- •ICU Protocols

- •Preface

- •Acknowledgments

- •Contents

- •Contributors

- •1: Airway Management

- •Suggested Reading

- •2: Acute Respiratory Failure

- •Suggested Reading

- •Suggested Reading

- •Website

- •4: Basic Mechanical Ventilation

- •Suggested Reading

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •7: Weaning

- •Suggested Reading

- •8: Massive Hemoptysis

- •Suggested Reading

- •9: Pulmonary Thromboembolism

- •Suggested Reading

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •11: Ventilator-Associated Pneumonia

- •Suggested Readings

- •12: Pleural Diseases

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •13: Sleep-Disordered Breathing

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •14: Oxygen Therapy

- •Suggested Reading

- •15: Pulse Oximetry and Capnography

- •Conclusion

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •16: Hemodynamic Monitoring

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •17: Echocardiography

- •Suggested Readings

- •Websites

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •19: Cardiorespiratory Arrest

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •20: Cardiogenic Shock

- •Suggested Reading

- •21: Acute Heart Failure

- •Suggested Reading

- •22: Cardiac Arrhythmias

- •Suggested Reading

- •Website

- •23: Acute Coronary Syndromes

- •Suggested Reading

- •Website

- •Suggested Reading

- •25: Aortic Dissection

- •Suggested Reading

- •26: Cerebrovascular Accident

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •27: Subarachnoid Hemorrhage

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •28: Status Epilepticus

- •Suggested Reading

- •29: Acute Flaccid Paralysis

- •Suggested Readings

- •30: Coma

- •Suggested Reading

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •32: Acute Febrile Encephalopathy

- •Suggested Reading

- •33: Sedation and Analgesia

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •34: Brain Death

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •35: Upper Gastrointestinal Bleeding

- •Suggested Reading

- •36: Lower Gastrointestinal Bleeding

- •Suggested Reading

- •37: Acute Diarrhea

- •Suggested Reading

- •38: Acute Abdominal Distension

- •Suggested Reading

- •39: Intra-abdominal Hypertension

- •Suggested Reading

- •Website

- •40: Acute Pancreatitis

- •Suggested Reading

- •Website

- •41: Acute Liver Failure

- •Suggested Reading

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •43: Nutrition Support

- •Suggested Reading

- •44: Acute Renal Failure

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •45: Renal Replacement Therapy

- •Suggested Reading

- •Website

- •46: Managing a Patient on Dialysis

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •47: Drug Dosing

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •48: General Measures of Infection Control

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •49: Antibiotic Stewardship

- •Suggested Reading

- •Website

- •50: Septic Shock

- •Suggested Reading

- •51: Severe Tropical Infections

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •52: New-Onset Fever

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •53: Fungal Infections

- •Suggested Reading

- •Suggested Reading

- •Website

- •55: Hyponatremia

- •Suggested Reading

- •56: Hypernatremia

- •Suggested Reading

- •57: Hypokalemia and Hyperkalemia

- •57.1 Hyperkalemia

- •Suggested Reading

- •Website

- •58: Arterial Blood Gases

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •59: Diabetic Emergencies

- •59.1 Hyperglycemic Emergencies

- •59.2 Hypoglycemia

- •Suggested Reading

- •60: Glycemic Control in the ICU

- •Suggested Reading

- •61: Transfusion Practices and Complications

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •Suggested Reading

- •Website

- •63: Onco-emergencies

- •63.1 Hypercalcemia

- •63.2 ECG Changes in Hypercalcemia

- •63.3 Superior Vena Cava Syndrome

- •63.4 Malignant Spinal Cord Compression

- •Suggested Reading

- •64: General Management of Trauma

- •Suggested Reading

- •65: Severe Head and Spinal Cord Injury

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •66: Torso Trauma

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •67: Burn Management

- •Suggested Reading

- •68: General Poisoning Management

- •Suggested Reading

- •69: Syndromic Approach to Poisoning

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •70: Drug Abuse

- •Suggested Reading

- •71: Snakebite

- •Suggested Reading

- •72: Heat Stroke and Hypothermia

- •72.1 Heat Stroke

- •72.2 Hypothermia

- •Suggested Reading

- •73: Jaundice in Pregnancy

- •Suggested Reading

- •Suggested Reading

- •75: Severe Preeclampsia

- •Suggested Reading

- •76: General Issues in Perioperative Care

- •Suggested Reading

- •Web Site

- •77.1 Cardiac Surgery

- •77.2 Thoracic Surgery

- •77.3 Neurosurgery

- •Suggested Reading

- •78: Initial Assessment and Resuscitation

- •Suggested Reading

- •79: Comprehensive ICU Care

- •Suggested Reading

- •Website

- •80: Quality Control

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •81: Ethical Principles in End-of-Life Care

