A Dictionary of Archaeology

.pdfPortuguese site of Dambarare, Rhodesia’. Proceeding and Transactions Rhodesia Scientific Association 54 (1969), 23–61.

TH

positive feedback see SYSTEMS THEORY

positivism Philosophy of science developed from the early 19th century that influenced the ‘New Archaeologists’ of the 1960s (see PROCESSUAL ARCHAEOLOGY). Set in train by the early French social scientist and thinker, Auguste Comte (1798–1857), positivism described an approach to truth-seeking that set aside simple hypothesizing and metaphysical discussion of the ‘inner essences’ and motivations that gave rise to social phenomena, in favour of careful observation and experiment regarding how social phenomena manifested themselves and related to each other in the real world. This essentially EMPIRICAL approach to understanding society may originally have been a reaction against the intellectual anarchy of revolutionary and post-revolutionary France (and the resulting social and political chaos), which seemed inferior to the explanations of the natural world as revealed by the methodologies of the physical sciences in the 18th and early 19th century. Positivism informed the much more rigorously formulated LOGICAL POSITIVIST movement in the early 20th century, and it was partly through the aims and methodologies of this (now defunct) school of philosophy that it influenced processual archaeology.

C. Hempel: Aspects of scientific explanation (New York, 1965).

RJA

post-depositional theory One of the five bodies of theory postulated by David Clarke in 1973 (published as Clarke 1979: 83–103). Whereas predepositional and depositional theory are primarily concerned with the establishing of links between individual human activity, social practices and the environment, as well as the exploration of connections between these phenomena and the archaeological record, post-depositional theory is concerned with the many influences that are brought to bear on the archaeological record, such as the ploughing of fields, the looting of tombs or the effects on the soil of freezing and drought. It is therefore broadly similar to the ‘N-TRANSFORMS’ of

Michael Schiffer’s BEHAVIORAL ARCHAEOLOGY,

while pre-depositional and depositional theory equate with his ‘C-TRANSFORMS’.

D.L. Clarke: Analytical archaeologist (New York, 1979);

POST-PROCESSUAL ARCHAEOLOGY 475

D.T. Nash and M.D. Petraglia, eds: Natural formation processes and the archaeological record. BAR IS 352 (Oxford, 1987).

IS

posthole (American: ‘postmold’) Small manmade pit visible as a smudge on the surface of an archaeological deposit, where a wooden post has once been pushed into the ground surface. Usually the decayed remains of the wood enable the posthole to be differentiated from the surrounding deposit. Several long-term experiments were carried out at the Princes Risborough Laboratory of the Building Research Establishment in the 1970s in order to determine the rates of decay of posts made from different types of wood (see Morgan 1975; Barker 1982: 89–91). At some sites, such as the Romano-British town of Wroxeter, large areas of settlement have been mapped almost entirely on the basis of postholes. See also STAKEHOLES.

J.W. Morgan: ‘The preservation of timber’, Timber Grower 55 (1975); P. Barker: Techniques of archaeological excavation 2nd edn (London, 1982), 77–94, 254–67, figs 23–5, 31.

IS

post-medieval archaeology see EUROPE,

MEDIEVAL AND POST-MEDIEVAL 2

post-positivism see POST-PROCESSUAL

ARCHAEOLOGY

post-processual archaeology Any attempt to reach a satisfactory definition of this body of archaeological theory is frustrated by the fact that, as its name implies, it is a disparate set of approaches united only by a sense of revolt against the domination of the subject by PROCESSUAL,

FUNCTIONALIST and POSITIVIST theory. The term

post-processual archaeology was coined by Ian Hodder in 1986 in the first edition of Reading the past (see Hodder 1991, the second edition), and is now usually taken to encompass approaches

such as CONTEXTUAL ARCHAEOLOGY, CRITICAL ARCHAEOLOGY, CRITICAL THEORY, FEMINIST ARCHAEOLOGY, MARXISM, PHENOMENOLOGY and

POST-STRUCTURALISM.

For many archaeologists, the movement is exemplified by two books published in 1987, in which Michael Shanks and Chris Tilley sought to overturn many of the sacred cows of a ‘New Archaeology’ that had ceased to be radical or revisionist and which, by the 1980s, had itself

476 POST-PROCESSUAL ARCHAEOLOGY

become very much the established approach in the discipline. Shanks and Tilley (1987b) argue that IDEOLOGY – consciously or unconsciously – informs virtually all archaeological description and interpretation, and that there is no truly objective set of data or conclusions, given that all approaches are inevitably coloured by ideological biases and constraints. Furthermore, not even the awareness of such self-limitations can relieve archaeologists of their ideological baggage – an argument that is founded in the concerns of POSTSTRUCTURALISM. The solution put forward forcefully by Shanks and Tilley is the adoption of a combination of relativism and CRITICAL THEORY, whereby, instead of striving for an unattainable set of archaeological ‘truths’ or ‘facts’, archaeologists should pursue self-consciously ideologically informed approaches to their data, in other words: ‘polemic and rhetoric should be an essential part of archaeological text production to stimulate the reader to be a producer of the text’s meaning and its relation to the meaning of the past, not a passive consumer of a bland and smooth narrative . . .

inviting acquiescence rather than critical reflection’ (1987b: 207). One of the most recent manifestations of post-processual archaeology is ‘interpretive archaeology’ (see, for instance, Tilley 1994).

