Chapter 1

.pdf

C H A P T E R

An Overview of Finance

Chapter Objectives

This is a unique finance textbook. Introductory finance texts are usually titled Financial Management or Intro-

duction to Corporate Finance and they focus exclusively on finance applied to business or corporate problem solving and decision making. However, finance is much broader in scope than these texts suggest. Finance also includes

By the end of this chapter you should be able to:

1.Define the major areas of study within the finance discipline

2.Identify the topics and some of the key concepts that will be studied in this course

3.Understand the scope of the financial system and the individual's role in it

4.Discuss the financial manager's role within a corporation

5.Describe the foundation assumptions that underlie the study of finance

the study of investments and financial markets. The study of investments includes learning how to convert current dollars into a greater amount of future dollars. The study of financial markets includes learning how the interaction among the various players establishes security prices and facilitates security trading. Finance majors will take separate courses in each of these topic areas, but the course you are taking now provides a foundation in all of them. If this is the only course in finance you take, it will provide a sufficient background to enable you to read and understand popular financial literature. It will also provide a framework for how you should think about financial issues and prepare you for more advanced topics, should you choose to pursue the study of finance further.

This chapter briefly discusses the three major areas of study within the finance discipline. It then introduces the financial system and explains how we will approach the study of each element. Finally, the chapter discusses some fundamental assumptions that will be carried throughout the book.

This may be the most important course you will take during your college career. You will learn how to manage money on both the corporate

CHAPTER 1 An Overview of Finance |

3 |

and personal levels. You will learn to read business periodicals and understand investment advisors. You will learn the correct approach to solving business and personal investment problems. These lessons may have a tremendous impact on your career in business as well as on your personal wealth and security. For example, if you go to work for a firm after graduation, you will probably start your first day in the personnel office. There, you may be asked to choose how your retirement dollars are to be invested. You will learn in this course that one selection may leave you without enough funds to retire when you desire, but another, if history repeats itself, may let you retire early. In this course you will learn how to evaluate retirement options, select among auto and home loans, and analyze business opportunities. You will learn how to evaluate a firm's health and how to project its future.

WHAT IS FINANCE?

Broadly defined, finance is the study of managing money. At the most basic level this involves determining where to get money and what to do with it. Clearly, finance is central to a wide variety of jobs, disciplines, and activities. Bankers, accountants, financial planners, and many others make their living using financial concepts on a daily basis. Still others use the concepts less directly, but benefit from an understanding of the basics. It is difficult to think of any job that does not require at least some understanding of financial principles. Even an artist must price art fairly and deal with estimating cash flows. Additionally, everyone should take responsibility for his or her own retirement security and plan for it accordingly, which requires an understanding of finance.

It will become obvious as you read this book that many of the distinctions between the fields of study in finance are artificial. For example, the study of how interest rates are determined is normally considered part of markets and institutions. However, corporate managers and investors are keenly interested in interest rates and follow them closely. Similarly, both business managers and investors are concerned with how securities are priced. This text points out diverse applications as each topic is presented to help you achieve an integrated picture of the entire field of finance.

Markets and Institutions

A student majoring in finance will take at least one course in financial markets. The study of financial markets includes the determination of interest rates and how the market prices and distributes securities. To simplify the study of financial markets in Chapter 2, our discussion will be based on the maturity of the securities that trade there. Money markets are for securities that mature in less than 1 year. Capital markets are for securities that mature in more than 1 year. We will also investigate how financial markets facilitate trading and increase the accuracy of security pricing.

