A Dictionary of Archaeology

.pdfhuman history and the Stone Age succession in Africa. At the same time Leakey denied that Zinjanthropus was the toolmaker or even an early form of human, but assigned it to the genus of nearhumans, AUSTRALOPITHECUS, already recognised in South Africa. By designating this species

Australopithecus (Zinjanthropus) boisei, Leakey further argued that another bipedal species was represented among the Olduvai fossils in the same geological beds, one with a bigger brain and more adept hands. This one, which he regarded as human and the early stone toolmaker, he named HOMO HABILIS. Despite initial doubts about Leakey’s ‘juggling’ of the pieces of skulls and limb-bones and criticisms of the sensational manner of announcing scientific discoveries, this view of the earliest tool-making humans existing alongside australopithecine hominids in eastern Africa about two million years ago has prevailed in outline.

Further important fossils, of both Lower and Middle Pleistocene age, were found at Olduvai in the early 1960s, and Mary Leakey continued working there long after, concentrating on the lithic sequence and interpretation of site-activities, while Richard Hay completed a parallel study of the complex volcanic and lacustrine geology. With further fossil discoveries in the region and also in northern Kenya and Ethiopia, the Olduvai discoveries came to be viewed in fuller context. This showed that earliest mankind, Homo habilis, extended back beyond the Olduvai sequence to perhaps 2.5 million years; while australopithecines, from which earliest Homo would have emerged in time, stretch back to twice that age. The matching of the australopithecine skeleton (nicknamed ‘Lucy’) found at HADAR in the eastern Ethiopian Rift Valley with the footprints unearthed by Mary Leakey at LAETOLI, near Olduvai, under volcanic ash dating to 3–4 million years ago, demonstrates, despite notorious academic rivalries and scientific disputes, the essentially collaborative and accumulative nature of the advancement of knowledge of human evolutionary history in the changing African environment of the whole Pleistocene span.

L.S.B. Leakey et al.: Olduvai Gorge I–V (Cambridge, 1965–94); R.L. Hay: The geology of Olduvai Gorge

(Berkeley, 1976); J. Reader: Missing links: the hunt for earliest man 2nd edn (London, 1988).

JS

Oleneostrovski mogil’nik (‘Oleneostrovski cemetery’) The largest MESOLITHIC cemetery in Europe is on the Oleni (Reindeer) island in Onega Lake, in Russian Karelia. Excavated by A.I.

OLMEC 445

Ravdonikas in 1936–8 and N.N. Gurina in the 1950s, the total number of graves is estimated at more than 400 (170 were excavated). The burials were 0.60–1.20 m below the ground surface, usually singly (16 double burials and three triple burials), in an extended posture facing east; after inhumation, the bodies had been sprinkled with red ochre. Four individuals in the northern part of the cemetery were interred in funnel-shaped shafts 1.3–1.8 m deep, in a standing posture facing west.

Hunting equipment (such as bone and stone points, bone daggers, slate knives, harpoons, fishhooks and quivers) prevails in male graves. Female graves, in general poorer than the male examples, contained household artefacts, flint blades, awls, polishers, burins and scrapers, as well as perforated beaver incisors and snake-effigy figures. One of the shaft graves contained six beaver mandibles. The grave goods included 42 sculptured or ornamented objects, including representations of elk, snakes and humans carved in stone, wood and bone. After a multivariate analysis of the grave goods, O’Shea and Zvelebil (1984) concluded that the cemetery belonged to a relatively large and stable population with considerable internal social differentiation. It also seems that there was an active regional exchange network which included a wide variety of raw materials and exotic goods (e.g. arrowheads and knives made of grey flint). A recent series of radiocarbon dates suggests a time-span of 6500 to 6300 BC in calendar years.

N.N. Gurina: Oleneostrovskii Mogil’nik, MIAS 47 (Moscow and Leningrad, 1956); J. O’Shea and M. Zvelebil: ‘Oleneostrovski Mogilnik: reconstructing social and economic organization of prehistoric forages in northern Russia’, JAA 3 (1984), 1–40.

PD

Ollantaytambo see INCA

Olmec Name given to the Middle Formative society that flourished on the Gulf coastal plain of Veracruz and Tabasco, Mexico, c.1400–400 BC. The term ‘Olmec’ also refers to an unrelated group of 16th-century peoples in highland Puebla, Mexico, but when used by archaeologists ‘Olmec’ almost invariably refers to the Formative period culture.

The Gulf coast Olmec were one of several complex societies to develop out of late Preceramic and Early Formative village traditions in Mesoamerica and during the Middle Formative these groups maintained extensive contacts with each other. The precise origins of Olmec culture are still being

446 OLMEC

debated, as there is little evidence for large Early Formative populations in the region. Many archaeologists see evidence of ties to Pacific coastal regions of Chiapas and Guatemala and the trans-isthmian zone. The Gulf coast’s broad rivers and fertile floodplains would have been attractive to early farmers.