M. Shanks and C. Tilley: Re-constructing archaeology (London, 1987a); ––––: Social theory and archaeology

(Cambridge, 1987b); B.G. Trigger: A history of archaeological thought (Cambridge, 1989), 348–57; I. Hodder: Reading the past, 2nd edn (Cambridge, 1991), 156–81; N. Yoffee and A. Sherratt, eds: Archaeological theory: who sets the agenda? (Cambridge, 1993); C. Tilley, ed.: Interpretative archaeology (Oxford, 1994) [see review: I. Hodder, CAJ 5/2 (1995), 306–9]; I. Hodder et al., eds:

Interpreting archaeology; finding meaning in the past

(London, 1995); R.W. Preucel and I. Hodder, eds:

Contemporary archaeology in theory: a reader (Oxford, 1996).

IS

post-Shamarkian see SHAMARKIAN

post-structuralism Intellectual movement that emerged in several disciplines during the 1960s as a reaction against – and development of – STRUCTURALISM. The essence of post-structuralism is that it stressed the ‘significatory’ nature of linguistic and cultural constructions. If, as the Swiss linguist Ferdinand de Saussure originally explained, words and other signs were linked in only an arbitrary way to the external world, and gained meaning largely through their relationship with other signs, then cultural ‘texts’ had to be

analysed largely by reference to meanings within themselves (and, perhaps, within the mind of the reader of the text).

This contrasted with many structuralist analyses

– for example, the work of Lévi-Strauss (see STRUCTURALISM) – which examined structures in cultural communications as a way of illuminating society itself, and which often searched for universal laws and truths. Post-structuralist critiques proclaimed the autonomy of the cultural text from the social context that had produced it, and focused instead on meaning relationships within the individual text and the mind of the reader. The autonomous text was no longer explained by, or important because of, its relationship with ‘real’ social phenomena.

Post-structuralists criticized the ‘scientific’ approach of structuralism, which had led to overdependence on simplistic notions such as binary oppositions. Leading post-structuralist thinkers included the French theorist Jacques Derrida, who stressed for example that the meaning of a word arises from past uses in other texts and contexts, and cannot be understood simply by analysing its formal position within a system of structures. Derrida also insisted that the reader or speaker of a text played equal part in giving the text meaning: speech should not be privileged over writing, and writer should not be privileged over reader. Derrida denied that a ‘final’ meaning of any text could be discovered: instead the post-structuralist critic’s deconstruction of the text offered only one account of (or interaction with) its possible meanings. Careful analysis of the meaning structures within a text could lead a text to deconstruct and thus ‘subvert’ itself. But there was no final objective truth, simply an ever-evolving set of insightful interpretations. The French philosopher-historian Michel Foucault (1926–84) hugely influenced poststructuralist thought in the 1970s, stressing that communicated knowledge is structured into ‘discursive formations’, and therefore helps to shape society and social institutions.

The intellectual currents summarized above can be seen as influences on various approaches in archaeology. In particular, the antagonism to positivism and the certainties of science, the stress placed on reflexive modes of thought, and the idea of the reader as active rather than passive, surface as powerful features of Ian Hodder’s influential

CONTEXTUAL ARCHAEOLOGY. This and other

approaches that developed in archaeology in the late 1970s and early 1980s came to be bundled together as POST-PROCESSUALIST rather than poststructuralist, partly because the processual

approach in archaeology (particularly North American archaeology) dominated the discipline much more than structuralist approaches – the intellectual reaction was thus overtly ‘antipositivist’ rather than ‘anti-structuralist’ – but also because early post-processualist theorists in archaeology did not adopt a fully post-structuralist stance.

Just as post-structuralist approaches in literary criticism and sociology led some writers to conclude that finding objective truths about texts or social institutions was an impossible (or endless) task, so post-structuralist approaches in archaeology suggested to some that objective provable knowledge of past societies is also unattainable. The complexities of deconstruction were rarely attempted as a mode of analysis of archaeological evidence, but the intellectual rhetoric gave a powerful prop to those who sought to counter the bold attempts by processualist archaeologists to formulate and apply general laws.

For some time, the language of poststructuralism was clearly visible in the dialectic between processualists and post-processualists, but it seemed that the discipline would be spared a concerted attempt to build a ‘post-structuralist’ archaeology. In the early 1990s, however, a series of texts (e.g. Bapty and Yates 1990; Baker and Thomas 1990; Olsen 1990) adopted a much more radical post-structuralist stance. At the extreme, the idea that an archaeologist can or should attempt to reach the original meaning of an action that produced part of the archaeological text (i.e. the motive of the prehistoric ‘author’) is discounted. Archaeological data, like texts, are simply systems of structured differences, with arbitrarily assigned meanings that will be interpreted differently by different readers (even within the ancient society, let alone the modern society of the archaeologist). As a result, the possible interpretations of the archaeological text are endless, and it is impossible and, more importantly, fruitless, to attempt a single ‘objective’ interpretation of the past. It is the analysis of the subjective nature of the archaeological interpretation, rather than the ancient society itself, that is privileged.

