- •От автора

- •Glimpses of British History

- •Early Britain

- •The House of Normandy

- •Medieval England

- •Tudor England

- •The Stuarts

- •Georgian Britain

- •Victorian Britain

- •Edwardian Britain

- •Britain and the two World Wars

- •Britain after World War II

- •Modern Britain

- •Modern British Monarchy

- •British Parliament

- •The House of Lords

- •The House of Commons

- •Government

- •Local Government

- •The Legal System

- •Historic Country Houses and British Heritage

- •Glossary

- •British History

- •Modern Britain

- •The Monarchy

- •British Parliament

- •Elections

- •Government

- •Local Government

- •The Legal System

- •Historic Country Houses

- •Architecture

- •Key to some phonetic symbols:

- •Bibliography

- •Dictionaries Used

А. Г. Минченков. «Glimpses of Britain. Учебное пособие»

The Stuarts

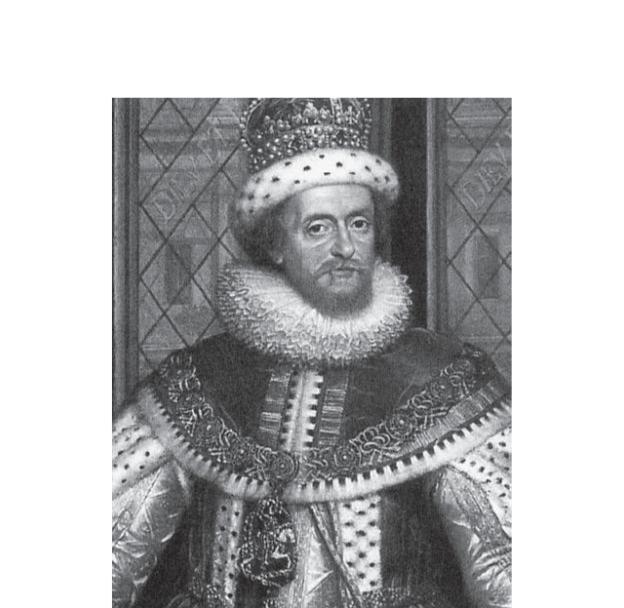

On her deathbed Elizabeth nominated James VI of Scotland, son of Mary Queen of Scots, as her successor. When she died he became James I of England (1603–1625) starting the new Stuart dynasty. Robert Cecil, Elizabeth’s chief minister during the last years of her reign, ensured a smooth succession. What the country desperately needed at the beginning of a new century was a reforming monarch. What it got was one wishing to enjoy the many comforts which had come to him after many years of spartan deprivation spent in the backward and poverty-stricken northern kingdom. Having grown up in Scotland, where the nobility was powerful and Parliament weak, James was ill-equipped to deal with the realities of 17th century England. He passionately believed in the theory of government known as the Divine Right of kings, had written a treatise on it to support royal absolutism and had effectively practiced his theory in Scotland. James was scholarly and intelligent in a pedantic way. A theorist, he understood books much better than he did his subjects and was called ‘the wisest fool in Christendom’ by a French contemporary.

There were several problems not resolved by the Tudor monarchs and inherited by James: inflation, the rising influence of the gentry, lawyers jealously guarding the common law against royal encroachments and Puritan dissatisfaction with the Church of England. The biggest problem James inherited was how to pay for the government. Running the kingdom was becoming more and more expensive (salaries of officials, costs of the army, navy, law courts, treasury and royal court). Besides, the king was still expected to live ‘of his own’, asking for money from Parliament only to meet the expenses of war. The way to solve the problem was for Parliament to recognize the need for regular taxation in time of peace. The second way was for the king to get rid of Parliament, something which was happening all over the rest of Europe at the time, and develop to the full the royal Divine Right to impose various taxes and dues. But the new dynasty brought a progressive erosion of trust between the monarchy and the people, which can be attributed to the characters of the first two Stuart kings. James had a deep dislike of public appearances and crowds in general, so that the contrast with the Tudors, who had been brilliant actors on the political stage, could not have been greater. Moreover, it was soon discovered that James’s ‘natural disposition’ led him away from what many regarded as his kingly duties. Elizabeth had made herself central to decision-making on virtually every level, playing her counsellors and courtiers off against each other as though they were suitors for her affections. This meant that, no matter how annoying her counsellors may have found her, Elizabeth was always present, always the centre of their attention. But the new king was more often away from court altogether, in the country with his horses and his hounds. It has been calculated that throughout his entire reign in England, James spent about half his time either at his hunting lodges or on progress, and when at the lodges, his household comprised only a few people. James may have imagined that he had struck a perfect bargain: the Privy Council would be given a free hand, and he would be allowed to regain his health. But in practice, things didn’t work out so simply. It soon became apparent that the Council wasn’t confident of its power to bypass the king and was forced constantly to attempt to win the king’s attention while he was on hunting trips, which wasn’t an easy thing to do. Complaints about James’s hunting were almost always complaints about James’s style of government, namely, his failure to govern effectively because of his physical absence from court. His new favourites were those who distinguished themselves at the hunt, not at court or in government. While James stated both in his writings and public speeches that kings were God’s lieutenants on earth, referring to the Divine Right of kings, the court became a byword for extravagance and corruption as the king showered offices, titles, lands and money on his politically inept favourites. All Parliament saw was money seemingly wasted, and it was difficult to persuade it to vote regular taxation. With the rise of favourites the king’s councillors

38

А. Г. Минченков. «Glimpses of Britain. Учебное пособие»

lost their influence on parliamentary legislation since they no longer introduced legislation, as they had done in the days of Elizabeth.

James I

James was fortunate in inheriting Robert Cecil, William Cecil’s son, whom he ennobled as Lord Salisbury. Salisbury set about the only major attempt to put the government’s finances in good order via Parliament. But Parliament refused to come to terms with the reality of paying for running the government. The developing conflict between the king and his Parliament centred on ‘parliamentary privilege’ versus ‘royal prerogative’. At the beginning of the reign few established rules existed that clearly indicated the rights and privileges of Parliament. The Commons, however, soon asserted its undefined privileges as inalienable rights and developed a political doctrine to back its position. The attack of the Commons on royal prerogatives was supported by the common law courts which had formerly been allies of the Crown. The Commons asserted that Parliamentary privileges had an ancient, and not necessarily royal, origin, that the king was under law and that the courts were independent of the Crown. James, however, wouldn’t yield his prerogatives and only gave in on the matter of royal monopolies because he knew when to compromise.

Salisbury died in 1612, and the same year the king’s eldest son Henry died too. After these two deaths there was a steady lurch downhill. No one of Salisbury’s caliber replaced him. For most of the rest of the reign James ruled without Parliament, obtaining revenue by every possible means at his disposal from forced loans to the selling of titles. Quite soon the king became dominated by George Villiers, a poor son of a Leicestershire gentleman. His rise was meteoric: Viscount Villiers

39

А. Г. Минченков. «Glimpses of Britain. Учебное пособие»

in 1616, Earl of Buckingham in 1617, Marquis in 1618 and, finally, Duke in 1623. Buckingham was more dangerous than his predecessors, for he combined political ambitions with political inaptitude. Like James, he wasn’t a reformer, but knew just how to keep the existing system creaking along. Buckingham dominated a whole decade, in fact uniting the reign of James and that of his heir, until he was assassinated in 1628.

