- •ICU Protocols

- •Preface

- •Acknowledgments

- •Contents

- •Contributors

- •1: Airway Management

- •Suggested Reading

- •2: Acute Respiratory Failure

- •Suggested Reading

- •Suggested Reading

- •Website

- •4: Basic Mechanical Ventilation

- •Suggested Reading

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •7: Weaning

- •Suggested Reading

- •8: Massive Hemoptysis

- •Suggested Reading

- •9: Pulmonary Thromboembolism

- •Suggested Reading

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •11: Ventilator-Associated Pneumonia

- •Suggested Readings

- •12: Pleural Diseases

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •13: Sleep-Disordered Breathing

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •14: Oxygen Therapy

- •Suggested Reading

- •15: Pulse Oximetry and Capnography

- •Conclusion

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •16: Hemodynamic Monitoring

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •17: Echocardiography

- •Suggested Readings

- •Websites

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •19: Cardiorespiratory Arrest

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •20: Cardiogenic Shock

- •Suggested Reading

- •21: Acute Heart Failure

- •Suggested Reading

- •22: Cardiac Arrhythmias

- •Suggested Reading

- •Website

- •23: Acute Coronary Syndromes

- •Suggested Reading

- •Website

- •Suggested Reading

- •25: Aortic Dissection

- •Suggested Reading

- •26: Cerebrovascular Accident

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •27: Subarachnoid Hemorrhage

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •28: Status Epilepticus

- •Suggested Reading

- •29: Acute Flaccid Paralysis

- •Suggested Readings

- •30: Coma

- •Suggested Reading

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •32: Acute Febrile Encephalopathy

- •Suggested Reading

- •33: Sedation and Analgesia

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •34: Brain Death

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •35: Upper Gastrointestinal Bleeding

- •Suggested Reading

- •36: Lower Gastrointestinal Bleeding

- •Suggested Reading

- •37: Acute Diarrhea

- •Suggested Reading

- •38: Acute Abdominal Distension

- •Suggested Reading

- •39: Intra-abdominal Hypertension

- •Suggested Reading

- •Website

- •40: Acute Pancreatitis

- •Suggested Reading

- •Website

- •41: Acute Liver Failure

- •Suggested Reading

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •43: Nutrition Support

- •Suggested Reading

- •44: Acute Renal Failure

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •45: Renal Replacement Therapy

- •Suggested Reading

- •Website

- •46: Managing a Patient on Dialysis

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •47: Drug Dosing

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •48: General Measures of Infection Control