Hodder (1992: 160–8), whose own work stresses the complexity of interpreting symbolism and material culture within past societies, rejects this extreme post-structuralist approach. He argues that in valuing the importance of present interpretation more highly than what it tells us about the past the archaeologist is in danger of undermining archaeology’s special purpose and value – and of disappearing into a quagmire of relativism. Instead, faced with the extreme version of ideas that he had

POTASSIUM-ARGON (K-AR) DATING 477

advanced more cautiously in his own CONTEXTUAL ARCHAEOLOGY, Hodder chooses to stress the ‘objectivity of the data’ – that is, inherent qualities within sets of archaeology data that help us to sort likelihoods from unlikelihoods (see also THEORY

AND THEORY BUILDING).

Post-structuralism, as a self-conscious intellectual approach, has faded away in most disciplines in which it was identifiable as a moving force in the 1970s and 1980s. In archaeology, poststructuralism in its purest but least ‘archaeological’ form may continue to be of interest as a way of criticizing archaeological texts themselves – of analysing the ways in which they structure meaning, and as a useful technique within the subdiscipline of historiography. In shaping approaches to primary archaeological material, it has had an unintended but perhaps more important effect: by making clear the destructiveness of extreme relativism, it has forced post-processualist archaeologists to consider again the nature of objectivity and truth in the discipline, and to realize that these concerns remain, whether or not it is the ambition of the archaeologist to construct universal laws.

F. Baker and J. Thomas, eds: Writing the past in the present

(Lampeter, 1990); I. Bapty and T. Yates, eds: Archaeology after structuralism (London, 1990); B. Olsen: ‘Roland Barthes: from sign to text’, Reading material culture, ed. C. Tilley (Oxford, 1990); C. Tilley, ed.: Reading material culture (Oxford, 1990); I. Hodder: Theory and practice in archaeology (London, 1992).

RJA

potassium-argon (K-Ar) dating Scientific dating technique, which, in archaeology, has mainly been used for dating volcanic deposits associated with early hominid remains in East Africa,

notably at OLDUVAI GORGE and KOOBI FORA. It

has also been the main technique used to establish the timescale of the geomagnetic reversal and oxygen isotope sequences (see

MAGNETIC DATING and OXYGEN ISOTOPE CHRONOSTRATIGRAPHY).

The principles of the technique lie in the decay of the 40K isotope of potassium, comprising 0.00117% of naturally occurring potassium. The half-life of 40K is 1250 million years. The decay product of interest is the stable 40Ar isotope of the gas argon, the probability of formation for which is 11.2%. As a first approximation it is assumed that, being a gas, the amount of argon in a rock on formation from the molten state is zero, and from this time the 40Ar builds up from decay of 40K. Also from this initial time, it is assumed that the system is closed to 40K and 40Ar i.e. their concentrations change only due to

478 POTASSIUM-ARGON (K-AR) DATING

radioactive decay and build-up respectively. The K-Ar age can then be determined by measurement of these concentrations. Total potassium can be readily determined by analytical techniques such as

ATOMIC ABSORPTION SPECTROPHOTOMETRY.

The 40Ar is measured, relative to a known amount of 38Ar, by mass spectrometry of the gas released on fusion by a separate sample.

If there has been reheating, recrystallization or weathering of the rock, or hydration or devitrification of glassy materials, the closed system assumption will be invalid. Another problem is incorporation of detrital material which can lead to high K-Ar ages. Dating of different mineral fractions will reveal these problems, as the ages will vary. The assumption of initial zero concentration of 40Ar is also problematic because atmospheric argon (typically 1% of the atmosphere) is usually incorporated by minerals as they cool. Fortunately this can be detected and corrected for using 36Ar which comprises about 0.34% of atmospheric argon. Incorporation during cooling of non-atmospheric 40Ar from the outgassing of surrounding rocks is more of a problem, but can be detected by the ARGON-ARGON technique.

Given the long half-life of 40K, the lower age limit of the technique is the constraint in archaeological applications. For minerals with a high potassium content, samples as young as 1000 years can be dated, but the error terms are high (typically ±100%). At 100,000 years, however, errors of ±5% are achievable, but these increase with decrease of the potassium content.

G. Faure: Principles of isotope geology, 2nd edn (New York, 1986); D.A. Richards and P.L. Smart: ‘Potassium-argon and argon-argon dating’, Quaternary dating methods – user’s guide, ed. P.L. Smart and P.D. Fraces (Cambridge, 1991), 37–44.