- •Suggested Reading

- •82: ICU Organization and Training

- •Suggested Reading

- •Website

- •83: Transportation of Critically Ill Patients

- •83.1 Intrahospital Transport

- •83.2 Interhospital Transport

- •Suggested Reading

- •84: Scoring Systems

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •85: Mechanical Ventilation

- •Suggested Reading

- •86: Acute Severe Asthma

- •Suggested Reading

- •87: Status Epilepticus

- •Suggested Reading

- •88: Severe Sepsis and Septic Shock

- •Suggested Reading

- •89: Acute Intracranial Hypertension

- •Suggested Reading

- •90: Multiorgan Failure

- •90.1 Concurrent Management of Hepatic Dysfunction

- •Suggested Readings

- •91: Central Line Placement

- •Suggested Reading

- •92: Arterial Catheterization

- •Suggested Reading

- •93: Pulmonary Artery Catheterization

- •Suggested Reading

- •Website

- •Suggested Reading

- •95: Temporary Pacemaker Insertion

- •Suggested Reading

- •96: Percutaneous Tracheostomy

- •Suggested Reading

- •97: Thoracentesis

- •Suggested Reading

- •98: Chest Tube Placement

- •Suggested Reading

- •99: Pericardiocentesis

- •Suggested Reading

- •100: Lumbar Puncture

- •Suggested Reading

- •Website

- •101: Intra-aortic Balloon Pump

- •Suggested Reading

- •Appendices

- •Appendix A

- •Appendix B

- •Common ICU Formulae

- •Appendix C

- •Appendix D: Syllabus for ICU Training

- •Index

Acute Coronary Syndromes |

23 |

|

|

Rajesh Rajani and Farhad N. Kapadia |

|

A previously healthy smoker presented with severe chest pain to the emergency department. On arrival he was clinically stable. The ECG showed ST-segment elevation in the anterior leads and blood test showed elevated troponin T and CK-MB. The echocardiograph showed hypokinesia in the anteroseptal region. In the emergency department, his symptoms progressively worsened with ongoing intense chest pain, and he became increasingly restless and breathless.

Acute coronary syndrome (ACS) is a common diagnosis in patients presenting to the emergency department with acute onset chest pain. Timely and appropriate management in a protocolized manner is mandatory to salvage patients from this life-threatening syndrome.

Step 1: Initiate resuscitation

•Patients with acute chest pain should have immediate intravenous access as they may deteriorate suddenly.

•A continuous ECG monitor and pulse oximeter should be placed. Give oxygen and assist breathing if needed.

•In the case of cardiac arrest, follow ACLS (advanced cardiac life support) protocol (see Chap. 19).

•Cardiovert immediately if ventricular or atrial tachyarrhythmia is detected and patient is hemodynamically unstable (shock or pulmonary edema).

R. Rajani, M.D., D.M. (*)

P.D. Hinduja Hospital and Medical Research Centre, Mumbai, India e-mail: rrajani20@gmail.com

F.N. Kapadia, M.D., F.R.C.P.

P.D. Hinduja National Hospital and Medical Research Centre,

Mumbai, India

R. Chawla and S. Todi (eds.), ICU Protocols: A stepwise approach, |

185 |

DOI 10.1007/978-81-322-0535-7_23, © Springer India 2012 |

|

186 |

R. Rajani and F.N. Kapadia |

|

|

Urgent transcutaneous or temporary intravenous pacing is required if severe symptomatic bradycardia is not responding to intravenous atropine.

Step 2: Take focused history and perform physical examination

•Elaborate the symptom of chest pain—site, type, severity, relation to exertion

•Sweating

•Cardiorespiratory symptoms

•Symptoms of low output state such as fatigue, dizziness, and syncope

•Risk factors for ischemic heart disease—hypertension, diabetes, hyperlipidemia, smoking, positive family history

•History of bleeding diathesis or recent blood loss

•BP in both arms

•Palpate all peripheral and central pulses

•Auscultate the heart for gallop or murmurs

•Auscultate the chest for basal crepitations

Step 3: Perform basic investigation

•12-lead ECG

–Look for features of new ST elevation acute myocardial infarction (STEMI)

•New ST elevation in two or more contiguous leads (inferior or anterior) Threshold values for new ST-segment elevation consistent with STEMI are:

–J-point elevation 0.2 mV (2 mm) in leads V2 and V3 and 0.1 mV (1 mm) in all other leads (men more than 40 years old)

– J-point elevation 0.25 mV (2.5 mm) in leads V2 and V3 and

0.1 mV(1 mm) in all other leads (men less than 40 years old)

–J-point elevation 0.15 mV (1.5 mm) in leads V2 and V3 and 0.1 mV (1 mm) in all other leads (women)

•New LBBB (left bundle branch block)

•ST elevation in right precordial leads V4r for right ventricular myocardial infarction (MI)

•ST depression in precordial leads (V1–V3) for posterior MI

•Pathological “Q” waves

–Echocardiogram

•Regional wall motion abnormality

•Poor ejection fraction

•Mechanical complication–papillary muscle rupture, VSD

–Chest X-ray

•Cardiomegaly

•Pulmonary congestion

–Cardiac enzymes

•Raised troponins, CPK-MB

–A complete blood count

•Leukocytosis in MI

–Platelet count, prothrombin time, activated partial thromboplastin time (APTT)

–Liver and renal function test

–Electrolytes

•Look for hypokalemia, hypomagnesemia

23 Acute Coronary Syndromes |

187 |

|

|

Table 23.1 Causes of acute |

Life-threatening causes |

chest pain |

ACS (unstable angina, NSTEMI, STEMI) |

|

|

|

Pulmonary embolus (may be associated with ↑ troponin) |

|

Aortic dissection (may be overlooked due to associated MI) |

|

“Benign” causes |

|

Pericarditis (both ↑ troponin and ST elevation may occur) |

|

Gastrointestinal (esophageal reflux, spasm) |

|

Musculoskeletal (e.g., costochondritis) |

|

Neurologic (cervical radiculopathy, herpes zoster) |

Table 23.2 Causes of raised troponin

ACS (unstable angina, NSTEMI, STEMI)

Pulmonary embolism

Chronic renal insufficiency

Intracranial hemorrhage

Ingestion of sympathomimetic agents

Cardiac contusion

DC cardioversion

Cardiac infiltrative disorder

Chemotherapy

Myocarditis/pericarditis

Cardiac transplantation

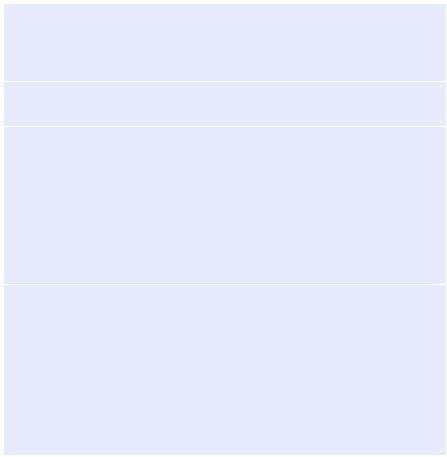

Step 4: Confirm diagnosis of ACS

•Typical chest pain in patients at risk of myocardial ischemia with classical ECG changes and raised cardiac enzymes establishes diagnosis in many cases.

•Consider other causes of chest pain (Table 23.1).

•Consider other causes of raised troponin (Table 23.2).

•Occasional patients have typical chest pain without ECG abnormalities or atypical chest pain (diabetics, female, elderly) and nonspecific changes on ECG. In these situations, perform serial monitoring of ECG and cardiac enzymes. An early echo is useful to look for regional wall motion abnormalities.

Step 5: Give pain relief

•Sublingual nitroglycerine (0.3–0.6 mg) may be repeated twice or thrice or as an intravenous infusion (5–200 mcg/min) or as a transdermal patch.

•Avoid nitrates in the following situations:

–Hypotension (systolic <90 mmHg) or fall of more than 30 mmHg from baseline

–Bradycardia (<50/min)

–Intake of phosphodiesterase inhibitors like sildenafil for erectile dysfunction in the previous 24–48 h

–In patients with inferior wall MI and suspected right ventricular (RV) involvement because these patients require adequate RV preload

188 |

R. Rajani and F.N. Kapadia |

|

|

•Morphine sulfate (2–4 mg IV) with increments of 2 mg IV should be repeated at 5–15 min for persistent chest pain unresponsive to nitroglycerine.

•Avoid nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (except aspirin) due to increased risk of mortality, reinfarction, hypertension, and heart failure, and myocardial rupture has been associated with their use.