James, like Elizabeth, maintained the comprehensive nature of the national church and during much of his reign Puritanism and Anglicanism existed side by side. The Puritan life was one of the faith in action, with a strong emphasis on public morality and order. The focus of Anglicanism was different for it retained many practices and beliefs from the medieval Catholic Church. James found plenty to please him in the top ranks of the Anglican Church. These men were scholars, intellectuals and writers: John Whitgift, the Archbishop of Canterbury; Richard Bancroft, then Bishop of London; Thomas Bilson, Bishop of Winchester. James was in his element. He had his bishops, who accepted the Divine Right of kings. Every church service exalted the king, in abstract and in person. The Church of England had rituals and ceremonies that had great attraction for James. In 1603 some 800 Puritan preachers presented the Millenary Petition to the king in which they requested a simpler ritual, a greater emphasis on preaching and the abolition of certain ceremonies. They also requested an English translation of the Bible. The king’s initial reaction to the Petition was rather gracious. It was only when he embarked on a series of conferences, both formal and informal, with the English bishops that his attitude began to change. As the Anglicans played on the analogy between English Puritanism and Scottish Presbyterianism (in fact there was a huge gulf between the Presbyterians and the Puritans) James began to move towards a more unsympathetic stance. Yet he was willing to entertain one of the ideas of the Petition – a conference between Anglicans and Puritans. It appealed to his notion of himself as an intellectual. The result was the Hampton Court Conference (1604). It showed that the Anglicans found in their new king a learned and serious champion. Most of the Puritans’ requests weren’t granted and their suggestion to abolish the office of bishop indeed enraged the king. Yet there was a positive development – the king’s agreement to authorize a new version of the Bible. The result – the King James Bible or the King James Version – was proudly published in 1611 and stood the test of time. To many people the language provided by fifty-four men of varying doctrinal belief and political allegiance working in three separate locations between 1604 and 1611 is still the language of the Church of England.

James as a sovereign gave his name to the Jacobean age but, indeed, he was strangely indifferent to many of the phenomena that we now see as peculiarly Jacobean. England had entered the 17th century with immense promise. A new world was opening up for English adventurers and merchants, with exciting and exotic new territories. In 1607 England’s first permanent colony was established in Jamestown, Virginia and in 1620 English Puritans sailed on the Mayflower to Plymouth, New England. Modern science was being born through the insights of Francis Bacon and William Harvey, both of whom became personal servants to the king. English theatre was at its peak, with William Shakespeare one of James’s own acting company, the King’s Men. Inigo Jones brought the latest European taste to the king’s Banqueting House in Whitehall [51], the Queen’s House in Greenwich [52] and masques at court. But James seemed unimpressed. He mocked colonial exploration, fell asleep during England’s most celebrated plays, and showed little interest in scientific advances. The king’s energies would be devoted elsewhere, to old-style religious and dynastic politics. By contrast, his queen, Anna of Denmark, had a much more different life-style. She took over Greenwich Palace and then Somerset House in the Strand in London, which she renovated and renamed as Denmark House. By about 1607, the royal couple were rarely in residence together. The queen’s household quickly emerged as a court in its own

40

А. Г. Минченков. «Glimpses of Britain. Учебное пособие»

right. Anna patronized playwrights and poets, painters and designers. The queen and her ladies are also famous for popularizing masques. The first was staged in 1605 by Inigo Jones, the text being written by the poet and playwright Ben Jonson. Masques were court entertainments, expensive pieces of theatre whose appeal lay in the design of their sets and costumes, in their special effects, the music and dancing, and in the novelty of having royalty and nobility performing on stage. They were often filled with topical allusions and performed in classical and foreign settings. James’s standard reaction to being shown a masque was to yawn and have his glass refilled.

As for the Catholics, they basically went on as before in spite of the Gunpowder Plot (1605), when several Catholics headed by Guy Fawkes wanted to blow up the Lords and Commons and most of the royal family in one huge explosion. The conspiracy was betrayed and for a time Catholics were fined and imprisoned, but then the clouds blew over and there was a reversion to the norm. Peace with Spain (1604), and James’s passionate wish to act as a peacemaker in Europe by marrying one child to a Protestant and another to a Catholic, made things easier for them. In foreign affairs James was a pacifist and it was only in 1624, the last year of his reign, that he allowed himself to be involved in the Thirty Years’ War (1618–1648). Influenced by Buckingham, Charles, his heir, and Parliament he declared war on Spain.

James hoped for the union of England and Scotland, but Parliament was opposed to the idea and even refused free trade and English citizenship to the Scots. Except for removing the danger of border warfare and French influence in Scotland, the two countries remained separate nations with a common king for another century.

In Ireland, the English attempts to enforce the Anglican supremacy led to uprisings in Northern Ireland. The English government responded by seizing land in six northern counties and settling Scotch Presbyterians, Welsh and English in the area known as Ulster.

The Jacobean style of architecture often refers to houses built in the first part of the reign of James I, forming a transition between the Elizabethan and the pure Palladian style introduced by Inigo Jones. The Jacobean style adopted Palladian motifs in a free form communicated to England through German and Flemish carvers rather than directly from Italy. It is characterized by a more formal design; much use was made of columns and pilasters, round-arch arcades and flat roofs with openwork parapets. All these features can be seen in Hatfield House [48; 49]. Another fine example of a Jacobean house is Sudbury Hall (begun in 1613) [50], which has a two-storeyed classical centerpiece, a balustrade, dormers, and a cupola. An interesting feature of Sudbury Hall is the use of brick of two colours to make a diaper pattern.

The Jacobean style of architecture often refers to houses built in the first part of the reign of James I, forming a transition between the Elizabethan and the pure Palladian style introduced by Inigo Jones. The Jacobean style adopted Palladian motifs in a free form communicated to England through German and Flemish carvers rather than directly from Italy. It is characterized by a more formal design; much use was made of columns and pilasters, round-arch arcades and flat roofs with openwork parapets. All these features can be seen in Hatfield House [48; 49]. Another fine example of a Jacobean house is Sudbury Hall (begun in 1613) [50], which has a two-storeyed classical centerpiece, a balustrade, dormers, and a cupola. An interesting feature of Sudbury Hall is the use of brick of two colours to make a diaper pattern.

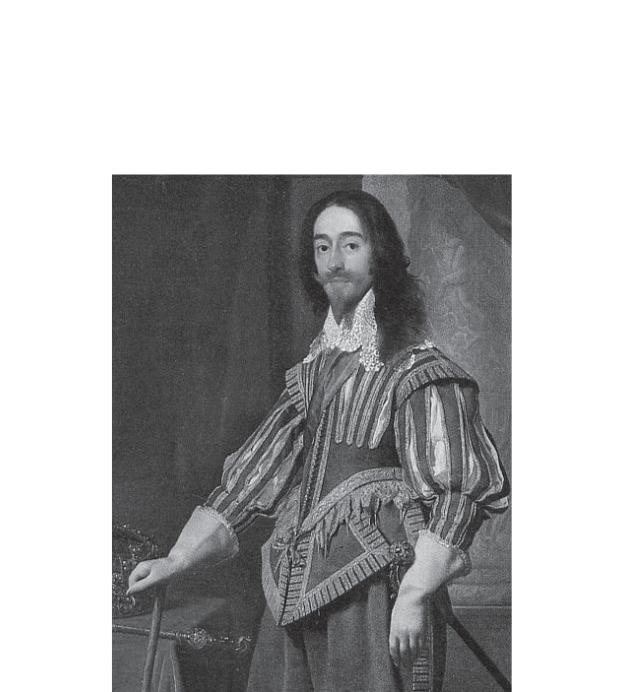

When James I died in 1625 he was succeeded by his son Charles. The twenty-five-year-old king was a great patron of the arts, a shy person, highly religious and an affectionate family man. He was more dignified and attractive than his father, but, like his father, he believed in the Divine Right of kings. For Charles I (1625–1649) the monarch was a sacred being set apart, something which was emphasized by his austere and reserved manner and his introduction of the rigid ceremonial at court. The latter became a closed world, from which he excluded those whose views didn’t coincide with his own. As a result, the monarchy was gradually cut off from popular support. Besides, in 1625 royal credit was truly exhausted. The Thirty Years’ War in which James had involved the country was still going on and England couldn’t afford it. So the pattern began of Parliaments refusing to pay for mishandled wars over the course of which they had no control. In 1626 the

41

А. Г. Минченков. «Glimpses of Britain. Учебное пособие»

crown jewels were pawned and, the following year, Charles made over to the City most of the remaining crown lands to pay off royal debts. This act represented the effective end of medieval kingship, for when the lands went the king had no longer anything ‘of his own’ by which to pay for government. The only way forward, if Parliament refused to cooperate, was to use the royal prerogative and raise taxes.

