A Dictionary of Archaeology

.pdfcarbon dates (c.5000 BC) in the Cyclades. The series was the first to prove that settlements existed in the Cyclades long before the development of the Cycladic culture (from c.3300 BC). The Saliagos farmers grew barley and wheat and kept sheep and goats and some pigs; fishing was also very important. The village produced pottery decorated with white paint, and some simple flat marble figurines that strongly resemble the later ‘violin’ figurines of the Early Cycladic I culture; there is also a rather different figurine with massive rounded buttocks, irreverently called the ‘Fat Lady of Saliagos’.

J.D. Evans and C. Renfrew: Excavations at Saliagos near Antiparos (London, 1968).

RJA

Samarra Type-site of the prehistoric Samarra culture and major city-site of the early Islamic period.

1 Prehistory. The ‘Samarra culture’ appeared in the northern Mesopotamian plain and the ZAGROS region around the middle of the HASSUNA period (c.5600 BC), continuing until well after the onset of the HALAF phase (c.5000 BC). The first distinctive Samarra-culture assemblage was discovered by Herzfeld in 1912–14, during his excavation of the prehistoric cemeteries at the site. However, it was not until the excavation of the settlement and cemetery at TELL ES-SAWWAN (about 10 km south of Samarra itself) in the 1960s that the Samarra culture was identified as an important phase in the Neolithic of the Ancient Near East, particularly in the area of the Tigris valley. Its principal distinguishing features are pottery vessels decorated with skilfully painted geometrical and figurative motifs, female figurines made of terracotta and alabaster (similar to those of the UBAID period), and exquisitely carved marble vessels. Typical Samarraculture settlements and assemblages have been excavated at Tell Songor (Matsumoto 1987), while imported Samarra pottery has been found at the Ubaid site of Tell Abada in the Hamrin Basin. The ceramics of the late Samarra period at

(‘Choga Mami transitional pottery’) appear to have developed their own regional characteristics.

2 Islamic period. Samarra is also the key site for the Abbasid period (AD 750–1258), having been founded in AD 836 by the Caliph al-Muðtasim as a capital for himself and his Turkish military commanders and forces. It remained the capital until the Caliph Muðtamid was forced to move back to Baghdad in 892, and even after this date it was still occupied. Because of its Shiða shrine, it eventually developed into a pilgrimage centre in the mid-10th

SAMARRA 505

century. The excavations of Viollet, Sarre and Herzfeld, in 1910–13, provided detailed knowledge of the ground-plan of the mosques and palaces, through large-scale clearance of the vast palace of alMuðtasim, the palace of Balkuwârra, the Great Mosque and the Mosque of Abu Dulaf. A corpus of Abbasid paintings found in al-Muðtasim’s palace have provided the basic repertoire on which our knowledge of the subject still largely depends. The problem of the origin of the Abbasid lustreware and other fine glazed wares was, for the first time, able to be studied via a large body of material as a result of the excavations at Samarra.

3. Aerial photography and surface survey at Samarra. The history of the excavation and survey of Samarra is an excellent example of the changing approach to sites since the beginning of the 20th century. The massive clearances achieved with large (and cheap) labour forces that marked the first investigations at Samarra are no longer possible or even desirable. The work undertaken by Alastair Northedge in the 1980s addressed the enormous scale of the site through survey, and underlined how much of it had not been addressed by earlier research. Northedge’s work demonstrated the particular value of AERIAL PHOTOGRAPHY with the exploitation of a sequence of aerial photographs taken between 1924 and 1961. The process is applicable elsewhere and is especially effective where the landscape is undergoing rapid change as is the case in many parts of the Middle East.

In contrast to the earlier excavations, which had concentrated on the narrow period of the residence there of the Abbasid Caliphs, the new work recognized that the site was occupied both before and after its 9th century expansion and also that it was far larger than previously thought, extending for over 40 km along the River Tigris. The new study also included detailed examination of surface ceramics and their distribution, recognizing a far more complex picture, especially as a result of advances in ceramic analysis in recent years. An important new discovery is evidence of a glass production site in the southern part of Samarra. The industrial production of Samarra has always been a mystery, and it is often stressed that Sarre and Herzfeld discovered no pottery kilns at the site, leaving the source of lustreware and other glazed ceramics a matter for speculation.

H. Viollet: ‘Description du palais de al-Moutasim fils d’Haroun-al-Raschid à Samara et de quelques monuments arabes peu connus de la Mésopotamie’, Mémoires présenté par divers savants de l’Academie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres 12 (1909), 567–94; ––––: ‘Fouilles à Samara en Mésopotamie: un palais musulman du IXe siècle’,

506 SAMARRA

Mémoires présentés par divers savants à l’Academie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres 12 (1911), 685–717; E.E. Herzfeld: Die Malereien von Samarra (Berlin, 1927); ––––:

Die vorgeschichtlichen Töpfereien von Samarra (Berlin, 1930); ––––: Geschichte der Stadt Samarra (Berlin, 1948); A. Northedge: ‘Planning ‘Sâmarrâ: a report for 1983–4’, Iraq 47 (1985), 109–28; K. Matsumoto: ‘The Samarra period at Tell Songor A’, Préhistoire de la Mésopotamie, ed. J.L. Huot (Paris, 1987), 189–98; A. Northedge et al.: ‘Survey and excavations at Samarra, 1989’, Iraq 52 (1990), 121–47; M. Tampoe: Maritime trade between China and the West: an archaeological study of the ceramics from Siraf (Persian Gulf), 8th to 15th centuries AD (Oxford, 1989); A. Northedge: ‘Archaeology and new urban settlement in early Islamic Syria and Iraq’, The Byzantine and early Islamic Near East II land use and settlement patterns, ed. G.R.D. King and A. Cameron (Princeton, 1994), 231–65.

