- •ICU Protocols

- •Preface

- •Acknowledgments

- •Contents

- •Contributors

- •1: Airway Management

- •Suggested Reading

- •2: Acute Respiratory Failure

- •Suggested Reading

- •Suggested Reading

- •Website

- •4: Basic Mechanical Ventilation

- •Suggested Reading

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •7: Weaning

- •Suggested Reading

- •8: Massive Hemoptysis

- •Suggested Reading

- •9: Pulmonary Thromboembolism

- •Suggested Reading

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •11: Ventilator-Associated Pneumonia

- •Suggested Readings

- •12: Pleural Diseases

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •13: Sleep-Disordered Breathing

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •14: Oxygen Therapy

- •Suggested Reading

- •15: Pulse Oximetry and Capnography

- •Conclusion

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •16: Hemodynamic Monitoring

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •17: Echocardiography

- •Suggested Readings

- •Websites

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •19: Cardiorespiratory Arrest

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •20: Cardiogenic Shock

- •Suggested Reading

- •21: Acute Heart Failure

- •Suggested Reading

- •22: Cardiac Arrhythmias

- •Suggested Reading

- •Website

- •23: Acute Coronary Syndromes

- •Suggested Reading

- •Website

- •Suggested Reading

- •25: Aortic Dissection

- •Suggested Reading

- •26: Cerebrovascular Accident

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •27: Subarachnoid Hemorrhage

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •28: Status Epilepticus

- •Suggested Reading

- •29: Acute Flaccid Paralysis

- •Suggested Readings

- •30: Coma

- •Suggested Reading

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •32: Acute Febrile Encephalopathy

- •Suggested Reading

- •33: Sedation and Analgesia

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •34: Brain Death

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •35: Upper Gastrointestinal Bleeding

- •Suggested Reading

- •36: Lower Gastrointestinal Bleeding

- •Suggested Reading

- •37: Acute Diarrhea

- •Suggested Reading

- •38: Acute Abdominal Distension

- •Suggested Reading

- •39: Intra-abdominal Hypertension

- •Suggested Reading

- •Website

- •40: Acute Pancreatitis

- •Suggested Reading

- •Website

- •41: Acute Liver Failure

- •Suggested Reading

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •43: Nutrition Support

- •Suggested Reading

- •44: Acute Renal Failure

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •45: Renal Replacement Therapy

- •Suggested Reading

- •Website

- •46: Managing a Patient on Dialysis

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •47: Drug Dosing

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •48: General Measures of Infection Control

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •49: Antibiotic Stewardship

- •Suggested Reading

- •Website

- •50: Septic Shock

- •Suggested Reading

- •51: Severe Tropical Infections

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •52: New-Onset Fever

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •53: Fungal Infections

- •Suggested Reading

- •Suggested Reading

- •Website

- •55: Hyponatremia

- •Suggested Reading

- •56: Hypernatremia

- •Suggested Reading

- •57: Hypokalemia and Hyperkalemia

- •57.1 Hyperkalemia

- •Suggested Reading

- •Website

- •58: Arterial Blood Gases

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •59: Diabetic Emergencies

- •59.1 Hyperglycemic Emergencies

- •59.2 Hypoglycemia

- •Suggested Reading

- •60: Glycemic Control in the ICU

- •Suggested Reading

- •61: Transfusion Practices and Complications

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •Suggested Reading

- •Website

- •63: Onco-emergencies

- •63.1 Hypercalcemia

- •63.2 ECG Changes in Hypercalcemia

- •63.3 Superior Vena Cava Syndrome

- •63.4 Malignant Spinal Cord Compression

- •Suggested Reading

- •64: General Management of Trauma

- •Suggested Reading

- •65: Severe Head and Spinal Cord Injury

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •66: Torso Trauma

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •67: Burn Management

- •Suggested Reading

- •68: General Poisoning Management

- •Suggested Reading

- •69: Syndromic Approach to Poisoning

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •70: Drug Abuse

- •Suggested Reading

- •71: Snakebite

- •Suggested Reading

- •72: Heat Stroke and Hypothermia

- •72.1 Heat Stroke

- •72.2 Hypothermia

- •Suggested Reading

- •73: Jaundice in Pregnancy

- •Suggested Reading

- •Suggested Reading

- •75: Severe Preeclampsia

- •Suggested Reading

- •76: General Issues in Perioperative Care

- •Suggested Reading

- •Web Site

- •77.1 Cardiac Surgery

- •77.2 Thoracic Surgery

- •77.3 Neurosurgery

- •Suggested Reading

- •78: Initial Assessment and Resuscitation

- •Suggested Reading

- •79: Comprehensive ICU Care

- •Suggested Reading

- •Website

- •80: Quality Control

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •81: Ethical Principles in End-of-Life Care