SB

Poverty Point Prehistoric site in northeastern Louisiana, along the western edge of the Mississippi River valley, which is the type site for the Poverty Point culture (c.1500–1000 BC). It consists of six large concentric semicircular earthworks with a maximum diameter of about 1200 m, several large earthen mounds, and an associated habitation area. The excavated artefacts include evidence of a welldeveloped lapidary technology in which exotic raw materials (such as jasper, steatite, fluorite and galena) were used to manufacture beads, plummets and pendants. Distinctively-shaped baked clay objects are also common. The presence of such a

wide array of exotic materials at the Poverty Point site has led some researchers to speculate that the site was a regional economic centre. More than 100 additional Poverty Point culture sites are known for the region.

J. Ford and C. Webb: Poverty Point: a late Archaic site in Louisiana (New York, 1956); R. Neuman: An introduction to Louisiana archaeology (Baton Rouge, 1984), 90–112.

RJE

Prasat Pram Loven (Plain of Reeds) Lowlying area near the Mekong Delta in Vietnam, where an important early Sanskrit inscription was found. It records that Gunavarman consecrated a footstep of Visnu, and also that this prince was sent to the area to reclaim marshland. G. Coedes has dated the text on stylistic grounds to the 6th century AD, and the reference to drainage recalls the extensive network of canals found in this area which provided not only transport and communication, but also the control by drainage of the annual Mekong floods.

G. Coedes, ‘Deux inscriptions Sanskrites de Fou-nan’, BEFEO 31 (1931) 1–23.

CH

precision In the statistical analysis of archaeological DATA, the precision of a PARAMETER ESTIMATE indicates how close it is likely to be to the true value, for example the ± of a RADIOCARBON DATE indicates how close to the quoted date the true date is likely to lie. The STANDARD DEVIATION of the estimate is often used to express this. It should not be confused with the accuracy of an estimate, which is the actual difference between it and the true mean, and is usually unknown.

CO

pre-depositional theory see BEHAVIORAL

ARCHAEOLOGY; C-TRANSFORMS; POSTDEPOSITIONAL THEORY

prehistoric Term used since the mid-19th century to indicate the period of human history before writing was invented or (in most cases) introduced into a region. The complex etymology of the term is discussed by Clermont and Smith (1990).

N. Clermont and P. Smith: ‘Prehistoric, prehistory, prehistorian . . . who invented the terms?’, Antiquity 64 (1990), 97–102.

RJA

Pre-Pottery Neolithic |

see ACERAMIC |

NEOLITHIC |

|

Pre-Sargonic period |

see EARLY DYNASTIC |

PERIOD (MESOPOTAMIA) |

|

pressure flaking Technique for retouching flint by applying pressure to the edge of a flake, using a pressure flaking tool (often of bone, antler or wood), rather than by striking the flake. Pressure flaking allows a much greater degree of precision and enables skilled flint knappers to detach regular flat flakes. Experimental work suggests that some knappers in the Upper Palaeolithic were preheating flints in hearths to make the material more amenable to pressure flaking.

RJA

prey-choice model see FORAGING THEORY

primary silt, primary fill, rapid silt Term used to describe the debris (comprising silt, scree and fallen turf) which accumulates at the bottom of a freshly dug ditch, usually taking about a decade or two to form. Once the ditch has become somewhat wider and shallower, a ‘secondary silt’ forms over the top of the primary deposit.

principal components analysis (PCA) A

branch of MULTIVARIATE STATISTICS which rep-

resents multivariate archaeological DATASETS (for example the results of analysing a set of artefacts for a series of chemical elements) by a SCATTERGRAM in two dimensions, accompanied by related useful statistics. The principal components are combinations of the original VARIABLES, and represent a rotation of the original space to better show the pattern of the points in it. The first axis of such a plot is the first principal component of the dataset, i.e. the axis which achieves the greatest possible dispersion of the points when they are plotted along it. The second axis is the one at right angles to the first which achieves the greatest possible dispersion not already accounted for by the first, and so on. It is a useful

technique of EXPLORATORY DATA ANALYSIS (EDA),

provided that the variables are all continuous and can be measured on the same scale. If the variables are measured on different scales, it may still be possible to use PCA, provided the data are first

STANDARDIZED.

J.E. Doran and F.R. Hodson: Mathematics and computers in archaeology (Edinburgh, 1975), 190–7; C.R. Orton:

PROCESSUAL ARCHAEOLOGY 479

Mathematics in archaeology (Glasgow, 1980), 56–62; S. Shennan: Quantifying archaeology (Edinburgh, 1988), 245–70; M.J. Baxter: Exploratory multivariate analysis in archaeology (Edinburgh, 1993).

CO

probabilistic approach see COVERING LAWS

probability In classical statistics, the probability that a VARIABLE takes certain values is the proportion of occasions in which it would take those values in a large number of repeated experiments or SAMPLES. For example, the probability that a single transect of a field survey would cross a certain site is the proportion of all the possible but hypothetical transects that would cross the site. Partly in response to the difficulty of applying this definition to situations in which repeated sampling is not possible, e.g. in taking RADIOCARBON DATES, BAYESIAN STATISTICS were developed, in which the interpretation of probability is subjective – a researcher’s degree of belief that a variable will take certain values.