IS/GK

Samaria see ISRAELITES

sambaquís Immense shell mounds of partly natural and partly cultural origin found along the southern coast of Brazil. Although the first occupation of some sambaquís may have been as early as c.6500 BC, the main period of use was during the 1st millennium BC and later.

R.W. Hurt: Maritime adaptations in Brazil (Greeley, 1986).

KB

samples, sampling theory In statistical analysis, a sample is a set of objects drawn from a POPULATION; sampling theory consists of techniques, including and PARAMETER ESTIMATION, for making inferences about the population on the basis of DATA from the sample. For inferences to be valid, the sample must be representative of the population, i.e. it should be chosen according to a random sampling process. In the simplest case, ‘simple random sampling’, each object in the population has the same chance of selection; in more complex schemes the chances vary from one object to another, but can always be specified in advance. One aim of sampling theory is to derive the most information (often meaning the highest PRECISION) from the smallest possible sample, or the one requiring the least effort. The term is also used in a more general sense to mean a small part of a larger whole, e.g. a soil sample.

See QSAR ES-SEGHIR.

W.G. Cochran: Sampling techniques (New York, 1963); J.E. Doran and F.R. Hodson: Mathematics and computers in archaeology (Edinburgh, 1975), 42–3, 94–9; J.F. Cherry, C. Gamble and S. Shennan, eds: Sampling in contemporary

British archaeology (Oxford, 1978); C.R. Orton:

Mathematics in archaeology (Glasgow, 1980), 162–7; S. Shennan: Quantifying archaeology (Edinburgh, 1988), 298–330.

CO

sampling strategies Statisticians make a crucial distinction between a sampled population and a target population (see, for instance, Krumbein and Graybill 1965: 149; Doran and Hodson 1975: 95), and archaeologists’ sampling strategies are based on the assumption that there is a systematic relationship between samples of archaeological material (e.g. trenches excavated within a large site) and the entire set of archaeological material from a site, region or culture. Redman and Watson (1970) use systematic intensive surface collection of artefacts at two prehistoric mounds in southeastern Turkey (Çayönü and Girik-i-Haciyan) to explore the strengths and weaknesses of various sampling designs and analytical procedures. They argue that, providing such factors as weather, local topography, number of phases present and amount of human disturbance are taken into account, a multivariate model can be constructed of the relationship between surface and subsurface material at any particular site. At the INCA urban site of Huánuco Pampa, 275 km northeast of Lima, Morris (in Mueller 1975) uses the architectural plans (constituting an estimated 80% of the city’s original buildings) to divide the city into eight basic zones, five of which are then subdivided to produce a total of 21 ‘spatially separated strata’.

For a case-study see EL-HIBA.

W.C. Krumbein and F.A. Graybill: An introduction to statistical models in geology (New York, 1965); C.L. Redman and P.J. Watson: ‘Systematic intensive surface collection’, AA 35 (1970), 279–91; J.E. Doran and F.R. Hodson:

Mathematics and computers in archaeology. (Edinburgh, 1975); J.W. Mueller, ed.: Sampling in archaeology (Tucson, 1975); R.D. Drennan: Statistics for archaeologists: a commonsense approach (New York and London, 1996), 79–98 passim.

IS

San Agustín Region in southern Colombia, around the head waters of the Magdalena River, where the people occupying a series of agriculture villages of the Isnos phase (c.AD 100–1200) erected elaborate stone statues depicting supernatural figures, animals and humans as part of their mortuary practices. The statues were buried in stone cists or left in the barrow chambers or passages, probably serving protective functions for the dead.

L. Herrera, ed.: San Agustín 2000 años 1790–1990:

Seminario: La arqueología del Macizo y el suroccidente Colombianos (Bogotá, 1991); K.O. Bruhns: ‘Monumental sculpture as evidence for hierarchical societies’, Wealth and hierarchy in the Intermediate area, ed. F. Lange (Washington, D.C., 1992), 331–56.

KB

Sanchi Buddhist site located near Bhopal in central India, dating from the 3rd century BC to the 11th century AD. The site contains a number of significant Buddhist monuments enclosed within a massive stone wall which postdates most of the construction at the site. Structures within the walled area include STUPAS, shrines, temples and monasteries.

J. Marshall: Excavations at Sanchi, Archaeological Survey Reports II (Delhi, 1914); ––––: A guide to Sanchi (Delhi, 1936); M.K. Dhavalikar: Sanchi: a cultural study (Pune, 1965); K.K. Murthy: Material culture of Sanchi (Delhi, 1983).

CS

Sanghao Cave Palaeolithic cave site in northwest Pakistan, which was excavated by Ahmad H. Dani in the 1960s. Twelve stratified levels were identified in 3 m of deposit; levels 12–5 date to the Palaeolithic period, disturbed levels 4–3 contain microliths, and Buddhist remains were found in the upper two levels. The lithic artefacts were made of quartz, while artefacts from the Palaeolithic levels included a small handaxe, scrapers, awls, and burins, as well as prepared cores and flakes produced by the LEVALLOIS technique. No absolute dates are available for Sanghao Cave.

A.H. Dani: ‘Sanghao excavation: the first season, 1963’, AP 1 (1965), 1–50; B. Allchin: ‘Blade and burin industries of West Pakistan and Western India’, South Asian archaeology, ed. N. Hammond (Cambridge, 1973), 39–50.