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •49: Antibiotic Stewardship

- •Suggested Reading

- •Website

- •50: Septic Shock

- •Suggested Reading

- •51: Severe Tropical Infections

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •52: New-Onset Fever

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •53: Fungal Infections

- •Suggested Reading

- •Suggested Reading

- •Website

- •55: Hyponatremia

- •Suggested Reading

- •56: Hypernatremia

- •Suggested Reading

- •57: Hypokalemia and Hyperkalemia

- •57.1 Hyperkalemia

- •Suggested Reading

- •Website

- •58: Arterial Blood Gases

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •59: Diabetic Emergencies

- •59.1 Hyperglycemic Emergencies

- •59.2 Hypoglycemia

- •Suggested Reading

- •60: Glycemic Control in the ICU

- •Suggested Reading

- •61: Transfusion Practices and Complications

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •Suggested Reading

- •Website

- •63: Onco-emergencies

- •63.1 Hypercalcemia

- •63.2 ECG Changes in Hypercalcemia

- •63.3 Superior Vena Cava Syndrome

- •63.4 Malignant Spinal Cord Compression

- •Suggested Reading

- •64: General Management of Trauma

- •Suggested Reading

- •65: Severe Head and Spinal Cord Injury

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •66: Torso Trauma

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •67: Burn Management

- •Suggested Reading

- •68: General Poisoning Management

- •Suggested Reading

- •69: Syndromic Approach to Poisoning

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •70: Drug Abuse

- •Suggested Reading

- •71: Snakebite

- •Suggested Reading

- •72: Heat Stroke and Hypothermia

- •72.1 Heat Stroke

- •72.2 Hypothermia

- •Suggested Reading

- •73: Jaundice in Pregnancy

- •Suggested Reading

- •Suggested Reading

- •75: Severe Preeclampsia

- •Suggested Reading

- •76: General Issues in Perioperative Care

- •Suggested Reading

- •Web Site

- •77.1 Cardiac Surgery

- •77.2 Thoracic Surgery

- •77.3 Neurosurgery

- •Suggested Reading

- •78: Initial Assessment and Resuscitation

- •Suggested Reading

- •79: Comprehensive ICU Care

- •Suggested Reading

- •Website

- •80: Quality Control

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •81: Ethical Principles in End-of-Life Care

- •Suggested Reading

- •82: ICU Organization and Training

- •Suggested Reading

- •Website

- •83: Transportation of Critically Ill Patients

- •83.1 Intrahospital Transport

- •83.2 Interhospital Transport

- •Suggested Reading

- •84: Scoring Systems

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •85: Mechanical Ventilation

- •Suggested Reading

- •86: Acute Severe Asthma

- •Suggested Reading

- •87: Status Epilepticus

- •Suggested Reading

- •88: Severe Sepsis and Septic Shock

- •Suggested Reading

- •89: Acute Intracranial Hypertension

- •Suggested Reading

- •90: Multiorgan Failure

- •90.1 Concurrent Management of Hepatic Dysfunction

- •Suggested Readings

- •91: Central Line Placement

- •Suggested Reading

- •92: Arterial Catheterization

- •Suggested Reading

- •93: Pulmonary Artery Catheterization

- •Suggested Reading

- •Website

- •Suggested Reading

- •95: Temporary Pacemaker Insertion

- •Suggested Reading

- •96: Percutaneous Tracheostomy

- •Suggested Reading

- •97: Thoracentesis

- •Suggested Reading

- •98: Chest Tube Placement

- •Suggested Reading

- •99: Pericardiocentesis

- •Suggested Reading

- •100: Lumbar Puncture

- •Suggested Reading

- •Website

- •101: Intra-aortic Balloon Pump

- •Suggested Reading

- •Appendices

- •Appendix A

- •Appendix B

- •Common ICU Formulae

- •Appendix C

- •Appendix D: Syllabus for ICU Training

- •Index

Arterial Catheterization |

92 |

|

Sheila Nainan Myatra, Parvez Ali Khan,

and Jigeeshu V. Divatia

A 65-year-old diabetic male patient was admitted to the ICU with a right lobar pneumonia. He was started on antibiotic therapy. He was receiving oxygen by a mask at 8 L/min and maintaining an SpO2 of 94%. His blood pressure was being monitored every 10 min using noninvasive blood pressure measurement. By evening his blood pressure started to drop. Noninvasive blood pressure reading was 80/50 mmHg at 8 PM, which was not responding to fluid boluses.

Invasive arterial pressure monitoring, using arterial catheterization, is one of the commonly performed bedside procedures in the ICU during shock, when noninvasive blood pressure monitoring becomes unreliable. This chapter describes the indications, contraindications, preparation, procedural details, and maintenance of the catheter in detail along with the complications that can arise from arterial catheterization.

Step 1: Assess the need for intra-arterial pressure monitoring indications

•Hemodynamic instability

•Need for frequent blood pressure monitoring during vasopressor therapy

•Need for frequent arterial blood gas analysis

S.N. Myatra, M.D. (*)

Department of Anaesthesia, Critical Care and Pain, Tata Memorial Hospital, Mumbai, India e-mail: sheila150@hotmail.com

P.A. Khan, M.D.

Department of Critical Care and Anaesthesia, Tata Memorial Hospital, Mumbai, India

J.V. Divatia, M.D., F.I.S.C.C.M.