Most sites in the Olmec area are relatively poorly known archaeologically, the exceptions being SAN (see Coe and Diehl 1980) and LA VENTA. These and other Olmec sites

provide evidence for the early development of some of the characteristics of public architecture in Mesoamerica, chiefly the construction of pyramidal mounds and their arrangement around open plazas. Mounds at Olmec sites are constructed of earth, with floors and surfaces of different coloured clays and sands. Olmec culture traditionally has been best known through its art style, which featured monumental basalt stone sculptures in the form of human heads, possibly representing Olmec rulers, and ‘altars’, perhaps serving as thrones. Portable art included carved objects of green stone (jadeite, serpentine, or other minerals), often depicting a

‘WERE-JAGUAR’.

Objects in the Olmec style have been found widely throughout Mesoamerica during the Middle Formative period at sites such as CHALCATZINGO and Oxtotitlán (a cave in Guerrero, best known for its Olmec-related painting of a costumed figure in a green bird suit, seated atop an altar or throne). Olmec objects include pottery with ‘Olmec-like’ motifs, carvings and paintings in the ‘Olmec style’ and other ‘Olmecoid’ artefacts. They are usually found together with objects of local manufacture and local stylistic traditions. It is clear from these distributions that much of what is distinctively Gulf coast Olmec was transmitted to other groups in Mesoamerica, but the meaning and mechanisms of this transmission are uncertain. Interpretations have generally been polarized into two camps. One view of the Olmec sees them as Mesoamerica’s first civilization, the cultura madre, and the Olmec are credited with bringing civilization to the rest of the region through trade, religious proselytization or political unification (see Coe 1968). Another view sees the Olmec as one of many Middle Formative societies in Mesoamerica (see PASO DE LA AMADA; SAN JOSE MOGOTE) in which elite groups were emerging and competing for resources (see papers in Sharer and Grove 1989); the widespread stylistic features are interpreted as part of shared ideology, kin identification, and/or systems of status symbols.

M.S. Coe: America’s first civilization (New York, 1968); M.D. Coe and R.A. Diehl: In the land of the Olmec, 2 vols (Austin, 1980); E.P. Benson, ed.: The Olmec and their neighbors (Washington, D.C., 1981); R.J. Sharer and D.C. Grove, eds: Regional perspectives on the Olmec (Cambridge, 1989).

PRI

Olorgesailie One of the best studied ACHEULEAN sites of between 0.5 and 1 million years ago, situated low in the Eastern Rift Valley in southern Kenya. Olorgesailie was from time to time a favoured lakeor waterside site at which groups of HOMO ERECTUS hunter-gatherers camped, perhaps seasonally. The concentrations of handaxes, cleavers and other tools and debitage result from erosion and mixing in small gullies; nevertheless, working from their spatial distribution and associations, as well as the environmental pointers provided by the deposits themselves and fossil bones of various animals, Glynn Isaac produced a classic study of site-use, activity patterns and economic exploitation of local resources in the Early Stone Age. Together with work at other eastern African Acheulean sites (ISIMILA, NSONGEZI,

OLDUVAI and KALAMBO FALLS) in the 1960s,

Olorgesailie in Isaac’s interpretation illustrated the employment within a single population of varied tool-kits for different activities – from butchering and skinning to woodworking and heavy-duty pounding and digging – as opposed to the traditional archaeological fashion of defining ‘cultures’ and their successions by specific diagnostic stone tools.

G.Ll. Isaac: Olorgesailie (Chicago, 1977).

JS

Olsen-Chubbuck PALEO-INDIAN kill site in Colorado, dated to 8200 BC, containing Planview projectile points of the PLANO Culture associated with the remains of extinct species of bison. A herd of bison was driven into a gully and about 200 animals of all ages and both sexes were killed. The first animals in the gully were trampled by the stampeding herd behind them and the later animals were killed by hunters. Only a few of the animals were butchered. Disarticulation patterns revealed that the animals were systematically butchered and that animal parts varied in value.

J. Wheat: ‘A Paleo-Indian bison kill’, Scientific American 216/1 (1967), 44–53.

WB

el-Omari Group of Egyptian Neolithic sites about 12 km south of Cairo, consisting of three settlements and two associated cemeteries, which form the basis for the el-Omari phase of the Lower Egyptian predynastic. Despite some dispute over the radiocarbon dates from the el-Omari sites, the two main settlements (el-Omari A and B) are now thought to have been occupied throughout the 4th millennium BC, making them roughly contemporary with the late Amratian and Gerzean phases in Upper Egypt (see EGYPT: PREHISTORIC). Both elOmari A and B comprised numerous circular wattle and daub huts, as well as storage pits, with tools and organic remains showing that they cultivated emmer wheat and barley. They buried their dead within the confines of the village, equipping them with relatively few grave-goods. The fact that the slightly later el-Omari C settlement (with which at least two separate cemeteries are associated) included chisel-shaped arrowheads suggests that it was still inhabited in Early Dynastic times (c.3000–2649 BC).

F. Debono: ‘La civilization prédynastique d’El Omari (nord d’Hélouan)’, BIE 37 (1956), 329–39; F. Debono and B. Mortensen: El Omari: a Neolithic settlement and other sites in the vicinity of Wadi Hof, Helwan (Mainz, 1990); B. Midant-Reynes: Préhistoire de l’Egypte (Paris, 1992), 118–22.