Once again Charles called Parliament, but it wanted government without paying for it. The Crown was in fact more forward-looking in its policies. After Buckingham was killed in 1628 Charles decided to rule without Parliament. He realized that as long as he avoided war he could do this. Thus in 1629 Charles embarked on a decade known as the years of Personal Rule. It was successful. The king made peace with both France and Spain and together with his queen, Henrietta Maria, he set out to make his court a model in terms of virtue and good order for the rest of the country to emulate. After the immoral court of his father, Charles’s was a monument to sobriety.

Peace brought commercial prosperity and, with it, income to the Crown through customs dues. Financially the king stretched his prerogative dues to their limit: he revived ancient forest laws, invented new monopolies, and invoked an old statute that required all landholders with an annual income of Ј40 to be knighted. A large fee was charged if they became knights and a huge fine if they refused. The tax arousing the greatest opposition was so-called ship money – a tax which seacoast towns had paid in earlier centuries to create a fleet and naval defences in times of danger (threatened invasion). People objected because England was at peace and Charles demanded the tax of inland as well as coastal counties.

The king had two able ministers – Thomas Wentworth (later the Earl of Strafford) and William Laud, Archbishop of Canterbury, the latter carried through the royal religious policy. Charles didn’t share his father’s stance on religion. He believed the Puritans had to be rooted out. The Church of England was for him the old pre-Reformation Catholic Church, purged of abuses and superstition. That position, which Elizabeth had shared but never enforced, now came into reality. Order, ceremony and the beauty of art were reintroduced into the churches: stained glass, crucifixes, candlesticks, bowing towards the altar and vestments. Charles I changed virtually all the bishops and senior clergy, appointing those who would carry through changes. Laud was tactless and pushed on relentlessly with the reformation, and the suppression of Puritanism. Members of Parliament were overwhelmingly Puritan, but without its meetings they had lost their mouthpiece.

On the surface the king’s long peace seemed like Arcadia. The fluidity of the social structure inherited from the Tudors continued, something which set England apart from mainland Europe where the aristocracy became a caste. In England the nobility paid taxes, married commoners and engaged in commercial investment. People could move socially upwards if they were clever, and by 1640 about 1/3 of the male population were literate.

Trouble began in Scotland which had an extreme Protestant tradition in the spirit of Calvin. Charles I decided to extend uniformity and order to Ireland and Scotland. In 1637 he issued a version of the English Prayer Book for use in Scotland. It was introduced without any consultation either with the Scottish Parliament or the church assembly. The result was riot and rebellion. The transformation of the Church of England under Laud signaled to the Scots that the age of Antichrist had indeed come. They took to arms and marched across the border. Everything the king had striven to achieve depended on avoiding war. And now it had come. Without Parliament Charles could only resort to calling the old medieval tenants-in-chief. But they were an ill-armed and ill-trained motley crew that disintegrated in the face of the Scots. In 1639 Charles was forced to buy time and signed the Treaty of Berwick. In the midst of the crisis he turned to Thomas Wentworth, now ennobled as Earl of Strafford. The latter advised calling Parliament.

The Short Parliament of 1640 assembled in an angry mood and refused to vote funds until it had discussed grievances. Within three weeks Charles dissolved Parliament (hence the name “short”) and made desperate attempts for funds and men to fight the Scots. Unlike his European

42

А. Г. Минченков. «Glimpses of Britain. Учебное пособие»

counterparts, the English king lacked both a trained and paid bureaucracy and a standing army and largely depended on the loyalty of his people and unpaid local officials. Charles’s attempts met with little success, the Scots invaded England with ease and forced Charles to terms which stipulated that they would stay in England and receive Ј850 daily from the king until a settlement was signed. To pay the bill Charles was forced to summon another Parliament in 1640 which turned out to be a Long Parliament.

Charles I

The Long Parliament was in general agreement in its efforts to curb the king’s prerogatives and abuse of power by parliamentary legislation. There was little thought of revolution or deposing the king. In the early months of its work the Long Parliament passed important acts including the Triennial Act demanding that Parliament should meet at least every three years; no dissolution of Parliament without its consent and no type of taxation without parliamentary consent. When the Puritan members proposed abolishing bishops and radically reforming the Church it alienated a considerable number of more conservative members. In the summer of 1641 the division was further widened by the news of a far-reaching rebellion in Ireland and the massacre of English and Scottish settlers in Ulster. Parliament wished to send over an army to crush the rebellion but didn’t want to place a large force under the control of the king. In the Grand Remonstrance passed by only eleven votes parliamentary approval was demanded of both the king’s advisers and the army officers. Instead of waiting and winning over a few more members, Charles committed a political

43

А. Г. Минченков. «Glimpses of Britain. Учебное пособие»

error by marching into the House of Commons with an armed guard to arrest five of its leading members; however, the members had been forewarned and had fled. Soon after this Charles rode north to raise an army and to show by force that he was king. His subjects gradually took sides and prepared for war. In June 1642 Parliament sent the king an ultimatum (the Nineteen Propositions) requiring that he should surrender virtually all his remaining prerogative powers. These demands indicated that any hope of compromise was past, and in August civil war began.

Geographically, the king’s supporters (Cavaliers) centred in the less populous areas of the north and west. His party included most of the nobility, many of the gentry, Roman Catholics and Anglicans. Parliament’s supporters (Roundheads) drew their major strength from the south and east of the country. In the first two years the Cavaliers were victorious because of the quality of their cavalry and leadership. But time favoured Parliament because of its control of the richer and more populous areas of the country and the backing of the navy. After Oliver Cromwell had taken over command of the parliamentary troops the New Model Army was created, which decisively defeated the Royalists at the Battle of Naseby (1645). By the end of 1646 the first Civil War had ended but the king’s dealings with the Scots brought on a short second Civil War that Cromwell’s forces won easily after routing the Scottish-Royalist army near Preston (1648). That left the army in control of the country. It promptly purged Parliament of some 140 members it disliked. The remaining 96 members – the Rump Parliament – took orders from the army. They appointed a court of commissioners to try the king for treason. As justice could be carried out only in the king’s name in the law courts, the court made up of the members of the Commons had no legal status. Charles never accepted the legality of this tribunal and refused to speak in his own defence. The verdict was never in doubt, for the army had decided upon the execution of the king. However, only fiftynine signatories could be found to sign the warrant for his execution. On 30 January 1649, Charles met his death with calmness and dignity, saying ‘I go from a corruptible to an incorruptible crown, where no disturbance can be’. For those who believed in the monarchy the execution was an act of blasphemy, the slaying of the Lord’s anointed. The scaffold was erected before Inigo Jones’s Whitehall Banqueting House, the setting of the masques in which Charles had appeared to his court as a deity. It was surrounded by soldiers as public unrest was feared.