CS

Sangoan (Sangoan-Lupemban) ‘Industry’ in Central Africa, which was once thought to be part of a typological succession of post-ACHEULEAN macrolithic ‘forest industries’ but is now much more cautiously defined. First found by E.J. Wayland on the hills above Sango Bay on the west side of Lake Victoria, most finds of the Sangoan and related industries have been from surface collections along river terraces. Only a few in situ living floors are known, including KALAMBO FALLS (Zambia) and the Mwaganda Elephant Kill site (Malawi). Desmond Clark (1959) linked the first Sangoan finds to an adaptation to forest environment with picks being used for digging tubers and

SANGOAN 507

animal traps, chopping tools for bringing down trees, and push-planes for the working of wood. Indeed, the distribution of these SangoanLupemban fossiles directeurs may still be shown to follow the modern Central and West-Central African forest and savanna-forest ecozones.

However, some of the initial suppositions about the Sangoan were shown to have been false as research progressed. Firstly, the Sangoan was thought to be dominated by heavy duty tools (e.g. crude picks, push planes and cleavers), while the Lupemban was thought to be a later variant distinguished by the presence of fine lanceolates. However, the excavated living floors of Kalambo Falls showed heavy duty tools to be in the minority (>30%) with flake scrapers and other ‘light duty tools’ comprising at least 60% of the lithic assemblage in most contexts (Clark 1970). Similar heavy-duty–light-duty ratios have since also been demonstrated at ASOKROCHONA (Ghana) and Muguruk (Kenya).

Additionally, the research of Daniel Cahen has cast doubt on the security and universality of the initial temporal ordering of Acheulean–Sangoan– Lupemban–Tshitolean. From a re-excavation of the important GOMBE POINT (Zaire) stratigraphic succession, Cahen (1976) was able to show that lithic conjoins cross-cut the sequence, with an additional tendency for artefacts of greater volume to be lower in the sequence than those of lesser volume. He subsequently suggested that millennia of river terrace re-working has hopelessly skewed most known sequences from Central African river basins, and that most so-called industries were only ‘pseudo-industries’. Cahen thus suggested the abandonment of most of the post-Acheulean stone age sequence for Central Africa, with a re-start from scratch. In the meantime the broad terms Acheulean complex and post-Acheulean complex were suggested (Cahen 1978).

However, other researchers such as Sally McBrearty have called for the retention of the name ‘Sangoan’ at a TECHNOCOMPLEX level, since it still describes a broad macrolithic core tool adaptation which can be shown to have post-dated the Acheulean and pre-dated ‘MOUSTERIAN’ industries in central Africa. In Western Kenya at Muguruk, McBrearty has had the good fortune to find relatively rich deposits with their stratigraphic integrity intact. These deposits showed a succession from a local Ojolla industry (of Sangoan-Lupemban technocomplex) to a Pundo Makwar (of LEVALLOIS Mousterian technocomplex). The Sangoan can also be shown to underlie Levallois technology at Asokrochona (Ghana).

508 SANGOAN

The age range of the Sangoan-Lupemban technocomplex remains uncertain. Dates include a c.200,000 BP ESR (electron spin resonance) determination on the Kabwe (Broken Hill, Zambia) archaic Homo sapiens remains (associated with supposed Sangoan light-duty components), and a date of greater than 130,000 BP at Lake Eyasi (Tanzania) where archaic Homo sapiens remains are also associated with a ‘Sangoan’ industry. Other dates are either minimum (40,000+ BP) ones, from several sites including Kalambo Falls, or seemingly aberrant dates for ‘Lupemban’ localities in the Lunda regions (Angola) which are as recent as c.15,000 BP.

J.D. Clark: The prehistory of Southern Africa (London, 1959); ––––: The prehistory of Africa (London, 1970); D. Cahen: ‘Nouvelles fouilles à la Pointe de la Gombe (exPointe de Kalina), Kinshasa, Zaire’, L’Anthropologie 80 (1976), 573–602; ––––: ‘Vers une revision de la nomenclature des industries préhistoriques de l’Afrique Centrale’, L’Anthropologie 82 (1978), 5–36; P. AllsworthJones: ‘The earliest human settlement in West Africa and the Sahara’, WAJA 17 (1987), 87–129; S. McBrearty: ‘The Sangoan-Lupemban and the Middle Stone Age sequence at the Muguruk site, western Kenya,’ WA 19 (1988), 388–420; P. Allsworth-Jones: ‘The archaeology of archaic and early modern Homo sapiens: an African perspective’, CAJ 3 (1993), 21–39.

KM

San-hsing-tui (Sanxingdui) Chinese Neolithic site with cultural levels from LUNG-SHAN through to the SHANG and CHOU periods (c.2000–1000 BC) including the remains of a city wall. The site is situated 8 km from Kuang-han hsien (Guang-han) in the province of Ssu-ch’uan, China. In 1986, the excavations of two unusual pit burials containing a vast hoard of bronze artefacts, jade objects, elephant tusks and gold-foil ornaments, caused a considerable stir throughout China and the archaeological world. The bronze-using culture at San-hsing tui was of a kind that had not hitherto been found in China, and had no apparent affinities elsewhere: it appeared to be culturally isolated from the surrounding Neolithic environment.

Among the more curious artefacts are such items as a standing bronze statue (260 cm) of pre-Han date, several bronze masks (the largest having a width of 138.5 cm) with cylindrical pupils protruding from the eyes, a series of bronze heads with ‘inverted’ eyes and square chins – the latter feature reminiscent of wood sculpture – and various other bronze artefacts, including several vessels obviously deriving from other areas of China, some of the latter datable as early as Western Chou.

Although the cultural remains have been dated to the Late Shang period (c.1400–1122 BC) by the local excavators, there are significant parallels of ornamentation with that of the 6th-and 5th-century art of CH’U. The full significance and date of the find have yet to be acceptably determined, including any association it may have had with the

cultures of Western China.

N. Barnard: ‘Some preliminary thoughts on the significance of the Kuang-han pit-burial bronzes and other artifacts’, Beiträge zur Allgemeinen und Vergleichenden Archäologie 9–10, (1990), 249–80.