IS

Omo Early hominid site in the lower basin of the Omo river, southwest Ethiopia. The long sequence of Pliocene and Pleistocene deposits – the thickest fossiliferous stratigraphy in east Africa – have yielded many thousands of fossil remains both of early hominids and mammals such as elephants, pigs and hippopotami. The hominid remains in the earlier deposits, dated by

DATING, PALAEOMAGNETISM and faunal analysis

to about 3 million years ago (Brown et al. 1985), have been identified as Australopithecus africanus

and boisei (see AUSTRALOPITHECUS). The upper

levels contain remains of HOMO HABILIS and HOMO ERECTUS dated to about 1.4 million years ago.

M.H. Day: ‘Omo human skeletal remains’, Nature 222 (1969), 1135–8; G.E. Kennedy: ‘The emergence of Homo sapiens: the post-cranial evidence’, Man 19 (1984), 94–100; F.H. Brown et al. ‘An integrated Plio-Pleistocene chronology for the Turkana basin’, Ancestors, ed. E. Delson (New York, 1985), 82–90.

IS

Ongbah Large cave containing rich burials of the 1st millennium BC, located in the upper reaches of the Khwae Yai River in central Thailand. Per

OPEN-AREA EXCAVATION 447

Sørensen’s research, although limited by the activities of looters, revealed that the dead were interred in wooden boat coffins, one of which has been dated to the last four centuries BC. Apart from iron implements, Sørensen has described five bronze drums of clear DONG SON affinities decorated with flying birds, human figures and geometric motifs. Bronze earrings, bracelets and a high-tin bronze bowl were also present. These rich graves contrast with ten burials without boat coffins, but containing a similar range of iron artefacts. Sørensen has suggested that the differences between these and the coffin burials reflect social status rather than chronology. The presence of such rich interments might well be explained by exchange up and down the river valley and the wealth generated from access to the local lead ores.

P. Sørensen: ‘The Ongbah cave and its fifth drum’, Early South East Asia, ed. R.B. Smith and W. Watson (Oxford, 1979), 443–56.

CH

Onion Portage Deeply stratified inland site located on the Kobuk River, Alaska. The earliest levels include remains from the Akmak and Kobuk

complexes of the PALEO-ARCTIC TRADITION. The

site appears to have functioned as a hunting station to intercept caribou crossing the river here; alternatively, it may have been used for fishing.

D.D. Anderson: ‘A Stone Age campsite at the gateway to America’, SA 218/6 (1968), 24–33.

RP

open-area excavation Style of excavation, also known as ‘open excavation’ or ‘stripping’ whereby large areas of an archaeological site are exposed, without the use of permanent BAULKS or sections, which can often have the effect of obscuring the excavator’s full view of each cultural horizon. The technique was introduced from the 1940s onwards (see, for instance, Bersu 1940) as a replacement for the earlier GRID system of excavation favoured by Mortimer Wheeler, which is unsuitable for many types of site, especially those which have little vertical stratigraphy but cover very wide areas. The open-area system was used to great effect in the influential OLD MINSTER excavations at Winchester in the 1960s. It has been found to be particularly appropriate for sites incorporating timber buildings, where it is often essential to be able to see the whole plan (e.g. the post-Roman settlement at Cheddar, see Rahtz 1979). Even highly stratified sites, such as the Romano-British settlement of Wroxeter, which would previously have

448 OPEN-AREA EXCAVATION

been regarded as prime candidates for the grid system, have been successfully excavated with the open-area method. The grid, block or trench systems are however still sometimes preferred for certain types of site, such as BARROWS or rock shelters, where it is essential to be able to see all of the stratigraphic phases at once.

G. Bersu: ‘Excavations at Little Woodbury’, PPS 6 (1940), 30–111; A. Steensburg: Farms and water mills in Denmark (Copenhagen, 1952); P.A. Rahtz: The Saxon and Medieval palaces at Cheddar (Oxford, 1979).

IS

Opone see HAFUN

oppidum (pl. oppida; Lat: ‘defended administrative centre or town’) During the later La Tène period in Gaul, from the 2nd century BC, there developed a series of large regional centres, some of which Julius Caesar in his reports of campaigns in the region, referred to as ‘oppida’ – a label that has stuck. Many of these oppida were defended, but unlike earlier hillforts of the 2nd and early 1st millennium BC, most seem to have been permanently and densely occupied. The more complex examples seem to have acted as tribal capitals, trade and distribution centres, and are often located near significant trade routes. Caesar mentions the presence of Italian merchants in some oppida. There is also considerable evidence at sites such as MANCHING in Bavaria, Germany, for a planned street lay-out, directional trade and specialized industries. Oppida probably also functioned as centres of political power, although this is difficult to prove, and they sometimes provide evidence of the minting of coinage. Because of these different functions, oppida are often held to be in some sense ‘proto-urban’, although there is little evidence of the public buildings, monumental temples and memorials that Caesar would have associated with a truly urban centre.

There is a concentration of large and apparently complex sites in France and southern Germany, but a similar phenomenon is represented by sites in eastern Europe such as Staré Hradisko in Moravia and to a much lesser extent in southern Britain – the internal evidence from massively defended sites such as DANEBURY is not as impressively complex as that from Manching. It should be noted that the term oppidum has rather different meanings to different writers: for some it should only be used when there is proof that the oppidum acted as a seat of regional power, or had a mint, while others use the term in a relative sense, to indicate a larger and more

complex than average settlement. Bradley (1984) provides a short critique of the use of the term in Britain.

