Supplement A3: The Chemistry of Double-Bonded Functional Groups. Edited by Saul Patai Copyright 1997 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

ISBN: 0-471-95956-1

CHAPTER 25

Biological activity of organic compounds elicited by the introduction of double bonds

ASHER KALIR

Department of Physiology and Pharmacology, Sackler Faculty of Medicine, Tel Aviv University, Tel Aviv 69978, Israel

Fax: 9723-631-3716

and

HENRY H. KALIR

Department of Histology and Cell Biology, Sackler Faculty of Medicine,

Tel Aviv University, Tel Aviv 69978, Israel and Department of Psychiatry, Ichilov Hospital, Tel Aviv, Israel

e-mail: hkalir@post-tauac.il

I. INTRODUCTION . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . |

1617 |

II. COMPARISON OF TOXICITY OF SATURATED AND |

|

UNSATURATED COMPOUNDS . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . |

1618 |

III. UNSATURATED COMPOUNDS OF PHARMACOLOGICAL |

|

INTEREST . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . |

1621 |

IV. DETECTION AND LOCALIZATION OF DOUBLE BONDS . . . . . . . |

1622 |

V. REFERENCES . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . |

1623 |

I. INTRODUCTION

Many aspects of the characteristics of the double-bonded functional groups have been reviewed in an impressive series of treatises, published over a period of more than 30 years. These reviews cover mostly the physicochemical aspects of double bonds: electrophilic additions to carbon carbon double bonds1, directing and activating effects of doubly bonded groups2 etc.

1617

1618 |

Asher Kalir and Henry H. Kalir |

The review ‘Double bonds from a biochemical perspective’3 summarizes the importance of the biochemical reactions of selected groups of physiologically active unsaturated compounds, e.g. those that react with the amino groups of amino acids, polyunsaturated fatty acids and vitamin A.

II. COMPARISON OF TOXICITY OF SATURATED AND

UNSATURATED COMPOUNDS

The purpose of the present paper is to compare the toxicity and pharmacology of saturated compounds with their unsaturated analogs (wherever possible) and to list some important, physiologically active substances, bearing one or more double bonds.

TABLE 1. Hydrocarbons

Saturated |

|

|

Toxicity |

Unsaturated |

Toxicity |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Ethane5 |

narcotic in high concn. |

Ethylene6 |

950,000 ppma |

||

Propane7 |

narcotic in high concn. |

Propylene4 |

asphyxiant |

||

Butane8 |

narcotic in high concn. |

1-Butene9 |

asphyxiant |

||

|

|

|

|

1,3-Butadiene10 |

250,000 ppmb |

|

|

|

|

Isoprene11 |

0.144 mg/lc |

Cyclopentane12 |

38,000 ppma |

Cyclopentene13 |

2.14 g/kgd |

||

Cyclohexane14 |

0.06 |

|

0.07 mg/la |

Cyclohexene15 |

300 ppme |

|

|||||

Ethylbenzene16 |

5.46 |

g/kgd |

Styrene17 |

0.09 g/kgf |

|

Propylbenzene18 |

6.04 |

g/kgd |

Allylbenzene19 |

3.6 g/kgd |

|

Diethylbenzene20 |

1.2 g/kgd |

Divinylbenzene19 |

4.04 g/kgd |

||

a LC (lethal concentration) for mice in air.

b LC for rabbits in air. c LD50 for mice in air. d LD50 for rats (oral).

e Permissible exposure limit. f LD50 for mice (iv).