Step 6: Give antiplatelets

•A combination of uncoated aspirin (160–325 mg orally or chewed) and clopidogrel (300–600 mg orally) should be given as a loading dose.

•This should be followed by aspirin (150 mg/day) indefinitely and clopidogrel (150 mg/day) for 7 days, then 75 mg/day for at least 1 year.

•Prasugrel (60 mg) can be used as an alternative to clopidogrel.

•Due precautions should be taken regarding complications such as known allergies and gastric intolerance.

•Proton pump inhibitors are often used concurrently to prevent gastric complications. These should be spaced out (mainly omeprazole) for 12 h after clopidogrel to prevent potential drug interaction.

•Clopidogrel may need to be withheld if the need for early surgery is anticipated in the following:

–Elderly

–Diabetics

–Known multivessel disease

–Cardiogenic shock

–Mechanical complications

Step 7: Stratify and document risk category

•The categorization of the type and extent of the myocardial infarction is primarily determined by the presence or absence of ST elevation and cardiac biomarkers of tissue injury.

•Based on this, the management should proceed for a STEMI (with or without Q waves) or non-ST elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI) (positive troponin) or unstable angina (negative troponins).

•Patients with unstable angina or NSTEMI should be risk stratified to conservative or invasive strategies (Table 23.3).

•Proper documentation of findings, ECG interpretation, medications given, and plan of action should be made in patient’s case notes (Table 23.4).

•Proper coordination among all disciplines concerned with patient care should be organized in a timely fashion.

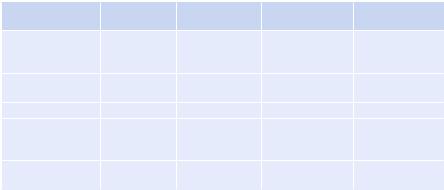

Step 8: Consider reperfusion therapy (Table 23.5)

•This can be accomplished by pharmacological (fibrinolysis) or catheter-based (primary percutaneous coronary intervention [PCI]) approaches or by emergency coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG).

23 Acute Coronary Syndromes |

189 |

|

|

Table 23.3 Selection of initial treatment strategy for patients with non-ST elevation ACS: invasive versus conservative strategy

Preferred strategy |

Patient characteristics |

Invasive |

Recurrent angina or ischemia at rest or with low-level activities despite |

|

intensive medical therapy |

|

Elevated cardiac biomarkers (TnT or TnI) |

|

New or presumably new ST-segment depression |

|

Signs or symptoms of heart failure or new or worsening mitral regurgitation |

|

High-risk findings from noninvasive testing |

|

Hemodynamic instability |

|

Sustained ventricular tachycardia |

|

PCI within 6 months |

|

Prior CABG |

|

High-risk score (e.g., TIMI [thrombolysis in myocardial infarction]) |

|

Reduced LV function (left ventricular ejection fraction [LVEF] < 40%) |

Conservative |

Low-risk score (e.g., TIMI) |

|

The patient or physician preference in absence of high-risk features |

Table 23.4 ACS: drug orders (for the initial 24 h)

Time of the onset of chest pain: |

ECG taken at: |

|

ECG diagnosis: ACS-ST elevation/non-ST elevation |

||

Is the patient a candidate for primary angioplasty (PAMI)? Y/N |

||

Drug class |

Drug |

Prescribed? (Y/N) Dose Time given Given by |

Antiplatelets |

Aspirin |

|

|

Clopidogrel |

|

Thrombolytic therapy

Contraindications to thrombolytic therapy? (Y/N)

Hemorrhagic stroke at any time, ischemic stroke within 1 year, intracranial neoplasm, active internal bleeding, suspected aortic dissection, major surgery (<3 weeks), major trauma (2–4 weeks), uncontrolled hypertension >180/110 mmHg

Heparin/low-molecular- weight heparin

Nitrates

b-blocker

ACEI

Analgesia

Statin

Laxative

Sedation

•Implementation of these strategies varies on the basis of capabilities at the treating facility and transport time to advanced facility.