R. Bradley: The social foundations of prehistoric Britain

(London, 1984), 150–2; J.R. Collis: Oppida: earliest towns north of the Alps (Sheffield, 1991).

RJA

optical emission spectrometry (OES)

Analytical technique which was one of the first to become established as a means of analysing the trace elements in artefacts made from metal, glass and pottery. Originally it required a small amount of material to be dissolved in acid, but more recently lasers have been used to vaporize small parts of the sample, making the technique essentially nondestructive. Atoms in a sample are excited by a laser beam or electrical charge. The near-ultra-violet and visible light released from them at the end of this excitation is dispersed by a quartz prism or diffraction grating and can then be analysed as a pattern of black lines on photographic film. Each element has its own characteristic wavelength, while its concentration can be estimated by the intensity of the line (measured using a densitometer). The technique can be used in provenance studies, although recent work has favoured other techniques, such as X-RAY FLUORESCENCE

SPECTROMETRY above OES.

J.S. Tite: Methods of physical examination in archaeology

(London, 1972), 260–4.

PTN

optically stimulated luminescence (OSL)

Scientific dating technique, the principles of which

are the same as for THERMOLUMINESCENCE

DATING, but light, rather than heat, is used to stimulate the emission of the luminescence signal. OSL has been developed for use on unheated sediments exposed to sunlight prior to deposition. The disadvantage of TL for such materials is uncertainty about the degree to which the geological TL signal was removed (bleached) prior to deposition. Laboratory bleaching to determine the residual signal may overor under-bleach relative to what actually happened in the past and thus lead to systematic error in the age estimate. Light stimulation on the other hand empties only the most bleachable traps and does so rapidly; it therefore mimics the natural exposure more closely, and samples that have received only a short natural exposure should nevertheless be datable.

Green laser light is most often used for quartzrich sediments and it has been found that infrared

can be used for feldspars. In both cases, the luminescence emission is at shorter wavelength which enables the detection system to be designed to discriminate against the stimulating wavelengths.

Because of the sensitivity of the OSL signal to light, samples must not be inadvertently exposed to light either during collection or laboratory preparation. For collection, either blocks can be cut from a sediment section or a container can be driven in; surfaces exposed to light are removed in the laboratory. The range of sediments to which OSL has been applied include LOESS, river channel and lacustrine silts, dune, beach and cover sands. The lower age limit is typically a few thousand years to provide a measurable signal and, in quartz, for the effect of recuperation (a non-radiation signal that grows in after bleaching) to be negligible. Upper age limits are determined by signal stability, saturation of the signal (i.e. no further growth with radiation dose) and radiation dose-rate (see THERMO-

LUMINESCENCE DATING). For the most common

feldspar signal in fine-grained sediments, the possibility of mean life of the order of 100,000 years for the stability of the luminescence centre is still a matter of some debate.

A.G. Wintle: ‘Luminescence dating of aeolian sands: an overview’, The dynamics and environmental context of aeolian sedimentary systems, ed. K. Pye (London, 1993) 49–58; ––––: ‘Recent developments in optical dating of sediments’, Radiation Protection Dosimetry 47 (1993), 627–35.

SB

oracle bones (chia-ku(wen); jiaguwen) Term used in the archaeology of China to refer to the divinatory queries and assessed divine responses recorded on animal scapulae (SCAPULIMANCY) and turtle plastrons (PLASTROMANCY) by means of incised characters. Most texts were incised directly into the surface of the bone or carapace, but in some cases tracings with styli are applied on top of prior writings with brush and ink. Pyro-scapulimancy significantly pre-dates the SHANG era (i.e. before 2000 BC) and was practiced by the Neolithic peoples of China on the bones of various animals, consisting of the incising of actual legible text.

‘Writing’, in the form of isolated symbols of probably associable meanings, exists in the incised marks on ceramics of YANG-SHAO, LUNG-SHAN, CHI’I-CHIA, and other Neolithic cultures; however, it is only in Late Shang times that the earliest instances of incised divinatory queries and answers appear in pyro-scapulimancy. The queries to the ancestors and the gods cover a multitude of subjects from harvest and rainfall to hunting expeditions and

ORCHOMENOS 449

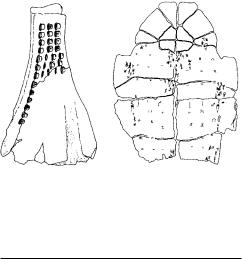

Figure 39 ‘oracle bones’ A bovid shoulder blade (scapula) and a freshwater turtle under-shell (plastron) from ancient China, both incised with the queries of diviners. Source: G.L. Barnes: China, Korea and Japan

(Thames and Hudson, 1993).

warfare. Even so mundane a matter as a royal toothache was the subject of oracular query, which generally manifested an appreciably advanced form of written expression. Since 1899, when inscribed oracle bones (then described as ‘dragon bones’) were first discovered, a vast corpus of literature has accumulated (see Serruys 1974 and Keightley 1978).