TABLE 2. Halides

Saturated |

|

Toxicity |

Unsaturated |

Toxicity |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Ethyl chloride21 |

0.18 |

g/la |

Vinyl chloride22 |

47,660 ppma |

|

(irritating, topical anaesthetic) |

|

|

|

|

|

1,2-Dichloroethane13 |

0.97 |

g/kgb |

1,2-Dichloroethene(trans)23 |

1.28 |

g/kgb |

1,1,2-Trichloroethane13 |

0.84 |

g/kgb |

1,1,2-Trichloroethane13 |

7.33 |

g/kgb |

1-Propyl chloride24 |

LD100 > 3 g/kgc |

Allyl chloride25 |

0.7 g/kgb |

||

Isopropyl chloride24 |

potent anaesthetic |

|

|

|

|

1,2-Dichloropropane13 |

2.2 g/kgb |

2,3-Dichloro-1-propene16 |

0.39 |

g/kgb |

|

1-Butyl chloride26 |

2.67 |

g/kgb |

1-Chloro-2-butene27 |

irritating |

|

Ethyl bromide28 |

16,200 ppm (1 h)a |

Vinyl bromide24 |

0.5 g/kgb |

||

1,2-Dibromoethane29 |

0.22 |

g/kgc |

1,2-Dibromoethene30 |

0.117 g/kgb |

|

a LC (lethal concentration) for mice in air. b LD50 for rats (oral).

c LD50 for mice (ip).

25. Biological activity of organic compounds elicited by double bonds |

1619 |

As E. E. Sandmeyer stated, ‘in general, diunsaturation increases the toxicity’4. This is also true, although with some exceptions, for mono-unsaturation.

The toxicity evaluations of the various compounds were carried out on various animals. The most common test was the LD50 (the dose needed to produce the death of 50% of all tested animals) orally in rats. Cases where other animals or other conditions were applied, will be so noted.

Tables 1 9 present a listing of various groups of saturated compounds and of their analogs, bearing a double bond. Table 9 includes several hydroxy and keto derivatives (RCHOH vs RCDO).

As a rule the unsaturated analogs are more toxic. There are some exceptions: diethylbenzene20 and divinylbenzene19 (Table 1), 1,1,2-trichloroethane13 and 1,1,2-trichloroethy- lene13 (Table 2), 2-propanol25 and acetone16 (Table 9) etc.

TABLE 3. Alcohols

|

Saturated |

Toxicity |

Unsaturated |

Toxicity |

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Ethanol31 |

10.6 g/kga |

|

|

|

|

|

1-Propanol26 |

1.87 g/kga |

Allyl alcohol25 |

0.064 g/kga |

||

|

2-Propanol25 |

5.8 g/kga |

|

|

|

|

|

1-Butanol32 |

4.36 g/kga |

|

|

|

|

|

2-Butanol26 |

6.48 g/kga |

Crotyl alcohol16 |

0.79 g/kga |

||

|

a LD50 for rats (oral). |

|

|

|

|

|

TABLE 4. Aldehydes and ketones |

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

||

Saturated |

Toxicitya |

|

Unsaturated |

Toxicitya |

||

Propionaldehyde32 |

1.4 g/kg |

Acrolein32 |

0.046 g/kg |

|||

Butyraldehyde32 |

5.89 g/kg |

Crotonaldehyde33 |

0.3 g/kg |

|||

Methyl ethyl ketone16 |

5.52 g/kg |

Methyl vinyl ketone34 |

0.035 g/kg |

|||

a LD50 for rats (oral). |

|

|

|

|

|

|

TABLE 5. Acids |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

Saturated |

Toxicity |

|

Unsaturated |

Toxicity |

||

|

|

|

|

|||

Propionic acid16 |

4.29 g/kga |

Acrylic acid16 |

2.59 g/kga |

|||

Butyric acid26 |

8.79 g/kga |

Crotonic acid33 |

1.0 g/kga |

|||

Valeric acid35 |

1.29 g/kgb |

2-Methyl-2-butenoic acid |

|

|

||

Isovaleric acid35 |

1.12 g/kgb |

cis36, |

trans37 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

(found in plants) |

|

|

|

Stearic acid35 |

0.022 g/kgb |

Oleic acid35 |

0.23 g/kgb |

|||

a LD50 for rats (oral). b LD50 for mice (iv).

