A Dictionary of Archaeology

.pdftype found in a grave is used as the score of the grave). This creates a ranking of graves, from those with many different types through those with few types to those with one or none. The interpretation of the ranking is then up to the archaeologist. It is often necessary to analyse male and female graves separately (see GENDER ARCHAEOLOGY). The main drawback of social status analysis is that large samples (about 100+ graves) are needed for the technique to work well.

F.R. Hodson: ‘Quantifying Hallstatt’, AA 42 (1977), 394–411; J. Brenan: ‘Assessing social status in the AngloSaxon cemetery at Sleaford’, Institute of Archaeology Bulletin 21/22 (1985), 125–31.

CO

sodium profile dating Scientific dating tech-

nique similar to NITROGEN PROFILE DATING,

which has been used on OBSIDIAN but has not yet been fully developed (see also OBSIDIAN

HYDRATION DATING).

G. Coote and P. Nistor: ‘Depth profiles of sodium in obsidian by the resonant nuclear reaction method: a potential dating technique’, Archaeometry: an Australian perspective, ed. W. Ambrose and P. Duerden (Canberra, 1982), 243–50.

SB

Sofala see MANEKWENI

soilmarks Term used in AERIAL ARCHAEOLOGY

to refer to a type of marking by which the presence of ancient features may be recognized in the bare soil. In some regions, soilmarks have been of great importance in the recognition of archaeological sites in heavily plough-levelled areas – for example the identification of ploughed-out CELTIC FIELDS on the Wessex chalkland by Crawford and Keiller (1928), the discovery of numerous Roman villas in Picardy by Agache (1978) or the identification of prehistoric sites under arable cultivation in the American mid-west (Baker and Gumerman 1981: 16–20, pl.1).

Soilmarks appear as changes in the basic colour of the soil or as apparent changes due to differing soil moisture. Direct soilmarks are due to the exposure of actual archaeological deposits as a result of their partial destruction through cultivation. Examples include the Roman villas recorded in northern France (Agache 1978), seen as masonry where the walls have been freshly clipped by the plough, or the black markings in ploughsoil where charcoal-burning sites have been disturbed. Indirect soilmarks, often dampmarks, derive from

SOIL PHOSPHORUS ANALYSIS 535

the same class of below-ground features as do cropmarks. The variation in the moisture-retaining or evaporation capacities of the buried feature and its surrounding matrix may give rise to variation in the colour of the ploughsoil above. A buried ditch with humic fill will retain moisture after a free-draining subsoil may have dried out (see CROPMARKS). Moisture will evaporate at different rates from materials of different specific heat, producing either positive or negative dampmarks. The use of false-colour infra-red film (see AIRBORNE REMOTE SENSING) can be helpful in enhancing the visibility of marks in bare soil.

O.G.S. Crawford and A. Keiller: Wessex from the air (Oxford, 1928); D.R. Wilson: Aerial reconnaissance for archaeology (London, 1975), 53–69; R. Agache: La Somme pre-Romaine et Romaine (Amiens, 1978); C. Baker and G.J. Gumerman: Remote sensing: archaeological applications of remote sensing in the north central lowlands (Washington, 1981); O. Braasch: Luftbildarchäologie in Süddeutschland

(Stuttgart, 1983).

FG

soil phosphorus analysis The determination of the phosphorus (more specifically, the phosphate) content of soils for site location and interpretation. First applied in the 1930s, the method relies on the fact that there is an enhancement in soil phosphorus concentration at sites of human settlement due to the accumulation of waste products and also the presence of burials. Phosphorus is mainly present in soils as the phosphate anion in both organic and inorganic compounds, the latter including calcium and iron phosphates. Most methods of analysis applied to large surveys have determined only the inorganic content since simpler extraction techniques are required. The phosphorus is usually extracted with dilute acids and determined by COLORIMETRIC ANALYSIS, for example by conversion to a blue complex with ammonium molybdate (molybdenum blue method).

Apart from the potential as a prospecting tool, at a particular site the distribution of phosphate can be used as an aid to the interpretation of features and to determine the limits of occupation. When applied as a surveying technique it is necessary to take samples at regular recorded intervals over the area to be investigated from a consistent soil horizon or excavation context. The spacing of samples may be less than 1 m for intra-site studies or 100 m or more for site location. In both cases large numbers of samples are often involved and consequently rapid methods of analysis have been developed.

D. Gurney: Phosphate analysis of soils: a guide for the field

536 SOIL PHOSPHORUS ANALYSIS

archaeologist (Birmingham, 1985); P. Bethell and I. Máté: ‘The use of soil phosphate analysis in archaeology, a critique’, Scientific analysis in archaeology, ed. J. Henderson (Oxford, 1989), 1–29.

MC

Soleb Religious and funerary site in the 3rd cataract region of Upper Nubia. The site consists primarily of an Egyptian temple dating to the reign of Amenhotep III (c.1391–1353 BC) and a cemetery of the Meroitic period (c.300 BC–AD 350).