The study of financial institutions includes learning how banks, thrifts, the Federal Reserve, and finance companies increase the efficiency of financial transactions. Everyone interacts with financial institutions. Business managers deal with investment bankers who help take securities public. Individuals deal with banks for loans and with

4 |

PART I Markets and Institutions |

|

other investment institutions to invest for retirement. You will save money and time if |

|

you understand which institution specializes in each type of service you need. Addi- |

|

tionally by understanding the motives and constraints facing the various institutions, |

|

you are more likely to successfully obtain the services you seek. We begin our study of |

|

financial institutions in Chapter 3. |

|

Another important topic covered in markets and institutions courses is the deter- |

|

mination of interest rates. It is often important to both individuals and business man- |

|

agers to understand the factors that influence interest rates so that they can make |

|

educated predictions about future interest rates. For example, in 1992 long-term mort- |

|

gage interest rates fell from about 10% to less than 8%. Many homeowners were faced |

|

with the question of whether they should refinance their home loans immediately or wait |

|

for rates to drop further. It turned out that long-term rates increased for two years before |

|

falling back to the level achieved in 1992. Homeowners who waited for rates to fall lost |

|

several years of lower payments. An understanding of interest rates can lead to better |

|

financial decision making. We will investigate how interest rates are determined and the |

|

factors that influence them in Chapter 4. |

|

We extend our study of interest rates to the Federal Reserve, which is the central |

|

bank of the United States. Besides being the government's bank and the bank for banks, |

|

it also has tremendous control over the economy and interest rates. Because of the Fed- |

|

eral Reserve's critical influence over both investors and businesses, we will study it sep- |

|

arately from the other financial institutions in Chapter 5. |

Investments

The second major concentration within finance is investments. The study of investments is the study of how dollars available today can be turned into more dollars in the future. At one time, most individuals had few investment choices. It was difficult to buy stocks with only moderate wealth, and corporate pension plans offered few options to employees. The investment landscape is very different today. As we will discuss later, investors build portfolios of securities. A portfolio is simply a group of different investments. Wise investors hold a variety of securities in their portfolios to reduce their risk, an investment strategy called diversification. Mutual funds enable investors with limited funds to buy a diversified portfolio of securities. Most corporations now give employees a number of investment alternatives. A thorough grounding in investments will help you to understand the implications of these alternatives and to select the best ones for yourself.

We begin our study of investments in Chapter 6 by learning how money grows when invested over time and how future dollars are worth less than dollars we have now. You will learn to solve many real-world problems in this chapter.

One of the most important topics in finance is the risk-return tradeoff. To get greater returns, you must be willing to incur greater risk. Although this concept seems straightforward, it gets more complex when we try to precisely define risk and to determine exactly how it affects returns. We will study the risk-return relationship in Chapter 7.

Anyone buying or investing in securities needs to know how the market arrives at a price. It is easy to find the value of bonds, but we will discover that it is much more

CHAPTER 1 An Overview of Finance |

5 |

difficult to accurately price stock. Like risk and return, asset valuation is important both to businesses selling securities and to investors buying them for their portfolios. We address asset valuation and explain how well our valuation theories work in practice as we discuss security pricing in Chapters 8 and 9. The discussion of market efficiency at the end of Chapter 9 ties our study of markets to our study of market pricing.

Corporate Finance

Corporate finance is finance applied in a business setting. This is the typical focus of introductory finance courses. We will cover most of the topics included in traditional corporate finance texts; however, we will include a personal investment slant whenever possible. Most of you will work for a corporation at some time in your future. You may even run your own firm. For this reason, even if you are never employed as a financial manager, you will benefit from the lessons taught here. Within the study of corporate finance, there are several subareas of study.

Evaluation of Long-Term Projects

The financial manager is responsible for evaluating whether a firm should pursue a particular investment opportunity. For example, Ford Motor Co. recently decided to make a multi-million dollar investment in engineering and production to produce right-hand drive vehicles for sale in Japan. The financial managers of Ford had to determine whether they could realistically expect to recoup this investment or whether Ford could use its resources better elsewhere. We will examine the most commonly used methods for project evaluation in Chapters 10 and 11.

