumors (Box 6-3). These include infarcts, focal orchitis, focal fibrosis, hematomas, abscesses, sarcoid, tuberculosis, and adrenal rest tissue. In many cases the patient’s history is useful in suggesting the correct diagnosis. The physical examination is also very important because most palpable intratesticular lesions are tumors, and most of the nonpalpable lesions larger than 1 cm in diameter are not tumors. Lesions smaller than 1 cm may be nonpalpable tumors or benign lesions. Color Doppler also plays a role because many of the non-neoplastic lesions will not have any internal vascularity whereas most tumors will have detectable vascularity (Fig. 6-25).

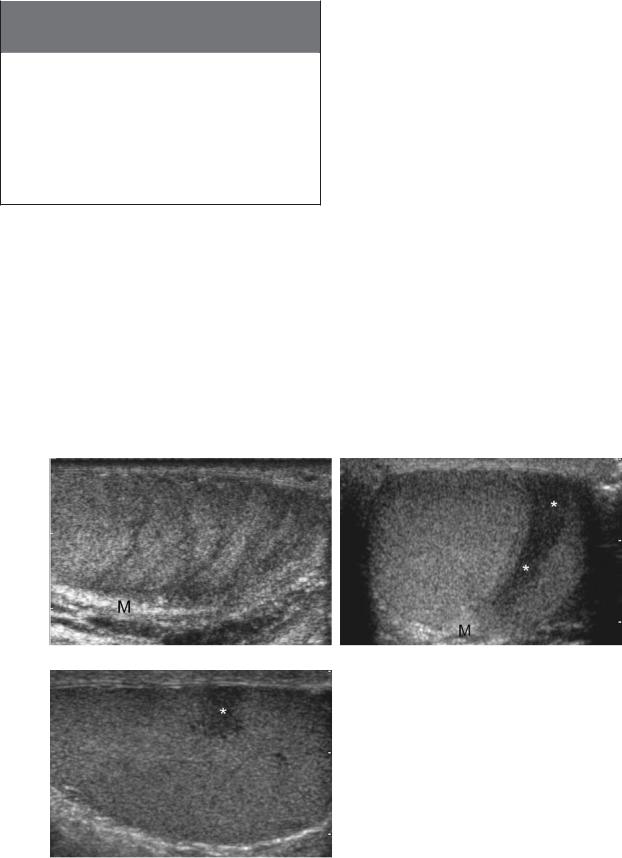

One relatively common abnormality that is easy to mistake for a tumor is testicular atrophy and fibrosis. In most patients these conditions can produce hypoechoic regions in the testis that are arranged in a linear pattern, producing a striated appearance to the testis that does not simulate a tumor (Fig. 6-26A). However, if these areas become more confluent, they can be misdiagnosed as tumors. This mistake can usually be avoided by scanning in multiple planes and noting the wedge shape of

B

Figure 6-23 Metastasis to the testis from a rhabdomyosarcoma. A, Gray-scale view of the testis shows a large solid hypoechoic mass (cursors) in the anterior aspect of the testis. B, Color Doppler view shows intense hypervascularity throughout this metastatic lesion.

Lower Genitourinary |

165 |

A B

Figure 6-24 Testicular lymphoma in different patients. A, Longitudinal view of the testis shows a solid homogeneous hypoechoic mass (cursors). B and C, Longitudinal gray-scale (B) and power Doppler (C) views in another patient show a slightly heterogeneous large solid mass (cursors) that shows intense hypervascularity on the power Doppler view.

C

A B

Figure 6-25 Testicular hematoma in different patients. A, Longitudinal view of the testis shows a slightly heterogeneous solid-appearing mass (cursors). This is nonspecific appearing and could be mistaken for a testicular tumor. B, Color Doppler view shows a heterogeneous predominately hypoechoic solid-appearing mass (cursors) with no detectable internal blood flow. In a posttraumatic patient, lack of detectable blood flow in a lesion such as this should suggest a testicular hematoma rather than a testicular tumor. Follow-up scans confirmed slow resolution of this lesion.

166 ULTRASOUND: THE REQUISITES

Box 6-3 Testicular Lesions Mimicking

Tumors

Focal orchitis

Focal atrophy/fibrosis

Infarcts

Abscess

Hematoma

Contusion

Sarcoid

Tuberculosis

Adrenal rest tissue

the abnormality and the way it radiates from the mediastinum (see Fig. 6-26B and C).