M. Schiff Giorgini: Soleb, 2 vols (Florence, 1965–71).

IS

Solutrean (Solutrian) Upper Palaeolithic tool tradition or industry of c.21,000 16,000 BC, characterized by leaf-shaped or ‘foliate’ points. Often superbly finished using pressure retouch or delicate percussion retouch, Solutrean points are among the finest examples of Upper Palaeolithic stone tool technology. The tradition is named after the site of Solutré (Saône and Loire), but largely understood from the phases identified at LAUGERIE-HAUTE rockshelter; the earlier Solutrean is concentrated in southwest France but later Solutrean assemblages appear throughout much of western Europe. The points may be fairly clearly divided into: Proto-Solutrean, marked by the emergence of flat-faced (unifacial) points; Early Solutrean with developed flat-faced points; Middle Solutrean with classic bifacial finely flaked laurelleaf points (during this phase the Solutrean industry increased its geographical range considerably); and final or Late Solutrean with shouldered or notched foliate (or willow-leaf shaped) points. The bone industry is not as varied and developed as in the succeeding MAGDALENIAN, although the later Solutrean is marked by the invention of the perforated needle. The distinction between the latest ‘Solutrean’ and the early ‘Magdalenian’ is a rather artificial construct; the assemblages are often rather similar and increasingly the radiocarbon dates from sites classified into one or the other seem to overlap.

P. Smith: ‘The solutrean culture’, SA 211 (1964), 86–94; R.R. Larick: ‘Circulation of Solutrean foliate points within the Périgord, S.W. France’, The human uses of flint and chert, ed. G. de G. Sieveking and M.H. Newcomer (Cambridge, 1987), 217–30.

RJA

SOM (Seine-Oise-Marne) culture |

|

Late Neo- |

lithic to Early Bronze Age cultural |

complex |

|

of northern France, defined in 1950 |

by Gordon |

|

Childe and Nancy Sandars. Centred on the rivers Seine, Oise and Marne, the group extends into north France generally and has close parallels with the HORGEN CULTURE of Switzerland. It dates from the 3rd millennium BC, and in northern France it succeeds the CHASSÉEN cultural complex of the middle Neolithic. The SOM is defined by the following features: pottery of poor quality – markedly poorer than the undecorated but finely finished Chasséen ceramics – and often in the form of ‘flower-pot’ shaped vessels without lugs or handles; the presence of GRAND PRESSIGNY FLINT; fine flint daggers and barbed and tanged arrowheads; a particular form of notched flint sickleblade (scies-à- encoche); an increase in the number of flint axes; and a range of distinctive jewellery including axeamulets, horn and bone pendants and schist bracelets.

The SOM is associated with distinctive funerary practices. For the first time in the Paris basin, collective burial was practised – with formal funerary monuments such as ALLÉES COUVERTES (megalithic gallery graves), pits and hypogees cut into the chalk. The tombs are sometimes decorated with distinctive anthropomorphic figures.

Although very few SOM settlement sites have been identified (but see Watté 1976), SOM culture sites generally have a more expansive distribution pattern than the Chasséen or earlier Neolithic sites, and the use of more varied soil types and rainfall dependent plateau areas may indicate that the SOM coincides with the introduction of the plough and the use of animals for traction. A limited range of metal objects (copper beads etc.) begin to appear during the SOM period, but these were probably obtained through exchange as there is no evidence of local metallurgy. A few allées couvertes contain early forms of beaker, indicating acceptance of

elements of the BEAKER PHENOMENON.

V.G. Childe and N. Sandars: ‘La civilization de Seine- Oise-Marne’, L’Anthropologie 54 (1950); J-P Watté: ‘L’habitat Seine-Oise-Marne du Grand-Epauville à Montvilliers (Seine-Maritime), BSPF 73 (1976), 196.

RJA

Somerset Levels Area of peat bog in Somerset, England, that has provided the most extensive ‘wetland’ evidence in British archaeology. Although the area is affected by drainage schemes and peat extraction, the waterlogged conditions have helped preserve features such as Neolithic wooden tracks, notably the ‘Sweet Track’. Quickly built of planks and rails raised over the bog to provide a dry walkway about 1800 m long, this track seems to have

been used for about a decade, during which time axe-heads (one of Sussex flint, the other probably from the Alpine region), leaf-shaped arrowheads, and uniquely preserved wooden artefacts (a possible mattock and spades, bows, spoon, paddles etc.) were deposited around the structure. Analysis of the wood used to build the track suggests that, even at this early date, Neolithic farmers were beginning to manage woodlands. A significant attribute of this wetland evidence is that it has begun to yield absolute dates of an extraordinary precision through the use of DENDROCHRONOLOGY – the construction of the Sweet Track has been dated to 3807/3806 BC – for itself and the associated range of Early Neolithic artefacts.

B. Coles and J. Coles: Sweet Track to Glastonbury: The Somerset Levels in prehistory (London, 1986); J.M. Coles: ‘Precision, purpose and priorities in wetland archaeology’, AJ 66/2, 227–47; J. Hillam et al.: ‘Dendrochronology of the English Neolithic’, Antiquity 64 (1990), 210–20.

RJA

Songo Mnara see SWAHILI HARBOUR TOWNS

Son Vi culture Late Pleistocene gathering and hunting culture of northern Vietnam, dated to 18,000–9000 BC. Most of the 60 or so sites identified are found in uplands surrounding the Red River valley, but at CON MOONG cave the ‘Sonviian’ remains were clearly stratified under the HOABINHIAN. Several stone-tool types have been defined, including cobbles with a flaked transverse cutting edge, scrapers, and side choppers where the flaking is found on the lateral side. Since most of the sites were open (as opposed to caves), no biological finds have survived, but at Con Moong cave there is evidence for a broad spectrum of gathering and foraging subsistence within a forested habitat.