1620 |

|

|

|

Asher Kalir and Henry H. Kalir |

|

|

||

|

TABLE 6. |

Esters |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Saturated |

|

Toxicitya |

Unsaturated |

Toxicitya |

|||

|

Ethyl formate38 |

4.3 |

g/kg |

Vinyl formate38 |

2.82 g/kg |

|||

|

Propyl formate38 |

3.98 |

g/kg |

Allyl formate38 |

0.124 g/kg |

|||

|

Ethyl acetate38 |

5.6 |

g/kg |

Vinyl acetate38 |

2.92 g/kg |

|||

|

n-Propyl acetate38 |

9.37 |

g/kg |

Allyl acetate38 |

0.142 g/kg |

|||

|

Isopropyl acetate38 |

3.0 |

g/kg |

Isopropenyl acetate38 |

3.0 g/kg |

|||

|

n-Propyl butyrate38 |

15.0 |

g/kg |

Allyl butyrate38 |

0.25 g/kg |

|||

|

Ethyl benzoate26 |

6.48 |

g/kg |

Vinyl benzoate38 |

3.25 g/kg |

|||

|

Diethyl succinate32 |

8.53 |

g/kg |

Diethyl fumarate16 |

1.78 g/kg |

|||

|

a LD50 for rats (oral). |

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

TABLE 7. Amines |

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Saturated |

|

Toxicitya |

Unsaturated |

Toxicitya |

|

|

|

|

1-Propylamine16 |

0.57 g/kg |

1-Allylamine39 |

0.106 g/kg |

|||

|

|

Isopropylamine32 |

0.52 g/kg |

|

|

|

||

|

|

Dipropylamine16 |

0.93 g/kg |

Diallylamine16 |

0.65 g/kg |

|||

|

|

Diisopropylamine26 |

0.77 g/kg |

|

|

|

||

|

|

Tripropylamine39 |

0.096 g/kg |

Triallylamine39 |

1.31 g/kg |

|||

|

|

a LD50 for rats (oral). |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

TABLE 8. |

Ethers |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Saturated |

|

Toxicity |

Unsaturated |

Toxicity |

|||

|

|

|

|

|

||||

|

Diethyl ether40 |

2.53 g/kgb |

Ethyl vinyl ether13 |

6.22 g/kgb |

||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

Divinyl ether41 |

51,233 ppma |

|

|

Allyl ethyl ether26 |

14.53 g/kgb |

Allyl vinyl ether40 |

0.55 g/kgb |

||||

|

Di-n-propyl ether42 |

|

|

Diallyl ether40 |

0.26 g/kgb |

|||

a LC (lethal concentration) for mice in air. b LD50 for rats (oral).

TABLE 9. Alcohols vs keto compounds

Saturated |

Toxicitya |

Unsaturated |

Toxicitya |

|||

Ethanol31 |

10.6 g/kg |

Acetaldehyde32 |

1.93 |

g/kg |

||

1-Propanol26 |

1.87 |

g/kg |

Propionaldehyde32 |

1.4 |

g/kg |

|

2-Propanol25 |

5.8 g/kg |

Acetone16 |

8.43 |

g/kg |

||

1-Butanol32 |

4.36 |

g/kg |

Butyraldehyde32 |

5.89 |

g/kg |

|

2-Butanol26 |

6.48 |

g/kg |

2-Butanone16 |

5.52 |

g/kg |

|

Cyclohexanol16 |

1.98 g/kg |

Cyclohexanone13 |

1.53 g/kg |

|||

Benzyl alcohol32 |

3.1 g/kg |

Benzaldehyde18 |

1.3 |

g/kg |

||

Phenethyl alcohol18 |

1.79 |

g/kg |

Acetophenone25 |

0.9 |

g/kg |

|

a LD50 for rats (oral).

25. Biological activity of organic compounds elicited by double bonds |

1621 |

III. UNSATURATED COMPOUNDS OF PHARMACOLOGICAL INTEREST

A significant number of unsaturated compounds are biologically active and known as drugs, agricultural materials etc.