Testicular microlithiasis is a condition in which laminated concretions form in the lumen of the seminiferous tubules. On sonography they appear as tiny, nonshadowing, bright reflectors in the testicular parenchyma (Fig. 6-27). Classic testicular microlithiasis is defined as five or more microliths seen on at least one image of the testis. Microlithiasis with fewer than five microliths on all

A

images is referred to as limited testicular microlithiasis. Microlithiasis has been reported to occur in association with numerous conditions, the most important of which is testicular tumors. Approximately 10% of patients with microlithiasis will have a testicular germ cell tumor detected sonographically at the time of their initial ultrasound examination (Fig. 6-28). Several case reports suggest that patients who initially present with isolated testicular microlithiasis (i.e., testicular microlithiasis with no tumor) may be predisposed to develop tumors in the future. However, longitudinal data in larger groups of patients suggest that the risk, if real, is probably quite low. Original recommendations for patients with classic testicular microlithiasis were to have yearly ultrasound examinations. However, the yield of annual sonographic screening is so low that it is probably more realistic to perform regular self-examinations and annual physical examinations.

When a patient initially presents with a testicular tumor in one testis and has microlithiasis in the contralateral testis, the risk of intratubular germ cell neoplasia (the equivalent of carcinoma in situ of the testis) developing in the contralateral testis is definitely increased. Therefore, a biopsy of the contralateral testis is necessary to obtain tissue for histologic study. This is

B

Figure 6-26 Focal testicular atrophy/fibrosis. A, Longitudinal view of the testis shows hypoechoic striations in the testicular parenchyma radiating toward the mediastinum (M). B and C, Transverse (B) and longitudinal (C) views in another patient show a confluent area of atrophy (*) again radiating toward the mediastinum (M). On the transverse view the typical geometry of the lesion is seen. However, on the longitudinal view this lesion could be mistaken for a testicular neoplasm.

C

Lower Genitourinary |

167 |

A B

Figure 6-27 Testicular microlithiasis in different patients. A, Transverse view of both testes shows scattered bilateral small bright reflectors without acoustic shadowing. Because there are more than five detectable microliths in both testes, this meets the definition for bilateral classic microlithiasis. B, Transverse view shows three microliths in the testis. This is classified as limited microlithiasis.

usually done at the time orchiectomy is performed for removal of the ipsilateral tumor (see Fig. 6-28).

Calcification can also develop on the tunica albuginea of the testis and can present as a palpable mass. It is referred to as a plaque of the tunica and it usually occurs due to previous episodes of trauma or infection. When it is calcified it can be identified readily with sonography (Fig. 6-29A and B). Noncalcified plaques appear as thickening of the tunica but are much harder to see with sonography (see Fig. 6-29C).

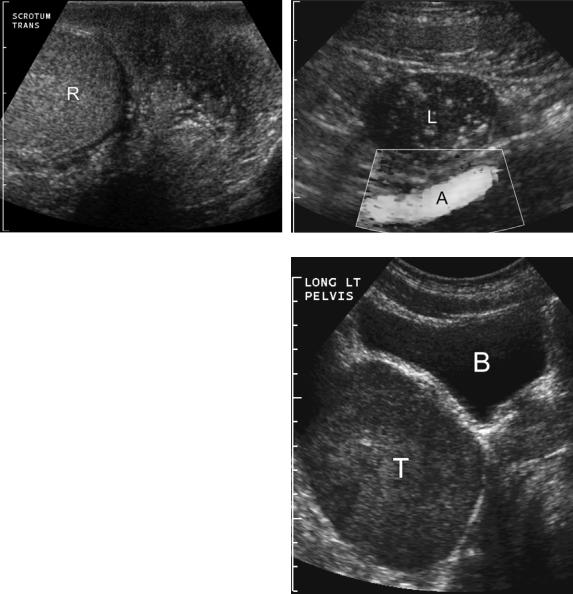

Another condition that is associated with testicular tumors is undescended testes. Approximately 80% of undescended testes are located within the inguinal canal and are easily visualized with sonography (Fig. 6-30A).

Intra-abdominal testes occur in the retroperitoneum from the level of the kidneys to the internal inguinal ring (see Fig. 6-30B). The risk of germ cell tumors is as much as 40 times greater than the general population, and the risk is even higher for intra-abdominal testes (Fig. 6-31). The risk of cancer is eliminated if the testis is surgically relocated to the scrotum prior to age 5. Between ages 5 and 10, orchiopexy has a diminishing effect on the rate of cancer. After age 10, orchiectomy is usually performed.