NB

San Jacinto see PUERTO HORMIGA, MONSÚ AND SAN JACINTO

San José Mogote Small Formative-period village in an agriculturally highly productive portion of the valley of Oaxaca, Mexico, which came to prominence between 1100 and 800 BC, reaching its peak around 700–500 BC. The traditional idea of the primacy of the OLMEC culture in the genesis of Mesoamerican civilization has been challenged by the presence, at San José Mogote, of early public architecture and evidence of the use of status symbols. Investigators recognized residential neighbourhoods at the village, differentiated by distributions of motifs on pottery in burials and areas of specialized craft production. San José Mogote functioned as the major civic centre of the Etla (northern) arm of the Valley of Oaxaca until the founding of MONTE ALBAN.

Marcus and Flannery (1994) have used the ‘direct historical approach’ and COGNITIVE

ARCHAEOLOGY to examine ZAPOTEC ritual and

religion, demonstrating that many elements of ritual described in 16th century accounts have been preserved in the archaeological record at San José Mogote. The excavation of Structure 35, for instance, has revealed material evidence of the activities of the bigaña (priests), including bloodletting with prismatic obsidian blades and the use of obsidian daggers to sacrifice not only quails and turkeys but also human slaves and prisoners of war, all of which are described in 16th century texts. However, the archaeological work also goes beyond the documentary records to show that the Zapotec turned secular ground into sacred ground by including valuable offerings in the temple foundations (as in the case of ‘Features 94–96’). Marcus and Flannery (1994: 71–2) therefore make the point that cognitive archaeology at such sites as San José Mogote lies at the interface between archaeology

and history: ‘First ethnohistory tells us what a temple should look like and accurately predicts that we should discover obsidian blades, sacrificial knives, incense burners and quail. Archaeology then reveals unpredicted offerings beneath the temples, but ethnohistory gives us some clues for interpreting them. In the case of Feature 96 at San José Mogote, it suggests that we are seeing metamorphosis, a major career transition of deceased royalty’.

K.V. Flannery, ed.: The early Mesoamerican village (New York, 1976); J. Marcus and K.V. Flannery: ‘Ancient Zapotec ritual and religion: an application of the direct historical approach’, The ancient mind: elements of cognitive archaeology, ed. C. Renfrew and E. Zubrow (Cambridge, 1994), 55–74.

PRI

San Lorenzo Tenochtitlán Complex of early

OLMEC (Middle Formative) sites – San Lorenzo, Tenochtitlán (Río Chiquito) and Potrero Nuevo – in the Gulf coast region of Veracruz, Mexico. Best known is San Lorenzo proper, dating after 1500 BC, which was built by raising and enlarging a natural promontory, possibly in effigy form. Its primarily public/ceremonial architecture includes more than 20 earthen mounds, a series of ponds or lagoons with drainage troughs, and at least 75 sculptured monuments. The site is usually seen as a ceremonial centre because of the comparative lack of evidence for domestic occupation.

M.D. Coe and R.A. Diehl: In the land of the Olmec, I: The archaeology of San Lorenzo Tenochtitlán (Austin, 1980).

PRI

San Pedro de Atacama Major oasis in the Atacama desert of Chile, and the scene of human activity from the earliest PALEOINDIAN hunting groups through to the development of sedentary farming/herding communities increasingly under the influence of PUCARA and TIAHUANACO and finally falling to the INCAS. The site is especially important because the aridity of the desert has ensured excellent preservation of organic materials.

A.M. Barón Parra: ‘Tulor: posibilidades y limitaciones de un ecosistema’, Revista Chungara 16–17 (1986), 149–58; M. Rivera: ‘The prehistory of Northern Chile: a summary’, JWP 5/1 (1991), 1–47.

KB

Santorini |

see THERA |

|

San Vincenzo al Volturno |

Major Benedictine |

|

monastery |

in the Appennines |

of Central Italy, |

SAN VINCENZO AL VOLTURNO 509

which flourished between the 8th and 12th centuries AD. Excavations in 1980–94 brought to light many elements of an early medieval monastery, preserved thanks to an Arab sack of October 10, 881. The history of the monastery is well-established as a result of a 12th-century account, the Chronicon Vulturnense. The deserted site first came to notice with the discovery of a complete painted crypt in 1832, including one panel on which Abbot Epyphanius (AD 824–42) is depicted. Excavations commenced in 1980 to examine the layout of an early medieval monastery, following the publication of Walter Horn and Ernest Born’s The Plan of St Gall (see ST GALL ABBEY), and a sequence of monastic plans has now been identified (Hodges 1993–5).

The builders of the first monastery effectively reused a Late Roman villa, covering about half a hectare, which was possibly the seat of the bishop of Samnium. The 5th-century funerary church became the first early medieval abbey-church. Later in the 8th century a painted altar was made in its apse, and a fine ambulatory had by then been added, in order to provide visitors with a view of the altar.

In the early 9th century Abbot Joshua created a monastic city – the second lay-out – modelled upon Carolingian prototypes. A triple-apsed abbeychurch, 63 m long and 28 m wide, was consecrated in 808. The old monastery was converted into quarters for distinguished guests. In between lay the cloisters with provision for over 300 monks. South of the abbey lay a collective workshop. Many other buildings have also been provisionally identified in a complex that now covered 6 ha. Most parts of the monastery were richly painted, while re-used Roman spolia were incorporated in most buildings. A rich material culture, including a prolific use of glass, distinguishes this phase. Abbot Joshua’s plan was enlarged by Abbot Epyphanius when the abbey-church was aggrandized with an eastwork, and the distinguished guests’ palace was enlarged with a new western apsidal end. In 848 an earthquake damaged several buildings.