Department of Anaesthesiology, Critical Care and Pain, Tata Memorial Hospital, Mumbai, India

R. Chawla and S. Todi (eds.), ICU Protocols: A stepwise approach, |

735 |

DOI 10.1007/978-81-322-0535-7_92, © Springer India 2012 |

|

736 |

S.N. Myatra et al. |

|

|

Step 2: Check for any contraindications

•Inadequate circulation to the extremity

•Uncontrolled coagulopathy

•Extremities with full-thickness burn or trauma

•Skin infection over the insertion site

•Raynaud’s phenomenon

•Thromboangiitis obliterans (Buerger’s disease)

•Locations near arteriovenous fistulas

Step 3: Choose the appropriate site

•The radial artery at the wrist is the most preferred site as the hand has usually good collateral supply, and it is easy to access and maintain.

•Acceptable alternate sites commonly used in adult patients include the femoral, axillary, brachial, and dorsalis pedis arteries.

•All sites are at a risk of ischemic complications due to their small caliber (radial and dorsalis pedis), lack of good collateral supply (brachial and axillary), and presence of atherosclerotic vascular disease (femoral and dorsalis).

•Although infectious complications may be higher with the femoral artery, this may be the only palpable artery amenable to cannulation during severe hypotension. Ultrasound guidance may be useful in locating and cannulating the femoral artery.

•Keeping in mind the above, always choose an artery you are familiar with cannulating.

Step 4: Check perfusion of the extremity

•Both the necessity and the optimal method to assess adequacy of collateral blood flow to the hand before radial artery cannulation are controversial.

•To perform an Allen’s test:

–The patient’s hand should be elevated above his or her heart.

–The patient should be asked to make a fist.

–Pressure should be applied to both the radial and the ulnar artery until distal blood flow is occluded.

–While maintaining the elevated hand position, the patient should then open the hand. The hand should appear pale and have limited capillary refills.

–The ulnar arterial pressure should be released (while maintaining enough pressure to occlude the radial artery).

–The hand should return to normal color within 5–7 s.

–Delayed return suggests poor collateral circulation

–The test should then be performed on the radial artery circulation in the same manner.

•There is lack of evidence that these tests can predict hand ischemia after radial artery cannulation. Although the value of these tests has not been established, it may provide some qualitative assessment of collateral circulation.

•To make the interpretation more objective, pulse oximetry, plethysmography, or Doppler ultrasound examination may be used along with the modified Allen’s test.

•The operator should document the impression of collateral circulation in the procedure note.

92 Arterial Catheterization |

737 |

|

|

Step 5: Keep all equipment ready for arterial cannulation and pressure transducing

•Material for sterile preparation

•A wrist board or roller pad under the wrist, 25-gauge needles, and syringes with 1% lidocaine

•An arterial catheter and wire set/arterial cannulae (cannulae for arterial placement should be without an injection port and preferably have an eye to take a stitch)

•A needle holder with suture material

•Sterile dressing

•An arterial connector

•A pressure transducing system

Step 6: Set up the pressure transducing system

This consists of a pressure transducing assembly with a flushing system. The accuracy of the intra-arterial blood pressure measurement will depend on the proper setup and function of the pressure transducing system.

•The pressure transducing assembly consists of a coupling system, pressure transducer, amplifier, signal conditioner, analog to digital converter, and microprocessor that converts the signal received from the artery into a waveform on the a bedside monitor.

•The flushing system is set up using a 500-mL saline bottle encased in a bag pressurized to 300 mmHg. At this pressure, the catheter will be flushed with 3 mL saline per hour and help keep the catheter patent. Using the flushing device helps flush the assembly as required.

Before connecting flush the pressure transducing system with saline using the flushing device, remove all air bubbles, and keep it ready to connect to the arterial catheter. Heparinized saline is no longer routinely used in view of concerns about heparin-induced thrombocytopenia. Also, continuous heparin flush solution has been shown to affect coagulation studies if the sample is drawn via the arterial line.

Step 7: Positioning and preparation prior to radial artery cannulation

•Inform the patient about the procedure (if conscious) and take the informed consent.

