- •ICU Protocols

- •Preface

- •Acknowledgments

- •Contents

- •Contributors

- •1: Airway Management

- •Suggested Reading

- •2: Acute Respiratory Failure

- •Suggested Reading

- •Suggested Reading

- •Website

- •4: Basic Mechanical Ventilation

- •Suggested Reading

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •7: Weaning

- •Suggested Reading

- •8: Massive Hemoptysis

- •Suggested Reading

- •9: Pulmonary Thromboembolism

- •Suggested Reading

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •11: Ventilator-Associated Pneumonia

- •Suggested Readings

- •12: Pleural Diseases

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •13: Sleep-Disordered Breathing

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •14: Oxygen Therapy

- •Suggested Reading

- •15: Pulse Oximetry and Capnography

- •Conclusion

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •16: Hemodynamic Monitoring

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •17: Echocardiography

- •Suggested Readings

- •Websites

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •19: Cardiorespiratory Arrest

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •20: Cardiogenic Shock

- •Suggested Reading

- •21: Acute Heart Failure

- •Suggested Reading

- •22: Cardiac Arrhythmias

- •Suggested Reading

- •Website

- •23: Acute Coronary Syndromes

- •Suggested Reading

- •Website

- •Suggested Reading

- •25: Aortic Dissection

- •Suggested Reading

- •26: Cerebrovascular Accident

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •27: Subarachnoid Hemorrhage

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •28: Status Epilepticus

- •Suggested Reading

- •29: Acute Flaccid Paralysis

- •Suggested Readings

- •30: Coma

- •Suggested Reading

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •32: Acute Febrile Encephalopathy

- •Suggested Reading

- •33: Sedation and Analgesia

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •34: Brain Death

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •35: Upper Gastrointestinal Bleeding

- •Suggested Reading

- •36: Lower Gastrointestinal Bleeding

- •Suggested Reading

- •37: Acute Diarrhea

- •Suggested Reading

- •38: Acute Abdominal Distension

- •Suggested Reading

- •39: Intra-abdominal Hypertension

- •Suggested Reading

- •Website

- •40: Acute Pancreatitis

- •Suggested Reading

- •Website

- •41: Acute Liver Failure

- •Suggested Reading

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •43: Nutrition Support

- •Suggested Reading

- •44: Acute Renal Failure

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •45: Renal Replacement Therapy

- •Suggested Reading

- •Website

- •46: Managing a Patient on Dialysis

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •47: Drug Dosing

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •48: General Measures of Infection Control

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •49: Antibiotic Stewardship

- •Suggested Reading

- •Website

- •50: Septic Shock

- •Suggested Reading

- •51: Severe Tropical Infections

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •52: New-Onset Fever

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •53: Fungal Infections

- •Suggested Reading

- •Suggested Reading

- •Website

- •55: Hyponatremia

- •Suggested Reading

- •56: Hypernatremia

- •Suggested Reading

- •57: Hypokalemia and Hyperkalemia

- •57.1 Hyperkalemia

- •Suggested Reading

- •Website

- •58: Arterial Blood Gases

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •59: Diabetic Emergencies

- •59.1 Hyperglycemic Emergencies

- •59.2 Hypoglycemia

- •Suggested Reading

- •60: Glycemic Control in the ICU

- •Suggested Reading

- •61: Transfusion Practices and Complications

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •Suggested Reading

- •Website

- •63: Onco-emergencies

- •63.1 Hypercalcemia

- •63.2 ECG Changes in Hypercalcemia

- •63.3 Superior Vena Cava Syndrome

- •63.4 Malignant Spinal Cord Compression

- •Suggested Reading

- •64: General Management of Trauma

- •Suggested Reading

- •65: Severe Head and Spinal Cord Injury

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •66: Torso Trauma

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •67: Burn Management

- •Suggested Reading

- •68: General Poisoning Management

- •Suggested Reading

- •69: Syndromic Approach to Poisoning

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •70: Drug Abuse

- •Suggested Reading

- •71: Snakebite

- •Suggested Reading

- •72: Heat Stroke and Hypothermia

- •72.1 Heat Stroke

- •72.2 Hypothermia

- •Suggested Reading

- •73: Jaundice in Pregnancy

- •Suggested Reading

- •Suggested Reading

- •75: Severe Preeclampsia

- •Suggested Reading

- •76: General Issues in Perioperative Care

- •Suggested Reading

- •Web Site

- •77.1 Cardiac Surgery

- •77.2 Thoracic Surgery

- •77.3 Neurosurgery

- •Suggested Reading

- •78: Initial Assessment and Resuscitation

- •Suggested Reading

- •79: Comprehensive ICU Care

- •Suggested Reading

- •Website

- •80: Quality Control

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •81: Ethical Principles in End-of-Life Care