Thereafter, until the comprehensive Arab sack in 881, the monastery fell slowly into decline. With the development of its territory in the later 10th century, San Vincenzo emulated its neighbour, Monte Cassino, by building a new romanesque monastery

– a third lay-out – involving the demolition of the earlier ruins. Built between c.AD 1000 and 1060, this typical, compact settlement was subjected to attacks by local families. As a result the Romanesque monastery was dismantled and transposed to a new defensible site some 400 metres away. Here the

510 SAN VINCENZO AL VOLTURNO

Chronicon |

Vulturnense |

was written soon |

after |

the move, |

recalling the |

colourful history |

of the |

earlier site. A monastery still exists at the site in modern times.

C. Wickham: I1 problema dell’ Incastellamento nell’ Italia Centrale: L’esempio di San Vincenzo al Volturno (Florence, 1985); J. Mitchell: ‘Literacy displayed: the use of inscriptions at the monastery of San Vincenzo al Volturno in the early ninth century’, The uses of literacy in early Medieval Europe, ed. R. McKitterick (Cambridge, 1990), 186–225; R. Hodges, ed.: San Vincenzo al Volturno, 2 vols (London, 1993–5).

RH

Sanxingdui see SAN-HSING-TUI

Sapalli (Sapalli-tepe) Bronze Age fortified settlement located on the Amu-Darya plain, 70 km west of the town of Termez in southern Uzbekistan, Central Asia. Excavated by Askarov (1973), the site (c.4 ha) includes a central area fortified by a system of walls, and a ‘lower area’ where three construction levels were recognized. The earlier two phases belong to the ‘Sapalli culture’ of about 2200–1800 BC, and the later one to the ‘Jarkutan culture’ of about 2000 BC. The settled area in the first level of the lower area contained eight distinct large residential units, interpreted as separate ‘patriarchal households’. Each of these had several domestic hearths and evidence for pottery production. The number of residences nearly doubled in the second level, but the structures were destroyed by fire at the end of the period. The later settlement, corresponding to the third level, was much smaller. A total of 138 graves had been studied, mostly in the central fortified area of the site (which was possibly occupied by the social elite): 29 burials contained metal and stone objects; 23 female graves included toilet articles; graves of infants and children had a poorer assortment of goods.

A. Askarov: Sapallitepa (Tashkent, 1973); ––––:

‘Southern Uzbekistan in the second millennium BC’, The Bronze age civilization of Central Asia, ed. P. Kohl (Armonk, 1981); P. Kohl: Central Asia: Palaeolithic beginnings to the Iron Age (Paris, 1984), 154–8.

PD

Saqqara Necropolis associated with the Egyptian city of MEMPHIS, southwest of Cairo, with funerary and religious buildings dating from c.3000 BC to AD 950. It included the tombs of elite officials of the Early Dynastic period (c.3000–2649 BC); the Step Pyramid complex of King Djoser (c.2620 BC; the pyramids of the 5th-

and 6th-dynasty rulers Unas, Userkaf, Teti, Pepi I and II, Merenra, Shepseskaf and Djedkara Isesi; the tombs of New Kingdom officials such as the 18th-dynasty general Horemheb (c.1310 BC); the Serapeum (c.1250–BC–AD 400), where the sacred Apis bulls were buried from at least the reign of Amenhotep III until the Ptolemaic period (c.1400–30 BC); the Sacred Animal Necropolis, and many other tombs, temples and shrines. Northern Saqqara also incorporates the ruins of the monastery of Appa Jeremias, founded around the end of the 5th century AD and abandoned by the late 9th century.

J.-P. Lauer: Saqqara: the royal cemetery of Memphis

(London, 1976); G.T. Martin: The sacred animal necropolis at north Saqqara (London, 1981); ––––: The hidden tombs of Memphis (London, 1991); W.B. Emery: Great Tombs of the first dynasty 3 vols, (Cairo and London, 1949, 58); J. van Dijk, The New Kingdom necropolis of Memphis: historical and iconographical studies (Groningen, 1993).

IS

Sarab, Tepe see LURISTAN

Saraçhane Site of the lost early Byzantine church of St. Polyeuktos, built by Anicia Juliana in AD 524–7 and excavated in 1964–9. This was one of the major churches of Constantinople in the early Byzantine period. The excavations (like those at the Cripta Balbi, Rome; Manacorda and Zanini 1989) provided the first sequence of archaeological deposits containing objects extending from the 6th century to the later Middle Ages. These include domestic pottery, glassware, and metalwork, making Saraçhane ‘a type site’ for early to middle Byzantine archaeology.

R.M. Harrison: Excavations at Saraçhane (Istanbul and Princeton, 1986); D. Manacorda and E. Zanini: ‘The first millennium AD in Rome: from the Porticus Minucia to the Via delle Botteghe Oscure’, The birth of Europe, ed. K. Randsborg (Rome, 1989), 25–32.

RH

Sarazm Eneolithic-Bronze Age site consisting of ten small mounds, situated in the Zerafshan Valley near the medieval town of Penjikent in Tadjikistan. The site has been excavated since 1977 by Isakov with the help of French archaeologists. Several radiocarbon measurements suggest a calender date of around 3250–2750 BC. A small cemetery belonging to the initial stage shows some elements of the burial rite typical of steppe groups to the north. The pottery corpus reveals elements of the GEOKSYUR style, in association with styles related to SistanBaluchistan and Northern Iran (Hissar III B). The typology of the locally produced copper tools, based

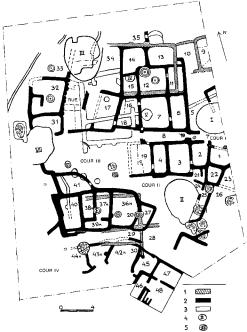

Figure 45 Sarazm Eneolithic–Bronze Age settlement at Sarazm, Tadjikistan: (1) walls of Sarazm III, (2) walls of Sarazm II, (3) walls of Sarazm I, (4) ditches, (5) hearths. Source: A. Isakov: ‘Excavations of the Bronze Age settlement of Sarazm’, The Bronze Age civilization of Central Asia, ed. P. Kohl (Armonk, 1981), fig. 3.

on local metallurgy, also reveals North Iranian affinities. The Sarazm tradition is usually interpreted as resulting from an interaction between Geoksyur-related agricultural groups (migrating from the ‘northern foothills’ of the Kopet Dag) and local social units.