Ha Van Tan: ‘The Hoabinhian in the context of Viet Nam’, Vietnamese Studies 46 (1976), 127–97.

CH

Sources de la Seine The source of the river Seine is the find-spot of a rarely preserved series of wooden ex-voto carvings. The 200 or so carvings, of variable but generally rather low quality, represent both whole figures and parts of the body

– such as specific organs, limbs and especially heads. The carvings were probably a means of gaining divine help in the healing of ailments. Associated pottery and dendrochronological evidence suggest that the pieces date from the early 1st century BC.

S. Deyts: Les bois sculptés des sources de la Seine, Éditions

SPANISH LEVANTINE ROCK ART 537

du centre national de la recherche scientifique, XLIIe supplément à ‘Gallia’ (Paris, 1983).

RJA

South Arabian civilization see ARABIA, PRE-

ISLAMIC

Southern Cult (or Southeastern Ceremonial Complex) Term used to refer to the distinctive motifs and artefacts found at some MISSISSIPPIAN sites in eastern North America. Elements of the Southern Cult can be identified over an extended period, although its classic expression occurred in the 13th century AD. The objects were closely associated with high social positions, and were often buried with important people. Many were fashioned from valued non-local materials, including engraved whelk shells and thin copper plates with raised designs. Images such as men in falcon costumes indicated boldness and prowess in war. Skull and bone designs underscored close connections with illustrious ancestors and therefore bolstered claims to leading positions in these societies.

J.A. Brown: ‘The southern cult revisited’, MJA 1 (1976), 115–35; P. Galloway, ed.: The southeastern ceremonial complex (Lincoln, NE, 1989).

GM

Soviet Union see CENTRAL ASIA; CIS AND THE BALTIC STATES

Spanish Levantine rock art Rock art of eastern Spain (i.e. ‘Levantine’ Spain) of the Epipalaeolithic, Mesolithic and early Neolithic. Painted in shallow rockshelters, the art contrasts with the cave art of the Upper Palaeolithic in that it represents complex scenes (including narrative scenes) of men and animals. It is nearly always executed in shades of red or black (but never both together), with occasional paintings in white and some engravings. As a rule, the different techniques seem to represent different bodies, and probably periods, of art.

The style and content of the paintings varies, from archetypal complex scenes of tiny figures (for example, engaged in battle at the rockshelter at Civil, Valltorta, or the detail of a group of hunters apparently executing a man by firing arrows at him at REMIGIA, Castellón) to single animals (the great bull, 1.10 m long at Cuevas de la Araña). In most paintings, figures are nude and are often equipped with bows and arrows. Most often they are shown

538 SPANISH LEVANTINE ROCK ART

hunting, running, dancing in a stylized but lively manner that is quite distinct from the static and schematic art of the Spanish farming Neolithic. Abbé Breuil maintained that part of Spanish Levantine art was Palaeolithic, though this is now discounted by most authorities. It seems more probable that it represents a complex succession of styles from the Epipalaeolithic through a later period in which hunting and gathering peoples existed contemporaneously with agricultural and herding communities on adjacent plains. This would explain why some of the scenes in the art depict the economic activities of hunting and gathering peoples, while others seem to show domesticated animals and digging implements.

A. Beltrán: Rock art of the Spanish Levant (Cambridge, 1982).

RJA

spatial analysis Wide range of statistical techniques applied to a variety of archaeological problems, sharing the need to study the spatial distribution of archaeological objects. The techniques can be divided archaeologically into inter-site and intra-site analyses, and statistically by the nature of

the DATA (see NEAREST-NEIGHBOUR ANALYSIS and

QUADRAT ANALYSIS). The term was introduced into archaeology by Ian Hodder; recent trends have begun to subsume it into GEOGRAPHICAL

INFORMATION SYSTEMS (GIS), but it remains a

body of theory and methodology in its own right.

See also REGRESSION ANALYSIS, SPATIAL AUTOCORRELATION, THIESSEN POLYGONS, TREND SURFACE ANALYSIS. For a critical descrip-

tion of a technique of spatial analysis called

UNCONSTRAINED CLUSTERING see MASK SITE.

I.R. Hodder and C.R. Orton: Spatial analysis in archaeology (Cambridge, 1976); H. Hietala, ed.: Intrasite spatial analysis in archaeology (Cambridge, 1984); H.P. Blankholm: Intrasite spatial analysis in theory and practice

(Aarhus, 1991).

CO

spatial autocorrelation A situation which occurs in statistical analysis when values of a spatial VARIABLE at nearby locations are correlated with each other; this correlation usually decreases as the distance between locations increases. It can cause complications; for example, when using QUADRAT ANALYSIS to study the relationship between two variables, SIGNIFICANCE levels will be adversely affected if either is spatially autocorrelated. It can also be studied in its own right as a simple method of spatial analysis.

A.D. Cliff and J.K. Ord: Spatial autocorrelation (London, 1973); I.R. Hodder and C.R. Orton: Spatial analysis in archaeology (Cambridge, 1976), 174–83.

CO

specific gravity analysis (SG) Method of analysis based on the measurement of the density of a material relative to that of water at 4°C. The measurement is usually made by ‘Archimedes’ principle’ and involves weighing the artefact in air and then in a liquid (usually a high density organic compound). It has been applied to the analysis of gold artefacts such as coins and depends on the higher density of gold compared with the alloying metal e.g. silver. The method is strictly only applicable to binary alloys, i.e. gold-silver or goldcopper.