P.L.-M. Serruys: ‘The language of the Shang oracle bone inscriptions’, TP 60/1–3 (1974), 12–120; D.N. Keightley:

Sources of Shang history: The oracle-bone inscriptions of Bronze Age China (Berkeley, 1978); Takashima-Ken’ichi: ‘An evaluation of the theories concerning the Shang oracle-bone inscriptions’, Journal of International Studies

15/16 (1988–9), 11–54.

NB

Oranian see IBEROMAURUSIAN

Orchomenos Mycenaean THOLOS tomb and fragmentary ruins of a Mycenaean acropolis in Boeotia, Greece. The tholos tomb, known as the ‘Treasury of Minyas’, is the finest outside MYCENAE. It has a diameter of c.14 m, and is closely related in design to the Treasury of Atreus at Mycenae; it is probably of about the same date, soon after 1400 BC. A side-chamber preserves some of the finest Mycenaean carved stone reliefs, consisting of curvilinear and floral motifs. The nearby acropolis has yielded evidence for frescoes and large rooms – possibly indicating a Mycenaean palace complex. Heinrich Schliemann excavated at Orchomenos, and found here a distinctive wheel-made ware that

450 ORCHOMENOS

he named MINYAN WARE (after the legendary King Minyas who is associated with the site).

R. Hope Simpson: Mycenaean Greece (New Jersey, 1981).

RJA

orientalizing Term sometimes used to describe artefacts, particularly art objects, produced outside the Ancient Near East but showing the influence of eastern civilizations or cultures. An example of an ‘orientalizing’ tradition is the SITULA ART produced in the sub-Alpine region in the later 1st millennium BC.

RJA

OSL see OPTICALLY STIMULATED

LUMINESCENCE

‘osteodontokeratic culture’ see

MAKAPANSGAT

otolith Minute calcareous concretion found in the inner ear of some vertebrates, especially fish. Otoliths can be recovered by fine wet sieving of archaeological deposits and are useful indicators of fish species, size of fish and even the season in which the fish were caught.

P.A. Mellars and M.R. Wilkinson: ‘Fish otoliths as indicators of seasonality in prehistoric shell middens: the evidence from Oronsay (Inner Hebrides)’, PPS 46 (1980), 19–44.

RJA

Otsuka Middle Yayoi moated settlement and associated cemetery in Yamanashi prefecture, Japan (c.100 BC–AD 100; see JAPAN 3). An area of 130 × 200 m was enclosed by a 2 m deep and up to 4 m wide fortification ditch, probably with an outer bank. Over 90 buildings were excavated, of which up to 30 were occupied contemporaneously. These were clustered into groups of a couple of large buildings and a raised floor storehouse. The 25 ditch-and-mounded graves from the associated Saikachido cemetery, 100 m southeast of the settlement, represent the burials of an elite class who resided at Otsuka.

C.M. Aikens and T. Higuchi: The prehistory of Japan (London, 1982), 240–1.

SK

‘Oueili, Tell el- see UBAID

Overton Down Experimental earthwork in Wiltshire, constructed by a group of British archae-

ologists in 1962 as an exercise in EXPERIMENTAL ARCHAEOLOGY. Their aim was both to obtain a better understanding of the process of creating an earthwork and to find out what happened to such a monument (and various materials buried within it) through the passage of time. This was the first archaeological experiment that was designed to outlive its progenitors. The proposal was that the ditch and bank would be regularly sectioned after one year, then two years, then four years, and thereafter on a binomial progression until 128 years had passed.

The Overton Down earthwork was constructed on upper chalk on the open downs. In 1963 a second earthwork, of exactly the same proportions and design, was built on sandy acidic soil at Wareham Down. Both are linear earthworks, intended to simulate prehistoric boundaries, where the bank was set at some distance from the ditch, creating two elements rather than an integrated unit. With the advances made in scientific archaeology during the 1980s and 1990s, especially with regard to soil sciences, these earthworks have provided a wealth of invaluable data to enhance the understanding of the archaeological evidence from actual sites. The 32-year report on Overton (Bell et al. 1996) included SEM (SCANNING ELECTRON MICROSCOPE) analyses of buried materials such as wood, textiles and bone, as well as studies of soil micromorphology and chemistry.

P.A. Jewell and G.W. Dimbleby: ‘The experimental earthwork on Overton Down, Wiltshire, England’, PPS 32 (1966), 313–42; M. Bell, P.J. Fowler and S.W. Hillson:

The experimental earthwork project 1960–1992 (London, 1996).

PRE

Oxtotitlán see OLMEC

Oxus treasure Celebrated hoard of about 150 complete and fragmentary gold and silver objects (including figurines, bracelets and model chariots) and 1500 coins of uncertain provenance and mixed date, which appeared on the art market in about 1880, although they are said to have been discovered a few years earlier at or near Takht-i Kuwad by the Oxus river (Curtis 1989). Most of the objects have been identified stylistically as Achaemenid (4th–5th century BC), but many of the coins date as late as the 3rd century BC. Since the ‘treasure’ was simply sold to a British collector at Rawalpindi (now in Pakistan), its original archaeological context can now only be conjectured. It is considered likely that the dealers in Rawalpindi attempted to enhance the

value of the hoard by adding other objects of different dates and provenances (such as SCYTHIAN and Egyptian). The original assemblage was perhaps part of a temple treasury (and/or a hoard valued for its precious weight) in an Achaemenian city.

