- •Lecture 1

- •5.2. Message Modulation

- •5.2.1. From m to m: Message Modulation

- •5. Dynamic Processes

- •5.2. Message Modulation 5.2.2. Modulated Messages (m')

- •5. Dynamic Processes 5.3. Discourse Interpreting

- •5. Dynamic Processes 5.3. Discourse Interpreting

- •Interpretation of ‘Discourse’ from Linguistic Perspective

- •Interpretation of ‘Discourse’ from Anthropological Linguistic Perspective

- •Interpretation of ‘Discourse’ from Systemic Functional Linguistic Perspective

Lecture 1

Discourse: Pragmatics and Interactional analysis in discourse

DEFINITION OF DISCOURSE. The difference between text and discourse

Originally the word 'discourse' comes from Latin 'discursus' which denoted 'conversation, speech'. Discourse is a term used in LINGUISTICS to refer to a continuous stretch of (especially spoken) LANGUAGE larger than a SENTENCE — but, within this broad notion, several different applications may be found. At its most general, a discourse is a behavioural UNIT which has a pre-theoretical status in linguistics: it is a set of UTTERANCES which constitute any recognisable SPEECH event, e.g. a conversation, a joke, a sermon, an interview… [Crystal, Dictionary of linguistics and phonetics, 3rd edn 1991]

In the broad sense discourse ‘includes’ TEXT (q.v.), but the two terms are not always easily distinguished, and are often used synonymously.

Some linguists would restrict discourse to spoken communication, and reserve text for written:

Text

1. result of the process of speech production in graphic form

2. indirect (processed) speech

3. no personal contacts between agents

4. perception of speech in different space and time

5. one agent

Discourse

1. The process of speech production in the form of a sound

2. Spontaneous speech in a particular situation with the help of verbal and nonverbal means

3. Personal contacts between agents

4. generation and perception of speech in a unity of space and time

5. two authors constantly change their roles ‘speaker – hearer’ (bilateral discourse).

There are a number of approaches to discourse analysis and pragmatics is one of them.