The king’s departure from London at the beginning of the first Civil War marked the dissolution of the most civilized court in Europe. Charles I was the greatest patron of the arts ever to sit upon the throne. During his reign all the achievements of the Italian Renaissance reached England. That was due not only to the support of the king but to the genius of Inigo Jones, who was his adviser on matters connected with the arts and who was in charge of all royal building enterprises.

The king’s departure from London at the beginning of the first Civil War marked the dissolution of the most civilized court in Europe. Charles I was the greatest patron of the arts ever to sit upon the throne. During his reign all the achievements of the Italian Renaissance reached England. That was due not only to the support of the king but to the genius of Inigo Jones, who was his adviser on matters connected with the arts and who was in charge of all royal building enterprises.

Jones had begun his career in the previous reign. In 1613 he set out on a tour of Italy, and coming back to England in 1615 brought with him the architectural drawings of the two greatest Venetian Renaissance architects, Palladio and Scamozzi. In the same year he was made Surveyor General in control of the entire royal building programme. His first building was to be a revolution, the earliest Palladian villa ever erected in England, the Queen’s House, Greenwich. This was to be the ancestor of hundreds of country houses. The Queen’s House was followed by the new Banqueting House to replace the old one that had burnt to the ground. Completed in 1623, the new Banqueting House was a double cube modeled on an ancient Roman basilica and at the time must have created a sensation towering above the asymmetrical red-brick Tudor Whitehall Palace.

44

А. Г. Минченков. «Glimpses of Britain. Учебное пособие»

Charles I was never rich enough to build as he would have wished. Inigo Jones drew endless schemes for a vast new palace but it was never built. In many ways Jones was ahead of his time, for it was not until well into the 18th century that the classical ideas of Palladianism became truly widespread in England. Just a handful of great English country houses built between 1630 and 1660 are in the Palladian style. In the 1630s the 4th Earl of Pembroke commissioned Jones to remodel Wilton House in the new style [46; 47]. However, the Palladian designs by Inigo Jones were too closely associated with the court of Charles I to survive the turmoil of the civil war.

The execution of the king transformed England into a republic which few in England had foreseen or actually desired. Parliament was now free to set up whatever form of government it thought necessary. In February 1649 the monarchy and the House of Lords were abolished. In February a Council of State was set up, elected from the Commons, to govern the country. In May England was declared to be ‘a commonwealth and free state’ under God. What was lacking was a government which had a clear policy. In the spring of 1650 Parliament began to pass acts to create the society of the saints. The death penalty was introduced for fornication, adultery, swearing and blasphemy. The courts, however, never implemented it. Simple pleasures such as the Twelve Days of Christmas were forbidden. Parliament demanded that all adult males swear an oath of loyalty to the new regime. As a result all over England people refused and lost office, forming thereby a substantial group opposed to the new government. Another problem of the government was lack of money. All its funds were eaten up paying for the civil wars and the army. Everything that could be sold was sold: the cathedrals, royal palaces, the king’s fabulous art collection, what little remained of the crown lands, the lands of the dispossessed Royalists. All of this was made worse by a war with the Dutch. The army viewed the Parliament with distrust, as a body not advancing but actually holding back the rule of the saints. Finally Cromwell called on his troops and dissolved the Rump Parliament in April 1653. In its place he first established an assembly nominated by the officers of the army. Its task was to carry through the reforms necessary to ensure the godliness of the people. But in December the same year a group of moderates voted for the return of power back to the army and its leader, Cromwell. England’s brief experiment with republicanism came to an end. Cromwell assumed the role of Lord Protector. He was a deeply committed Puritan, but stood for religious tolerance. At the same time there was a struggle against immorality; Sunday sports were forbidden, alehouses and theatres closed, cock fighting and horse racing banned. The people were upset by these kill-joy policies, and even more resented the direct rule from Westminster, which was, in effect, army rule, by outsiders viewed as being of a low class. In his role of Lord Protector Cromwell experimented with various alternatives to monarchy, but each attempt failed over the incompatibility of a constitutional government and the ‘rule of the saints’ who considered themselves God’s elect, but were not politically elected by the nation. Still, Cromwell’s leadership saved England from the grim prospects of either anarchy or tyranny.

In 1658 Cromwell died. His son Richard became Lord Protector, but he lacked his father’s energy and feeling for power; worse, he wasn’t popular with the army. Army commanders defied Richard and grasped for power, while royalist and republican uprisings also took place. Finally General Monck, who headed the army in Scotland, marched south to support civilian rule. In March 1660 the Long Parliament was dissolved and a free election took place. In May 1660 the new Parliament invited Charles II, son of Charles I, to return to England from exile and become king.

Two decades of political turmoil had come to an end. What had been gained? One of the main causes of the war had been taxation by means of the royal prerogative, reflecting the major problem of paying for the government. Nothing in this respect had changed at all. Taxation was much worse than under Charles I. Both the Republic and the Protectorate had continued to live just as the first two Stuarts, from hand to mouth, with plenty of unpaid debt.

45

А. Г. Минченков. «Glimpses of Britain. Учебное пособие»

And what of religion? Once there had been at least a semblance of uniformity, now there was fragmentation. During these years people had really believed that they were living through cataclysms abounding in signs from heaven, but by 1660 all had gone, and nothing had happened. People were exhausted by years of religious controversy, and the mood swayed sharply towards a more ordered faith. In 1642 the country gentry and lawyers who sat in the Commons had seen the monarchy as a threat to their property. But in 1660 the infringements of the Crown seemed negligible compared to the threats from the sects that questioned property, rank and status. Thus the new political system was an alliance between the Crown and the property-owning classes. The monarchy was now seen as the only guarantee of stability.

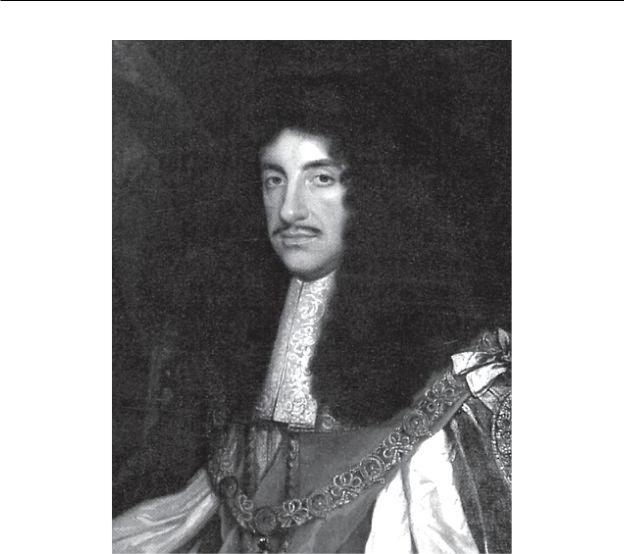

Charles II entered London on 29 May 1660. His return was a desperate attempt to re-establish equilibrium, this time going backwards to 1642. But soon people realized the impossibility of such a task. Republicanism and religious radicalism couldn’t be eradicated. They had to be tolerated. Yet the deeply rooted desire by the gentry classes for peace and social order after years of chaos and military rule was such that a veneer of stability was achieved by what was known as the Restoration Settlement. It was extremely fragile. Charles II was an exception among the Stuarts in possessing the common touch. He was affable, charming, easy-going, a lover of women and a devotee of the good life, determined never again to go into exile. Politically astute, cynical, a shrewd judge of men, Charles admired the French absolutist system, but found himself ruling over a state which, apart from the Netherlands, was an exception in the Europe of his age: its officials were unpaid amateurs, there was no adequate standing army, the Crown was impoverished, there were many faiths and Parliament existed to hinder effective government. Yet, in order to regain the throne Charles had to accept these limitations. Parliament, which for the two previous decades had acted as the executive, now reverted to its old advisory capacity and was made up again of the Lords and Commons. The royal prerogative returned, with the king having the right to conduct foreign policy, control the executive, act in the interests of the security of the state, and prorogue or dissolve Parliament. Only the Triennial Act offered any check on the sovereign ruling without Parliament, but towards the end of the reign Charles was able even to ignore that.