190 |

R. Rajani and F.N. Kapadia |

|

|

Table 23.5 Initial documentation, choice of reperfusion strategy, and medication: assessment of reperfusion options for STEMI patients

Step 1: Assess time and risk

Time since the onset of symptoms

Risk of STEMI

Risk of fibrinolysis

Time required for transport to a skilled PCI laboratory

Step 2: Determine if fibrinolysis or invasive strategy is preferred

If presentation is <3 h and there is no delay to an invasive strategy, there is no preference for either strategy

Step 3: Fibrinolysis is generally preferred if

Early present (£3 h from symptom onset and delay to invasive strategy)

Invasive strategy is not an option

Catheterization laboratory occupied or not available:

Vascular access difficulties

Lack of access to a skilled PCI laboratory

Delay to invasive strategy

Prolonged transport

Door-to-balloon time more than 1 h

Medical contact-to-balloon or door-to-balloon more than 90 min

Step 4: An invasive strategy is generally preferred if

Skilled cardiac catheterization laboratory is available with surgical backup Medical contact-to-balloon or door-to-balloon less than 90 min

High-risk score (TIMI) Cardiogenic shock Killip class ³3

Contraindications to fibrinolysis including increased risk of bleeding and intracranial hypertension

Late presentation

Symptom onset was more than 3 h ago Diagnosis of STEMI is in doubt

Step 9: Consider primary angioplasty as the preferred mode of treatment for all suitable STEMI patients

•Coronary angioplasty with or without stent placement is the treatment of choice for the management of STEMI when it is performed effectively with a door-to- balloon time (<90 min) by a skilled provider, at a skilled PCI facility.

•Documented outcome benefits of PAMI (primary angioplasty in myocardial infarction) included a trend for a reduction of in-hospital mortality, reduction in combined end point of death or reinfarction, and intracranial hemorrhage.

•Treatment with primary angioplasty appears to reduce infarct rupture and has been associated with a significant reduction in acute mitral regurgitation, ventricular septal rupture, and a lower risk of free wall rupture.

•PAMI was also beneficial when comparing surrogate markers such as ST-segment resolution and the tissue myocardial perfusion.

23 Acute Coronary Syndromes |

|

|

191 |

|

|

|

|

||

Table 23.6 Comparison of approved fibrinolytic agents |

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

TNK-t-PA |

|

Streptokinase |

Alteplase |

Reteplase |

(tenecteplase) |

Dose |

1.5 MU in |

Up to 100 mg in |

10 U × 2 (30 min |

30–50 mg based |

|

30–60 min |

90 min (based |

apart) each over |

on weight |

|

|

on weight) |

2 min |

|

Bolus |

No |

No |

Yes |

Yes |

administration |

|

|

|

|

Antigenic |

Yes |

No |

No |

No |

Allergic reactions |

Yes |

No |

No |

No |

(hypotension most |

|

|

|

|

common) |

|

|

|

|

Systemic fibrinogen |

Marked |

Mild |

Moderate |

Minimal |

depletion |

|

|

|

|

•The degree of benefit depends on the severity of the disease, age, and delay in instituting therapy. “Door-to-balloon” time should be kept as short as possible and should be regularly audited.

•The contraindications to primary angioplasty are limited to patients who cannot receive heparin, aspirin, or thienopyridines (clopidogrel), documented lifethreatening contrast allergy, or lack of vascular access.

•High-risk patients who receive fibrinolysis in a non-PCI center should be transferred to a PCI center within 6 h of presentation to receive early PCI if indicated.

Step 10: Consider fibrinolysis in selected patients (Table 23.6)

•Fibrinolysis is restricted to patients with STEMI.

•This modality of reperfusion is best suited for patients presenting early (<3 h) and at low risk of bleeding.

•At centers without PCI facility, fibrinolysis can be given as a definitive treatment or as a bridging therapy prior to triaging to the higher center for PCI.

•STEMI patients best suited for are those presenting early after symptom onset with low bleeding risk.

•The benefit of fibrinolytic therapy appears to be greatest when agents are administered as early as possible, with best results when the drug is given less than 2 h after symptoms begin. “Door-to-needle” time should be kept as short as possible and should be regularly audited.

•Mortality reduction may still be observed in patients treated with thrombolytic agents between 6 and 12 h from the onset of ischemic symptoms, especially if there is an ongoing chest pain.

•Tenecteplase (TNK-t-PA) given as a 30–50-mg bolus is associated with the least bleeding complications and is generally seen as the preferred agent.

•The accelerated dose regimen of t-PA over 90 min produces more rapid thrombolysis than the standard 3-h infusion of t-PA.

192 |

R. Rajani and F.N. Kapadia |

|

|

•The recommended dosage regimen for t-PA is a 15-mg intravenous bolus followed by an infusion of 0.75 mg/Kg (maximum 50 mg) over 30 min, followed by an infusion of 0.5 mg/Kg (maximum 35 mg) over 60 min.

•It is associated with lower mortality and slight increase in incidence of intracranial hemorrhage but with a better overall composite outcome of death and disabling stroke.