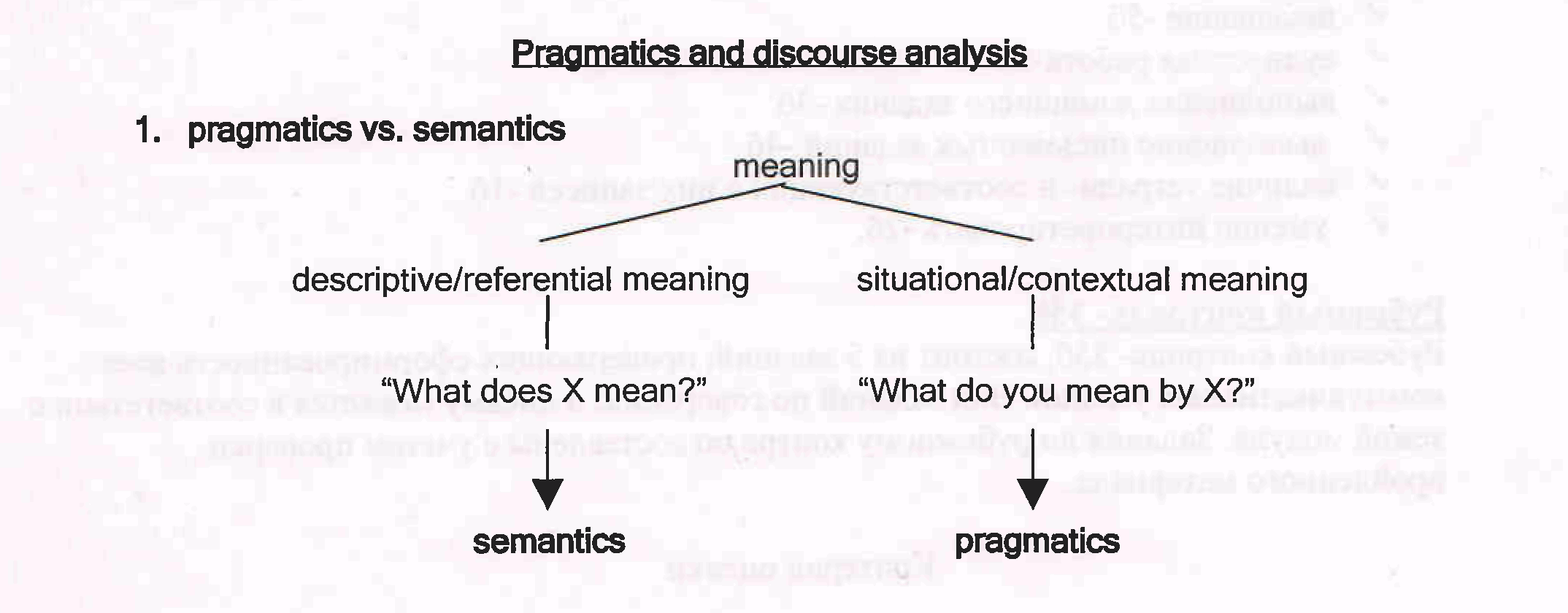

Definitions of pragmatics:

The underlying concepts behind pragmatics are meaning, context and communication. Early researchers considered pragmatics as having originated from semiosis, a process that involves the use of signs; hence signs are central to pragmatics users. Pragmatics is a broad approach to discourse that deals with the widely vast concepts of meaning, context and communication. Due to the wide scope of pragmatics, experts have failed to reach an agreement on the best definition of this approach. In language, pragmatics and discourse are closely connected. Discourse is the method, either written or verbal, by which an idea is communicated in an orderly, understandable fashion. Used as a verb, discourse refers to the exchange of ideas or information through conversation. Comparatively, pragmatics involve the use of language to meet specific needs or for a predetermined purpose. As such, pragmatics and discourse are related in that pragmatics are the means by which the purpose of discourse is achieved.

Both pragmatics and discourse involve concepts far deeper than mere word definitions and sentence structure. Unlike grammar, which involves the rules governing proper language structure, pragmatics and discourse focus on the meaningfulness of spoken or written language. Whether storytelling, explaining, instructing, or requesting, a speaker or writer has an intended purpose for communicating. How a speaker or writer constructs sentences to meet his intended

purpose involves both pragmatics and discourse.

It is only with the aid of considerations of a pragmatic nature that we can go beyond the question "What does this utterance mean?" and ask "Why was this utterance produced?".and explain how utterances are interpreted and how successful interpretation of utterances is managed. F.E.

1 Ms: (You should hurry up a little in persuading the PSOE, because we're all in a

hurry to do all that)

Mr: (Do you read the papers ?)

To know why Mr (Maragall) asks the question, we need to bear in mind quite a number of considerations of a pragmatic nature, for example, the degree of relevance of the question: in fact considerable, given that this is a political debate.

While discourse analysis can only explain that this is a reply to the observation made by Ms (Mas) or explain what type of sentences make up each of the utterances, pragmatics will explain what kind of reply it is, based on one or more implicatures. For example, "if you read the newspapers you will know that I have done so many times", or "as I am sure that you read the newspapers, I think you know perfectly well that I have done so, therefore your observation is unnecessary". Taking a pragmatic approach, the linguist can successfully

uncover the intention that Mr has in selecting "Do you read the papers?", and why he selected this utterance rather than another one.

Pragmatics' object of study is "language use and language users" (Haberland & Mey 2002, 1673).

Argumentative discourse. The concept of argument has a long history in communication. An argument is a concluding statement that claims legitimacy on the basis of reason. But argumentative discourse is a form of interaction in which the individuals maintain incompatible positions. More specifically, argumentative discourse directs attention to the arguments of naïve social actors engaged in intersubjective social interaction rather than the nature and structure of abstract arguments ( Willard 1989 ). The traditional notion of argument has the logical syllogism as its elemental structure. Thus, the concluding statement (A = C) is logically necessitated in: A = B, B = C, therefore A = C. A politician who states that “Democrats are liberals; my opponent is a democrat; therefore, my opponent is a liberal” is arguing from such syllogistic logic. Argument in this case is abstract and separate from the perspective of social actors.