Financially, Charles II wasn’t in a better position than the first two Stuarts. Although Parliament now assessed the cost of government, they failed to meet it. The reason for it was that the Commons feared making the king financially independent. The result was growing debt. The government’s financial position steadily worsened. England couldn’t afford a foreign policy. Its chief aim was the struggle against the Dutch, as the main enemies of the British commercial endeavours. But the wars of 1665 and 1672 brought no real success. Matters were made worse by two disasters that struck one after the other – the Great Plague of 1665 which killed thousands, followed, the year after, by the Great Fire of London which effectively destroyed the City. In 167 °Charles signed the secret Treaty of Dover by which he became France’s pensioner, supporting the French against the Dutch. However, such a foreign policy ran counter to an increasingly antiFrench sentiment and hostility to the flaunting of Catholicism at court, by the queen, the king’s mistress and some of his ministers.

46

А. Г. Минченков. «Glimpses of Britain. Учебное пособие»

Charles II

Both Crown and Parliament were united in disbanding the New Model Army, feared as the seedbed for radical social ideas. But it was replaced by an anachronism – locally raised militias under the control of the gentry. Only reluctantly, as a result of a minor uprising, did Parliament agree to a small standing army.

Religion remained the most difficult problem of all. The king himself was liberal in outlook, anxious to achieve a compromise in which Presbyterians (supporters of the 1643 Solemn League and Covenant establishing the Presbyterian Church in England), who had helped him regain the throne, might be accommodated within a revived Church of England. The result was failure. The parliamentary election of 1661 brought hundreds of enthusiastic royalists and Anglicans into the House of Commons. The resultant ‘Cavalier Parliament’ was in a position to restore Anglican supremacy and all over the country loyalty to the old Anglican form of worship reasserted itself.

The Cavalier Parliament passed a series of acts known as the Clarendon Code after Edward Hyde, the Earl of Clarendon, Charles’s chief minister at that time. These acts included the Act of Uniformity requiring all clergy to use the revised Book of Common Prayer in their services. Onefifth of all clergy refused. They joined the ranks of the Dissenters or nonconformists who faced various restrictions and penalties. Thousands of nonconformists in England and Scotland went into hiding or were imprisoned. For the first time an official split within Protestantism in the country was recognized. A new religious underclass was created, one which joined the Catholics, suffering persecution and social disabilities, such as exclusion from all public offices and the universities.

47

А. Г. Минченков. «Glimpses of Britain. Учебное пособие»

Thus the high-ranking country gentry reasserted their position as mediators between Crown and people; they were unpaid servants of the government in the shires, the officers who kept peace and order, administered justice, controlled the militia. In return they received honours, offices, favours at court.

After the fall of Clarendon (1667) Charles decided to direct affairs himself, relying on five unofficial advisers who, for various reasons, supported the king’s efforts to relax the Anglican supremacy. This group of advisers came to be known as the Cabal because their initials spelled ‘cabal’ (Clifford; Ashley, later Earl of Shaftesbury, Buckingham; Arlington; Lauderdale). A major attempt to alleviate the position of Catholics was made in 1672, with the king issuing the Declaration of Indulgence which allowed Catholics to hold services in private and Protestant dissenters to worship. So strong was the reaction of the Anglican royalists in Parliament that they threatened to curtail the royal finances. The king was forced to withdraw the Declaration. Parliament went ahead and passed the Test Act: everybody holding public office should swear loyalty to the Established Church. As a result many Catholics lost office, the Cabal broke up and it was revealed that Charles’s brother and heir was a secret Catholic.

In this atmosphere the so-called Popish plot was concocted by two Anglican clerics Oates and Tonge. Together they fabricated the details that included England being invaded by French and Irish forces, murder of the king and accession of his Catholic brother James, Duke of York. Charles II realized from the start that it was pure fantasy, but the Plot unleashed anti-Catholic hysteria on a grand scale and led to the campaign to exclude the Duke of York from the succession. This in turn precipitated the emergence within Parliament of recognizable parties. Already there was a group cultivated by the government – a ‘court party’ and a loose association of rival factions gravitating towards Shaftesbury who were opposed to the government and formed the ‘country party’. Now in the face of the crisis the groups were to harden and gain names. The ‘court party’ got the name Tory (a term for Irish cattle thieves). They were Anglicans who regarded the Crown as sacred. Their opponents of the ‘country party’ came to be known as the Whigs (political heirs of the Puritan opposition to Charles I, although the term originally referred to Scottish robbers who murdered their victims). The Whigs believed that sovereignty was a trust from the people which would be betrayed if a Catholic were ever allowed to succeed, they favoured limitations on royal power, toleration of Protestant Dissenters and were militantly anti-Catholic. Their supporters came largely from the city merchants and several powerful aristocratic families.

The Exclusion Crisis dominated the period 1679–1681. For 3 years Charles weathered the attacks by the only weapon he had, the royal prerogative, by which he had the right to prorogue or dissolve Parliament. Charles also invited in the government as many Whigs as he could. Significantly, the Parliament of 1679, which had a Whig majority, passed the Habeas Corpus Act which prevented arbitrary imprisonment and insured a speedy trial. In 1681 the king dissolved Parliament for a third time and it was never to meet again until his death in 1685. The king had ostensibly won, but this was to leave a significant legacy. The battle had given rise to an organization on a scale of a political party. The Whigs had their leader, Shaftesbury. The alliance stretched across the country. For the moment, however, the royal finances, thanks to the commercial boom, a renewal of the French pension and reforms of the Treasury, gave the king unprecedented independence.

An important development that contributed to the success of the Crown was the Commercial Revolution. It led to a new prosperity which was founded largely on the Navigation Acts, setting limits on foreign shipping in English ports. By the late 1660s England was rapidly developing the largest merchant fleet in Europe. In the countryside there was increased activity. Agricultural methods were improved. There was a huge expansion in the coal industry. Protestants refugees from abroad brought new skills and techniques. The standard of living of most classes rose steadily in the late 17th century. England was rapidly developing into a consumer society, with a huge

48

А. Г. Минченков. «Glimpses of Britain. Учебное пособие»

growth in the domestic market. The social pyramid flattened. Although Charles created 40 new peers, about 50 % of all land belonged to the gentry classes whose numbers multiplied. As a class they were now far more stratified, with baronet at the top, a title introduced by James I, midway between a lord and a knight. After the baronets came knights and then untitled gentlemen (squires), some of whom could be wealthier in land than their titled superiors.

More important for the future was the emergence of the professions: law, medicine, the army, the church, the universities and teaching. For the first time those who spent their lives in the government emerged as identifiable group, later called civil servants.

Down the social ladder came craftsmen, shop– and inn-keepers. They all shared in the new found prosperity of the Commercial Revolution.