Study of How to Acquire Funds

One of the most important yet difficult decisions facing the financial manager is how to fund the firm's investments. Consider the problems faced by many of the new dot com companies, such as Amazon.com. During its early years it focused on gaining market share as opposed to generating profits. Amazon's management decided that its long-run success depended more on building a customer base than on generating revenues. Many Web retailing firms believed this model. It is much like how the focus is on acquiring property at the beginning of a game of Monopoly. The winner will be the one with the most property, not the one with the most cash on hand.

The dot com companies had to find ways to support their growth until revenues increased sufficiently to generate profits. There are three options facing the firm: borrow a huge amount of money, sell stock to the public, or sell the entire firm to a larger corporation that has the resources to fund the expansion. The decision managers make will affect the very survival of the firm. We will look at how a decision such as this may be tackled in Chapters 12 and 13.

Analyzing Firm Performance

In Chapter 14 we analyze firms using ratios and common-size financial statements. Ratios help the financial manager to identify areas needing attention. Ratio analysis can help the financial manager identify the strengths and weaknesses of a firm. Chapter 15

6 PART I Markets and Institutions

extends the concepts learned in Chapter 14 by using ratios to forecast a company's future strengths and weaknesses.

We conclude our study of corporate finance by reviewing the management of short-term capital, which is how to correctly use current assets and current liabilities, in Chapter 16.

Chapters 17 and 18 conclude the text and integrate the various areas of finance by taking a look at how well the ideas and theories advanced earlier in the book can be used to solve real-life problems. In Chapter 17 we extend our discussion to international markets. In Chapter 18 we follow an entrepreneur through her life as she uses the financial lessons taught in this course to solve a variety of different business and personal finance problems.

To help link the various topic areas together into a cohesive unit we next introduce the financial system.

Self-Test Review Questions*

Answers to Self-Test Review Questions appear at the bottom of the page on which the question is located.

1.How is finance defined?

2.What are the three main areas of finance?

FINANCIAL SYSTEM

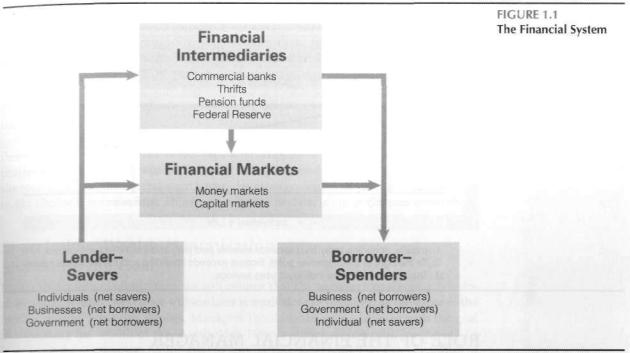

The earlier discussion might have led you to conclude, incorrectly, that the field of finance is segregated into distinct areas of study. In fact, all of the topics discussed in the last section fit together in the financial system,which is shown graphically in Figure 1.1. On the far left we see that three groups provide funds: individuals, businesses, and the government.

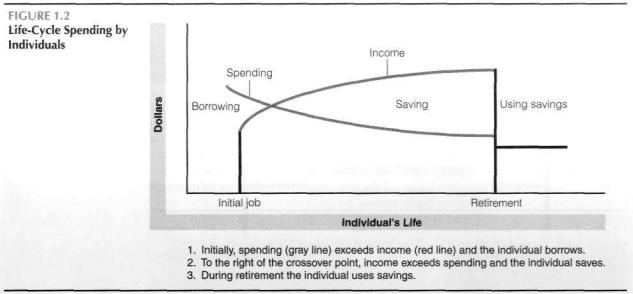

Individuals are the primary investors in the economy. Ultimately, they own every business asset. Individuals invest their savings in the financial system with the expectation of converting them into greater savings for the future. Figure 1.2 shows the typical life-cycle spending by individuals or households. During his or her early years, a person may spend more than is earned. For example, you may be borrowing money to pay for your education. Eventually, you hope to go to work and to earn enough to pay back these loans and begin building up a nest egg (a reserve sufficient to cover emergencies and retirement). You will use this nest egg when you retire and your income falls below your level of spending.