- •Suggested Reading

- •82: ICU Organization and Training

- •Suggested Reading

- •Website

- •83: Transportation of Critically Ill Patients

- •83.1 Intrahospital Transport

- •83.2 Interhospital Transport

- •Suggested Reading

- •84: Scoring Systems

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •85: Mechanical Ventilation

- •Suggested Reading

- •86: Acute Severe Asthma

- •Suggested Reading

- •87: Status Epilepticus

- •Suggested Reading

- •88: Severe Sepsis and Septic Shock

- •Suggested Reading

- •89: Acute Intracranial Hypertension

- •Suggested Reading

- •90: Multiorgan Failure

- •90.1 Concurrent Management of Hepatic Dysfunction

- •Suggested Readings

- •91: Central Line Placement

- •Suggested Reading

- •92: Arterial Catheterization

- •Suggested Reading

- •93: Pulmonary Artery Catheterization

- •Suggested Reading

- •Website

- •Suggested Reading

- •95: Temporary Pacemaker Insertion

- •Suggested Reading

- •96: Percutaneous Tracheostomy

- •Suggested Reading

- •97: Thoracentesis

- •Suggested Reading

- •98: Chest Tube Placement

- •Suggested Reading

- •99: Pericardiocentesis

- •Suggested Reading

- •100: Lumbar Puncture

- •Suggested Reading

- •Website

- •101: Intra-aortic Balloon Pump

- •Suggested Reading

- •Appendices

- •Appendix A

- •Appendix B

- •Common ICU Formulae

- •Appendix C

- •Appendix D: Syllabus for ICU Training

- •Index

Quality Control |

80 |

|

|

Subhash Todi and Ashit Bhagwati |

|

Case 1

A 70-year-old male patient with dementia and Parkinson’s disease was admitted to the ICU with the confusional state. He fell from his bed on the night of admission and suffered scalp injuries. How would you ensure that similar accidents do not happen in the future?

Case 2

A 60-year-old male patient was admitted to hospital with hypertensive intracerebral bleed and required ventilatory support. On the fourth day of admission, he developed features of ventilator-associated pneumonia. What measures should have been in place to avoid this complication?

Case 3

A 30-year-old male patient was admitted to hospital with gastroenteritis and severe hypokalemia. He was inadvertently administered high concentration of potassium in intravenous infusion through the central line and suffered a cardiac arrest. How could you have prevented such errors?

In a landmark publication, To Err Is Human: Building a Safer Health System, a decade ago by the Institute of Medicine USA, it was described that human error was one of the common causes of morbidity, mortality, and increased health care cost in hospitalized patients worldwide. Experts estimate that as many as 98,000 people die

S. Todi, M.D., M.R.C.P. (*)

Critical Care & Emergency, A.M.R.I. Hospital, Kolkata, India e-mail: drsubhashtodi@gmail.com

A. Bhagwati, M.D.

Department of Internal Medicine and Critical Care, Bhatia Hospital, Mumbai, India

R. Chawla and S. Todi (eds.), ICU Protocols: A stepwise approach, |

649 |

DOI 10.1007/978-81-322-0535-7_80, © Springer India 2012 |

|

650 |

S. Todi and A. Bhagwati |

|

|

every year due to medical errors in hospitals. This number is more than the number of deaths due to motor vehicle accidents, breast cancer, and AIDS—three causes that receive far more public attention. This error is more evident in the critically ill patients in the ICU. Increasing accountability and demand from public and accrediting agencies have led to a movement of quality care in ICUs.

Step 1: Understand the concept of quality and safety

•Quality and safety are two sides of the same coin. Quality reflects measures that should have been taken or errors of omission, and safety reflects actions that were taken inappropriately or errors of commission.

•Case 1 may be taken as quality issue as proper precautions were not taken, which led to compromise in patient safety.

•Case 2 reflects need for preventive protocols for ventilator-associated pneumonia to be in place, another quality control issue.

•Case 3 reflects not only an error of commission, clearly a safety issue, but also lack of protocol for intravenous potassium infusion, a quality issue.