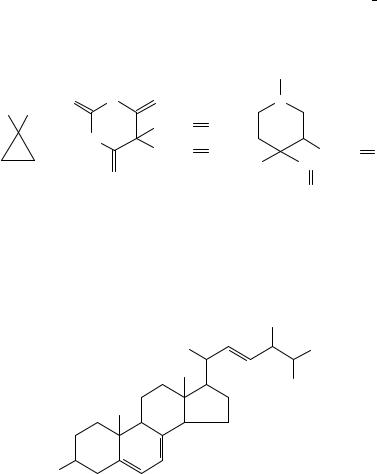

Ethylene6 (CH2DCH2, Table 1) has been found to exert major effects on plant growth and development43. The ethylene precursor in plants is 1-aminocyclopropane- 1-carboxylic acid44 (1). Much attention is given to the carcinogenic45,46 1,3-butadiene10 (CH2DCH CHDCH2, Table 1), an important starting material for synthetic rubbers. Its carcinogenicity is due to the action of its metabolites, the butadiene oxides46 48. Its 2-methyl analog, isoprene10 (CH2DCMe CHDCH2, Table 1), is also carcinogenic49. Interestingly, isoprene is produced in nature by Gram-negative and Gram-positive bacteria50.

|

H |

|

Me |

|

O |

|

|

O |

N |

N |

|

HOOC NH2 |

|

|

|

|

HN |

CH2 CH CH2 |

|

|

CH2 CH CH2 |

|

|

|

|

CH2 CH CH2 |

|

|

O |

Ph |

OCCH2 CH3 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

O |

(1) |

|

(2) |

(3) |

Other examples include allicin51, CH2DCHCH2S(O)CH2CHDCH2, which is an antibacterial; allyl substituted substances like allobarbital (2)52 are sedatives; allylprodine

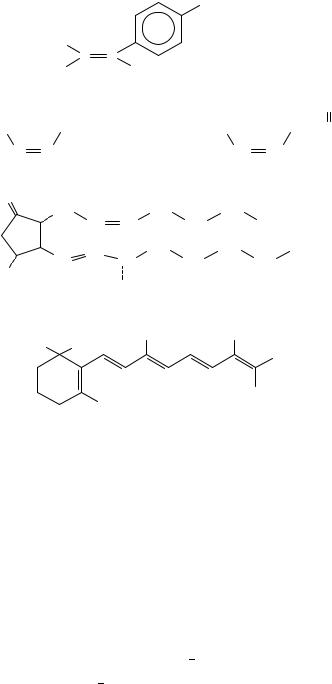

(3)53 is a narcotic analgesic; ergosterol (4)54 is an antirachitic vitamin; toremiphene (5)55 is an antineoplastic; undecylenic acid (CH2DCH(CH2)8COOH)56 is an antifungal; hexalure

(6)57 and muscalure (7)58 are insect attractants.

CH3

CH3 |

CH3 |

CH3

CH3

CH3

HO

(4)

Prostaglandins59, like prostaglandin E2 (8), are implicated in many physiological and pharmacological functions of living organisms. Another very interesting group of naturally occurring polyunsaturated compounds are retinoids (9) that include vitamin A (9, XDCH2OH, YDH). All these are involved in many essential physiological processes, e.g. vision, reproduction etc. Recently they were found to inhibit carcinogenesis. Their activity is summarized in a number of books and reviews60,61.

1622 |

Asher Kalir and Henry H. Kalir |

|

|||

|

|

|

|

OCH2 CH2 N(CH3 )2 |

|

|

Ph |

|

|

|

|

|

|

C |

C |

|

|

ClCH2 CH2 |

|

Ph |

|

|

|

|

|

|

(5) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

O |

CH3 (CH2 )7 |

(CH2 )12 CH3 |

CH3 (CH2 )7 |

(CH2 )6 CCH3 |

||

CH CH |

|

|

CH |

CH |

|

(6) |

|

|

|

|

(7) |

O |

|

|

|

|

|

|

CH2 |

|

CH2 |

CH2 |

|

|

|

CH |

CH |

CH2 |

COOH |

|

|

CH |

CH2 |

CH2 |

CH3 |

|

CH |

CH |

CH2 |

CH2 |

|

HO |

|

||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

OH |

|

|

|

|

|

(8) |

|

|

CH3 |

|

CH3 |

CH3 |

CH3 |

|

|

|

|

X |

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

Y

CH3

(9)

The presence of double-bonded fatty acids in proteins and their isomerization was found to help some bacteria to adapt to ambient temperature changes62. The alteration of CDC bonds in liposomes plays a role in protection against radiation-induced damage63.