The financial system plays a critical role in the individual's financial life cycle. Initially, the markets and intermediaries provide a source of funds when you need to borrow. For instance, you will become acquainted with the mortgage market when you buy your first house. You may have already participated in the money markets if you have borrowed money to buy a car. Undoubtedly you have already dealt with banks, which are financial intermediaries.

Later in life, when your income rises, you will begin investing. This may be through an intermediary known as a pension fund, or it may be through banks and stock bro-

CHAPTER 1 An Overview of Finance |

7 |

kerage houses. However you choose to invest, the markets, with the aid of intermediaries, will channel your savings to borrower-spenders. Borrower-spenders are listed on the right side of Figure 1.1. They include businesses, the government, and individuals. These borrower-spenders pay for the right to use your money for a period of time.

The financial system relies on all of its parts to function. Without you, the individual, there would be no money available for those who need to borrow it. Without the markets and the intermediaries, investors would have difficulty channeling funds to borrowers. Without the borrower-spender, investors would have nowhere to invest.

Note from Figure 1.1 that individuals, businesses, and the government are each sometimes lenders and sometimes borrowers. Businesses and the government often have temporary surplus funds to lend. Across the whole economy, however, businesses and the government borrow, which is why they are listed first in the Borrower-Spenders box. Similarly, individuals at times are borrowers. However, in aggregate, individuals are the source of investment funds and so are listed first in the Lender-Savers box.

Keep this diagram of the financial system in mind as we move through the text. In Part One we investigate the markets, intermediaries, and interest rates. In Part Two we look at investments, including how cash flows are adjusted for time, how risk and return are related, how assets are valued, and how we may evaluate a firm before making an investment. In Part Three we move our focus to the business. We study how businesses choose between using debt or equity to fund growth and how they choose between investment opportunities, plan for the future, and manage short-term assets.

Before we launch into our study of financial markets and institutions in Chapter 2, let us first establish what financial managers are attempting to accomplish.

8 |

PART I Markets and Institutions |

ROLE OF THE FINANCIAL MANAGER

A firm's accountants report the recent history of the firm's earnings (the income statement) and provide a snapshot of the current fiscal condition of the firm (the balance sheet). As important as these functions are, no company succeeds by looking back. The financial manager is responsible for making decisions that affect the future of the firm. The financial manager evaluates future investments, projects, product introductions, and financing. On the basis of this analysis, the firm makes decisions that affect its very survival. It is helpful to have a single goal in mind when making financial decisions. This goal enables us to establish methods to make choices that will ensure profitability.

Maximizing Profit Is Not Enough

A rational goal to consider would be for managers to maximize the firm's profits. A manager who is maximizing profits makes decisions that result in the highest profits to the firm in every period. Is this really what we want our managers to do?

Consider the case of Fresh International, a privately held firm now run by the grandson of the founder. The California-based firm grows vegetables and sells them as salad. In the early 1980s the firm began developing a method to preserve salad in a bag. Initial efforts were a dismal failure (buyers found themselves with a bag of ugly brown mush). Clearly, the early efforts were a cost that the firm could have saved. They took money, time, and energy away from the firm's main business: growing and marketing lettuce. Finally, in 1989 Fresh International's scientists developed a special bag that lets out carbon dioxide without letting in oxygen. The result was bagged salad that would last on retailers' shelves. Total

CHAPTER 1 An Overview of Finance |

9 |

sales for Fresh International in 1995 were about $450 million, with about $350 million from the sale of bagged salads. Postponing current period profits for future sales seems to have paid off. This example suggests one problem with the profit maximization goal: Profit maximization can result in short-sighted management decisions.