M.J. Hughes and W.A. Oddy: ‘A reappraisal of the specific gravity method for the analysis of gold alloys’, Archaeometry 12 (1970), 1–11.

MC

speos Type of rock-cut temple or shrine in

Egypt and Nubia (see ABU SIMBEL, BENI HASAN and

GEBEL EL-SILSILA).

Speos Artemidos see BENI HASAN

sphinx (Egyptian: shesep ankh, ‘living image’) Imaginary beast, usually combining the body of a lion with the head of a human being, frequently found in the art and myths of Egypt, the Ancient Near East and Greece. The earliest sphinxes appeared in the iconography of Egypt and Mesopotamia in the early 3rd millennium BC, primarily taking the form of guardian figures. The Great Sphinx at GIZA, regarded as a personification of the god ‘Horus in the horizon’, is the most significant surviving archaeological example.

A. Dessene: Le sphinx: étude iconographique (Paris, 1957); H. Demisch: Die Sphinx (Stuttgart, 1977); M. Lehner: ‘Reconstructing the Sphinx’, CAJ 2/1 (1992), 3–26.

IS

Spirit Cave Small rockshelter with a sequence of deposits dated 11,000–5500 BC, located at an altitude of 650 m on a steep hillside overlooking the Khong Stream in northern Thailand. Excavations by C.F. Gorman from 1966 uncovered a material culture which parallels that from the HOABINHIAN sites in Vietnam, including the late development of polished stone adzes and pottery. Spirit Cave was

the first such site to be subjected to rigorous screening, resulting in a sample of plant remains and microfauna. The former included canarium nuts, butternut, almonds and fruits of a species now used for poisoning arrowheads; animal bones covered a wide spectrum including fish, squirrel, badger, porcupine, deer and a few pig bones. The site thus seems to have been used as a base for broad spectrum foraging.

C.F. Gorman: ‘Excavations at Spirit Cave, North Thailand: some interim impressions’, Asian Perspectives 13 (1972), 79–107.

CH

Spiro Eastern North American site encompassing 11 mounds, located along the Arkansas River in eastern Oklahoma. This Caddoan site is best known for an impressive mortuary deposit in the Craig Mound that contained the remains of many highranking people. Disarticulated bones were found arranged in several ways, such as on litters or in cane baskets. They were accompanied by numerous finely crafted artefacts often made from imported raw materials, including engraved marine shell cups and copper cut-out figures. The site was occupied for many centuries, although the mortuary feature dates to the 14th century AD.

J.A. Brown: ‘Spiro art and its mortuary contexts’, Death and the afterlife in pre-Columbian America, ed. E.P. Benson (Washington, D.C., 1975), 1–32; ––––: The Spiro ceremonial center (Ann Arbor, 1996).

GM

spondylus shell Type of marine bivalve shell with long spines on its exterior which appears in archaeological deposits both in Europe and South America. Ornaments made from the S. gaederopus species frequently appear in Neolithic contexts around the Mediterranean (e.g. SITAGROI in Greece) and central and southeastern Europe (e.g. VARNA in Bulgaria). They are often taken as evidence of trade or exchange networks, particularly in central Europe, since the Mediterranean is the only possible source of the living shellfish. Although this assumption is probably correct, fossil varieties of spondylus can be obtained locally; once these have been worked into an ornament, the difference between fossil shell and Mediterranean shell may only become apparent after geochemical analysis, which excavators in the past have rarely applied.

Two species (S. princeps and S. calcifer) are native to the deep warm waters of the Gulf of Guayaquil and northwards to the Gulf of California. These were much prized by the people of Peru, who traded

STABLE ISOTOPE ANALYSIS 539

to Ecuador for them from the Initial period (2300–1200 BC) onwards.

A. Paulsen: ‘The thorny oyster and the voice of God: Spondylus and Stromus in Andean prehistory’, AA 39 (1974), 597–606; J. Shackleton and H. Elderfield: ‘Strontium isotope dating of the source of Neolithic European Spondylus shell artefacts’, Antiquity 64 (1990), 312–15.

KB/RJA

Sredni Stog Neolithic/Copper Age cultural tradition that existed largely in the forest-steppe interfluve between the Dniepr and the Don. The settlements (unfortified) were located on low river terraces – which were intensely forested at that time. The outstanding feature of the Sredni Stog settlements is that their economy, unusually for the period, included horse-breeding as an important component. In some cases (Dereivka, Molyukov Bogor, Alexandria) the bones of horses make up over 50% of the total faunal remains. The situation of Dereivka (Telegin 1986) is typical. The site is situated on a low terrace of river Omelnik, a tributary of the Dniepr, and covers an area of the c.3000 sq. m. The single cultural layer includes at least three subterranean dwelling structures, and a ritual emplacement comprising a horse skull, a foot and foreparts of two dogs. In all, the faunal assemblage from the site includes the remains of at least 52 horses. Four radiocarbon measurements date the site – attributed by Telegin to the middle stage of the Sredni Stog sequence – to between 3380 and 4570 calendar years BC. Cemeteries were found at Dereivka and at some other Sredni Stog sites; the ochre-covered dead were placed on their backs in a contracted posture in oval-shaped flat graves. In several cases (Yama near Donetsk and Koisug on the lower Don), Stredni Stog burials were placed under burial mounds.