Institutional discourse. Over the past thirty years or so, scholars of language and social life have investigated discourse within a variety of institutional contexts, most notably within schools, courtrooms, corporations, clinics and hospitals. In Institutional Discourse, you will have multiple opportunities to build on your knowledge and practice of discourse analysis by exploring some of the intriguing regions in which institutions and discourse intersect.

Lecture 2. Cognition in discourse (1 hour)

1) Portraying cognitive process

2) Cognitive process as an interactional event

3) Grasping the meaning of referents

- Tracking the ownership of knowledge

4) Discussion: informational terrain and cognitive process in conversation

Cognition is the word we use to refer to mental activities such as seeing, attending, remembering and solving problems. The study of cognition is the study of the cognitive processes that receive, transmit and operate upon information. These processes operate at every waking moment and they are also part of our personality, our intelligence and the way we interact socially. Comprehending them is, to a large extent, understanding what it means to be human. Their biological site is in the brain and, in psychiatry and neuroscience they are sometimes considered as mind-related.

Cognitive linguistics has emerged in the last twenty-five years as a powerful approach to the study of language, conceptual systems, human cognition, and general meaning construction.

It addresses within language the structuring of basic conceptual categories such as space and time, scenes and events, entities and processes, motion and location, force and causation. It addresses the structuring of ideational and affective categories attributed to cognitive agents, such as attention and perspective, volition and intention.

Cognitive linguistics recognizes that the study of language is the study of language use and that when we engage in any language activity, we draw unconsciously on vast cognitive and cultural resources, call up models and frames, set up multiple connections, coordinate large arrays of information, and engage in creative mappings, transfers, and elaborations. Language does not "represent" meaning; it prompts for the construction of meaning in particular contexts with particular cultural models and cognitive resources.

Cognitive linguistics goes beyond the visible structure of language and investigates the considerably more complex backstage operations of cognition that create grammar, conceptualization, discourse, and thought itself. The theoretical insights of cognitive linguistics are based on extensive empirical observation in multiple contexts, and on experimental work in psychology and neuroscience.

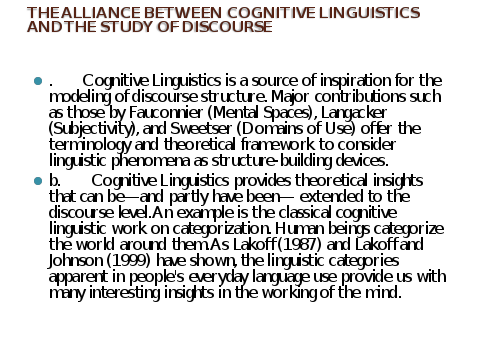

The alliance between Cognitive Linguistics and the study of discourse has become stronger in the recent past. This is a natural development. On the one hand, Cognitive Linguistics focuses on language as an instrument for organizing, processing, and conveying information; on the other, language users communicate through discourse rather than through isolated sentences.

a. Cognitive Linguistics is a source of inspiration for the modeling of discourse structure. Major contributions such as those by Fauconnier (Mental Spaces), Langacker (Subjectivity), and Sweetser (Domains of Use) offer the terminology and theoretical framework to consider linguistic phenomena as structure-building devices.

b. Cognitive Linguistics provides theoretical insights that can be—and partly have been— extended to the discourse level. An example is the classical cognitive linguistic work on categorization. Human beings categorize the world around them. As Lakoff (1987) and Lakoff and Johnson (1999) have shown, the linguistic categories apparent in people's everyday language use provide us with many interesting insights in the working of the mind. Over the last decade, the categorization of coherence relations and the linguistic devices expressing them have played a major role in text-linguistic and cognitive linguistic approaches to discourse. For instance, the way in which speakers categorize related events by expressing them with one connective (because) rather than another (since) can be treated as an act of categorization that reveals language users' ways of thinking.