O.M. Dalton: The treasure of the Oxus (London, 1964); J. Curtis: Ancient Persia (London, 1989).

IS

oxygen isotope analysis Oxygen exists in three isotopes, two of which are important in archaeology: 16O and 18O. The latter has a natural abundance of about 0.2%. Variations in the abundances of these isotopes can arise through physical and chemical factors which fractionate between the lighter and heavier isotopes leading to changes in their isotopic ratio. The ratio (18O/16O) is usually measured by gas source mass spectrometry on samples converted to carbon dioxide. Results are expressed in the form δ18O which is the difference in the ratio in ‘parts per mil’ (parts per thousand) from a reference material. This is usually ‘standard mean ocean water’ (SMOW) with a 18O/16O ratio of 0.0020052. The δ18O value may be positive, enriched in 18O relative to the reference, or negative, depleted in 18O. The δ18O value of water is temperature-dependent and is used as a palaeotemperature indicator. Another major application of oxygen isotope measurements is in provenance studies. It has been successfully applied to Classical marble where the δ18O value, in conjunction with

that of CARBON ISOTOPE ANALYSIS, has been used

to characterize raw material sources and provenance sculpture and building stone.

N. Herz and M. Waelkens: Classical marble; geochemistry, technology, trade (Dordrecht, 1988); P.J. Potts: A handbook of silicate rock analysis (Glasgow, 1992).

MC

oxygen isotope chronostratigraphy

Method for correlating, and hence dating, deep sea sediments based on climate variations recorded in

the 18O values (see OXYGEN ISOTOPE ANALYSIS) of

foraminifera with depth. Because the oceansedimentary record is continuous, the climatic stages identified within it are used as a global reference for terrestrial sites of the Quaternary and earlier, replacing the old Ice Age system (e.g. Mindel-Riss-Würm previously used in the Alpine regions of Europe).

The 18O values of the carbonate tests of foraminifera reflect that of the surrounding waters. Fractionation (a temperature-dependent process) occurs on uptake of the oxygen, however, the

OXYGEN ISOTOPE CHRONOSTRATIGRAPHY 451

greatest effect on the 18O value of the foraminifera is ice volume. Temperature-dependent fractionation also occurs on evaporation and precipitation of water; the net result is that in a glacial period, because of the quantity of water locked up in the large ice masses, ocean waters have higher 18O values than during interglacial periods: the difference is about 1%O. The 18O value of foraminifera is therefore a climate indicator. Sediments are sampled by coring: with depth through a core, there are alternating periods of high and low 18O values. Warm stages are labelled with odd numbers and cold ones with even numbers. Smaller fluctuations within these are usually given letters (e.g. 5a, 5c and 5e are warm peaks in Stage 5, while 5b and 5d are the cold troughs).

The dating of oxygen isotope records was initially achieved by the use of RADIOCARBON DATING on organic material in the top 30,000 years of the sediment core and by identification of the Brunhes-Matuyama polarity reversal at 730,000

years (see PALAEOMAGNETIC DATING); prior to the development of URANIUM SERIES DATING, in-

terpolation between these assumed a constant sedimentation rate.

The timescale is now based on orbital forcing of climate, i.e. calculation of the effect on climate of changes in the earth’s orbit with time, in turn caused by changes in gravitational pull with changing configuration of the planets. The orbital parameters are eccentricity (the degree to which the orbit is ellipsoidal, the period of relevance being 100,000 years), tilt (the angle between the equatorial plane and the orbital plane, the period of relevance being approximately 41,000 years) and precession (the wobble in the rotation about the earth’s axis, the average period being 22,000 years). The recognition of all of these periods in the oxygen isotope record was the key factor in the acceptance that climate is controlled by changes in the earth’s orbit.

Correlation with the terrestrial climatic record has been clearly demonstrated for the long LOESS sequences of China where alternating warm and cold periods are represented by PALAEOSOLS and loess layers respectively; pollen sequences in coastal sediments have also been used. For other sites, where the record is discontinuous, correlation is assumed and assignment of a particular series of layers to isotope stages depends on the particular combination of climatic indicators and age indicators found in those layers (e.g. flora, fauna, geomorphology, absolute dates).

N.J. Shackleton: ‘Oxygen isotope analyses and Pleistocene temperatures re-assessed’, Nature 215 (1967), 15–17;

452 OXYGEN ISOTOPE CHRONOSTRATIGRAPHY

–––– and N.D. Opdyke: ‘Oxygen isotope and palaeomagnetic stratigraphy of equatorial Pacific core V28–238: oxygen isotope temperatures and ice volumes on a 105 year and 106 year scale’, Quaternary Research 3 (1973), 39–55; J.D. Hayes, J. Imbrie and N.J. Shackleton: ‘Variations in the earth’s orbit: pacemaker of the ice ages’, Science 194 (1976) 1121–32; J. and J.Z. Imbrie: ‘Modeling the climatic response of orbital variations’, Science 207 (1980), 943–53; F.C. Bassinot et al.: ‘The astronomical theory of climate change and the age of the Brunhes-Matuyama magnetic reversal’, Earth and Planetary Science Letters 126 (1994), 91–108.