- •Suggested Reading

- •82: ICU Organization and Training

- •Suggested Reading

- •Website

- •83: Transportation of Critically Ill Patients

- •83.1 Intrahospital Transport

- •83.2 Interhospital Transport

- •Suggested Reading

- •84: Scoring Systems

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •85: Mechanical Ventilation

- •Suggested Reading

- •86: Acute Severe Asthma

- •Suggested Reading

- •87: Status Epilepticus

- •Suggested Reading

- •88: Severe Sepsis and Septic Shock

- •Suggested Reading

- •89: Acute Intracranial Hypertension

- •Suggested Reading

- •90: Multiorgan Failure

- •90.1 Concurrent Management of Hepatic Dysfunction

- •Suggested Readings

- •91: Central Line Placement

- •Suggested Reading

- •92: Arterial Catheterization

- •Suggested Reading

- •93: Pulmonary Artery Catheterization

- •Suggested Reading

- •Website

- •Suggested Reading

- •95: Temporary Pacemaker Insertion

- •Suggested Reading

- •96: Percutaneous Tracheostomy

- •Suggested Reading

- •97: Thoracentesis

- •Suggested Reading

- •98: Chest Tube Placement

- •Suggested Reading

- •99: Pericardiocentesis

- •Suggested Reading

- •100: Lumbar Puncture

- •Suggested Reading

- •Website

- •101: Intra-aortic Balloon Pump

- •Suggested Reading

- •Appendices

- •Appendix A

- •Appendix B

- •Common ICU Formulae

- •Appendix C

- •Appendix D: Syllabus for ICU Training

- •Index

Acute Severe Asthma |

86 |

|

|

Krishan Chugh |

|

A 6-year-old girl developed worsening of her asthma symptoms one early morning. Her mother administered her two puffs of salbutamol with spacer. Not seeing any improvement after 15 min, she gave her two more puffs and moved her to the neighborhood nursing home. At arrival there the pediatrician found her to be dyspnoeic, diaphoretic, and unable to talk in full sentences. Auscultation of the chest revealed B/L ronchi. Her SpO2 was 90%.

Acute severe asthma results from reversible airway obstruction mostly expiratory, with main reason of obstruction being bronchospasm due to various trigger factors (such as allergens or viral respiratory infection) and inflammation of the bronchi and smaller airways. This leads to progressive hypoxemia and hypercarbia requiring bronchodilator nebulizer therapy, systemically administered anti-inflammatory agents (steroids), and sometimes mechanical ventilation.

Step 1: Initial resuscitation

Assess airway, breathing, and circulation and take resuscitative measures as described in Chap. 78.

Step 2: Assess severity of the asthmatic attack (Table 86.1)

•The rapid assessment of a child with status asthmaticus should focus on determining the severity of airway obstruction.

•Wheezing, which reflects turbulent airflow in obstructed airways, is usually equally audible on both hemithoraces. Asymmetric wheezing may imply unilateral atelectasis, pneumothorax, or foreign body. Expiratory wheezing alone is

K. Chugh, M.D. (*)

Department of Pediatrics, Institute of Child Health, Sir Ganga Ram Hospital, New Delhi, India

e-mail: chughk2000@yahoo.co.in

R. Chawla and S. Todi (eds.), ICU Protocols: A stepwise approach, |

691 |

DOI 10.1007/978-81-322-0535-7_86, © Springer India 2012 |

|

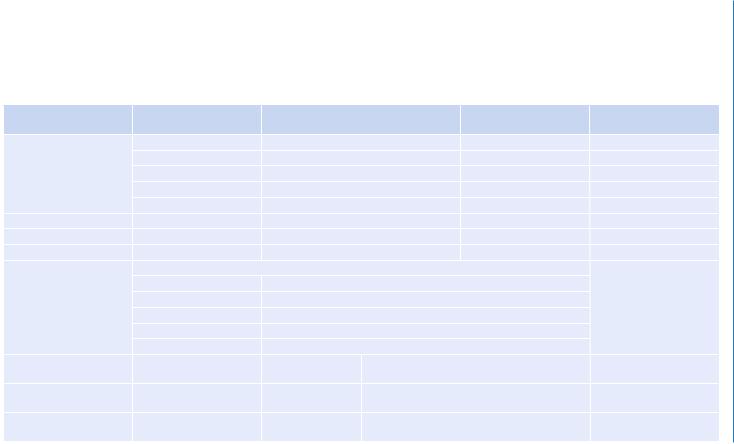

Table 86.1 Severity of asthma exacerbations |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Respiratory arrest |