c. Cognitive Linguistics is the study of language in use; it seeks to develop so-called usage-based models (Barlow and Kemmer 2000) and in doing so increasingly relies on corpora of naturally occurring discourse that make it possible to adduce cognitively plausible theories to empirical testing.

d. Cognitive Linguistics typically appreciates the methodological strategy of converging evidence. In principle, linguistic analyses are to be corroborated by evidence from areas other than linguistics, such as psychological (Gibbs 1996) and neurological processing studies.

We have discourse analysis, and its many branches (stylistics, rhetoric, narrative or argumentation analysis, as well as syntactic, semantic or pragmatic analysis, and of course conversation analysis), but "cognitive analysis" is not a well-known, standard way of looking at text or talk.

We have a cognitive psychology of discourse processing (production, comprehension), and we have a social psychology of discourse (the Loughborough school) called "discursive psychology", but the latter rejects any mental approach and in fact advocates a more ethnomethodological approach to discourse within social psychology.

A psychological or cognitive study of discourse is rather different from a more formal, grammatical or (say) stylistic, narrative or argumentative analysis. It does not deal with abstract categories and rules purported to describe 'structures' of discourse, but with the actual mental representations and processes of language users. In that respect, psychology intends to provide a more 'empirically' based understanding of discourse.

in a cognitive analysis, interpretation is not static, nor an abstract procedure, as in linguistic semantics, but a dynamic, ongoing process of (at first tentatively) assigning meaning and functions to units of discourse.

In order to account for such processes of production and understanding, psychology makes use of a large number of more or less technical notions describing various aspects of the 'mind':

Short Term Memory (STM) vs. Long Term Memory (LTM)

Episodic Memory vs. Semantic Memory

Situation or Even Models

Knowledge (scripts, etc.)

A cognitive analysis as intended does not at all exclude a further social analysis. Indeed, many aspects of cognitive representations and processing are themselves social -- such as the socially shared knowledge and other beliefs, as well as the jointly constructed social aspects of the context. Indeed, discourse processing and understanding is studied at all levels as part of a communicative event, as a form of social interaction, for which in fact it provides a further cognitive basis: also action and interaction derives its meanings, functions and coordination from cognitive representations that ongoingly monitor it.

"Cognitive analysis" of discourse, however, is NOT the same as a psychological study of discourse processing. Psychology focuses on the structures and processes of mental representations, and does so, for instance, with experiments, or using other forms of evidence of what actually goed on in the mind. So, cognitive analysis is not going to measure reading or reaction times, or any other method psychologists use to test their hypotheses.

Cognitive analysis is focused on discourse and its structures, but derives its terms from the theory of discourse processing.

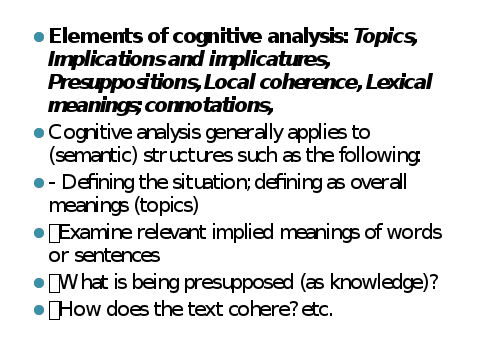

Elements of cognitive analysis: Topics, Implications and implicatures, Presuppositions, Local coherence, Lexical meanings; connotations, We have only given a short list of examples for cognitive analysis. However, we see that a cognitive analysis generally applies to (semantic) structures such as the following:

- Defining the situation; defining as overall meanings (topics)

Examine relevant implied meanings of words or sentences

What is being presupposed (as knowledge)?

How does the text cohere? etc.

