- •ICU Protocols

- •Preface

- •Acknowledgments

- •Contents

- •Contributors

- •1: Airway Management

- •Suggested Reading

- •2: Acute Respiratory Failure

- •Suggested Reading

- •Suggested Reading

- •Website

- •4: Basic Mechanical Ventilation

- •Suggested Reading

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •7: Weaning

- •Suggested Reading

- •8: Massive Hemoptysis

- •Suggested Reading

- •9: Pulmonary Thromboembolism

- •Suggested Reading

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •11: Ventilator-Associated Pneumonia

- •Suggested Readings

- •12: Pleural Diseases

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •13: Sleep-Disordered Breathing

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •14: Oxygen Therapy

- •Suggested Reading

- •15: Pulse Oximetry and Capnography

- •Conclusion

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •16: Hemodynamic Monitoring

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •17: Echocardiography

- •Suggested Readings

- •Websites

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •19: Cardiorespiratory Arrest

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •20: Cardiogenic Shock

- •Suggested Reading

- •21: Acute Heart Failure

- •Suggested Reading

- •22: Cardiac Arrhythmias

- •Suggested Reading

- •Website

- •23: Acute Coronary Syndromes

- •Suggested Reading

- •Website

- •Suggested Reading

- •25: Aortic Dissection

- •Suggested Reading

- •26: Cerebrovascular Accident

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •27: Subarachnoid Hemorrhage

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •28: Status Epilepticus

- •Suggested Reading

- •29: Acute Flaccid Paralysis

- •Suggested Readings

- •30: Coma

- •Suggested Reading

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •32: Acute Febrile Encephalopathy

- •Suggested Reading

- •33: Sedation and Analgesia

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •34: Brain Death

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •35: Upper Gastrointestinal Bleeding

- •Suggested Reading

- •36: Lower Gastrointestinal Bleeding

- •Suggested Reading

- •37: Acute Diarrhea

- •Suggested Reading

- •38: Acute Abdominal Distension

- •Suggested Reading

- •39: Intra-abdominal Hypertension

- •Suggested Reading

- •Website

- •40: Acute Pancreatitis

- •Suggested Reading

- •Website

- •41: Acute Liver Failure

- •Suggested Reading

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •43: Nutrition Support

- •Suggested Reading

- •44: Acute Renal Failure

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •45: Renal Replacement Therapy

- •Suggested Reading

- •Website

- •46: Managing a Patient on Dialysis

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •47: Drug Dosing

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •48: General Measures of Infection Control

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •49: Antibiotic Stewardship

- •Suggested Reading

- •Website

- •50: Septic Shock

- •Suggested Reading

- •51: Severe Tropical Infections

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •52: New-Onset Fever

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •53: Fungal Infections

- •Suggested Reading

- •Suggested Reading

- •Website

- •55: Hyponatremia

- •Suggested Reading

- •56: Hypernatremia

- •Suggested Reading

- •57: Hypokalemia and Hyperkalemia

- •57.1 Hyperkalemia

- •Suggested Reading

- •Website

- •58: Arterial Blood Gases

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •59: Diabetic Emergencies

- •59.1 Hyperglycemic Emergencies

- •59.2 Hypoglycemia

- •Suggested Reading

- •60: Glycemic Control in the ICU

- •Suggested Reading

- •61: Transfusion Practices and Complications

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •Suggested Reading

- •Website

- •63: Onco-emergencies

- •63.1 Hypercalcemia

- •63.2 ECG Changes in Hypercalcemia

- •63.3 Superior Vena Cava Syndrome

- •63.4 Malignant Spinal Cord Compression

- •Suggested Reading

- •64: General Management of Trauma

- •Suggested Reading

- •65: Severe Head and Spinal Cord Injury

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •66: Torso Trauma

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •67: Burn Management

- •Suggested Reading

- •68: General Poisoning Management

- •Suggested Reading

- •69: Syndromic Approach to Poisoning

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •70: Drug Abuse

- •Suggested Reading

- •71: Snakebite

- •Suggested Reading

- •72: Heat Stroke and Hypothermia

- •72.1 Heat Stroke

- •72.2 Hypothermia

- •Suggested Reading

- •73: Jaundice in Pregnancy

- •Suggested Reading

- •Suggested Reading

- •75: Severe Preeclampsia

- •Suggested Reading

- •76: General Issues in Perioperative Care

- •Suggested Reading

- •Web Site

- •77.1 Cardiac Surgery

- •77.2 Thoracic Surgery

- •77.3 Neurosurgery

- •Suggested Reading

- •78: Initial Assessment and Resuscitation

- •Suggested Reading

- •79: Comprehensive ICU Care

- •Suggested Reading

- •Website

- •80: Quality Control

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •81: Ethical Principles in End-of-Life Care