When Charles II died there was little to suggest that the accession of James as king would signal any dramatic change of direction. Indeed the Parliament which he summoned was Tory almost to a man. Yet James II was very different from his brother; he was cold, arrogant, believed in iron discipline and the divinity of kings. His open commitment to the Catholic cause was to be his ruin. If he had remained Anglican, history would have taken a different direction, for a monarchy firmly in alliance with the Church of England and the Royalist Tories in the shires would probably have succeeded in transforming the country along the lines of the French monarchy into an absolutist state.

What is astonishing is that he was able to take his personal policy so far and it was not until the spring of 1688 that matters came to a head. The reason for this delay was fear of a repetition of the Civil war. One thought dominated the king – how to make England safe for Catholics and convert the country back to Rome. First James introduced Catholics into the army and central government, then in the localities. In January 1687 he appointed 500 new Justices of the Peace, over 60 % of which were Catholics. By March 1688 about twelve hundred people had been removed from office and replaced by Catholics. There was, however, still no sign of public resistance, for obedience and non-resistance to the Crown was part of the creed of the Tories.

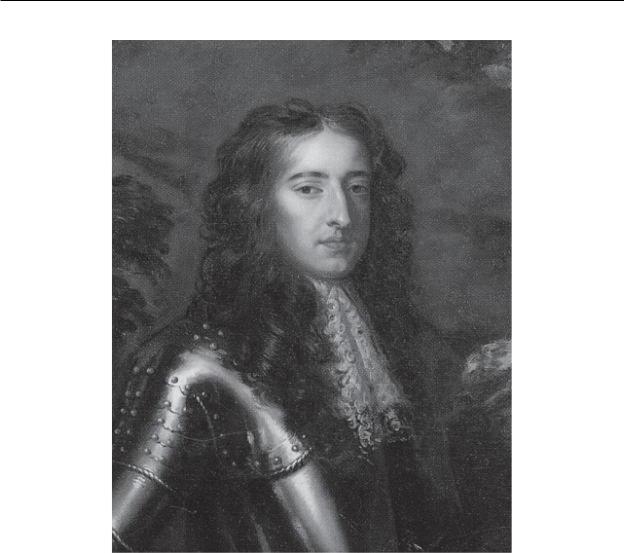

In early 1688 James’s second wife, Mary of Modena, was still childless and his heir was his eldest daughter, Mary, staunchly Anglican, who had been married to the ruler of the Protestant Netherlands, William of Orange. It was to William that some members of the English nobility finally began to make overtures to intervene. Yet at that time no one could have foreseen that by the end of the 1688 James would have fled and William and Mary would have replaced him. The events were precipitated by the birth of King James’s son in early June 1688, who became Prince of Wales in place of his Protestant half-sister, Mary. The prospects of a Catholic dynasty and the exclusion of Mary from the throne dismayed many people.

49

А. Г. Минченков. «Glimpses of Britain. Учебное пособие»

William III

In late June a formal letter of invitation was sent to William asking him to invade the country, though very few of the nobility actually signed it. Across the Channel a large army and fleet began to be assembled. But James and his ministers didn’t believe until the middle of August that it was destined for England, they thought it would be sent against France. When the truth was realized panic set in at court, but it was too late. Luck was on William’s side almost all the time. The French completely misjudged the situation and stood by while their pensioner was losing his throne, which passed to their worst enemy. Besides, James believed that William would never attack his own father-in-law. So it was only by the end of September that the king had accepted the fact that England was to be invaded. Finally government lost its nerve and it was fatal, for the king was still powerful – the army was loyal, there was no rebellion in the regions. When William landed in the south-west James delayed battles, he gave way to depression and returned to London. The result was disaster. On his return he learnt that his second daughter, Anne, had deserted him. His thoughts turned to flight. The first attempt was unsuccessful, he was recognized, but the second was a success, for William made no attempt to stop him. Still, William wasn’t king yet and there was no mention of it, but when James was gone he alone held all the cards ensuring the stability of life and property. A hasty election was called. No one in Parliament wanted the repetition of the events of the1650s. The problem was how to make legal William’s seizure of power by force. Thus on 6 February 1689 Parliament voted that the throne was vacant and the king, through fleeing, had abdicated. Parliament offered the crown to Mary and William jointly, although William had no legal claim at all. This ‘unexpected’ (according to Gilbert Burnet, Bishop of Salisbury) revolution

50

А. Г. Минченков. «Glimpses of Britain. Учебное пособие»

proved bloodless, which was due not only to James’s failure to go to battle, but also to the support of the Anglican Tory gentry, whose main aim now, as in 1660, was to preserve their hold on political power. Since the revolution was successful, supported by the respectable members of society and, above all, bloodless, the label ‘Glorious’ was soon attached to it. Those who refused to accept the new state of things and believed that James II was still the only legal monarch became known as Jacobites.

The Civil War and the Protectorate delayed the arrival of the baroque style in England. It was not until the 1690s that England was to produce its own outstanding Baroque architects in Nicholas Hawksmoor, William Talman and Sir John Vanbrugh. Baroque was a very expensive style and much as Charles II wanted to imitate the building projects of Louis XIV of France he never got his own Versailles. Not one of Charles II’s major projects was ever finished. For example, during the 1660s John Webb was called upon to design a new Greenwich Palace and one block of this began to arise, but following the Great Fire of London work on the palace ceased in 1669 and the whole project was finally abandoned five years later. The king, however, spotted the architectural genius of Christopher Wren, who became Surveyor-General of the King’s Works in 1669 and transformed it into a training ground for the Baroque architects who were to dominate the 1690s. Wren’s most enduring legacy is connected with the rebuilding of the City churches and St. Paul’s Cathedral (between 1675 and 1710) in London.

After 1688 the Crown was eclipsed by the aristocracy in terms of building projects. As a result of the French wars the Commercial and the Glorious Revolutions, the aristocracy, especially the Whig aristocracy, reached the summit of its authority. Both political and cultural power moved sharply away from the monarchy to the aristocratic grandees, whose domains became ever larger, a fact reflected in the creation of no less than nine dukedoms between 1688 and 1714. The aristocratic building boom started in the 1690s. William Cavendish, to be created 1st Duke of Devonshire in 1694, transformed the old Elizabethan house at Chatsworth. [66; 72] Initially intending to alter only the South Front, he found building so exciting that once he started he could not stop. William Talman, of the new generation of English Baroque architects, designed the South and East Fronts; the West Front was perhaps designed by the Duke himself. The new Chatsworth was finished just before the Duke died in 1707.

A steady series of lavish and large country houses began to arise. The two greatest masterpieces of the Baroque style were Blenheim Palace [58; 59; 60] and Castle Howard [55], designed by Vanbrugh. Blenheim, built between 1705 and 1724, was the nation’s tribute to its greatest military hero John Churchill, the 1st Duke of Marlborough. Castle Howard, begun in 1699 and completed in 1712, was built for Charles Howard, 3rd Earl of Carlisle. In the 20th century it served as a source of inspiration for Evelyn Waugh in his Brideshead Revisited.

The building boom was matched by a similar one in gardens as magnificent gardens were laid out across England in the formal Baroque manner.

Ironically, the new style used by the Whig aristocracy which had displaced a monarch was precisely that promoted by the Stuarts after 1660 as an expression of their aspiration for absolute power.

William III was never a popular king. He was cold and withdrawn, his manner stiff and formal; above all, he was a foreigner. But he was a formidable statesman and general. He saw the island from a European perspective. England, with all her vast commercial, financial and naval

51

А. Г. Минченков. «Glimpses of Britain. Учебное пособие»

resources, was to be used as part of a Grand Alliance against France. No one could have expected that the struggle was to involve two huge wars and 19 years of fighting, and that Britain would emerge from it as a Great Power.