|

Mild |

Moderate |

|

Severe |

imminent |

Breathing difficulty |

On walking |

On talking |

|

At rest |

|

|

|

Infant softer |

|

|

|

|

|

Shorter cry |

|

Infant stops feeding |

|

|

|

Difficult feeding |

|

|

|

|

Can lie down |

Prefers sitting |

|

Hunched forward |

|

Talk in |

Sentences |

Phrases |

|

Words |

|

Alertness |

May be agitated |

Usually agitated |

|

Usually agitated |

Drowsy or confused |

Respiratory rate |

Increased |

Increased |

|

Increased |

|

|

Normal rate of breathing in awake children: |

|

|

|

|

|

Age |

Normal rate |

|

|

|

|

<2 months |

<60/min |

|

|

|

|

2–12 months |

<50/min |

|

|

|

|

1–5 years |

<40/min |

|

|

|

|

6–8 years |

<30/min |

|

|

|

Accessory muscles and |

Usually present |

Usually present |

Usually present |

|

Paradoxical thoracoab- |

suprasternal retractions |

|

|

|

|

dominal movement |

Wheeze |

Moderate, often only end |

Loud |

Usually loud |

|

Absence of wheeze |

|

expiratory |

|

|

|

|

Pulse/min |

Mild tachycardia |

Moderate |

Severe tachycardia |

|

Bradycardia |

|

|

tachycardia |

|

|

|

692

Chugh .K

Guide to limits of normal pulse rate in children:

|

Age |

Normal rate |

|

|

|

2–12 months |

<160/min |

|

|

|

1–2 years |

<120/min |

|

|

|

2–8 years |

<110/min |

|

|

Pulsus paradoxus (can be |

Absent |

May be present |

Often present |

Absence suggests |

observed on SpO2 monitor |

<10 mmHg |

10–20 mmHg |

20–40 mmHg |

respiratory muscle fatigue |

waveform) |

|

|

|

|

Peak expiratory flow rate |

>80% |

~60–80% |

<60% predicted or |

|

(PEFR) |

|

|

personal best or response |

|

After initial bronchodila- |

|

|

lasts <2 h |

|

tor % Predicted or % |

|

|

|

|

personal best |

|

|

|

|

PaO2 (on air) |

Normal |

>60 mmHg |

<60 mmHg |

|

|

|

|

Possible cyanosis |

|

And/or PaCO2 |

<45 mmHg |

<45 mmHg |

>45 mmHg |

|

|

|

|

Possible respiratory |

|

|

|

|

failure |

|

SaO2% (on air) |

>95% |

91–95% |

<90% |

|

Hypercapnia (hypoventilation) develops more readily in young children than in adults and adolescents

Asthma Severe Acute 86

693

694 |

K. Chugh |

|

|

found in mild-to-moderate illness, whereas expiratory plus inspiratory wheezing is present in moderate-to-severe status asthmaticus.

•The silent chest is an ominous sign and may indicate either pneumothorax or the complete absence of airflow due to severe airway obstruction and imminent respiratory failure.

•Blood gas analysis may support the clinical judgment of severity; an increasing

level of CO2 is an ominous sign. During a moderate asthma attack, a capillary blood gas analysis may be sufficient; in patients admitted to an intensive care unit, arterial blood gas analyses should be a routine. Sequential measurements are important as respiratory alkalosis with hypocarbia is common during the early phases of an asthma attack, while normalization and a subsequent increase

in the PaCO2 may be important indicators of clinical deterioration. Thus, a normal PaCO2 with even borderline low PaO2 indicates a phase of rising PaCO2, hence, need for more intensive therapy.

•A chest X-ray may be relevant in search for underlying complications such as pneumonia or air leakages.