IV. DETECTION AND LOCALIZATION OF DOUBLE BONDS

There are numerous methods for detection and localization of double bond(s) in polyunsaturated compounds64. Recent papers mention derivatization and further detection, usually by GC/MS. The reagents used are 2,2-dimethyl-2-aminoethanol (Me2C(NH2)CH2OH) for conversion to oxazolines in nearly quantitative yield65, oxidation with potassium permanganate66, ozonization67 and reduction with hydrazine and subsequent reaction with dimethyl disulfide68.

V.REFERENCES

1.G. H. Schmid and D. G. Garratt, in The Chemistry of Double-bonded Functional Groups: Supplement A1 (Ed. S. Patai), Wiley, London, 1977, pp. 725 912.

2.M. Charton, in The Chemistry of Double-bonded Functional Groups: Supplement A2 (Ed. S. Patai), Wiley, Chichester, 1989, pp. 239 298.

25. Biological activity of organic compounds elicited by double bonds |

1623 |

3.A. H. Mehler, in The Chemistry of Double-bonded Functional Groups: Supplement A2 (Ed.

S. Patai), Wiley, Chichester, 1989, pp. 299 344.

4. E. E. Sandmeyer, in Patty’s Industrial Hygiene and Toxicology, 3rd ed., Vol. 2B (Eds.

G. D. Clayton and F. E. Clayton), Wiley, New York, 1981, pp. 3175 3220.

5.S. Budavari (Ed.), Merck Index, 11th ed., Merck, Rahway, NJ, 1989, p. 588 (No. 3676).

6.F. Flury, Arch. Exp. Pathol. Pharmacol., 138, 65 (1928); S. Budavari (Ed.), Merck Index, 11th ed., Merck, Rahway, NJ, 1989, p. 597 (No. 3748).

7.S. Budavari (Ed.), Merck Index, 11th ed., Merck, Rahway, NJ, 1989, p. 1239 (No. 7809).

8.S. Budavari (Ed.), Merck Index, 11th ed., Merck, Rahway, NJ, 1989, p. 231 (No. 1507).

9.M. L. Smith and G. H. Hanson, Oil, Gas J., 44, 119 (1945); Chem. Abstr., 39, 3783 (1945).

10.C. P. Carpenter, C. B. Shafter, C. S. Weil and H. F. Smyth, J. Ind. Hyg. Toxicol., 26, 69 (1944).

11.V. D. Gostinski, Gigiena Truda i Prof. Zabolevaniya, 9, 36 (1965); Chem. Abstr., 62, 15338a (1965).

12.W. S. Spector, Handbook of Toxicology, Vol. 1, Saunders, PA, 1950, pp. 330 331.

13.H. F. Smyth, Jr., C. P. Carpenter, C. S. Weil, V. C. Pozzani, J. A. Striegel and J. S. Nycum, Am. Ind. Hyg. Assoc. J., 30, 470 (1969).

14. E. Browning, Toxicity and Metabolism of Industrial Solvents, Elsevier, New York, 1965,

pp. 130 134.

15.Anon., NY Dept. of Health Fact Sheet, May 1986.

16.H. F. Smyth, C. P. Carpenter, C. S. Weil, U. C. Pozzani and J. A. Striegel, Am. Ind. Hyg. Assoc. J., 23, 95 (1962).

17.W. J. Meyer and R. Kretzschmer, Arzneim.-Forsch., 19, 617 (1969).

18.P. M. Jenner, E. C. Hagan, J. M. Taylor, E. L. Cook and O. G. Fitzhvg, et al., Food Cosmet. Toxicol., 2, 327 (1964).