In spite of the tremendous importance of the country’s military struggle against France, perhaps even more important for its future was the constitutional settlement. That fundamentally changed the nature of royal power, creating the new political phenomenon of King in Parliament, which means the abandonment of the Divine Right of kings and the recognition of parliamentary ‘sovereignty’; henceforth the right of English kings to reign was to be of human origin, the Crown would only be sovereign by the will of Parliament. From 1689 onwards no king ever attempted to govern without Parliament or contrary to the votes of the House of Commons. William III was in effect the first elective monarch. He himself was never to acknowledge that his position was in any way different from that of his predecessors, but in truth it was. The Bill of Rights, which Parliament passed in 1689, propagated the view that monarchy existed subject to conditions. The king could no longer maintain a standing army in peacetime or levy taxes without the consent of Parliament. No longer could a monarch attempt a personal rule. The Triennial Act of 1694 ensured that the maximum life of any Parliament would be three years, at the end of which an election was obligatory.

All Catholics were excluded from the line of succession. The Toleration Act of 1689 offered some freedom of worship to Protestant Dissenters, although they remained second-class citizens. The Roman Catholics obtained no legal relief, and from time to time fresh laws were passed against them. But in practice the policy of William and the spirit of the times gave them a considerable degree of free religious worship. Worship in private houses was hardly ever interfered with, public chapels were erected and priests often went about openly in spite of the laws. What was fully preserved until the 19th century was religious tests. Persons who wouldn’t take the Communion according to the rites of the Church of England were still banned from taking office either under the Crown or in the localities; the doors of Parliament were still closed to Roman Catholics, and the doors of the Universities to Dissenters of every kind.

The principal institutions of Church and State remained on the foundations of the Restoration Settlement. The full executive power was vested in the king, thus monarchy and government remained inseparable. Ministers continued to be chosen and appointed by the monarch. Indeed ministers could only remain in office as long as they retained royal favour. They also depended on the support in Parliament of those who received benefits from the Crown. The king had at his disposal a huge number of offices and pensions, which he was to retain into the 19th century. His control of foreign policy continued unassailable.

Until 1694 William reigned together with Mary, but in 1694 she died and he became the sole king. In 1701 Parliament passed the Act of Settlement. It provided that the crown should next go to Anne (second daughter of James II) and then, if she had no living children, to Princess Sophia, granddaughter of James I who ruled the small state of Hanover in northwest Germany. Significantly, the Act further restricted royal powers: judges could no longer be removed from office by the Crown (thus the judiciary was made independent of the executive), and royal officials were excluded from the House of Commons. In 1702, when William died, the crown duly passed to Queen Anne (1702–1714), who was to be the last Stuart monarch.

For most of her reign the country was dominated by a war. The War of the Spanish Succession (1701–1713), just as the Nine Years War (1689–1697) before it, was about curtailing French ambitions to dominate Europe. The English commander-in-chief in this war was John Churchill, Earl of Marlborough, who in December 1702 was created Duke of Marlborough. In 1704 he defeated the French army at Blenheim. For that Queen Anne bestowed on him the royal manor of Woodstock on which Blenheim palace was erected as a monument to his glory. A long series of English victories followed: Ramillies in 1706, Oudenarde in 1708 and Malplaquet in 1709.

52

А. Г. Минченков. «Glimpses of Britain. Учебное пособие»

Towards the end of the war Marlborough was dismissed on a trumped-up charge and on 17 April 1713 the Treaty of Utrecht was concluded. It was a turning point in the country’s history. By the year that Queen Anne died Britain enjoyed an international status unknown since the days of her greatest medieval kings. Britain emerged with concessions that began to form an empire: Hudson Bay, Newfoundland, Nova Scotia, Minorca and Gibraltar. It was recognized as a major military power and the leading naval power.

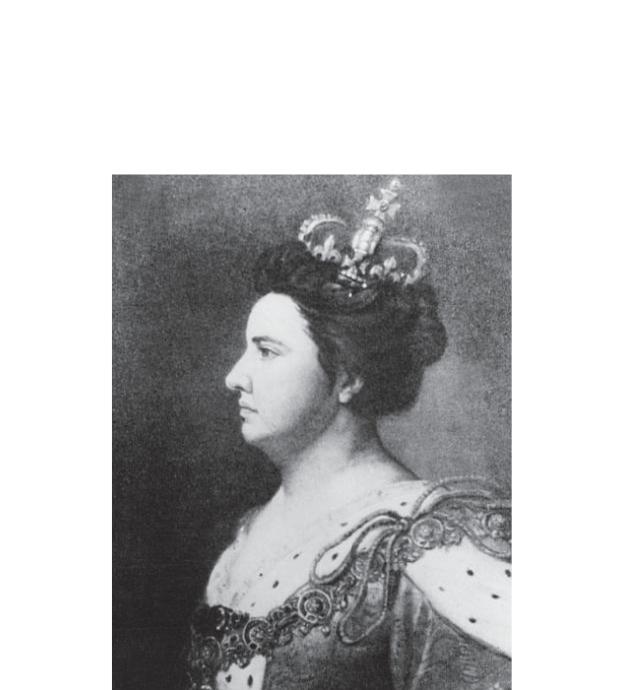

Queen Anne

The “unexpected” revolution ushered in many years of political instability when society was split from top to bottom, Whig or Tory, court and country. Both parties engaged in political debates, made more acute by the emergence of newspapers. By 1700 there were 20 of them. At that time there was no question of a government formed by one party only. Both William and Anne would have regarded this as an infringement of their royal powers. So selected aristocrats acted as “managers” putting together a government made up of rivals. One ministry succeeded another in confusion. The fact that these frequent reversals didn’t result in a breakdown was due not only to the fact that the moderates on both sides held similar views, but also to the profound changes that were taking place and eventually gave Britain its unique stability in the 18th century. During the 30 years after 1689 the civil service trebled in size. New kinds of civil servants emerged. These developments increased the power of the Crown which had an ever-growing army of official posts in its giving. The men who worked in these departments were professionals and often got proper

53

А. Г. Минченков. «Glimpses of Britain. Учебное пособие»

salaries, unlike their predecessors who made their living through fees and benefits. Government thus became a profession.

Another great change that contributed to stability was the financial revolution. The war with France was responsible for finally changing the notion that kings should ‘live of their own’. The basic principle was accepted that the government had to be paid for. In 1698 Parliament swept away the distinction between ordinary and extraordinary expenditure. Instead the king was voted for life what was called “the civil list”, which comprised the expenses of his household and the cost of the civil government. All other expenses had to be met by taxes raised and voted for by Parliament. For the first time the Land Tax was introduced, a tax on the rents and produce of land and real estate. The royal debts were converted into the National Debt, a system whereby Parliament raised money from the public for loan to the king’s government. The Bank of England was founded in 1694.

In 1707 Parliament passed an Act of Union – uniting England with Scotland, and in October the first Parliament of Great Britain met, though Scotland retained its own legal system.

So called Queen Anne style usually refers to a style popular in the early 18th century and characterized by Dutch-looking red-brick construction with classical ornamentation. Queen-Anne houses are usually relatively small and unimposing. One of such houses is Mompesson House, Salisbury. [75]

So called Queen Anne style usually refers to a style popular in the early 18th century and characterized by Dutch-looking red-brick construction with classical ornamentation. Queen-Anne houses are usually relatively small and unimposing. One of such houses is Mompesson House, Salisbury. [75]

An essential part of Queen Anne’s public and private life was her relationship with the Marlborough family, especially Sarah, the Duchess of Marlborough. This subject has traditionally attracted both historians and writers of fiction, and has given rise to a number of historical anecdotes, the most famous of which is perhaps the thrown water anecdote. According to Voltaire, ‘If the Duchess of Marlborough had not thrown a glass of water in the face of Lady Masham, and some drops on Queen Anne, the queen wouldn’t have thrown herself into the hands of the Tories and wouldn’t have given to France a peace without which France couldn’t have sustained itself.’ This description, either apocryphal or metaphorical, refers to the Treaty of Utrecht, which was allegedly concluded owing to this incident. In truth, the causes of the peace treaty were far more complex, but the thrown water was enough to inspire the French dramatist Eugene Scribe in 1900 to write an entire play about Sarah called Le Verre d’eau ou les effets et les causes. Based on an anecdote, this play served to propagate a number of persistent historical errors that rather distort the historical perspective.