SB

Ozette Village site of the Makah Indians, situated on the Washington coast of western North America, dating to c.AD 1450–1950. The village was covered by catastrophic mud slides while still occupied, resulting in the preservation of wooden tools, baskets, blankets and sculpture. David Huelsbeck (1988) quantified food resources, on the basis of ethnographic analogy and actual faunal remains, in an attempt to determine whether the surpluses attested ethnographically are detectable archaeologically. Detailed spatial analyses of variations in shellfish assemblages within, between and outside houses have provided data from which inferences can be made regarding social status and resource ownership (Wessen 1988).

R.D. Daugherty and J. Friedman: ‘An introduction to Ozette art’, Indian art traditions of the Northwest Coast, ed. R.L. Carlson (Burnaby, 1983), 183–98; D.R. Huelsbeck:

‘The surplus economy of the Central Northwest Coast’,

Research in economic anthropology (London, 1988), 149–78; G.C. Wessen: ‘The use of shellfish resources on the Northwest Coast: the view from Ozette’, Research in economic anthropology, ed. B.L. Isaac (London, 1988), 179–210; S.R. Samuels, ed.: House structure and floor midden: Ozette Archaeological Research Reports 1 (Pullman, 1991).

RC

Ozieri culture Farming culture of the Late Neolithic and Eneolithic of Sardinia, identified from excavations at the cave of San Michele near Ozieri. The pottery is finely made, often slipped or burnished, and is typically decorated with impressed or incised, and sometimes filled or hatched, concentric curvilinear or geometric designs. The Ozieri culture produced schematic marble figurines (e.g. that from Senorbí) which have been compared to the famous CYCLADIC examples, as well as figurines (e.g. that from Macomer) in a contrasting ‘naturalistic’ style. Perhaps the most distinctive late Ozieri creations are the multi-roomed, decorated rock-cut tombs, found singly or in cemeteries, such as ANGHELU RUJU, where Ozieri pottery is found in association with bell BEAKERS.

M. Guido: Sardinia (London, 1963); D.H. Trump: ‘The Bonu Ighinu Project and the Sardinian Neolithic’, Studies in Sardinian Archaeology I, eds. M.S. Balmuth and R.J. Rowland, Jr. (Ann Arbor, 1984), 1–22.

RJA

P

pa Earthwork forts of varying size and complexity mainly found in the North Island of New Zealand. Some were defended food stores, whereas others have convincing evidence of intensive occupation. There are estimated to have been 6000 pa, most of which were constructed in the last 600 years.

G. Irwin: Land, pa and polity (Auckland, 1985). J. Davidson: The prehistory of New Zealand (Auckland, 1984).

CG

Pachacamac Site of an important oracle and centre of a major variant of the HUARI religion and art style in central coastal Peru from the Middle Horizon period to the Conquest (c.AD 550–1500). It became a large urban centre in the Middle Horizon (c.AD 550–900), dwindled to a ceremonial centre with the Huari collapse, but remained important enough for the Inca to consult the oracle and to build an ACCLLAHUASI and a major temple to the sun at the site.

M. Uhle: Pachacamac (Philadelphia, 1991) [reprint of the 1903 edition of the book with a new introduction by Izumi Shimada].

KB

Paiján The earliest cultural group identified in Peru and one of the few PALEO-INDIAN traditions to have direct association with extinct fauna (La Cumbre site). A series of inland workshop sites (about 15 km from the northern coast of Peru) show the process of fabrication of the characteristic tool, the ‘Paiján point’ (a long, narrow tanged point apparently used for fishing), from a block to a bifacial blank to the point itself. Other tools and faunal remains show a mixed economy based upon fishing large species, shore-line collecting and fishing, and land hunting.

C. Chauchat: Préhistoire de la côte nord du Pérou: le Paijanien de Cupisnique (Paris, 1993).

KB

Painted Grey Ware (PGW) Widespread ceramic type in southern Asia, found at over 450

early Iron Age sites in the Indo-Gangetic Basin between c.1300 and 600 BC (although the chronology is controversial, see Lal 1980). The wheel-made ceramics (mainly bowl and dish forms) are thin, extremely well-made and uniformly fired, with a variety of black-painted motifs, including swastikas, spirals, lines and circles. PGW vessels typically comprise only 7–10% of a site’s total ceramics; they are associated with the appearance of iron in the Ganges basin (Lal 1984: 61) and Makhan Lal, Bal Krishen Thapar and others have suggested that the introduction of iron and PGW ceramics resulted from movement of population into the Ganges region from Iran and Central Asia (Lal 1984: 66). The inhabitants of PGW sites were small-scale agriculturalists and herders, living in riverside settlements (about 1.7–3.4 ha in size) such

as Ahichhatra, ATRANJIKHERA, HASTINAPURA,

Mathura and Noh. See figure 40 overleaf.