D.Ya. Telegin: Sredn’ostogis’ka kul’tura epohi midi [The Sredni Stog culture of the Copper Age] (Kiev, 1973);

––––: Dereivka, a settlement and cemetery of Copper Age horse keepers on the Middle Dniepr, BAR IS, S267 (Oxford, 1986). M.A. Levine: ‘Dereivka and the problem of horse domestication’, Antiquity 64 (1990), 727–40.

PD

Sri Lanka see ASIA 2; ANURADHAPURA;

POLONNARUVA

stable isotope analysis Measurement of the abundance ratios of stable (i.e. non-radioactive) isotopes of certain elements with applications in provenance, dietary studies and dating.

540 STABLE ISOTOPE ANALYSIS

See CARBON ISOTOPE ANALYSIS, LEADISOTOPE

ANALYSIS and OXYGEN ISOTOPE ANALYSIS.

MC

stakehole Feature produced by the act of driving a wooden stake into the ground. Whereas POSTHOLES are larger and usually consist of a prepared hole, the remains of the post itself (the post pipe’) and sometimes also ‘post packing’, stakeholes simply comprise the hole and fill formed by the point of the stake.

standard deviation In statistical analysis, the term ‘standard deviation’ is one of several ‘measures of dispersion’ of a VARIABLE about its MEAN. In mathematical terms it can be expressed by the equation s2=i(xi – x) 2/n, i.e. it is the square root of the variance, which is the mean of the squared differences between the data values and their mean. The ‘±’ term of an uncalibrated RADIOCARBON DATE is the standard deviation of the estimated date.

J.E. Doran and F.R. Hodson: Mathematics and computers in archaeology (Edinburgh, 1975), 39; C.R. Orton:

Mathematics in archaeology (Glasgow, 1980), 90–4; S. Shennan: Quantifying archaeology (Edinburgh, 1988), 42–4; M. Fletcher and G.R. Lock: Digging numbers (Oxford, 1991), 44–6.

CO

standardized, standardization In statistical analysis, a VARIABLE is said to be standardized if it has been transformed so that it has a zero MEAN and STANDARD DEVIATION of one. Standardization is used in order to compare

BUTIONS with standard distributions given in statistical tables, and to reduce multivariate data to a common scale (see

ANALYSIS). The transformation is sometimes (incorrectly) called NORMALIZATION.

J.E. Doran and F.R. Hodson: Mathematics and computers in archaeology (Edinburgh, 1975), 39; S. Shennan: Quantifying archaeology (Edinburgh, 1988), 105–7, 246; M. Fletcher and G.R. Lock: Digging numbers (Oxford, 1991), 47.

CO

Star Carr Early Mesolithic site, dated to the earlier 9th millennium BC (c.7300 uncalibrated years BC), and used intermittently for perhaps three centuries. It is located about 8 km west of Scarborough in Yorkshire, England. The excavation of the site by Grahame Clark (1949–51) greatly illuminated our understanding of the British

and European Mesolithic; although certain of his interpretations have now been questioned, Clark’s work at Star Carr is regarded as a pioneering example of a multidisciplinary investigation, or, to use Clark’s term, ‘bioarchaeology’.

The main feature of the site was a rough birchwood platform on the edge of a now extinct lake; Clark (1954) believed that this platform formed a living area, although it has been controversially reinterpreted as a mixture of driftwood and debris thrown from the actual (supposedly largely unexcavated) living area (Price 1989). Clark believed the site to have been occupied only in the winter and spring by migratory deer hunters. However, this conclusion was based upon the original faunal analysis (included in Clark’s 1954 excavation report), which has been endlessly reviewed. A comprehensive revision by Legge and Rowley-Conwy (1988), who usefully summarize earlier arguments, concluded that Star Carr was indeed seasonally occupied, but in the late spring and summer, and that the site may have acted as a hunting station from which meat (red and roe deer, elk and aurochs) was transported to a base camp elsewhere.

Star Carr has a particularly rich and wellpreserved antler and bone industry, with many barbed spearheads and digging tools. This and the character of the flint industry (microliths, burins, scrapers etc.) led Clark to suggest that the site was an early variant of the MAGLEMOSIAN complex. However, he also noted a number of idiosyncracies, especially the preference for barbed points made from antler, rather than bone. The most evocative finds were 21 perforated stag frontlets with carefully pared down antlers, which may have been worn as head-dresses during ceremonies (or possibly as disguises during hunts).

J.G.D. Clark: Excavations at Star Carr (Cambridge, 1954); W.F. Libby: Radiocarbon dating, 353 (Chicago, 1955, 2nd edn), 1988; A.K. Legge and P.A. Rowley-Conwy: Star Carr revisited (London, 1988); T.D. Price: ‘Willow tales and dog smoke’, The interpretation of prehistory: essays from the pages of the Quarterly Review of Archaeology, vol. 10/1 (1989), 107–14.

RJA

Starcˇevo (Starcˇevo–Körös–Cris¸) culture

Earliest farming culture of Serbia, named after a site beside the Danube near Belgrade that was partially excavated in the 1930s. Although Starcˇevo farmers cultivated early forms of wheat (especially emmer) and raised sheep, cattle and pig, hunting continued to play a significant part in their economy; faunal remains include red deer, roe deer, wild cattle, horse and boar, game and fish. Incomplete strati-

graphies at Starcˇevo sites (most of the material from Starcˇevo itself came from pits rather than deep stratigraphies) mean that the pottery sequence is not entirely clear. The decoration is relatively crude

in comparison to the succeeding ˇ culture, but

VINCA

is sometimes impressed, incised or, especially in Starcˇevo II, painted. The painted designs are predominantly black motifs on a red slip, in contrast to early Neolithic wares further south in the Balkans and Greece which tend to be white and red. During the Starcˇevo II phase the culture expanded and began to be influenced by other early farming cultures of southeast Europe, such as

and SESKLO. Like other early farming groups, Starcˇevo villages manufactured a range of anthropomorphic and animal figurines.