J.E. Doran and F.R. Hodson: Mathematics and computers in archaeology (Edinburgh, 1975), 30–71; C.R. Orton:

Mathematics in archaeology (Glasgow, 1980), 219–20.

CO

processual archaeology Approach which was adopted by many American and some western European archaeologists during the 1960s and 1970s, formally beginning with the argument set out by Kent Flannery (1967) that ‘culture process’ (rather than ‘CULTURE HISTORY’) was the true aim of archaeological research. Whereas culturehistorical archaeologists, such as Gordon Childe and Gordon Willey, had been concerned primarily with the transformation of archaeological data into prehistoric narratives, Flannery suggested that the archaeologist ought to be seeking out the basic systems or predictable sets of laws and mechanisms (e.g. geological, ecological or social) which brought into existence the constituents and patterns of the archaeological record.

The practitioners of archaeology since its beginnings had been mainly educated in classics and history, whereas the so-called ‘New Archaeology’ of the 1960s opened the field up to the methods and theory of geography, sociology and the information sciences. A key feature of processual archaeology as practised was the use of quantitative methods to analyse features and patterns within the archaeological record (see, for instance, SPATIAL ANALYSIS). Evidence was presented in a more ‘scientific’ style

480 PROCESSUAL ARCHAEOLOGY

with much greater use of graphs, diagrams, flow charts, and schematic plans and maps. The focus of investigation shifted towards questions that involved ‘harder’ or more scientifically accessible data such as economy, settlement hierarchies, population densities, materials analysis etc., and away from attempts to understand the motivation of individuals or interpret evidence in ‘nonfunctional’ ways. Rather than simply presenting archaeological interpretation as self-evident, or as a plausible narrative full of insightful ideas, archaeological theses and reports were increasingly constructed so as to clarify the links between statement and evidence.

At a more philosophical level, the idea of the archaeological site as a means of obtaining one or more cultural ‘snapshots’ from within a long historical sequence, was to be replaced by the sense that every artefact or assemblage was part of some form of pattern that could be scientifically decoded if the archaeologist could only determine the universal laws governing site formation processes, cultural factors or ecological determinants. The nature and identity of such laws could be investigated not only by the traditional techniques of survey and excavation, but also by such methods as

ETHNOARCHAEOLOGY, ACTUALISTIC STUDIES and EXPERIMENTAL ARCHAEOLOGY.

There were initially at least two strands of New Archaeology, consisting of the ANALYTICAL ARCHAEOLOGY of the British archaeologist David Clarke and the processual and FUNCTIONALIST approaches being set out by Lewis Binford. Whereas Clarke’s approach was primarily concerned with the different ways of interpreting archaeological remains (particularly the use of statistics), Binford began to move gradually away from traditional archaeological data, pursuing instead the kinds of ethnographic information that could serve as links and analogues between ancient and modern material cultures. This project underlined the POSITIVIST nature of the New Archaeology, and drew on the

approach to knowledge gathering that characterized the LOGICAL POSITIVIST project. By making explicit and testing a body of theory (Binford’s ‘MIDDLE-RANGE THEORY’) that linked archaeological data and low-level theorizing more securely to interpretation of human behaviour at archaeological sites, the New Archaeologists hoped to build a platform of secure statements about the past from which they could infer and test general theories about social dynamics. Although many processual archaeologists held that their ultimate aim was the construction of a body of general theory, the most

characteristic and contentious part of the project turned out to be the creation of reliable and useful middle-range theory. Michael Schiffer’s BEHAVIORAL ARCHAEOLOGY, conceived as a critique of simplistic interpretations of patterning in the archaeological record, was probably the most ambitious attempt to lay down a set of rules governing the processes of site formation and cultural development. The approaches adopted by Flannery, Clarke, Binford, Schiffer and many other processual archaeologists had much in common, but at the time there were many very public arguments concerning such issues as the validity or relevance of the approach. Perhaps the only real consensus among the most vocal proponents of processual archaeology was the sense that there could be no return to culture history.

Since the early 1980s, the cruder versions of processual archaeology have been increasingly criticized for their tendency towards determinism of various sorts as well as the occasional predilection for ‘number-crunching’ as an end in itself. Ian Hodder (1991: xiv) has pointed out that this propensity has, if anything, been accentuated by the methods of funding archaeology, in the 1990s, which have become increasingly geared towards science-based projects, thus threatening to ‘nudge archaeology not towards a fruitful integration with science . . . but towards a narrow scientism’. It was primarily in reaction to this perception of processual archaeology as an attempt by archaeologists to ape ‘real scientists’ that the

earliest exponents of POST-PROCESSUAL ARCHAE-

OLOGY (Shanks and Tilley 1987a; 1987b; Hodder 1991) set out their more humanistic, subjective and ‘self-critical’ approaches to the interpretation of the past.