•Don the mask, cap, sterile gown, and gloves.

•Position the wrist in dorsiflexion. This brings the radial artery in closer approximation to the skin and can be instrumental in success of the procedure.

•This position can be maintained using a roll of gauze below the wrist or with a specially designed arm board and securing the arm with tape.

•The field can be sterilely prepared and draped using towels. In all invasive procedures, meticulous care should be taken to minimize the risk of infection.

•A small wheal of 1% lidocaine should be raised in the conscious patient to decrease the pain during cannulation.

738 |

S.N. Myatra et al. |

|

|

Step 8: Radial arterial cannulation

Two types of arterial catheters are used commonly:

•Catheter with needle

•Catheter with needle and a guidewire

The radial artery is palpated between the distal radius and the flexor carpi ulnaris

tendon. The arterial catheter with needle is inserted at a 30to 45-degree angle toward the artery.

Over-the-Needle Technique

Once there is blood return, the needle is advanced slightly further to ensure the catheter has entered the vessel. The needle angle is then lowered to 10–15°, and the catheter is guided over the needle and advanced into the vessel.

Over-the-Wire Technique

•When blood return is noted, the catheter is advanced further, and the needle is then removed. The guidewire is then kept ready, and the catheter is withdrawn till there is pulsatile blood flow. The guidewire is inserted into the vessel, the catheter is advanced over it, and then the guidewire is removed.

•A commonly used variant of this technique is to initially insert only the introducer needle without catheter and then advance guidewire through the needle when in position and finally thread arterial catheter over the guidewire.

Anticipated Difficulties During Cannulation

•In the over-the-needle technique, sometimes there is a blood return, but the artery cannot be cannulated. This may be because the needle has entered the vessel, but the catheter is still outside it. This can be overcome by advancing the needle further and then guiding the catheter over it or removing the needle and passing a guidewire into the vessel over which the catheter can be advanced easily.

•Sometimes the catheter may not easily pass through the skin. To overcome this, make a small nick on the skin with a needle or a blade at the insertion site.

•After multiple attempts at cannulation, the artery may go into spasm. Change the site for arterial line placement at this point.

After cannulation, pressure is given on the artery proximal to the catheter tip to

reduce bleeding while the pressure transuding assembly is connected.

Step 9: Secure the catheter and check perfusion

•Great care should be taken to make sure the catheter stays in place. Although there are various ways of fixing the catheter with adhesive tape, the best method of securing it is to suture it in place. A moderate-diameter, nonabsorbable suture material can be used.

•Place a clear dressing over the catheter, which will not only secure it further but also allow inspection of the insertion site.

•Label and date the arterial line.

•Immediately after cannulation, check perfusion of the extremity. This should also be checked periodically when the arterial catheter is in place.

92 Arterial Catheterization |

739 |

|

|

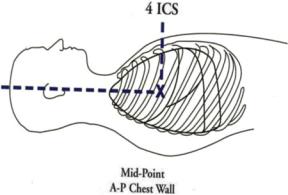

Fig. 92.1 Phlebostatic axis

Step 10: Zero and level the transducer (static calibration)

•To obtain accurate pressure measurements, the air-fluid interface must be aligned with the chamber or vessel being measured.

•The reference point is usually at the level of the heart. Use the phlebostatic axis (junction of the fourth intercostal space and midpoint between the anterior and posterior chest walls—Fig. 92.1).

•A spirit level should be used to level this point with the stopcock of the pressure transducing system, which is used for zeroing.

•The transducer is opened to air and the recorded pressure (atmospheric pressure) is used by convention as 0 mmHg reference value.

Step 11: Check if the system is optimally damped (dynamic calibration)

•Damping indicates the tendency of an oscillating system to return to its resting state. Anything that takes energy out of the system results in a progressive diminution of amplitude of oscillations.

•Underdamped waveforms (will be narrow and peaked tracing and will record higher systolic and lower diastolic pressure) are seen when long tubing is used or with increased vascular resistance.