The neighbouring early farming cultural groupings of Körös in Hungary and Cris¸ in Romania are closely related to the Starcˇevo culture, and are often treated as one complex in the literature (Starcˇevo–Körös–Cris¸ culture). In the case of the Körös culture, the exploitation of marine resources seems to have been even more pronounced, and bones of catfish and pike are often preserved; one site, Röszke-Ludvár, preserved dense layers of fish scales a few centimetres thick, suggesting largescale fish drying and processing. Sheep also seem to form a larger proportion of the faunal assemblages than cattle and pigs – over 50%, like the early farming groups in Greece and the southern Balkans such as Anza – in contrast to the main Starcˇevo–Cris¸ grouping. The Körös culture is often cited as a probable cultural predecessor of the BANDKERAMIK culture. The lithic technology of the Cris¸ culture includes microliths, which are assumed to be a carry-over from the local Mesolithic toolkit. Cris¸ pottery sherds have been found at sites of the BUG-DNIESTRIAN culture to the east, providing interesting evidence of contact between an early farming economy and a late hunting and gathering economy.

V. Fewkes et al.: ‘Excavations at Starcˇevo, Yugoslavia, seasons of 1931 and 1932: a preliminary report’, Bulletin of the American School of Prehistoric Research 9 (1933), 33–54; D. Garašanin Starcevacka kultura (Lljubljana, 1954); R. Tringham: Hunters, fishers and farmers in eastern Europe 6000–3000 BC (London, 1971); M. Garašanin: ‘The Stone Age in the central Balkan area; the Eneolithic period in the central Balkan area’, Cambridge Ancient History III part 1 (Cambridge, 1982), 75–162; A. Whittle: Neolithic Europe: A survey (Cambridge, 1985), 45–6.

RJA

Starosel’ye Palaeolithic cave-site in the Crimea, Ukraine, situated in the valley of Kandy-Dere near

STATISTICAL CYCLE 541

the town of Bakhchisarai. The site was discovered and excavated (1952–6) by A.A. Formozov, and includes a MOUSTERIAN lithic industry. The extended skeleton of a child, 18–20 months old, was found buried in the middle part of one of the lower levels. Several writers (Yakimov and Kharitonov 1979) classify the specimen as an ANATOMICALLY

MODERN HUMAN.

V.P. Yakimov and V.M. Kharitonov: ‘K probleme krymskih neandertal’cev’ [The problem of the Crimean Neanderthals], Issledovanie paleolita v Krymu [Palaeolithic studies in the Crimea], ed. Yu.G. Kolosov (Kiev, 1979), 60–2.

PD

statistical cycle A model of the way in which archaeologists interact with their material in a research setting. It formalizes the stages by which archaeologists relate their ideas to evidence from excavations and other fieldwork, by contrasting the world of THEORY with the real world represented by DATA (see Fig.49). It sees the relationship between the two as mediated through MODELS, which vary considerably in their complexity and expression. It does not constrain an archaeologist to any particular paradigm of research, e.g.

HYPOTHETICO-DEDUCTIVE or INDUCTIVE, since

the cycle may be entered at any point. It encompasses the four main ways in which archaeologists

use statistics – EXPLORATORY DATA ANALYSIS,

DATA REDUCTION, PARAMETER ESTIMATION and

|

|

Mathematical |

Research |

|||||||||||

|

|

analysis |

|

|

|

design |

||||||||

|

|

model |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||

|

|

building |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

models and |

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

deductions |

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

theory |

|

|

|

Statistical |

|

|

|

real |

|

||||

|

|

|

|

Idealization |

|

|

|

world |

|

|||||

|

hypotheses |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

data |

|

|||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

provisional |

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

conclusions |

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

about models |

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

archaeological statistical judgement and analysis

interpretation

Figure 49 statistical cycle Flow chart illustrating the concept of the statistical cycle (drawn by Clive Orton).

542 STATISTICAL CYCLE

HYPOTHESIS TESTING. It can also accommodate subjective (BAYESIAN) approaches as well as the more common objective approaches.

J.E. Doran and F.R. Hodson: Mathematics and computers in archaeology (Edinburgh, 1975), 343–6; C.R. Orton:

Mathematics in archaeology (Glasgow, 1980), 19–24.

CO

statistical distribution In statistical analysis of archaeological DATA, a ‘distribution’ is a mathematical model of the behaviour of one (or more) VARIABLE(S), e.g. how frequently its value is likely to exceed certain limits. For example, it is believed that an uncalibrated RADIOCARBON DATE has a NORMAL DISTRIBUTION. A distribution may be based on observations (empirical distribution) or theoretical consideration. The form of a distribution depends on its PARAMETERS, of which there may be one, two or more (e.g. MEAN, STANDARD DEVIATION). One object of statistical analysis is to estimate the parameters of such distributions; another is to test whether a particular distribution is an appropriate description of a particular DATASET (see GOODNESS-OF-FIT). When a distribution

cannot be found to fit a dataset, NON-PARAMETRIC STATISTICS must be used.