Renfrew and Bahn (1991: 405) suggest that

COGNITIVE ARCHAEOLOGY should be regarded as a

further development of the processual school rather than a reaction against it. They thus make a distinction between the earlier ‘functionalist processual’ approaches characterized by the work of Schiffer and Binford in the 1970s and 1980s, contrasting these with the ‘cognitive-processual’ approaches of the late 1980s and 1990s (e.g. Renfrew and Zubrow 1994).

See CARTER RANCH PUEBLO for a discussion of the emergence of processual archaeology in America, particularly with regard to the study of social organization.

K.V. Flannery: ‘Culture history v. culture process: a debate in American archaeology’, SA 217 (1967), 119–22; L.R. Binford: ‘Some comments on historical versus processual archaeology’, SJA 24/3 (1968), 267–75; D.L.

Clarke: Analytical archaeology (London, 1968); P.J. Watson: ‘Archaeological interpretation, 1985’, American archaeology: past and present, ed. D.J. Meltzer, D.D. Fowler and J.A. Sabloff (Washington, D.C., 1986); T.K. Earle and R.M. Preucel: ‘Processual archaeology and the radical critique’, CA 28 (1987), 501–38; M. Shanks and C. Tilley: Re-constructing archaeology (London, 1987a); ––––

and ––––: Social theory and archaeology (Cambridge, 1987b); R. Preucel, ed.: Between past and present: issues in contemporary archaeological discourse (Carbondale, 1990); I. Hodder: Reading the past 2nd edn (Cambridge, 1991); C. Renfrew and P. Bahn: Archaeology: theories, methods and practice (London, 1991); C. Renfrew and E.B. Zubrow, eds: The ancient mind: elements of cognitive archaeology

(Cambridge, 1994).

IS

Proconsul see RUSINGA

profile Vertical section that can be used to view both the stratigraphy and the horizontal relationships of the various natural and cultural features making up an archaeological site. The term is also used to refer to drawings of such sections.

Prolonged Drift Waterside Late Stone Age site located in ELMENTEITA, in the elevated stretch of the Kenya Rift Valley; it lies on or adjacent to a site previously called ‘Long’s Drift’ by Louis Leakey: hence the jocular nomenclature. Prolonged Drift was investigated by Glynn Isaac, Charles Nelson and colleagues in the late 1960s. The faunal remains, analysed by Diane Gifford-Gonzalez (Gifford et al. 1980), provide an important model for reconstructing the economy and ecology of later African hunter-gatherers and early (‘Neolithic’) pastoralists.

D.P. Gifford, G.Ll. Isaac and C.M. Nelson: ‘Predation and pastoralism at Prolonged Drift: a Pastoral Neolithic site in Kenya’, Azania 15 (1980), 57–108.

JS

Protogeometric see GEOMETRIC AND

PROTOGEOMETRIC

Protoliterate period The earliest historical phase in the history of SUMER, defined by Frankfort (1970: 381) as comprising most of the URUK period and the whole of the JEMDET NASR period, when Sumerian writing and art were both emerging in Mesopotamia.

H. Frankfort: The art and architecture of the ancient Orient, 4th edn (Harmondsworth, 1970).

PUEBLO BONITO 481

Protosinaitic Early alphabetic script of the mid-2nd millennium BC, discovered in the form of rock-carved inscriptions at Egyptian mining sites in the Sinai peninsula (particularly

KHADIM).

W.F. Albright: The Protosinaitic inscriptions and their decipherment (Harvard, 1966); W.V. Davies: Egyptian hieroglyphs (London, 1987), 57–61.

IS

proxemics Study of the spatial aspects of human social interaction.

Pucara Large urban site in southern Peru, which was occupied for a single period from 100 BC to AD 100. The religious art features a female deity with a llama and a warrior with feline characteristics, trophy heads, incised polychrome ceramics with mythic figures, and full round stone sculptures of humans and deities; these artistic features were extremely influential on contemporary cultures of the altiplano and northern Chile. The settlement is built of adobe upon stone foundations, and the major structure is a U-shaped temple with stone cist tombs in the courtyard.

A.L. Kidder: Some early sites in the northern Lake Titicaca Basin (Washington, D.C., 1943); S.J. Chávez: ‘Archaeological reconnaissance in the province of Chumbivilcas, South Highland Peru’, Expedition 30/3 (1988), 27–38.

KB

pueblo (Spanish: ‘village’) Term used to describe the historic stone-masonry or adobe-built settlements of the American Southwest, such as the ANASAZI town, PUEBLO BONITO. Each pueblo consists of many rooms, often several storeys in height.

JJR

Pueblo Historical and present-day cultural group in the American Southwest, who are thought to be the descendants of the prehistoric ANASAZI, MOGOLLON and HOHOKAM groups. The term is also used to describe the five latest phases in the Anasazi chronological sequence, from c.AD 700 to the present.