In addition to evaluating scrotal masses, ultrasound is helpful in the work-up of patients with acute scrotal pain and swelling. In the adult patient population, this primarily involves differentiating testicular torsion from

A B

Figure 6-28 Microlithiasis associated with a testicular tumor. A, Longitudinal view of the symptomatic testis shows a hypoechoic mass in the lower pole due to a germ cell tumor. Classic microlithiasis is seen in the upper pole of the testis. B, Longitudinal view of the contralateral testis shows classic microlithiasis here as well. At the time of orchiectomy, this contralateral testis was sampled and intratubular germ cell neoplasia was detected.

168 ULTRASOUND: THE REQUISITES

A B C

Figure 6-29 Fibrous plaques in different patients. A, Transverse view of the testis shows a small calcified plaque (arrow) of the tunica albuginea. B, Transverse view shows a small calcified plaque (arrow) of the tunica vaginalis of the scrotal wall. C, Transverse view shows a noncalcified plaque (arrow) of the tunica albuginea that manifests as a focal area of hyperechoic thickening of the tunica.

A B

C D

Figure 6-30 Undescended testes. A and B, Longitudinal views of the normal (A) testis and undescended (B) show that the undescended testis (cursors) that is located in the inguinal canal is smaller and has a more elongated appearance. It also has significantly thicker overlying tissues than the normal intrascrotal testis. C and D, Longitudinal view of the normal testis (C) and transverse view of the undescended testis (D) in another patient show the right external iliac artery (A) and vein (V) and the adjacent intrapelvic undescended right testis (cursors).

Lower Genitourinary |

169 |

A B

Figure 6-31 Undescended testis and tumor. A and B, Views of the scrotum (A) and pelvis (B) show a normal right testis (R) in the scrotum but an empty left scrotal sac. On the pelvic view, a hypoechoic undescended left testis (L) containing diffuse classic microlithiasis is also identified anterior to the external iliac artery (A). Orchiectomy in this case confirmed a left testicular germ cell tumor. C, Longitudinal view of the left pelvis in a different patient shows a large intrapelvic testis (T) located posterior to the urinary bladder (B). This was pathologically confirmed to be a germ cell tumor in an undescended testis.

C

inflammatory conditions such as epididymitis. Testicular torsion occurs as the result of the faulty attachment of the testis to the scrotal wall. The most common anatomic anomaly producing this faulty attachment is the bell-clapper deformity. It consists of a tunica vaginalis that completely surrounds the testis, causing the testis to be attached only to the spermatic cord and otherwise freely suspended in the scrotal sac like the clapper in a bell. The first hemodynamic consequence of testicular torsion is venous obstruction, followed rapidly by obstruction of arterial inflow and testicular ischemia. The viability of the testis depends on the duration of the torsion as well as the number of twists of the spermatic cord. Infarction can occur as soon as 4 hours after

the appearance of symptoms. However, if the degree of torsion is low (180 to 360 degrees), the testes can remain viable for more than 24 hours. In general, urologists try to operate before the symptoms have lasted for 6 hours.

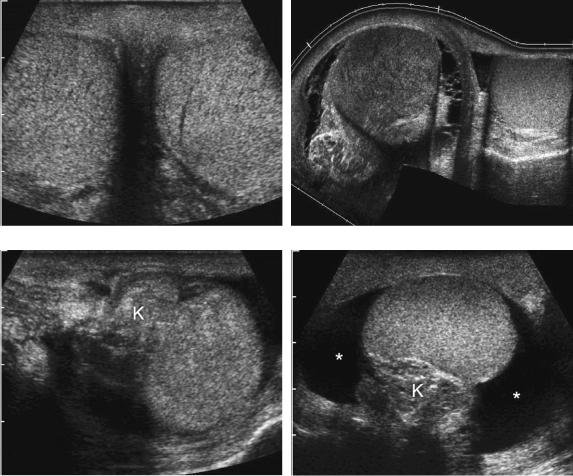

Gray scale sonography is not very valuable in diagnosing torsion because there may be no abnormalities (Fig. 6-32A). Nonspecific abnormalities that sometimes occur include decreased testicular echogenicity, testicular swelling, and reactive hydroceles (see Fig. 6-32B). A torsion knot due to the twisted spermatic cord is occasionally seen superior to the testis (see Fig. 6-32C). In rare instances, there is enough of a hydrocele so that it is possible to identify a bell clapper deformity (see Fig. 6-32D).

170 ULTRASOUND: THE REQUISITES

A B

C D

Figure 6-32 Gray-scale appearance of testicular torsion in different patients. A, Transverse view shows normal symmetric-appearing right and left testes. In this case the left testis was torsed. B, Extended field of view scan in a patient with right testicular torsion shows an enlarged hypoechoic right testis with a reactive hydrocele. The left testis is normal. C, Longitudinal view shows a torsion knot (K) in the spermatic cord located superior to the testis. D, Longitudinal view shows the torsion knot (K), posterior to the testis. A reactive hydrocele (*) is also identified. The acute angle between the hydrocele and the testis in all scanning planes indicated lack of attachment of the testis to the scrotal wall consistent with a bell clapper deformity.