J.E. Doran and F.R. Hodson: Mathematics and computers in archaeology (Edinburgh, 1975), 39–50; S. Shennan: Quantifying archaeology (Edinburgh, 1988), 33–44.

CO

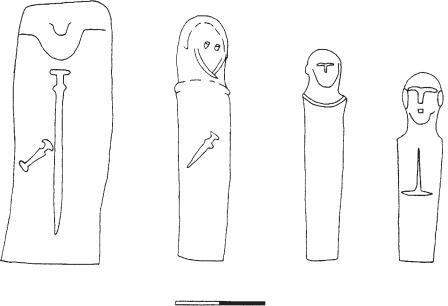

statue-menhir Term applied in European prehistory to any standing stone or ‘menhir’ that has been carved into a simple anthropomorphic form. Statue-menhirs are concentrated in southern France and Corsica, Sardinia and Italy, with some examples in northwest Europe, notably western France and the Channel Islands; they were largely erected from the later 3rd millennium BC into the 2nd millennium BC. Corsica has the most impressive concentrations, notably at FILITOSA and Pagliaiu. Here, the more elaborate examples may be 2–3 m high, with a distinct head and simplified facial features, and daggers and swords in bas-relief; a few may once have had horns attached to their heads, and all appear to be male (see Whitehouse 1981 for typological summary).

The statue-menhirs of the Alpine region of north Italy, for instance at Val Camonica, are very

A |

B |

C |

D |

0 |

|

1 m |

|

Figure 50 statue-menhir Corsican statue-menhirs: (A) Filitosa V, (B) Nativu, (C) Barbaggiu, (D) Filitosa IV (drawn by Philip Howard). Source: R. Whitehouse: ‘Megaliths of the Central Mediterranean’, The megalithic monuments of Western Europe, ed. C. Renfrew (London, 1981), fig. 9.

schematic, and often anthropomorphized simply by the addition of a belt or collar and sometimes a weapon. The group is related to the statue-menhirs found in Switzerland at Petit Chasseur. Some of the statue-menhirs from the group in northwest Tuscany are similar, although more examples depict breasts; here there is also a later, more elaborate and exclusively male group, displaying a larger array of weapons. A few low slabs carved with breasts and necklaces etc., occur in southern Italy on the edge of the Tavoliere plain.

Some early MEGALITHIC art associated with the Neolithic chamber tombs of France is similar to the later corpus of statue menhirs, in that it depicts schematic human figures and weapon motifs on megaliths; there is also evidence from Gavrinis that the builders may have used re-used earlier carved menhirs in the building of the tomb. Representations of pairs of breasts, often with necklaces, also occur frequently on megaliths that form part of the allées couvertes of western and northcentral France.

J. Armal: Les statues-menhirs, hommes et dieux (Toulouse, 1976); R. Whitehouse: ‘Megaliths of the central Mediterranean’, The megalithic monuments of Western Europe, ed. C. Renfrew (London, 1981), 42–63; R. Joussaume: Dolmens for the Dead, trans. A. and C. Chippindale (London, 1988), 116–23, 141–2.

RJA

STEMMED POINT TRADITION 543

generally roughly rectangular in shape, with plain, painted, inscribed and/or sculpted surfaces.

In Mesopotamia, there were many different forms of stelae: from at least the Uruk period (c.4300–3100 BC) onwards, rulers placed votive stelae in temples in order to inform the gods of their achievements. In later times (particularly in the Kassite period, c.1600–1100 BC) the KUDURRU, or boundary stone, was used to record land transfers. In pharaonic Egypt, the so-called ‘false-door stele’, often incorporating lists of funerary offerings and relief depictions of the deceased, was a focal point of the private tombs of the elite from the 3rd Dynasty (c.2686–2613 BC) onwards.

The Mesoamerican stele, dating from Preclassic to Postclassic times (2500 BC–AD 1521), was most typically associated with the Classic period LOWLAND MAYA. Sometimes decorated with human figures, glyphs and ‘long count’ dates, the Mesoamerican stele was erected in a plaza, usually in front of a pyramidal structure (and often paired with an accompanying altar).

I. Graham and E. Von Euw: Corpus of Maya hieroglyphic inscriptions (Cambridge, MA, 1975–) [ongoing multivolume series]; S. Wiebach: Die ägyptische Scheintür (Hamburg, 1981) [the Egyptian false-door stele]; I.J. Gelb, P. Steinkeller and R.M. Whiting: Earliest land tenure systems in the Near East: ancient kudurrus (Chicago, 1991).

IS/PRI

Steep Cliff Cave Rockshelter in the limestone uplands of northern Thailand, which contained a thick midden of animal bones and other deposits, dated to 5500–3500 BC. The material culture includes many of the unifacial discoids typical of the Vietnamese HOABINHIAN stone industry. The shelter is on a precipitous slope, some distance from the nearest water source. A forested habitat is evidenced by the bones of macaques, langur monkeys and the Himalayan striped squirrel, but most bones come from large bovids and deer, and the remains of tiger and leopard are also present. It has been suggested that the site was a location for the drying and processing of animal carcases, because the bones have been subjected to much battering, and many have been burned. Screening during excavation led to the recovery of canarium and almond shells, pepper vine seeds and bamboo remains.