Most of these semantic structures, as well as many others, can only be accounted for in terms of personal or socially shared knowledge, and require listing relevant knowledge or other beliefs.

Lecture 3

An overview of socio-cultural theory in discourse

Discourse analysis is one of the principal methodologies of sociocultural research in education. sociocultural research focuses on understanding how cognitive, social, cultural, affective, and communicative factors influence instruction. we review how sociocultural theory conceptualizes teaching and learning, some fundamental constructs of both the theory and the methodology, and the basic guidelines for discourse analysis. we discuss the applications of sociocultural theory and discourse analysis to remedial and special education by focusing on three areas of research: the social construction of disability, contingent instruction between adults and learners, and miscommunication between adults and working class or minority students.

An emerging body of work in social, political and educational fields is interested in integrating ethnographic and discourse analytical approaches. This field includes a wide range of studies,

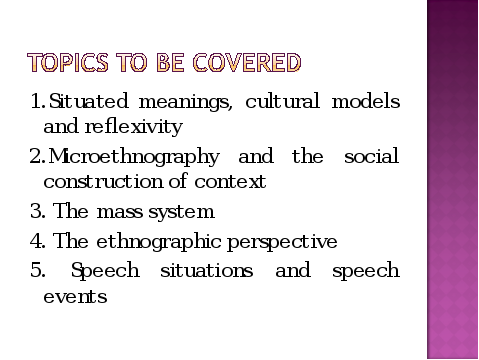

2.1 Ethnographic perspectives

Ethnography is concerned with understanding and describing meaning in social life. Ideally, it involves sustained involvement in a research site through fieldwork, and the recording of social activity in as much of its complexity and messiness as possible. As such, ethnography is at once a research methodology, a set of fieldwork techniques, most prominently participant observation, and a research product, a reflexive account of social life that prioritizes participants' perspectives. As a theoretical and methodological perspective on situated practices, ethnography is particularly useful for examining discourse production.

We begin the discussion of discourse and language by introducing two types of meaning that attach to words and phrases in actual use: situated meanings and cultural models. After a brief discussion of these two notions, we turn to a discussion of an important and related property of language-in-use, a property ethnomethodologists call refiexivity. Through these constructs, we examine language as social action with a focus on what members of a social group are accomplishing through their discourse, rather than focusing solely on language form or function.

Situated Meanings and Cultural Models

A situated meaning is an image or pattern that we (participants in an interaction) assemble "on the spot" as we communicate in a given context, based on our construal of that context and on our past experiences. For example, consider the following two utterances: "The coffee spilled, get a mop" and "The coffee spilled, get a broom." In the first case, triggered by the word mop (a lexical cue), a hearer (or reader) may assemble the situated meaning as something like "dark liquid we drink" for "coffee," by using his or her experience in similar situations. In the second case, triggered by the word broom and personal experience in such matters, a hearer (or reader) may assemble a situated meaning as something like "grains that we make our coffee from" or "beans from which we grind coffee."

These contrasting cases provide a point of departure for the discussion of situated meaning. However, in a real context, there are many more signals as to how to go about assembling situated meanings for words and phrases. Gumperz (1982a) called such cues (or clues) contextualization cues. They include prosodic and nonverbal cues such as pitch, stress, intonation, pause, juncture, proxemics (distance between speakers, spatial organization of speakers), eye gaze, and kinesics (gesture, body movement, and physical activity), in addition to lexical items, grammatical structures, and visual dimensions of context. Such cues provide information to participants about the meaning of words and grammar and how to move back and forth between language and context (situations).

Words are also associated with "cultural models." Cultural models are "story lines," families of connected images (like a mental movie), or (informal) "theories" shared by people belonging to specific social or cultural groups (Cole, 1996; D'Andrade & Strauss, 1992; Geertz, 1983; Holland &. Quinn, 1987; Spradley, 1980). Cultural models "explain,11 relative to the standards (norms) of a particular social group, why words have the range of situated meanings they do for members and shape members' ability to construct new ones. They also serve as resources that members of a group can use to guide their actions and interpretations in new situations.