A. Isakov: ‘Excavations of the Bronze Age settlement of Sarazm’, The Bronze age civilization of Central Asia, ed. P. Kohl (Armonk, 1981), 273–86.

PD

Sarnate Group of Neolithic settlements, dated to between about 3500 and 2900 BC in calendar years and situated in the marginal zone of a peat-bog in the coastal area of western Latvia (south of the town of Ventspils). The sites were discovered and excavated by L. Vankina in the 1960s. There were over 40 dwellings built on piles over sandy foundations, and varying in size from 3 to 15 sq. m. The faunal remains, although limited in quantity, included elk, beaver, wild boar and seal. One of the

SASANIAN 511

dwellings was completely filled with fish bones. Large amounts of water chestnut (Trapa natans) were found in all of the excavated dwellings. Several large fragments of boats (made of single treetrunks), as well as numerous oars, were found. Amber ornaments – including disks, buttons, rings and pendants – were discovered within most of the structures. Several clay figurines and wooden anthropomorphic sculptures have also been recovered.

L.V. Vankina: Torfjanikovaja stojanka Sarnate [Sarnate peat site] (Riga, 1970).

PD

sarsen Natural boulder of silicified sandstone, probably formed during the Tertiary age, and shaped and deposited by glacial action. Large groups of sarsens appear at surface level in areas of the Marlborough Downs in Wiltshire, England, where they formed ideal material for the construction of monuments such as AVEBURY and the trilithons of STONEHENGE. Most of the natural sarsen fields have now been broken up for use in more recent constructions, but a preserved group can be seen at Fyfield Down, near Avebury in Wiltshire.

RJA

Sasanian Iranian dynasty, founded by Sasan in AD 208, which dominated most of the ancient Near East from the fall of the PARTHIAN empire in 224 until the assassination of Yezdegerd III in 651, followed by the gradual Islamicization of the local population. The Sasanian rulers considered themselves to be the true heirs of the Achaemenid empire (see PERSIA), regarding their Parthian predecessors as westernized usurpers of the throne. Typical Sasanian cities incorporated palaces and fire temples retaining some of the architectural styles that had characterized Parthian public buildings. There are surviving remains of typical Sasanian palaces at such sites as Firuzabad, Bishapur and Qasr-i Shirin, Ctesiphon and KISH. The sides of a deep gorge near the city of Bishapur in western Iran are decorated with six distinctive Sasanian rockcarved reliefs depicting Shapur I’s victory over the Romans in AD 266.

R. Ghirshman: Bichâpour, 2 vols (Paris, 1956–72); ––––:

Parthes et Sassanides (Paris, 1962); P.O. Harper: The royal hunter (London, 1978); G. Herrmann: The Iranian revival (Oxford, 1977); B.J. Overlaet et al., eds.: Splendeur des Sassanides exh. cat. (Brussels, 1993).

IS

512 SATSUMON

Satsumon Culture found in Hokkaido, Japan between the 4th and 14th centuries AD, partly associated with the Emishi ethnic group, contemporary with the Kofun and Early Historic periods further south in Japan (see JAPAN 4–5). Characterized by the use of iron, incised pottery similar to the Haji ware of Kofun period and the cultivation of cereals such as millet, it was partly contemporary with the OKHOTSK culture.

E. Yokoyama: Satsumon bunka (Tokyo, 1990); Y. Fukasawa: ‘Emishi and the Ainu: from an archaeological point of view’, Paper presented at Japanese archaeology in protohistoric and early historic period: Yamato and its relations to surrounding populations, International symposium at the University of Bonn, 1992.

SK

Sauveterrian Term applied to an ill-defined group of Mesolithic assemblages, characterized principally by the presence of small triangular points and narrow blades. First identified at Sauve- terre-la Lemance, southwest France, the assemblages date from about 7000 BC onwards, being produced for perhaps a millennium. Kozłowski interprets the Sauveterrian as an assemblage type, originally including a specific tool-kit, that evolved in southern France and was then adopted to a greater or lesser extent through much of west and central Europe (including Britain). Sauveterrian assemblages are generally thought to post-date assemblages defined as MAGLEMOSIAN, or to be contemporary with the later Maglemosian, and to predate assemblages defined as TARDENOISIAN; however, the relationship with the Tardenoisian has been the subject of much debate since the 1950s, as summarized by Peter Rowley-Conwy (1986). It seems clear that in most regions the Sauveterrian does not represent a ‘culture’; whether its spread represents some change in implement use and economy, or whether it is simply a stylistic phenomenon, is as yet undecided.

S.K. Kozłowski, ed.: The Mesolithic in Europe (1973); J.K. Kozłowski: ‘Les industries à pointes à cran en Europe Centre-Est’, Ixe Congrès UISPP, Nice, Coll. XV (Paris, 1976), 121–7; P. Rowley-Conwy: ‘Between cavepainters and crop planters: aspects of the temperate European Mesolithic’, Hunters in transition, ed. J. Zvelebil (Cambridge 1986), 17–29.