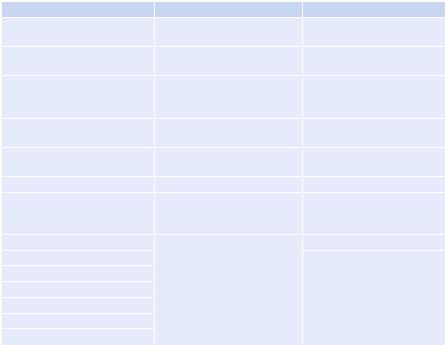

Step 2: Understand Donabedian’s theory on quality control

•Three important ingredients are as follows:

1.Structure (what we have)

2.Process (what we do)

3.Outcome (what we get)

•Structural issues consist of organizational elements, personnel, and finance and are predominantly under administrative control.

•Process issues are the care given to the patient by health care providers. Daily checklists of such issues are always helpful.

•Outcome reflects what happens to the patient from morbidity and mortality point of view, given the structure in place and processes being implemented (Tables 80.1).

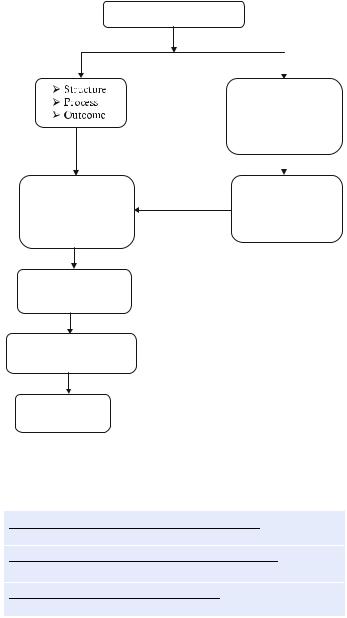

Step 3: Implement standardized data collecting and reporting system

•This should be done for all the three elements: structure, process, and outcome.

•It should follow SMART principle (specific, measurable, achievable, reliable, and time bound). A well-trained data collector is the backbone of any quality control program (Fig. 80.1).

Step 4: Understand principles of data collection

•Any data should have a numerator (affected persons) and a denominator (persons at risk) (Table 80.2).

Step 5: Prioritize

• Identify important elements for which data need to be collected (Table 80.3).

Step 6: Identify team members

•This should be done for data collection, data entry, data analysis, and data reporting.

80 Quality Control |

|

651 |

|

|

|

Table 80.1 Donabedian’s model of quality control |

|

|

Structure |

Process |

Outcome |

Closed model of ICU care |

Compliance with hand |

Crude ICU mortality |

|

hygiene |

|

Critical care consultant |

Family conference |

Risk-adjusted ICU mortality |

availability |

|

|

24 × 7 intensivist coverage |

End-of-life support policies |

Standardized mortality |

|

|

ratio = crude mortality/ |

|

|

predicted mortality |

Ward design |

Compliance with ventilator |

Hospital mortality |

|

bundle |

|

Nurse–patient ratio |

Compliance with central line |

ICU length of stay |

|

insertion bundle |

|

Doctor–patient ratio |

Antibiotic consumption |

Hospital length of stay |

Policies and protocols |

Implementation of catheter- |

Family satisfaction |

|

related blood stream infection |

|

|

prevention policies |

|

Infectious disease consultant |

Implementation of urinary |

Cost of care |

Infection control nurse |

tract infection prevention |

Resource utilization |

Multidisciplinary ward round |

policies |

|

|

|

|

Infection control committee |

|

|

Daily goal sheet |

|

|

Antibiotic form |

|

|

Adequate equipment |

|

|

Step 7: Identify benchmarks

•This should be done for comparison of data.

•There are national and international benchmarks for various quality control processes and outcomes.

•In the absence of a comparative benchmark, one can follow one’s own trend and performance over time.

Step 8: Adopt the plan-do-study-act cycle for quality control

•After identifying specific elements for data collection, collect, analyze, and compare reliable data with benchmark, take corrective action, and revisit the same process periodically to maintain a standard of care.

Step 9: Understand terminology for reporting of safety issues

•Patient safety data should be reported in the format including error, incident, near miss, adverse event, and preventable adverse event (Table 80.4).