CH

stela. stele Slab of stone or wood bearing inscriptions or depictions, usually of a funerary, votive, commemorative or liminal nature, although these four categories may often overlap. Stelae are

Stemmed Point Tradition Early cultural tradition (c.8500–6000 BC) found in many sites between the Rocky Mountains and the Coast- Cascade-Cordilleran range in Western North America (Carlson 1983: 75–83). This tradition is based on the distribution of similar stemmed projectile points and chipped stone crescents in sites extending southwards from southeast British Columbia to interior Oregon, Nevada, and California, which co-occur with older landforms. Regional variations are the LIND COULEE and Windust phases of Washington, the Pluvial Lakes Tradition of Oregon, and the Lake Mojave Complex of Nevada and California. Binary comparisons were used by Rice (1972) to demonstrate the validity of the Windust phase. The functional groupings of artefact categories, based on their association with occupational features, indicated that most assemblages were associated with hunting. This tradition occupies the same territory as the western FLUTED POINT TRADITION and is probably a derivative of it (Carlson 1988). See map 8 (p. 44).

D.G. Rice: The Windust phase in Lower Snake River prehistory (Pullman, 1972); R.L. Carlson: ‘The far west’, Early man in the New World, ed. R.S. Shutler (Beverly

544 STEMMED POINT TRADITION

Hills, 1983), 73–96; ––––: ‘The view from the North’,

Early human occupation in far western North America: the Clovis-Archaic interface, ed. J.A. Willig, C.M. Aikens and J.L. Fagan (Carson City, 1988), 319–24; ––––: ‘Cultural antecedents’, Handbook of North American Indians VII, ed. W. Suttles (Washington, 1990), 60–9.

RC

Stentinello Settlement site on Sicily near Syracuse which has given its name to an elaborate early pottery tradition and associated cultural assemblage that spread over Sicily and Calabria in the late 6th and early 5th millennium BC (Middle Neolithic). The site of Stentinello itself is known mainly from the excavation of the rich deposits in its defensive rock-cut ditch – a common feature of ‘Stentinello’ villages; the internal layout of the village is not clear. The pottery differs from the pre-Stentinello wares in the relatively fine texture of its dark-coloured fabric, the range of forms (gourd-shaped vessels with necks of varying length, cups and large lipped bowls), and especially in its fine decoration. Like many early Neolithic decorated wares, the repeated geometric patterns (zig-zags, circles) seem to be inspired by textiles, although there is also a double motif resembling a pair of eyes; the decoration is usually impressed or incised with occasional white inlay. Stentinello pottery is often regarded as part of the early impressed ware family of pottery styles, although it is perhaps better regarded as having developed from this group.

RJA

Sterkfontein One of several localities close to Krugersdorp, Transvaal, South Africa, to have yielded fossil remains of AUSTRALOPITHECUS AFRICANUS, and, additionally, HOMO HABILIS, the latter associated with ACHEULEAN artefacts. The fossils and artefacts are contained in breccia deposits filling solution cavities developed along ancient fracture lines in pre-Cambrian dolomite. More than 500 australopithecine specimens are recorded from Member 4, estimated, on faunal grounds, to be between 2.8 and 2.4 million years old. The overlying Member 5, with Homo habilis and Acheulean artefacts is faunally dated to between 2 million years (lower levels) and 1 million years ago. Deeper Members (1, 2, and 3) contain fossils which could be as old as 3.6 to 6.5 million years: these still await detailed investigation.

E.S. Vrba: ‘Early hominids in southern Africa: updated observations on chronological and ecological background’,

Hominid evolution, past, present and future. ed. P.V. Tobias

(New York, 1985), 195–200; M.J. Wilkinson: ‘Lower lying and possibly older fossiliferous deposits at Sterkfontein’,

Hominid evolution, past, present and future. ed. P.V. Tobias (New York, 1985), 165–70; R.J. Clarke: ‘Habiline handaxes and paranthropine pedigree at Sterkfontein’, WA 20 (1988), 1–12.

RI

Stichbandkeramik see STROKE-

ORNAMENTED WARE

Stiftmosaik (cone mosaic) Type of wall decoration used in Mesopotamian temples during the URUK and JEMDET NASR periods (c.4000–2900 BC); it consisted of colourful geometrical (and later figurative) designs produced by covering walls and columns with thousands of painted clay or stone cones, perhaps imitating textile wall-hangings.

H. Frankfort: The art and architecture of the ancient Orient, 4th edn (Harmondsworth, 1970), 24–5, figs 8–9.

IS

Stillbay Small holiday resort located 270 km east of Cape Town, which was designated the type-site of the Stillbay MSA (Middle Stone Age) industry in 1929. The artefacts were surface finds on high ground overlooking the sea. The site is undated but may equate with Middle Stone Age II at KLASIES

RIVER MOUTH CAVES.

A.J.H. Goodwin and C. van R. Lowe: ‘The Stone Age cultures of South Africa’, Annals of the South African Museum 27 (1929) 127–9.

RI

stirrup bottle Very common ceramic form in northern Peru, which is also found sporadically in most Native American and one Zaire/Congolese culture. It consists of a closed body with a tubular handle in the form of an up-ended U with a spout in the middle, thus forming handle and spout in one.

stomion see THOLOS

stone-bowl cultures see PASTORAL

NEOLITHIC

stone circles Circular or subcircular arrangements of MEGALITHS, usually free-standing, built from the later 4th millennium BC. The most famous examples are from the Neolithic and Bronze Age in Britain – although there are significant examples of the same periods in Ireland, France (Brittany) and