•Contraindications for thrombolysis should be considered prior to using lytic agents (see Chap. 9).

•Intracranial hemorrhage may be fatal in half to two-thirds of patients and remains a devastating peril of thrombolytic therapy.

•In a comparative analysis, the risk of intracranial hemorrhage was found to be 1% with thrombolysis and 0.05% with PCI.

•Bleeding can also occur in sites like the gut or other sites including those of recent trauma or surgery.

•Other complications are reperfusion arrhythmias and allergic reactions.

Step 11: Consider adjunctive therapies

•Nitroglycerine

–Nitrates have a limited role in ACS.

–The indication in the setting of an ACS is limited to ongoing chest pain or ischemia, hypertension, or as a vasodilator in the management of pulmonary edema secondary to left ventricular (LV) failure.

–Route and dose of nitrate should be individualized.

–Due precaution should be taken while using nitrates (see Step 5).

•b-Blockers

–Oral b-blockers should be used within the first 24 h in those without evidence of heart failure, low cardiac output, shock, bradyarrhythmias, or conduction blocks and other conventional contraindication like asthma.

–Cardioselective agents without intrinsic sympathomimetic activity are preferred. Metoprolol (50–200 mg/day) is the most commonly used agent.

–Intravenous b-blocker is used (metoprolol 5 mg IV thrice a day) titrated to patient response, heart rate (avoid if <50/min), and blood pressure (avoid if less than 100 mmHg systolic).

–Its use is best limited to situations with ongoing chest pain or uncontrolled tachycardia or hypertension.

–Calcium channel blocking agents (diltiazem) may be used as alternative therapy in patients with contraindication to b-blockers but should be avoided in patients with poor left ventricular function and pulmonary congestion.

•Anticoagulants: Indications

–Low-molecular-weight heparins (enoxaparin 1 mg/Kg 12-hourly SC or dalteparin 120 U/Kg 12-hourly SC), or fondaparinux 2.5 mg SC once daily, are commonly used agents.

–Bivalirudin (0.1 mg/Kg bolus followed by 0.25 mg/Kg/h infusion) may be considered as an alternative agent.

–Appropriate dosing adjustments need to be done for renal dysfunction.

23 Acute Coronary Syndromes |

193 |

|

|

–As with antiplatelets, active bleeding and other contraindications need to be excluded, and the regime should be timed in consultation with cardiologist for patients requiring intervention.

–Conventional unfractionated heparin is preferable if rapid reversal prior to surgery (CABG) is anticipated.

–It should be given as a bolus of 60 U/Kg (maximum 4,000 units), then 14 U/Kg/h (maximum 1,000 U/h)—titrate to APTT 2.5 times control (see in Chap. 9).

–A weight-based nomogram may be followed for heparin titration.

–If intervention is not done, the duration for continuing anticoagulation is usually 5–10 days.

•GP IIb/IIIa inhibitors

–Abciximab 0.25 mg/Kg IV bolus and then 0.125 mcg/Kg/min (maximum 10 mcg/ min) may be given “upstream” prior to primary PCI in the catheterization laboratory.

–Eptifibatide 180 mcg/Kg bolus, then 2 mcg/Kg/min infusion or tirofiban 0.4 mcg/Kg/min for 30 min, and then 0.1 mcg/Kg/min infusion should be started as a part of early intervention strategy in high-risk patients with non-STEMI.

•Angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors and angiotensin receptor blockers

–These drugs should be used within the first 24 h of ACS in patients without hypotension.

–They are most beneficial in patients with pulmonary congestion and depressed LV systolic function.

•Statins

–The primary role of these agents is in long-term secondary prevention by lipid control.

–They may have some additional advantage in the early phase of ACS. An agent like atorvastatin is initially used in a relatively high dose (40–80 mg), and the dose can later be decreased to achieve the target lipids (LDL < 70–100 mg/dL).

–Patients who are already on statin should be continued on it.

Step 12: Manage arrhythmic complication

•Primary ventricular fibrillation (VF) accounts for the majority of early deaths during AMI. The incidence of primary VF is highest during the first 4 h after the onset of symptoms but remains an important contributor to mortality during the first 24 h.

•Secondary VF occurring in the setting of congestive heart failure or cardiogenic shock can also contribute to death from AMI.

•Prompt defibrillation and appropriate pharmacotherapy should be instituted (see Chap. 19).

•Maintain serum potassium more than 4 mEq/L and magnesium more than 2 mEq/L.

•Prophylactic antiarrhythmics are not recommended.