Although gray-scale sonography is not good at identifying torsion in most patients, it can provide useful information about testicular viability. If the testis is normal on grayscale analysis, then it is very likely viable regardless of the duration of symptoms. If the testis is hypoechoic or inhomogeneous, it is very likely to be infarcted and nonviable.

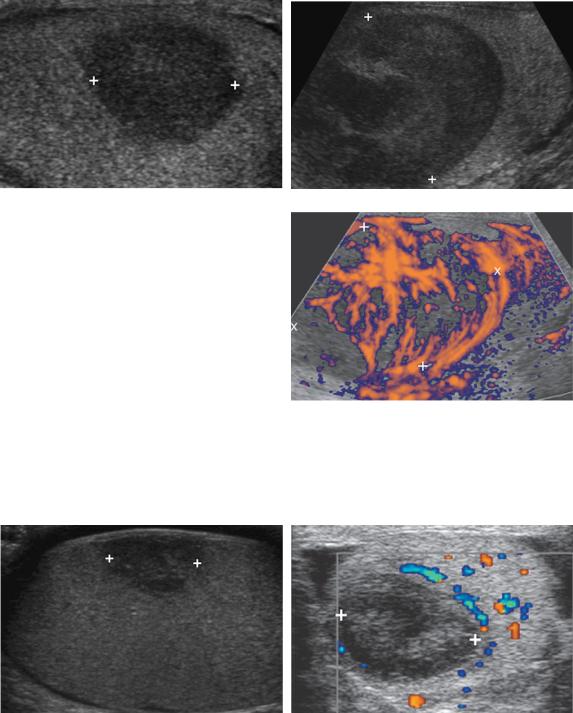

Fortunately color Doppler imaging is an effective way to detect testicular ischemia because it can show absent (Fig. 6-33A and B) or asymmetrically decreased testicular vascularity (see Fig. 6-33C). In prolonged torsion, there is an inflammatory reaction that develops in the soft tissue around the infarcted testis. This produces a hyperemic scrotal wall (see Fig. 6-33D). It is also an effective way of documenting the success or failure of manual

detorsion (see Fig. 6-33E and F). In adults, color Doppler analysis is better than scintigraphy in the diagnosis of testicular torsion. Given its speed, lower cost, lack of radiation, and better depiction of scrotal morphology, color Doppler imaging is the preferred way to evaluate these patients.

Although color Doppler imaging is quite good at evaluating patients with suspected testicular torsion, false-positive and false-negative results can occur. A false-positive finding means that the patient will undergo surgery, which he would have anyway if the ultrasound evaluation had not been performed. False-negative findings are more of a problem because most of these patients will then go on to suffer infarction of the testis.

Lower Genitourinary |

171 |

A B C

D E F

Figure 6-33 Color Doppler appearance of testicular torsion in different patients. A and B, Transverse views of a torsed testis (A) and the normal contralateral testis (B) shows no detectable blood flow in the torsed testis and readily detectable blood flow in the contralateral normal testis. C, Transverse view shows detectable but diminished blood flow in the testis. D, Transverse view shows a hypoechoic, heterogeneous testis with no detectable blood flow and increased flow in the wall of the scrotum. E and F, Color and pulse Doppler views of a torsed testis before (E) and after (F) manual detorsion. Note the detectable but diminished flow before manual detorsion and the reactive hyperemia immediately after manual detorsion.

False-negative findings can occur when the torsion is intermittent, is low grade, or spontaneously resolves. No technique that relies on blood flow determinations can establish the diagnosis if the blood flow is not decreased when the examination is performed.

Scrotal inflammatory disease usually involves the epididymis initially and spreads from there to the testis, scrotal sac, or scrotal wall. The hallmark of epididymitis on gray-scale studies is enlargement and decreased echogenicity of the epididymis (Fig. 6-34). Involvement of the epididymis may be diffuse but also

is frequently focal. Therefore, it is important to scan the entire epididymis in patients with suspected epididymitis. With advanced epididymitis, small abscesses are occasionally seen as complex hypoechoic collections in the epididymis (see Fig. 6-34E and F). Color Doppler imaging is valuable when the grayscale findings are equivocal or normal because it can detect inflammatory hyperemia as increased epididymal vascularity.

Orchitis usually occurs in conjunction with epididymitis. Isolated orchitis is less common and generally is