Step 10: Implement

•One of the measures for evaluating patient safety such as incident report, root cause analysis, and failure mode effect analysis should be implemented:

652 |

S. Todi and A. Bhagwati |

|

|

Quality control and safety

Error, incident, near miss, adverse event, preventable adverse event

Team—ICU director, |

Incident report, root |

|

cause analysis, |

||

data collector, |

||

failure mode, effect |

||

statistician, residents, |

||

analysis |

||

nurses, administrator |

||

|

Data collection, entry, analysis, reporting

Compare with benchmark, own performance

Plan-do-study-act

cycle

Fig. 80.1 Quality control approach in the ICU

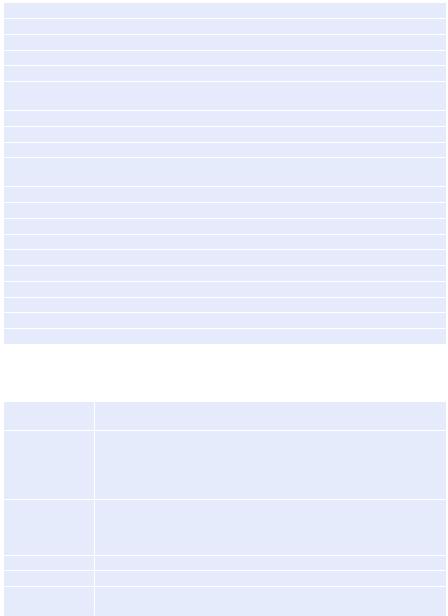

Table 80.2 Formulae for urinary tract infections, central line-associated blood stream infections, and ventilator-associated pneumonia

Number of catheter - associated urinary tract infections ´1,000

Number of urinary catheter - days

Number of central line - associated blood stream infections ´1,000

Number of central line - days

Number of ventilator - associated pneumonias ´1,000

Number of ventilator - days

–Incident report: It evaluates how a single patient comes to a harm. An incident reporting system should be voluntary, anonymous, and not linked with any form of punitive measures.

–Root cause analysis: This is a more focused enquiry on certain incidents deemed to be important for patient safety. A sentinel event is identified, and

80 Quality Control |

653 |

|

|

Table 80.3 Fundamental quality indicators

(a)Early administration of acetylsalicylic acid in acute coronary syndrome

(b)Early reperfusion techniques in ST-elevation myocardial infarction

(c)Semirecumbent position in patients undergoing invasive mechanical ventilation

(d)Prevention of thromboembolism

(e)Surgical intervention in traumatic brain injury with subdural and/or epidural hematoma

(f)Monitorization of intracranial pressure in severe traumatic brain injury with pathologic CT findings

(g)Pneumonia associated to mechanical ventilation

(h)Early management of severe sepsis/septic shock

(i)Early enteral nutrition

(j)Prophylaxis against gastrointestinal hemorrhage in patients undergoing invasive mechanical ventilation

(k)Appropriate sedation

(l)Pain management in unsedated patients

(m)Inappropriate transfusion of packed red blood cells

(n)Organ donors

(o)Compliance with hand-washing protocols

(p)Information of patients’ families in the ICU

(q)Withholding and withdrawing life support

(r)Perceived quality survey at discharge from the ICU

(s)Presence of an intensivist in the ICU 24 h/day

(t)Adverse events register

Adapted from Spanish quality control guideline

Table 80.4 Terminology for reporting adverse events

Patient safety |

Absence of the potential for, or occurrence of, health care-associated injury |

|

to patients |

Error |

It is defined as mistakes made in the process of care that result in, or have |

|

the potential to result in, harm to patients. Mistakes include the failure of a |

|

planned action to be completed as intended or the use of a wrong plan to |

|

achieve an aim. These can be the result of an action that is taken (error of |

|

commission) or an action that is not taken (error of omission) |

Incident |

Unexpected or unanticipated events or circumstances not consistent with |

|

the routine care of a particular patient, which could have, or did lead to, an |

|

unintended or unnecessary harm to a person, or a complaint, loss, or |

|

damage |

Near miss |

An occurrence of an error that did not result in harm |

Adverse event |

An injury resulting from a medical intervention |

Preventable |

Harm that could be avoided through reasonable planning or proper |

adverse event |

execution of an action |

important preventive aspects of this event are discussed by the safety team, and safeguards are implemented.

–Failure mode and effects analysis: An error-prone process is identified, and a multidisciplinary team is formed to analyze prospectively the process from multiple perspectives before a sentinel event has occurred.