E.P. Dozier: The Pueblo Indians of North America (New York, 1970).

JJR

Pueblo Bonito Located in Chaco Canyon, northwestern New Mexico, Pueblo Bonito is the most famous ANASAZI pueblo in the American

482 PUEBLO BONITO

Southwest. Consisting of 800 rooms, 60 kivas, three great kivas and two platform mounds, it was inhabited throughout the Pueblo II period (AD 900–1150) and was the centrepiece of the CHACO culture.

S.H. Lekson: Great Pueblo architecture of Chaco Canyon, New Mexico (Albuquerque, 1986); S.H. Lekson, T.C. Windes, J.R. Stein and W.J. Judge: ‘The Chaco Canyon community’, Science 259 (1988), 100–109; R.G. Vivian:

The Chacoan prehistory of the San Juan Basin (New York, 1990).

JJR

Puerto Hormiga, Monsú and San Jacinto

Group of sites on the Caribbean littoral near Cartagena in northern Colombia, dating from 3800 to 3300 BC, which have yielded the earliest welldated ceramics in the Americas. Puerto Hormiga and Monsú are shell mounds, and San Jacinto is a seasonal camp site where plants were roasted in pits. The ceramic assemblages from all three are technically and aesthetically complex, but bear little resemblance to each other. There is no evidence of either agriculture or the use of ceramics in cooking.

G. Reichel-Dolmatoff: ‘The cultural context of early fiber tempered pottery in Colombia’, The Florida Anthropologist

25/2 (1972), 1–2; ––––: Monsú: un sitio arqueológico

(Bogotá, 1985); C.A. Oyuela: ‘Dos sitios arqueológicos con desgrasante de fibra vegetal en la Serranía de San Jacinto’,

Boletín de Arqueología 2/1 (1987), 5–26.

KB

pulse theory Model put forward by Roderick McIntosh to account for the origins of urbanism in the Inland Niger Delta (IND) of Mali in the 1st millennium AD. It is assumed that this was an indigenous development, not dependent on the stimulus of outside trade, representing an elaboration of existing trends, not a revolutionary event. The model presupposes the interaction of three local factors – climatic, geomorphological and social

– which may have brought it about:

1 Climate. The climate of West Africa is in large part determined by the north–south movement (or ‘pulse’) of the InterTropical Convergence Zone (ITCZ). Annually, this causes the alternating dry and wet seasons which characterize the region; in addition, it is known that over millennia the position of the ITCZ has varied, periods of desiccation coinciding with its southerly displacement and vice versa. It was during a northern swing of the ITCZ that the IND will have been occupied, but the population will have been constrained by previous soil damage from following the pulse further north.

2 Geomorphology. The floodplain of the IND, how-

ever, constitutes a privileged area, a hydrological and landform labyrinth making up an ‘unusual geomorphological anomaly’, which provided a functionally advantageous setting for agricultural experimentation, population expansion, and the development of a clustered urbanism in which major settlements were surrounded by numerous satellites.

3 Society. This by itself was not sufficient, since the intensification of specialization demanded by a developing urbanism depended also on the elaboration of a shared ideology, which was achieved (and finds its echo today) in the pattern of settlement of the IND, where different ethnic groups pursue different subsistence occupations but are bound together by well recognized mutual obligations.

R.J. McIntosh: The pulse theory: genesis and accommodation of specialization in the inland Niger Delta of Mali (Houston, 1988).

PA-J

Punt East African region to which Egyptian trading missions were being sent from at least the early 3rd millennium BC. Scenes of Punt and its inhabitants are depicted on the second terrace of the Temple of Hatshepsut at DEIR EL-BAHARI (c.1460 BC). Many missions evident departed from the ports of Quseir or Mersa Gawasis on the west coast of the Red Sea, but there is still some dispute concerning the precise geographical location of Punt. It was once commonly considered to have been in the region of modern Somalia – Herzog (1968) even suggests an upper Nile location – but the fauna and flora depicted at Deir el-Bahari suggest that Punt was located in southern Sudan or the Eritrean region of Ethiopia (Kitchen 1971; 1993).

R. Herzog: Punt (Glückstadt, 1968); K.A. Kitchen: ‘Punt and how to get there’, Orientalia 40 (1971), 184–207; ––––:

‘The land of Punt’, The archaeology of Africa, ed. T. Shaw et al. (London, 1993), 587–608.

IS

Pushkalavati see CHARSADA

Puuc A subregion of LOWLAND MAYA culture, centred on the low Puuc hills in northwestern Yucatán. The region has given its name to a LateTerminal Classic (c.AD 800–1000) architectural style characterized by fine veneer masonry and elaborate mosaic facades. This is best seen on sites within the region, such as SAYIL, Labná and Kabáh, but also appears at CHICHÉN ITZÁ.

H.E.D. Pollock: The Puuc: an architectural survey of the hill

PYLON 483

country of Yucatan and northern Campeche, Mexico

(Cambridge, MA, 1980).