- •Suggested Reading

- •82: ICU Organization and Training

- •Suggested Reading

- •Website

- •83: Transportation of Critically Ill Patients

- •83.1 Intrahospital Transport

- •83.2 Interhospital Transport

- •Suggested Reading

- •84: Scoring Systems

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •85: Mechanical Ventilation

- •Suggested Reading

- •86: Acute Severe Asthma

- •Suggested Reading

- •87: Status Epilepticus

- •Suggested Reading

- •88: Severe Sepsis and Septic Shock

- •Suggested Reading

- •89: Acute Intracranial Hypertension

- •Suggested Reading

- •90: Multiorgan Failure

- •90.1 Concurrent Management of Hepatic Dysfunction

- •Suggested Readings

- •91: Central Line Placement

- •Suggested Reading

- •92: Arterial Catheterization

- •Suggested Reading

- •93: Pulmonary Artery Catheterization

- •Suggested Reading

- •Website

- •Suggested Reading

- •95: Temporary Pacemaker Insertion

- •Suggested Reading

- •96: Percutaneous Tracheostomy

- •Suggested Reading

- •97: Thoracentesis

- •Suggested Reading

- •98: Chest Tube Placement

- •Suggested Reading

- •99: Pericardiocentesis

- •Suggested Reading

- •100: Lumbar Puncture

- •Suggested Reading

- •Website

- •101: Intra-aortic Balloon Pump

- •Suggested Reading

- •Appendices

- •Appendix A

- •Appendix B

- •Common ICU Formulae

- •Appendix C

- •Appendix D: Syllabus for ICU Training

- •Index

Upper Gastrointestinal Bleeding |

35 |

|

|

Rupa Banerjee and Duvvur Nageshwar Reddy |

|

A 46-year-old male patient was brought to hospital having several episodes of vomiting of bright red blood. He had no medical history, but he had a decade-long history of excess alcohol intake, consuming 60–70 units a week.

He was pale, sweaty, and restless with a marked tremor. His pulse was 110 beats/min and blood pressure was 90/50 mmHg. He was not jaundiced, but his abdomen was distended with shifting dullness in the flanks. The liver could not be palpated, but the spleen was palpable 5 cm below the costal margin. His hemoglobin was 8.5 g/L, with platelets 45 × 109/L, bilirubin 2.5 mg/L, and creatinine 1.2.

Upper gastrointestinal (UGI) bleeding originates proximal to the ligament of Treitz, from the esophagus, stomach, and duodenum. Acute UGI bleeding is a common medical emergency, which carries a significant mortality risk. Initial triage, assessment, and prompt action can save lives.

Step 1: Initiate resusc itation and assessment of hemodynamic stability

•The first step in the management of such a patient is initial clinical assessment of the hemodynamic instability and the requirement for immediate resuscitation. Initial resuscitation is done as mentioned in Chap. 78.

•Patients who present with hemodynamic instability and significant hematemesis will have resting tachycardia (pulse ³100 per min), hypotension (systolic blood

R. Banerjee, M.D., D.T.M. (*) • D.N. Reddy, D.M., F.R.C.P.

Department of Gastroenterology, Asian Institute of Gastroenterology, Hyderabad, India e-mail: dr_rupa_banerjee@hotmail.com

R. Chawla and S. Todi (eds.), ICU Protocols: A stepwise approach, |

285 |

DOI 10.1007/978-81-322-0535-7_35, © Springer India 2012 |

|

286 |

R. Banerjee and D.N. Reddy |

|

|

Table 35.1 Clinical features of significant upper GI bleeding

•Shock

•Orthostatic hypotension

•Profuse active bleeding

•Decrease in HCT ³10%

•Anticipated transfusion >2 units of RBCs

pressure <100 mmHg), or postural changes (increase in the pulse of ³20 beats/ min or a drop in systolic blood pressure of ³20 mmHg on standing) (Table 35.1).

•In patients with exsanguinating bleeding or the patient who is delirious, airway should be protected by elective intubation. In conscious patients, give oxygen by nasal cannula.

•Two large-bore intravenous channels should be placed at the earliest.

•Fluid resuscitation should be started with Ringer’s lactate or normal saline. Crystalloid or colloid solutions may be used for treating hypotension aiming a systolic blood pressure of more than 100 mmHg.

•Do typing and crossmatching of blood. Target hemoglobin usually around 7–8 g% for otherwise healthy individuals without active bleeding. A target hemoglobin concentration of about 9 g% would be appropriate in patients older than 65 years or those with cardiovascular disease.