Another problem with the profit maximization goal is that it ignores risk. A manager whose goal is to maximize profits, if faced with two investment options, would choose the one with the highest expected profit, despite its having much higher risk than the alternative.

Finally, the timing of the cash flows is important. In general it is better to get cash flows to the company sooner rather than later. Suppose a manager was evaluating two projects. One gave large payments initially and the second gave large payments later. If the total profits of the second were larger, the manager with a profit maximization goal might choose it over the first. This may not be the best decision, as Chapter 6 will show.

Shareholder Wealth Maximization

Should Be the Goal

Rather than profit maximization, we will assume that the manager's goal is to maximize shareholder wealth (which we will see later is equivalent to maximizing the value of the firm). Consider what this implies. Managers should make every decision with the goal of increasing the wealth of the shareholder. How is shareholder wealth increased? By increasing the stock price. So the goal of maximizing shareholder wealth is equivalent to the goal of maximizing stock price. Because investors buy stock for the sole purpose of making money, this goal will please them. Pleased shareholders will reelect directors, who will reward managers with higher salaries.

If the goal is to increase shareholder wealth, how can managers achieve this goal? Shareholder wealth is measured as the number of shares held multiplied by the price per share. For example, at the time of this writing William Gates, the CEO and largest shareholder of Microsoft, owns 741,749,300 shares of Microsoft stock. With Microsoft selling at $59,375 per share, Gates's wealth is $44.04 billion. To increase his wealth, Gates must increase the stock price.1 Thus, the wealth maximization goal puts the emphasis on increasing the stock price rather than on profits or earnings per share (EPS). In Chapter 9 we will examine determinants of stock price in more detail, but we can briefly review them here. If a firm's risk falls, investors will pay a higher price for the stock. Similarly, if the projected cash flows increase, the stock price will rise, and it will rise more quickly if investors expect the cash flows sooner rather than later.

The wealth maximization goal leads to a very rational directive to managers: Increase the firm's cash flows, get those cash flows to the firm as soon as possible, and do this while minimizing risk. This goal allows us to develop strategies for evaluating projects that provide clear answers to investment questions.

10 |

PART I Markets and Institutions |

Straying from the Wealth Maximization Goal

In practice, managers do not always adhere to the goal of maximizing shareholder wealth. Consider that Business Week2 reported that the cost of operating a private corporate jet averages nearly $10,000 per hour, including depreciation, pilot salaries, and insurance. Despite these high costs, many managers choose to buy a company plane rather than use commercial airlines. In these cases, managers may be looking out for their own welfare and comfort more aggressively than for the welfare of shareholders. This problem arises because managers, rather than owners, run many companies. Managers, as agents of owners, recognize that they will not benefit as much from increasing shareholder wealth as they may by running the company to suit their own agendas. For example, managers could have the company buy expensive luxury cars for their use. This does not increase the wealth of shareholders, but it may make the manager happy. An agency cost is any benefit a manager derives from a company that does not increase shareholder wealth and is not part of the manager's agreed-upon compensation. Agency costs include fancy offices, corporate jets, beachfront condos, and Friday afternoons off for golf. Less obvious costs of the agency relationship, but just as significant, are those associated with reducing agency costs. For example, hiring expensive accounting firms to monitor management decisions and provide accurate accounting and financial information is also an agency cost.

It is often difficult for shareholders to control agency costs. One reason is that the shares of stock in most large companies are so widely distributed that no one shareholder has the incentive or the power to discipline wayward managers. Many argue that the takeover market is one of the best sources of corporate discipline available. Managers who are looking out for their own interests over the interests of shareholders are likely to be replaced when the firm is taken over by another firm.

Boards of directors give many managers stock options and stock incentive plans to help align their interests with those of shareholders. One famous example of this was when Lee Iacocca became CEO of Chrysler. He received a salary of $1 per year plus stock options. At the time, Chrysler was near bankruptcy. By saving the company and increas-