Lady Anne and Sarah Jennings first met as children at play in 1670 or 1671. Yet there is nothing to suggest that their relationship was especially close before 1682. By that time Sarah was already married to John Churchill and was well established in the Duke of York’s household and Lady Anne’s circle. Lady Anne herself was married in 1683 to Prince George of Denmark, who as a devout Protestant was politically acceptable to England. The general estimate of his abilities was summed up by Charles II in his famous phrase ‘I’ve tried him drunk and I’ve tried him sober and there is nothing in him’. The judgement seems to have been accepted by everybody except Lady Anne herself, who was to remain blindly devoted to her husband throughout her married life. Anne’s alienation from her Catholic father and stepmother (which was due to religion and her own dynastic ambition) and the mutuality of interests which, as a young mother, she shared with Sarah, led to her increasing dependence upon Lady Churchill. Another reason for Anne’s devotion to Sarah was probably her conviction that the latter would never

54

А. Г. Минченков. «Glimpses of Britain. Учебное пособие»

flatter her or tell her a lie. Having grown up in a court where intrigue and backstabbing were rampant, Lady Anne appreciated Sarah’s undoubted honesty and integrity. Later Sarah herself attributed the friendship to the mediocre personalities who surrounded Lady Anne.

Sarah, the Duchess of Marlborough

The 1690s proved to be a crucial decade in Anne’s personal and political development. It was her own decision to go into opposition to William and Mary, and when Marlborough was dismissed by William and the queen demanded the removal of Sarah from her sister’s household Anne blatantly refused and stoically weathered the social ostracism that followed. After 1691 the correspondence between Anne and Sarah was to be conducted under the names of Mrs. Morley and Mrs. Freeman respectively. During this period, up to Anne’s accession to the throne the two women probably enjoyed the closest relationship possible.

Things began to change when Lady Anne became queen. In the eyes of the public the Marlboroughs, and Sarah in particular, had achieved the summit of their ambition – for most of Anne’s reign the world believed that she was just a puppet of the Marlboroughs. Psychologically, this belief can be explained by the queen’s personal shyness, reticence and isolation from society, on the one hand, and Sarah’s formidable and powerful personality, on the other. True, Sarah’s social position greatly improved as a result of Anne’s accession. She was now Groom of the Stole, Mistress of the Robes and Keeper of the Privy Purse. These were

55

А. Г. Минченков. «Glimpses of Britain. Учебное пособие»

three of the top posts in the queen’s household, and certainly the most lucrative that could be awarded to a woman. They gave Sarah a personal income of Ј5,600 per annum (approximately Ј400,000 in today’s money). As Groom of the Stole she was responsible for the queen’s bedchamber and personal attendants and was given ten rooms at Kensington Palace. [74] As Mistress of the Robes, Sarah also appointed and oversaw the Robes staff, and the office of the Keeper of the Privy Purse placed her in charge of the queen’s personal finances. The symbol of Sarah’s power in the household, representing her unique access to the Queen, was the Gold Key. It opened the doors of the bedchamber, other private rooms and galleries, State and reception rooms, and all the garden gates. It is little wonder that all these outward symbols of power made an impression on the general public, foreign diplomats and even people who had a high position in society. Yet, as they say, appearances are deceptive. In reality, Sarah’s influence on the queen and the political life of the country was much less powerful than it was, and sometimes still is, commonly supposed. The explanation lies in the character of the queen and the realities and attitudes of the early 18th century.

The standard picture of Queen Anne as a weak, irresolute woman, dominated by favourites and deciding high policy on the basis of personalities was largely propagated by Sarah herself when the friendship was over, especially in the famous work she wrote long after the queen’s death, the Conduct of the Dowager Duchess of Marlborough (1742). In fact, the events of the queen’s life had established the tenacity and independence of her character. Always her own woman, she had intrigued against her father and defied William and Mary. Although virtually an invalid at the time of the accession (her health broken as a result of seventeen pregnancies during the first seventeen years of marriage – to produce a healthy heir was her greatest unrealized ambition) Anne proved to be one of the most industrious British monarchs. It would be inaccurate to date the decline of modern royal power to Anne’s reign. She was so fearful of being seen as just a figurehead or a cipher that she performed her duties with extraordinary diligence. By that time the unwieldy Privy Council had been replaced by a ‘cabinet committee’, or the Cabinet, as the main government decision-making body. Most significant was that no meeting of the Cabinet could take place without her, and the membership depended solely on whom she summoned to attend. Outside the Cabinet, Anne had the right of veto in the Houses of Parliament (which she used in March 1708). During her reign the key debates took place in the House of Lords, which the queen regularly attended and subtly influenced by ignoring some speakers and taking notice of the others. Technically she was head of the executive, the legislature, the judiciary and the Church of England. Determined to be taken seriously, Anne was not prepared to be seen running her government on the basis of a female friend’s opinions. She denied Sarah the political influence that her intelligence and ambition demanded and wished for their friendship to be merely romantic. In those times sentimental friendship among women was supposed to be immune from political divisions since a woman, unless she was a sovereign, wasn’t expected to meddle in politics and indeed couldn’t hold a political office. But while the queen wanted her friend to discuss only things like clothes and the weather, Sarah obviously thought otherwise. During the summer and autumn of 1702 she started a campaign to convince the queen that the Tories were her secret enemies and Jacobites, while her only hope of retaining the crown rested with the Whigs. In general, the whole idea of parties was anathema to the queen,

56

А. Г. Минченков. «Glimpses of Britain. Учебное пособие»

who entertained the Elizabethan concept of national unity, in which parties were equated with national division and weakness. If anything, her natural inclination at that time lay with the Tories, who in her view had consistently supported and defended the Church of England. Anyway, she refused to be influenced by Sarah’s propaganda. Thus the alienation between the two friends began almost as soon as Anne became queen, but it was vastly accelerated after the death of Sarah’s only son (1703), when she began to absent herself from court for long periods of time, often neglecting her duties to the queen. At the same time her verbal bombardment of her friend and sovereign continued, causing further tension. The friendship was finally destroyed when in 1707 Sarah learnt that the queen’s bedchamber woman Abigail Masham (nйe Hill), a relation of the Duchess appointed to the post as early as 1697, had become her favourite and confidante. The Duchess wrote angry and often tactless letters, and in 1710 went so far as to threaten to publish the queen’s letters to herself. For several years the queen was in alarming dilemma: she had to retain Sarah in office as she couldn’t afford and didn’t wish Marlborough’s resignation, but that meant that the personal contact between the two women would, of necessity, continue. Sarah was finally made to resign in 1711, long after she ceased to have any influence on the queen, so that the conclusion of the War of the Spanish Succession had nothing to do with her.

The Duchess of Marlborough survived the queen by 30 years and died in 1744 one of the richest women in Britain. She was the founder of the powerful Spencer-Churchill family and an ancestor of both the present Duke of Marlborough and Lady Di.

57