•The patient should be kept nil orally. This is necessary because an urgent endoscopy or even intubation may be needed in the event of a repeat bleeding.

•Stop factors that enhance bleeding—anticoagulants (warfarin, heparin) and antiplatelet agents (aspirin, clopidogrel).

Step 2: Find etiology and stratify risk

•The severity of presenting symptoms, current medications, and history are instrumental in establishing the etiology of UGI bleeding.

•The history of use of aspirin and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) suggests a bleeding ulcer. The history of prolonged alcohol intake and the stigmata of chronic liver disease including jaundice and ascites would indicate a possible variceal hemorrhage.

•Hematemesis that follows prolonged vomiting or retching may be suggestive of a Mallory–Weiss tear. Bright red blood vomit in large amounts is usually suggestive of severe hemorrhage from an arterial or variceal source.

•The presence of the characteristic coffee-ground vomitus implies that bleeding has ceased or has been relatively modest.

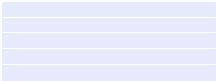

•The common causes of UGI bleeding are shown in Table 35.2. Patients are usually stratified into variceal or nonvariceal hemorrhage as the treatment algorithms and prognosis differ accordingly.

•Majority (~80%) of acute episodes of UGI bleeding have been attributed to peptic ulcer disease.

•Peptic ulcer bleeding is predominant in the elderly, with 70% of patients older than 60 years.

•Majority of episodes are related to the use of aspirin and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.

35 Upper Gastrointestinal Bleeding |

|

287 |

|

|

|

Table 35.2 Common causes |

• |

Peptic ulcer disease |

of UGI hemorrhage |

• Gastric erosions and ulcers (drug induced) |

|

|

||

|

• Esophageal or gastric varices (variceal bleeding) |

|

|

• |

Esophageal ulcers/esophagitis |

|

• |

Mallory–Weiss tear |

|

• |

Malignancy |

|

• Angiodysplasia and vascular malformations |

|

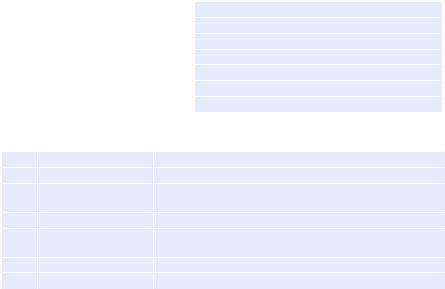

Table 35.3 Factors associated with a poor outcome in UGI bleeding

1. |

Age |

Mortality increases with age among all age groups |

2. |

Comorbidity |

No comorbidity: low mortality; any comorbidity doubles risk |

3. |

Liver disease |

Cirrhosis increases mortality rate; mortality due to variceal |

|

|

bleeding up to 14% |

4. |

Initial shock |

Increased mortality and need for intervention |

5. |

Continued bleeding |

Postadmission continued bleeding: ↑ intervention, almost |

|

|

5 times ↑ mortality |

6. |

Hematemesis |

Presence of initial hematemesis doubles mortality |

7. |

High urea |

Poor outcome; increased need for intervention |

NSAIDs and anticoagulants do not adversely affect clinical outcome of UGI bleeding

•The annual incidence of bleeding from peptic ulcer has shown a decline, but the mortality rate remains high at approximately 6–8%.

•Variceal bleeding is related directly to portal hypertension, and cirrhosis is the commonest etiology. The mortality rate for variceal bleeding is high at 30–40%, with a 70% risk of rebleeding in a year.

Risk stratification

•Patients with hematemesis need to be stratified according to the risk of poor outcome including uncontrolled bleeding, rebleeding, need for intervention, and mortality.

•These factors should be taken into account when determining the need for ICU admission or suitability for discharge.

The factors associated with a poor outcome are shown in Table 35.3.

Simple and widely validated scoring systems are needed to identify patients at

high risk of rebleeding, death, and active intervention for optimum management. Modified Glasgow–Blatchford bleeding score and the Rockall score are the two common scores used for risk stratification. Modified Glasgow–Blatchford bleeding score is a good tool, and it helps to decide the need for endoscopy.

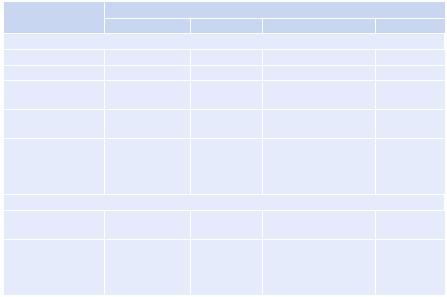

•The Rockall score is the sum of each component, calculated before and after endoscopy (Table 35.4). This predicts rates of rebleeding and mortality and can be used in management algorithms.

