Encyclopedia of Sociology Vol

.5.pdf

TIME SERIES ANALYSIS

ters. However, this is an aesthetic yardstick that may have nothing to with the substantive story of interest.

USES OF ARIMA MODELS IN SOCIOLOGY

It should be clear that ARIMA models are not especially rich from a substantive point of view. They are essentially univariate descriptive devices that do not lend themselves readily to sociological problems. However, ARIMA models rarely are used merely as descriptive devices (see, however, Gottman 1981). In other social science disciplines, especially economics, ARIMA models often are used for forecasting (Granger and Newbold 1986). Klepinger and Weiss (1985) provide a rare sociological example.

More relevant for sociology is the fact that ARIMA models sometimes are used to remove ‘‘nuisance’’ temporal dependence that may be obstructing the proper study of ‘‘important’’ temporal dependence. In the simplest case, ARIMA models can be appended to regression models to adjust for serially correlated residuals ( Judge et al. 1985, chap. 8). In other words, the regression model captures the nonstationary substantive story of interest, and the time series model is used to ‘‘mop up.’’ Probably more interesting is the extension of ARIMA models to include one or more binary explanatory variables or one or more additional time series. Nonstationarity is now built into the time series model rather than differenced away.

Intervention Analysis. When the goal is to explore how a time series changes after the occurrence of a discrete event, the research design is called an interrupted time series (Cook and Campbell 1979). The relevant statistical procedures are called ‘‘intervention analysis’’ (Box and Tiao 1975). Basically, one adds a discrete ‘‘transfer function’’ to the ARIMA model to capture how the discrete event (or events) affects the time series. Transfer functions take the general form shown in equation (1):

(1 − δ1B− −δ1Br)yt=(ω0−ω1B− −ωsBs)xt−b.

If both sides of equation (1) are divided by the left-hand side polynomial, the ratio of the two polynomials in B on the right-hand side is called a transfer function. In the form shown in equation (1), r is the order of the polynomial for the ‘‘dependent variable’’ (yt), s is the order of the polyno-

mial for the discrete ‘‘independent variable’’ (xt), and b is the lag between when the independent ‘‘switches’’ from 0 to 1 and when its impact is observed. For example, if r equals 1, s equals 0, and b equals 0, the transfer function becomes ω0/1-δ1. Transfer functions can represent a large number of effects, depending on the orders of the two polynomials and on whether the discrete event is coded as an impulse or a step. (In the impulse form, the independent variable is coded over time as 0,0, . . . 0,1,0,0, . . . ,0. In the step form, the independent variable is coded over time as 0,0, . . .

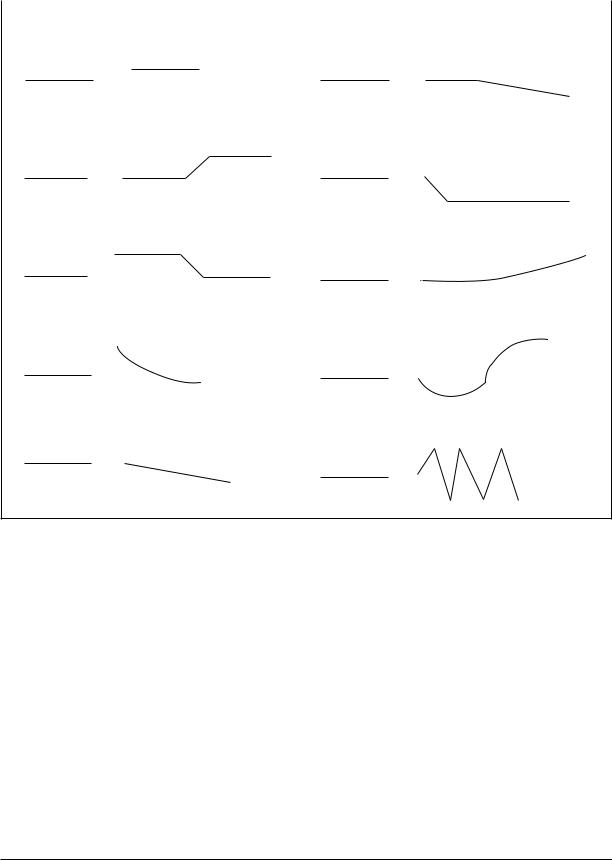

1,1 . . . 1. The zeros represent the absence of the intervention, while the ones represent the presence of the intervention. That is, there is a switch from 0 to 1 when the intervention is turned on and a switch from 1 to 0 when the intervention is turned off.) A selection of effects represented by transfer functions is shown in Figure 6.

In practice, one may proceed by using the time series data before the intervention to determine the model specification for the ARIMA component, much as was discussed above. The specification for the transfer function in the discrete case is more ad hoc. Theory certainly helps, but one approach is to regress the time series on the binary intervention variable at a moderate number of lags (e.g., simultaneously for lags of 0 periods to 10 periods). The regression coefficients associated with each of the lagged values of the intervention will roughly trace out the shape of the time path of the response. From this, a very small number of plausible transfer functions can be selected for testing.

In a sociological example, Loftin et al. (1983) estimated the impact of Michigan’s Felony Firearm Statute on violent crime. The law imposed a two-year mandatory add-on sentence for defendants convicted of possession of a firearm during the commission of a felony. Several different crime time series (e.g., the number of homicides per month) were explored under the hypothesis that the crime rates for offenses involving guns would drop after the law was implemented. ARIMA models were employed, coupled with a variety of transfer functions. Overall, the intervention apparently had no impact.

3151