•Overdamped waveforms (will record lower systolic and higher diastolic pressure) are commonly seen when there are air bubbles or blood clots, overly compliant tubing, catheter kinks, stopcocks, no fluid in the flush bag, or low flush bag pressure.

•In both the above, the mean arterial pressure (MAP) will not change. Hence, always rely on the MAP, especially when you are not sure whether the system is optimally damped.

•Damping can be checked by doing a “square wave test” (Fig. 92.2). Activate the flush device, quickly release it, and observe the waveform on the monitor. The waveform will sharply rise and “square off” at the top when the flush is activated and then the tracing returns to the baseline after it is released (Fig. 92.2). Check the number of oscillations:

740 |

S.N. Myatra et al. |

|

|

Fig. 92.2 Square wave test

1. Optimally damped—one or two oscillations before return to tracing 2. Underdamped—more than two oscillations before return to tracing 3. Overdamped—less than one oscillation before return to tracing

Repeat the square wave test every 8–12 h, whenever the waveform looks overor underdamped, when the accuracy of the measurement is doubtful, especially when you are implementing some interventions based on intra-arterial pressure values.

Step 12: Check the arterial waveform and MAP (Fig. 92.3)

•Arterial pressure waveforms differ from site to site. As the arterial pressure is recorded more distally, the trace gets progressively more peaked and the dicrotic notch migrates away from the peak. The MAP however does not vary widely as one measures more distally.

•An underor overdamped tracing can either underor overestimate the systolic and diastolic pressures. However, the MAP always remains the same.

•Considering the above, always use and rely on only the MAP rather than the systolic or diastolic pressure recorded during intra-arterial blood pressure monitoring.

Fig. 92.3 Components of the arterial waveform (1—peak systolic pressure, 2—dicrotic notch, 3—diastolic pressure, and 4—anacrotic notch)

92 Arterial Catheterization |

741 |

|

|

Step 13: Make other interpretations from the arterial waveform

Besides more accurate and real-time recording of arterial pressure, a lot of hemodynamic interpretations can be made from the arterial waveform:

•Systolic blood pressure variations (swing in the waveform) can be seen during hypovolemia.

•Steep slope of upstroke means good contractility and vice versa.

•Area under the curve represents the stroke volume.

•Position of the dicrotic notch—low (low systemic vascular resistance) and high (high afterload).

•Slope of the decent—steep (low systemic vascular resistance).

Step 14: Optimize the natural frequency of the system to improve accuracy

•Use a wide-bore, high-pressure tubing no longer than 122 cm (48 in.).

•Avoid tubing extensions and stopcocks.

•All connections should be tight.

•Eliminate air bubbles.

•Ensure that the flush bag external pressure is 300 mmHg.

•Keep cannulated extremity in neutral or slightly extended position.

Step 15: Ensure proper maintenance of the Arterial catheter

•Ensure that the catheter is labeled and has an insertion date at all times.

•Check perfusion of the extremity at regular intervals.

•Check the insertion site daily through the clear dressing for signs of inflammation and infection.

•Change dressing only if it is not well coated, very dirty, or there is collection under it.

•Whenever the arterial catheter is not being transduced, block it using an arterial connector (not venous connectors /stopcocks). These provide high resistance to the blood flow into the catheter and prevent them from getting blocked.

Step 16: Watch for complications

•Vascular complications of clinical significance are rare but can be devastating. Attention to the adequacy of distal perfusion is of great importance.

•Absent pulse, dampened waveform, blanched or mottled skin, delayed capillary refill, and painful and cold hands or fingers with motor weakness are presentations of hand ischemia.

•Infections complications: Arterial catheters can be responsible for both local and catheter-related bloodstream infections, though the incidence is low. The arterial catheter should be given the same degree of importance as the central venous catheter as a potential source of sepsis. Remove the catheter if it is suspected to be the cause of infection.

•Bleeding, hematoma.

•Nerve damage.

•Pseudoaneurysm.