V. Tripathi: The Painted Grey ware: an Iron Age culture of northern India (Delhi, 1976); M. Lal: ‘Date of Painted Grey Ware culture: a review’ Bulletin of the Deccan College Research Institute 39 (1980), 65–77; ––––: Settlement history and rise of civilization in the Ganga-Yamuna Doab

(Delhi, 1984), 55–66; ––––: ‘The early settlement pattern of the Painted Grey Ware culture of the Ganga Valley’,

Recent advances in Indo-Pacific prehistory, ed. V.N. Misra and P. Bellwood (New Delhi, 1985), 373–81.

CS

Pai-Yüeh see YÜEH

Pakistan see ASIA, SOUTH

palaeofaeces see COPROLITES

Palaeolithic (‘Old Stone Age’) The first and longest division of the Stone Age, the Palaeolithic is essentially a technological classification starting with the products of the earliest toolmaking hominids, perhaps 2.5 million years ago, and ending with the onset of the Holocene in the 9th millennium BC and the technological changes that

454 PALAEOLITHIC (‘OLD STONE AGE’)

0 |

200 km |

||

|

|

|

|

Jullundur

Ludiana

Chandigarh

Amritsar

Saharanpur

|

|

|

|

|

ar |

|

|

|

|

g |

|

|

|

|

g |

|

|

|

|

a |

|

|

|

|

h |

|

|

|

|

. G |

|

|

|

|

|

R |

|

|

|

|

|

Suratgarh

Delhi

Gurgaon

Bikaner

Bharatpur

Jaipur

R. Luni .Chambal

R

Muzaffarnagar |

Nainital |

|

|

|

||

Bijnor |

N |

|

|

|

||

Meerut |

|

|

E |

P |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

A |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

L |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Bulandshahar |

|

|

|

|

||

Aligarh |

|

R. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

G |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

a |

|

|

|

|

|

|

n |

|

|

|

|

|

|

g |

|

|

|

|

|

|

a |

|

|

|

|

|

Etah |

Bahraich |

|

|

|

|

R |

|

Mainpuri |

Gonda |

|

|

|

. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Yamuna |

Lucknow |

Basti |

Gorakhpur |

|

|

|

|

Kanpur |

R. |

Ghaghara |

|

|

|

|

G |

|||

|

|

|

R |

R |

|

|

|

|

|

. |

. |

|

|

|

|

|

Sai |

o |

|

|

|

|

|

|

m |

|

|

|

|

|

Fatehpur |

|

a |

|

|

|

|

|

i |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

t |

|

Banda

Allahabad

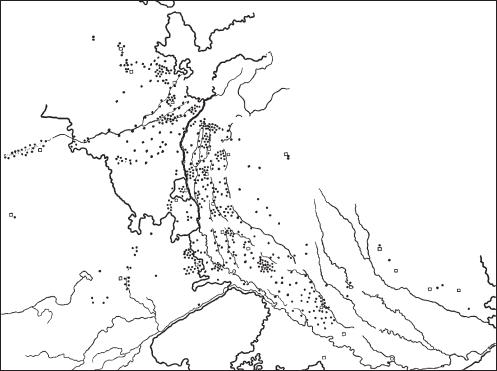

Figure 40 Painted Grey Ware Map showing the distribution of Painted Grey Ware in the Ganga Valley region of India. Source: M. Lal: ‘The settlement pattern of the Painted Grey Ware culture of the Ganga valley’, Recent advances in Indo-Pacific prehistory, ed. V.N. Misra and P. Bellwood (New Delhi, 1985), fig. 1.

characterize the succeeding MESOLITHIC period. Although originally defined with reference to stone industries alone, the term Palaeolithic came to imply a hunting and gathering economy and various cultural characteristics. Traditionally, it is divided into the Lower and Middle Palaeolithic (treated

here), and the UPPER PALAEOLITHIC.

The Lower Palaeolithic begins with the first stone tools produced by hominids (found in layers classified by geologists as Early to Middle Pleistocene), from the simplest flake tools of the Oldowan industries around 2.5 million years ago to the relatively crude bifacial handaxes made from perhaps 1.5 million years ago until about 250,000 years ago. The Oldowan flake industries are associated first with HOMO HABILIS, and then with various early hominids that make up the story of HUMAN EVOLUTION. The later tool industries of the Lower Palaeolithic, characterized by roughly symmetrical bifacial handaxes and cleavers, seem to be linked to the appearance of and

are also associated with later Homo Sapiens. These later industries are often grouped together and termed ‘ACHEULEAN’ – the term is a badge for industries of the same general level of technology, and does not imply cultural connections.

From perhaps 250,000 years ago, and particularly from after 150,000 years ago, the more advanced tool-making that involved preparation of cores and greater skills in design appeared – notably the use of the LEVALLOIS TECHNIQUE. At the same time, heavier handaxes tend to disappear from assemblages. According to traditional terminology, this technological change marks the beginning of the Middle Palaeolithic, and is closely associated with the early forms of Homo sapiens and especially with NEANDERTHALS (rather before 100,000 BP to 35,000 BP). A key industry of this type is the MOUSTERIAN tradition, first recognized at the French site of Le Moustier. Some archaeologists associate these more advanced tool assemblages with a shift in human capabilities, notably in terms