19. |

E. E. Sandmeyer, |

in |

Patty’s |

Industrial |

Hygiene |

and |

Toxicology |

(Eds. |

G. D. Clayton |

and |

||

|

F. E. Clayton), 3rd ed., Vol. 2B, Wiley, New York, 1981, pp. 3221 |

|

|

3251. |

|

|

||||||

|

|

|

|

|||||||||

20. |

E. E. Sandmeyer, |

in |

Patty’s |

Industrial |

Hygiene |

and |

Toxicology |

(Eds. |

G. D. Clayton |

and |

||

F. E. Clayton), 3rd ed., Vol. 2B, Wiley, New York, 1981, pp. 3253 3431.

21.M. M. Troshina, Toksikol. Novykh Prom. Khim., 6, 45 (1964); Chem. Abstr., 63, 17017 (1964).

22.L. Prodan, I. Suciu, V. Pislaru, E. Ilea and L. Pascu, Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci., 246, 154 (1975).

23.K. J. Freundt, G. P. Liebaldt and E. Lieberwirth, Toxicology, 7, 141 (1977).

24.T. R. Torkelson and V. K. Rowe, in Patty’s Industrial Hygiene and Toxicology (Eds. G. D. Clayton and F. E. Clayton), 3rd ed., Vol. 2B, Wiley, New York, 1981, pp. 3433 3601.

25.H. F. Smyth and C. P. Carpenter, J. Ind. Hyg. Toxicol., 30, 63 (1948).

26.H. F. Smyth, C. P. Carpenter, C. S. Weil and U. C. Pozzani, Arch. Ind. Hyg. Occup. Med., 10, 61 (1954).

27.S. Budavari (Ed.), Merck Index, 11th ed., Merck, Rahway, NJ, 1989, p. 329 (No. 2130).

28.E. H. Vernot, J. D. MacEven, C. C. Haun and E. R. Kinkhead, Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol., 42, 417 (1977).

29.G. W. Fischer, F. Riemer and S. Gruettner, J. Prakt. Chem., 320, 133 (1978).

30.S. Budavari (Ed.), Merck Index, 11th ed., Merck, Rahway, NJ, 1989, p. 14 (No. 85).

31.G. S. Wiberg, H. L. Trenholm and B. B. Coldwell, Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol., 16, 718 (1970).

32.H. F. Smyth, C. P. Carpenter, C. S. Weil and U. C. Pozzani, Arch. Ind. Hyg. Occup. Med., 4, 119 (1951).

33.H. F. Smyth and C. P. Carpenter, J. Ind. Hyg. Toxicol., 26, 269 (1944).

34.A. S. Martirosyan, Mater. Itogovoy Nauch. Konf. Vop. Gig. Tr. Prof. Patol., 113 (1966); Chem. Abstr., 72, 124809 (1970).

35.L. Oro and A. Wretlind, Acta Pharmacol. Toxicol., 18, 141 (1951).

36.S. Budavari (Ed.), Merck Index, 11th ed., Merck, Rahway, NJ, 1989, p. 102 (No. 678).

37.S. Budavari (Ed.), Merck Index, 11th ed., Merck, Rahway, NJ, 1989, p. 1486 (No. 9365).

38. E. E. Sandmeyer and C. J. Kirwin, in Patty’s Industrial Hygiene and Toxicology, (Eds.

G.D. Clayton and F. E. Clayton), 3rd ed., Vol. 2A, Wiley, New York, 1981, pp. 2259 2412.

39.R. R. Beard and J. T. Noe, in Patty’s Industrial Hygiene and Toxicology (Eds. G. D. Clayton and

F.E. Clayton), 3rd ed., Vol. 2B, Wiley, New York, 1981, pp. 3135 3173.

40. C. J. Kirwin and E. E. Sandmeyer, in Patty’s Industrial Hygiene and Toxicology (Eds.

G. D. Clayton and F. E. Clayton), 3rd ed., Vol. 2A, Wiley, New York, 1981, pp. 2491 2565.

41.S. Budavari (Ed.), Merck Index, 11th ed., Merck, Rahway, NJ, 1989, p. 1572 (No. 9899)

42.S. Budavari (Ed.), Merck Index, 11th ed., Merck, Rahway, NJ, 1989, p. 1247 (No. 7870).