RJA

Sawwan, Tell es- The classic site of the SAMARRA culture (c.5600–5000 BC), located on the left bank of the Tigris north of Baghdad, in central Iraq. It incorporates several strata of settlement remains dating back to the HASSUNA phase

(c.5800–5500 BC), providing the first clear evidence that the painted pottery originally discovered at the site of Samarra was not simply a specialized form of Hassuna ceramics but a cultural sequence in its own right. The earliest Samarra settlement at Sawwan consisted of large rectangular multi-room buildings, each constructed with long mud bricks and provided with external buttresses, the whole settlement being surrounded by a 3 m deep ditch. The individual buildings each covered about 150 sq. m and were initially interpreted as granaries (Roux 1992: 54) although all are probably domestic structures. In later phases the houses were much smaller (only about 70 sq. m) and the settlement plan as a whole was considerably looser and defended by an enclosure wall as well as the ditch. The people of Tell es-Sawwan, as at CHOGA MAMI further to the east, evidently relied on a subsistence base including the cultivation of wheat and barley as well as cattle herding and hunting; their use of irrigation agriculture and the construction of impressive mud-brick buildings all suggest that the Samarra culture represented a distinct prelude to the process of urbanization in Mesopotamia.

Preliminary reports by B. Abu es-Soof et al. in Sumer 21–26 (1965–70); H. Helbaek: ‘Early Hassunan vegetables from Tell es-Sawwan, near Samarra’, Sumer 20 (1964), 45–8; J. Oates: ‘The baked clay figurines from Tell esSawwan’, Iraq 28 (1966), 146–53; G. Roux: Ancient Iraq, 3rd edn: (Harmondsworth, 1992), 53–5; C. Breniquet: ‘Tell es-Sawwan: réalités et problèmes’, Iraq 53 (1991), 75–90.

IS

Sayala see A GROUP

Sayil One of several large Mesoamerican sites in the PUUC region of the northwestern Yucatán peninsula, Sayil recently the focus of mapping and excavations in the 1980s, designed to understand how and why this region flourished during the tumultuous Terminal Classic period (c.AD 800–1000), when sites further to the south were subject to the LOWLAND MAYA ‘collapse’. The city was occupied by approximately 10,000 people, while another 7000 lived around the urban core. House platforms had garden plots in the vicinity and CHULTUNES served for storing water.

J.A. Sabloff and G. Tourtellot: The ancient Maya city of Sayil: the mapping of a Puuc region center (New Orleans, 1991).

PRI

scanning electron microscope (SEM)

Type of microscope in which an extremely fine beam of electrons (5–100 kV) is used to scan an area of a goldor carbon-coated specimen in a series of parallel lines. Secondary electrons emitted from the surface of the specimen along the lines can be used to reproduce an image of the specimen via a cathode ray tube. These high resolution three-dimensional images can then be magnified up to 100,000 times, providing considerably more depth of focus than conventional microscopes. The SEM can thus reveal details of morphologies and textures too small to be seen in thin sections, allowing it to be used for such archaeological purposes as the study of ancient food remains (Dronzek et al. 1972) and the provenancing of stone artefacts (Middleton and Bradley 1989). The ‘electron microprobe’ is a combination of a scanning electron microscope and multiple wavelength dispersive spectrometers; it can be used to perform fully quantitative elemental analyses of specimens. For further discussion see

ELECTRON PROBE MICROANALYSIS (EPMA) and

X-RAY FLUORESCENCE SPECTROMETERY (XRF).

B.L. Dronzek et al.: ‘Scanning electron microscopy of starch from sprouted wheat’, Cereal Chemistry 49/2 (1972), 232–9. A. Middleton and S.M. Bradley: ‘Provenancing of Egyptian limestone sculpture’, JAS 16 (1989), 475–88.

IS

scapulimancy Chinese method of divination, using the reading of features such as colourations and cracks in animal shoulder blades to predict future happenings or explore the advisability of carrying out some planned activity. In the related method of PLASTROMANCY, turtle plastrons were employed for the same purpose. A distinction should be made between apyro-scapulimancy, where the natural condition of the bone (after scraping away the flesh) is read, and pyro- scapulimancy, where the bone is heated in order to create ‘omen cracks’. Pyro-scapulimancy was common in Neolithic China, while in the Late Shang period (c.1400–1123 BC) incised writings were added both before and after the heat-induced omen cracks were read. Due to the latter practice, a large corpus of archaeological documents, the ORACLE BONES, has accumulated since the beginning of the 20th century, providing invaluable insights into many aspects of Shang culture (see

CHINA 3).

D.N. Keightley: Sources of Shang history: the oracle-bone inscriptions of Bronze Age China (Berkeley, 1978).

NB

SCYTHIANS 513

scarab Type of seal found in Egypt, Nubia and Syria-Palestine from the 6th dynasty until the Ptolemaic period (c.2040–30 BC). It derives its name from the fact that it was carved or moulded in the form of the sacred scarab beetle Khepri. The flat base was usually decorated with designs or inscriptions, sometimes including a royal name.

P.E. Newberry: Ancient Egyptian scarabs: an introduction to Egyptian seals and signet rings (London, 1905; repr. Chicago, 1979); M. Malaise: Les scarabées de coeur dans l’Egypte ancienne (Brussels, 1978); C. Andrews: Amulets of ancient Egypt (London, 1994), 50–9.

IS

scattergram, scatterplot Graphical representation of archaeological DATA in which two variables are represented along two axes, and objects are plotted as points whose locations are fixed by the values taken by the variables on each object. Objects that are ‘similar’ to each other appear close to each other on the plot and ‘dissimilar’ objects are located away from each other. It is often used to give a visual impression of the out-

come of a PRINCIPAL COMPONENTS ANALYSIS or a

CORRESPONDENCE ANALYSIS, in which case the

variables plotted are combinations of the original variables.