Cultural models are usually not stored in any one person's head but are distributed across the different sorts of "expertise" and viewpoints found in a group (Hutchins, 1995; Shore, 1996), much like a plot of a group-constructed (oral or written) story in which different people have different bits of information, expertise, and interpretations that they use to contribute to the plot being negotiated. Through this process of joint construction of text, then, members construct local meanings that they draw on to mutually develop a "big picture."

From this theoretical position, not all of the bits and pieces of cultural models or principles of practice are consciously in people's heads, and different bits and pieces are shared across different people and groups. Through interactions, members appropriate the bits and pieces available to them within a social group, and these bits and pieces often become part of people's taken-for-granted social practices. In this way, members construct—and, at times, reconstruct— cultural models socially significant to appropriate participation within their social group. This view of the situated nature of meaning and the constructed nature of cultural knowledge places particular demands on discourse analysts. The task of the discourse analyst is to construct representations of cultural models by studying people's actions across time and events. In closely observing the concerted actions among members, examining how and what members communicate, and interviewing members (see Briggs, 1986, and Mishler, 1986, for discussions of the constructed nature of interviews), the analyst asks questions about the patterns of practice that make visible what members need to know, produce, and interpret to participate in socially appropriate ways (Heath, 1982).

One way to approach the study of cultural models is through the use of an ethnographic perspective to guide a discourse analysis. While this approach is not the same as doing ethnography, Green and Bloome (1983,1997) argue that the cultural perspective guiding ethnography can be productively used in discourse studies (hence the term ethnogaphic perspective). One way to assess how discourse and ethnographic perspectives are conceptually related is through the definition of the phenomenon of study in ethnography by Spindler and Spindler (1987):

Within any social setting, and any social scene within a setting, whether great or small, social actors are carrying on a culturally constructed dialogue. This dialogue is expressed in behavior, words, symbols, and in the application of cultural knowledge to make instrumental activities and social situations work for one. We learn the dialogue as children, and continue learning it all of our lives, as our circumstances change. This is the phenomenon we study as ethnographers—the dialogue of action and interaction, (p. 2)

In summarizing the goals and purpose of ethnography in this way, they place the study of "dialogue" in the center of the work, whether that dialogue be through discourse or through action. Discourse analysis, then, when guided by an ethnographic perspective, forms a basis for identifying what members of a social group (e.g., a classroom or other educational setting) need to know, produce, predict, interpret, and evaluate in a given setting or social group to participate appropriately (Heath, 1982) and, through that participation, learn (i.e., acquire and construct the cultural knowledge of the group). Thus, an ethnographic perspective provides a conceptual approach for analyzing discourse data (oral or written) from an (insider's) perspective and for examining how discourse shapes both what is available to be learned and what is, in fact, learned.8

Lecture 4

Discourse Interpreting

After these remarks on what the process of translation is, I intend, from now on, to focus this discussion on translation as a communication activity and not as a mere product, involving the negotiation of meanings between producers and receivers of a text. In this sense, the discussion on translation activities goes far beyond the linguistic aspects underlying a text but it regards the social, cultural and psychological dimensions of the process. Thus, the translation activity should be studied as a discursive practice, where different reflexive actions are performed, such as: reading, interpreting, analysis, making decisions and others, which surpass the level of words and sentences reaching the level of discourse.

According to Fairclough (1992), discourse is the relationship between text and social practice. He conceptualizes discourse in three important dimensions: text, discursive practice and social practice (Figure 2). Shortly, we could say that the text is the discursive event, the central part of the discourse which deals with the linguistic aspects of the language; the discursive practice is related to the text production, distribution and consumption of the text and involves the analysis of the text as discourse - the interpretation of ideas which brings about the social function of a text; and finally, the social practice establishes the relationship between discourse and the social structure as a whole - how the discourse articulated by the text may affect current society, by changing values, behavior, concepts, etc.