1624 |

Asher Kalir and Henry H. Kalir |

43.T. I. Zarembinski and A. Theologis, Plant-Mol. Biol., 26, 1579 (1994).

44.T. Sato and A. Theologis, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 86, 8821 (1989).

45.E. M. Ward, J. M. Fajen, A. M. Ruder, R. A. Rinsky, W. E. Halperin and C. A. Fessler-Flesch,

Environ. Health Perspect., 103, 598 (1995).

46.R. L. Melnick and M. C. Kohn, Carcinogenesis, 16, 157 (1995).

47.A. A. Elfarra, J. E. Sharer and R. J. Duescher, Chem. Res. Toxicol., 8, 68 (1995).

48.J. E. Cochrane and T. R. Skopek, Carcinogenesis, 15, 713 (1994).

49.R. L. Melnick, R. C. Sillis, J. H. Boycroft, B. J. Chou, H. A. Ragan and R. A. Miller, Cancer Res., 54, 5333 (1994).

50.J. Kuzma, M. Nemecek-Marshall, W. H. Pollock and R. Fall, Curr. Microbiol., 30, 97 (1995).

51.C. J. Cavallito and J. H. Bailey, J. Am. Chem. Soc., 66, 1950 (1944).

52.F. Sandberg, Acta Physiol. Scand., 24, 7 (1951).

53.S. Budavari (Ed.), Merck Index, 11th ed., Merck, Rahway, NJ, 1989, p. 50 (No. 294).

54.S. Budavari (Ed.), Merck Index, 11th ed., Merck, Rahway, NJ, 1989, p. 574 (No. 3607).

55. L. Kangas, A. L. Nieminen, G. Blanco, M. Gronroos, S. Kallio, A. Karjalainen, M. Perila,

M. Dodervall and R. Toiwola, Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol., 17, 103 (1986).

56.G. W. Newell, A. K. Petretti and L. Rainer, J. Invest. Dermatol., 13, 145 (1949).

57.M. Beroza, M. N. Inscol, P. H. Schwartz, M. L. Keplinger and C. W. Mastri, Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol., 31, 421 (1975).

58.D. A. Carlson, M. S. Mayer, D. L. Silhacek, J. D. James, M. Beroza and B. A. Bierl, Science, 174, 76 (1971).

59. S. Budavari |

(Ed.), Merck Index, 11th ed., Merck, Rahway, NJ, 1989, pp. 1251 |

|

1252 |

|

|

||||

(Nos. 7891 |

|

7894). |

|

|

|

|

|

||

60.A. M. Nadzan, Annu. Rep. Med. Chem., 30, 119 (1995).

61.M. B. Sporn, A. B. Roberts and D. S. Goodman (Eds.), The Retinoids: Biology, Chemistry and Medicine, 2nd ed., Raven Press, New York, 1994.

62.H. Okuyama, N. Okajima, S. Sasaki, S. Higashi and N. Murata, Biochim. Biophys. Acta, 1084, 13 (1991).

63.S. P. Verma and A. Rastogi, Radiation Res., 122, 130 (1990).

64.M. N. Mruzek, in The Chemistry of Double-bonded Functional Groups: Supplement A2 (Ed. S. Patai), Wiley, Chichester, 1989, pp. 53 79.

65.L. Fay and R. Urs, J. Chromatogr., 541, 89 (1991); Chem. Abstr., 115, 11240 (1991).

66.K. H. Ney, Gordian, 88, 46 (1988); Chem. Abstr., 110, 23259 (1989)

67.F. Kong, Chin. Chem. Lett., 1, 109 (1990); Chem. Abstr., 115, 251551 (1991).

68.K. Yamamoto, A. Shibahara. T. Nakayama and G. Kajimoto, Yukagaku, 40, 497 (1991); Chem. Abstr., 115, 52205 (1991).