PRI

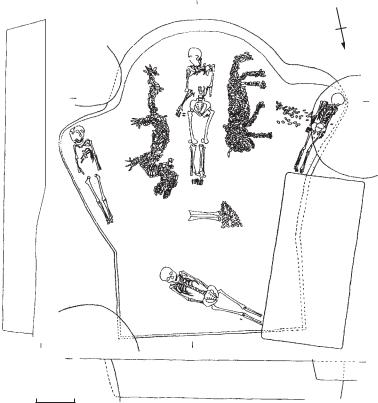

P’u-yang-shih (Puyangshi) Site of the YANGSHAO Neolithic culture, which was excavated in March, 1987, at Hsi-shui-p’o near the southwest corner of the city of P’u-yang, province of Ho-nan, China. It is remarkable for three groups of animal representations laid out with molluscan shells, one in Tomb 45 and the other two to the south of the tomb. The group in Tomb 45 comprised a dragon and a tiger; the second group, a dragon with a spider near its head, and a tiger on the back of which is a deer; the third group, a dragon with a man riding on its back, and again a tiger. The excavators considered that there was a ritual significance attending these, thus suggesting the possibility of a connection with the much later Taoism: in the Pao-p’u-tzu

of Ko Hung (c.AD 283–343) there are references to the san ch’iao: the dragon-ch’iao, the tiger-ch’iao, and the deer-ch’iao. Possibly the explanation of the frequently depicted ‘man-beast’ or alter ego motif throughout Chinese art from Shang times might also be sought here. Tomb 45 is therefore thought to have been that of a SHAMAN, together with his three travelling companions.

Anon.: ‘Ho-nan P’u-yang Hsi’shui-p’o yi-chih fa-chüeh pao’, WW 3 (1988), 1–6; D. Bulbeck, ed.: Ancient Chinese and Southeast Asian bronze cultures (Taipei, 1996).

NB

pylon (Greek: ‘gate’) Classical term for the Egyptian ceremonial gateway or bekhenet used in temples from at least the Middle Kingdom to the Roman period (c.2040 BC–AD 395), probably symbolizing the horizon. The basic structure of a pylon

M45

D’

0

H34

A

H51

A’

H34

30 cm

C

N

B

H46

M45

M54

D

B’

M46

M45

Figure 42 P’u-yang-shih P’u-yang ‘shaman tomb’ (no. 45), China, showing how concentrations of shells were arranged in the shapes of animals. Source: WW 3 (1988), fig. 5.

484 PYLON

consists of two massive towers of rubble-filled masonry tapering upwards, surmounted by a cornice and linked in the centre by an elaborate doorway. Ancient depictions of pylons show that the deep vertical recesses visible along the facades of surviving examples were intended to hold flag staffs.

T. Dombardt: ‘Der zweitürige Tempelpylon altägyptischer Baukunst und seine religiöse Symbolik’, Egyptian Religion 1 (1933), 87–98; P.A. Spencer: The Egyptian temple: a lexicographical study (London, 1984), 193–4.

IS

Pylos Mycenaean palace located on the hill at Ano Englianos in the Messenian plain, Greece. Together with the sites of MYCENAE and TIRYNS, it offers the most impressive evidence of the Mycenaean culture of the Greek Bronze Age. In contrast to these other sites, Pylos is completely

unfortified, and appears to have been the seat of a local chief or king. It was built during the Late Helladic IIIb pottery phase, indicating that it flourished during the 13th century BC, until being destroyed by fire. The complex centres on a MEGARON, consisting of a vestibule and portico leading in from a courtyard to a great ‘throne-room’ with hearth and frescoes, store-rooms (especially for olive oil), and a wine magazine. The walls are of rubble on the ground floor, with ashlar facades and fine plaster on the interiors. Other decoration includes painted and fluted columns, and fresco painting in the Mycenaean style (i.e. Minoan influenced, but conventionalized and less naturalistic). Upper stories are of mud brick, and the sophisticated design includes lightwells and a drainage system. Pylos is especially important because it contained an archive of Linear B script tablets; these represent a series of administrative records, naming 16 tributary localities in the Messenian plain.

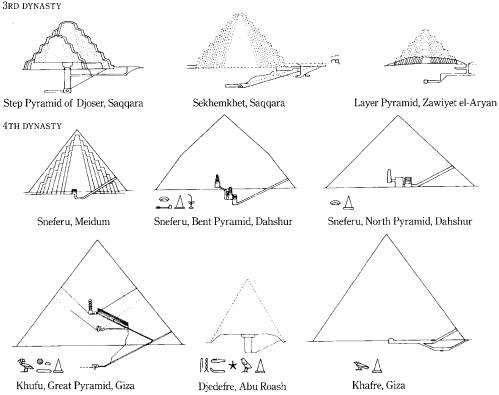

Figure 43 pyramid Cross-sections of the major pyramids built during the 3rd and 4th dynasties in Egypt, drawn to the same scale. Source: M. Lehner: The complete pyramids (Thames and Hudson, 1997), p. 16.