CO

Scythians Predominantly nomadic groups of the steppe regions of Ukraine and southern Russia, mid-to late 1st millennium BC. The first excavations of Scythian antiquities in Southern Russia and Ukraine date back to 1763, when General A.P. Melgunov opened a series of magnificent barrows near the town of Elizavetgrad (Kirovograd). In 1830, P. Dubrux discovered and excavated the stone burial chamber at Kul-Oba barrow, near the town of Kerch in eastern Crimea. Intensive excavations of Scythian barrows at the turn of the century were carried out by N.I. Veselovsky, while the settlements and hill-forts (gorodisˇcˇe) in the forest-steppe zone were studied by A.A. Spitsyn and V.A. Gorodtsov.

In the Soviet era, large-scale excavations of both barrows and settlements were conducted by A.I. Terenozhkin, B.M. Mozolevsky, I.B. Brashinsky and others. The problems related to the origin, ethnicity and social pattern of Scythian groups were discussed by scholars such as M.I. Rostovtseff, V.I. Ravdonikas, M.I. Artamonov, P.D. Liberov, and A.M. Khazanov. Three main groups of Scythian sites are distinguished in the Pontic steppes: (1) Central steppe; (2) Lower Don; (3) Crimean steppe.

514 SCYTHIANS

Scythian burials in the steppe areas mainly take the form of barrows (kurgans), which start to emerge at the turn of the 7th/6th centuries BC in a region stretching from the Danube to the Don. From the end of the 5th century BC, the barrows tend to cluster in the Low Dniepr, the Low Southern Bug and in the Dniestr-Danube interfluve. The number of ‘rich’ barrows increases from this period, though most of the so-called ‘royal tombs’ belong to the 4th century BC. In terms of physical size, the tallest barrows are: Alexandropol (21 m); Chertomlyk (19 m); Oguz (20 m); Bol’shaya Tsymbalka (15 m); Kozel (14 m). There is also a range of medium-sized monuments such as Melitopol (6 m); Tolstaya Mogila (8.6 m); and Gaimanova Mogila (8 m). By contrast, the barrows of common tribesmen are usually less than 2 m in height and less than 100 m in diameter; they form cemeteries consisting of 10–15 (occasionally up to 100) barrows.

The barrows usually cover either rectangular or oval-shaped graves; timber burial chambers and catacombs were also sometimes constructed. The latter become particularly complex in the case of the royal tombs. Inhumation was the predominant burial rite: the dead were usually laid on their backs, and more rarely in a contracted posture on the right or left side. The head was directed either to the west or northwest. About 80% of the burials are single graves, and multiple burials started to occur only after the 4th–3rd centuries BC. The body was often placed on a mat of reed, grass or bark, or more rarely on skin or fur. Coffins or sarcophagi were employed only in the richest tombs (Chertomlyk, Melitopol, Tolstaya Mogila, Oguz).

The burial inventory of common tribesmen usually included a quiver and arrowheads and, rarely, one or two spears; still more rarely, a sword, a dagger or armour were added or (in very exceptional cases) elements of horse gear. Female graves of the commoner sort tend to contain clay or plumb spindle-whorls and various ornaments, although perhaps 25–27% of common female graves contain weapons (arrows, spears, swords or daggers; more rarely a belt with gold plaques). Both male and female graves might contain a ‘meal’, as evidenced by the bones of sheep, cattle or horse. Cemeteries close to Greek colonies often contained Greek-made drinking vessels.

The rich burials reveal considerable social differentiation in Scythian society. From the 5th century BC, the richest tombs were often augmented by burials of horses and human attendants. In some cases (e.g. Strashnaya Mogila, mound 1), horse and human burials accompanied tombs that in other

respects are not particularly rich. Horse burials are most often found associated with male tombs, but in some cases accompany rich female graves (Khomina Mogila, Gaimanova Mogila, Solokha, Alexandropol). In some examples (Chertomlyk), the graves of servants contained a rich series of grave goods (including gold and silver implements). At Chmyreva Mogila and Gaimanova Mogila, women apparently killed at the time of the funeral were buried in separate chambers that contained items comparable with those buried with the ‘king’. All royal tombs contain numerous decorative gold ‘plates’ (up to 2000) which were sewn onto clothing. Both male and female tombs contained bracelets and gold pendants. The number of ritual vessels varied from 1–2 to 10; these were mostly Greekmade amphorae, kitchen vessels or bronze cauldrons containing the remains of a ritual meal (horse, goat or cattle). The tombs of rich warriors contained trimmed quivers with arrows, one or several swords, and hatchets. The graves of noble Scythian women usually contained mirrors, glass and gold beads, various ornaments of precious metals, bronze and ivory – predominantly of Greek workmanship.

Permanent settlements started to appear in the steppe area in the late 5th century BC. The largest settlement, Kamenskoe, on the river Dniepr, opposite Nikopol, reached the size of 12,000 sq. km. The settlement boasted a large citadel, and was protected by earthern walls and ditches. Bronze and iron tools and blacksmith’s implements were found around many of the houses. The settlement of Elizavatovskaya was situated on one of the islands in the Don delta. The site emerged at the turn of the 6th/5th centuries BC as an important centre of maritime trade and crafts, and was encircled in the 4th century BC by a system of defensive walls and ditches.

The economy of most Scythian groups is thought to have been based on nomadic stock-breeding. The faunal remains reveal a predominance of cattle (which were also used as draught animals) and horse. At least in the Lower Dniepr and the Lower Don, there was also a fallow system of agriculture based on the cultivation of rye, Italian millet and emmer.

In the forest-steppe zone, a system of fortified settlements (gorodisˇcˇe) emerged from the 7th century BC. Eight local groups are distinguished: the Middle Dniepr (Right Bank); the Southern Bug; West Podolian; Vorksla; Seima; North Donetsian; Sula; and the Middle Don. These groups are often identified with the ‘Scythian cultivators’, ‘who grow corn not for their own use, but