Step 3: Review ongoing treatment

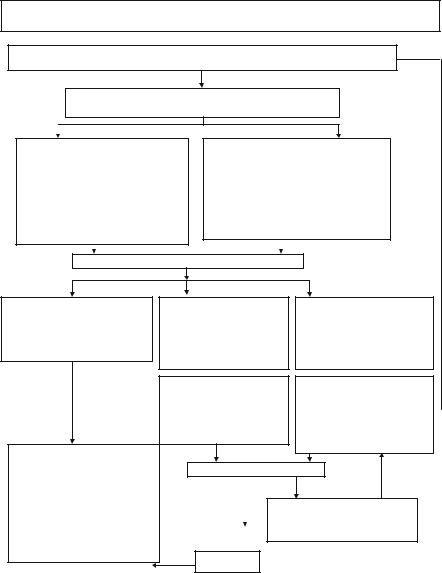

•Take into consideration the treatment that the child may have received in the past few hours. This helps us in deciding where in the treatment algorithm (Fig. 86.1) we should start. For example, in a child who has received several doses of salbutamol in the past 1 h, it may be futile to begin treatment at the top end of the algorithm.

Step 4: Start treatment (Fig. 86.1)

•Follow the algorithm for treatment.

•Generally children tolerate repeated doses of salbutamol very well and tachycardia as a side effect is less worrisome.

Step 5: Monitor closely

•At all stages, the child should be constantly monitored and escalation or deescalation of therapy should be done accordingly. For example, a child who is showing signs of exhaustion may have to be intubated straightaway even if IV b-agonist or aminophylline has not yet been tried.

Step 6: Further treatment

•Intravenous ketamine can be tried in children who are not improving on intravenous b-agonist, intravenous steroids, and supportive therapy. It is a sedative that has bronchodilator properties. Generally, it is started in the dose of 1 mg/kg/h after a loading dose of 1 mg/kg. The infusion can be increased to 3 mg/kg/h. However, all preparations should have been made for intubation and ventilation before starting IV ketamine.

86 Acute Severe Asthma |

695 |

|

|

Management of Asthma Exacerbations In The Acute Care Setting

Initial assessment, Initial treatment (If in acute respiratory failure/ critical admit in PICU directly)

Reassess after 1 hour

Physical examination, PEF, O2 saturation and other tests as needed

Criteria for moderate episode:

PEF 60-80% predicted/personal best Physical examination: moderate symptoms, accessory muscle use

Treatment:

O2

Inhaled β2 agonist and inhaled anticholingergic every 60 min

Oral glucocorticosteroids

Continue treatment for 1-3 h, provided there is improvement

Criteria for severe episode:

History of risk factors for near fatal asthma PEF< 60% predicted/personal best

Physical examination: severe symptoms at rest, chest retraction

No improvement after initial treatment Treatment:

Inhaled B agonist and inhaled anticholingergic Systemic glucocorticosteroids

Reassess after 1-2 hr

Good response within 1-2 hr Response sustained 60 min after last

treatment

Physical examination normal: no distress PEF>70%

O2 saturation>95%

Improved: criteria for discharge home PEF>60% predicted/personal best Response Sustained on oral/inhaled medication

Home treatment:

Continue inhaled β2-agonist Consider, in most cases oral steroid

Consider adding a combination inhlaler Patient education:

Take medicine correctly Review action plan Close medical follow up

Incomplete response within 1-2 hr Risk factors for near –fatal asthma Physical examination: mild to moderate signs

PEF <60%

O2 saturation not improving

Admit to acute care setting

O2

Inhaled B agonist +/− antichlinergic Systemic glucocorticosteroid Intravenous magnesium

Monitor PEF,O2 saturation, pulse

Poor response within 1-2 hr

Risk factors for near fatal asthma Physical examination: symptoms severe, drowsiness, confusion PEF <30%

Pco2 > 45mmHg Po2< 60mmHg

Admit to intensive care

O2

Inhaled β2 agonist plus anticholinergic Intravenous glucocorticosteroids  Consider intravenous β2 agonist Consider intravenous aminophylline Possible intubation and mechanical ventilation

Consider intravenous β2 agonist Consider intravenous aminophylline Possible intubation and mechanical ventilation

Reassess at intervals

Poor response (see above)

Admit to intensive care

Incomplete response in 6-12 hr(see above)

Consider admission to intensive care

Improved

Fig. 86.1 Management of asthma exacerbations in the acute care setting

Step 7: Assess the need for intubation and ventilation

•Generally, decision to intubate and ventilate an asthmatic child is made on clinical grounds.

•Thus, cardiac arrest, respiratory arrest or severe bradypnea, extreme physical exhaustion, and altered sensorium are taken as absolute indications.