•The full Rockall score comprises the initial score as well as additional points for endoscopic diagnosis (0–2 points), and endoscopic stigmata of recent hemorrhage (0–2 points) giving a maximum score of 11 points.

288 |

|

|

R. Banerjee and D.N. Reddy |

|

|

|

|||

Table 35.4 The Rockall score for prognostication of UGI bleeding |

|

|||

|

Score |

|

|

|

|

0 |

1 |

2 |

3 |

Preendoscopy |

|

|

|

|

Age (years) |

<60 |

60–79 |

>80 |

|

Shock |

|

|

|

|

Blood pressure |

>100 |

>100 |

<100 |

|

(mmHg) |

|

|

|

|

Heart rate |

<100 |

>100 |

>100 |

|

(per minute) |

|

|

|

|

Comorbidity |

None |

|

Heart failure, ischemic |

Renal/liver |

|

|

|

heart disease, and any |

failure, |

|

|

|

major comorbidity |

disseminated |

|

|

|

|

malignancy |

Postendoscopy |

|

|

|

|

Diagnoses |

Mallory–Weiss/ |

All other |

Gastrointestinal |

|

|

no lesion found |

malignancy |

malignancy |

|

Major stigmata of |

None/dark spot |

|

Bleeding in UGI tract, |

|

bleeding |

only |

|

nonbleeding visible |

|

|

|

|

vessels, spurting |

|

|

|

|

vessels, adherent clot |

|

•Postendoscopy risk scores of more than 2 are associated with a 4% risk of rebleeding and 0.1% mortality. Overall, patients with a score of 0, 1, and 2 have a lower risk of hemorrhage, whereas approximately 80% of patients with a postendoscopy score of 8 or more will rebleed. Accordingly, significant health savings could be achieved by early endoscopy and discharge of patients with low scores.

Step 3: Send investigations

•Hemoglobin levels are required in all patients. It must however be noted that initial levels may be falsely high and underestimate true blood loss due to hemoconcentration.

•Blood should be sent urgently for crossmatching and availability.

•Send blood parameters including prothrombin time, partial thromboplastin time, and platelet count.

•Blood urea, creatinine, and liver function tests may assist in diagnosing the cause and severity of bleeding.

•Baseline ECG.

Step 4: Further treatment

•Any coagulopathy found needs to be corrected by appropriate blood products. If prothrombin time/international normalized ratio is prolonged, give fresh frozen plasma or vitamin K injection.

•Proton-pump inhibitors: 80 mg IV bolus should be administered followed by intravenous infusion of 8 mg/h or 40 mg 12 hourly.

35 Upper Gastrointestinal Bleeding |

289 |

|

|

•If there is known or suspected variceal bleeding (or known or suspected chronic liver disease), empiric treatment with terlipressin 2 mg IV stat followed by 2 mg IV QDS and a dose of broad-spectrum antibiotics should be given.

•If there is history of active alcohol abuse, thiamine replacement should be started.

Step 5: Insert the nasogastric tube

•The nasogastric tube insertion is helpful in many ways. The type of aspirate such as fresh blood, bilious, or altered blood helps in determining whether bleeding is ongoing or has stopped.

•Gastric lavage before endoscopy also helps in giving a clear view for endoscopy.

•It may be avoided in uncooperative and delirious patients or in the patient who is retching as it may precipitate further bleeding.

Step 6: Carry out endoscopy

•Endoscopy is a mainstay for all cases of UGI bleeding. It enables:

–Identification of the source of bleeding

–Therapeutic intervention to achieve hemostasis if required

•UGI barium studies are contraindicated as they interfere with subsequent endoscopy or surgery. Also, the yield is very poor.

•Timing of endoscopy: After resuscitation, an endoscopy is arranged. Patients with profuse hemorrhage may need emergency endoscopy; the endoscopy should take place within 24 h of presentation, both to guide management and to facilitate the early discharge of patients with a low risk of recurrent bleeding.

•In nonvariceal bleeding, the endoscopic risk factors for rebleeding are to be identified, as they help in deciding when to offer endoscopic therapy.

Step 7: Specific treatment

•Cases of 80% of UGI bleeding stop spontaneously. Mortality is approximately 10%.

•The endoscopic therapy for bleeding is summarized in Fig. 35.1. A. For nonvariceal bleeding

•Intravenous proton-pump inhibitor bolus is followed by infusion for 72 h after endoscopic hemostasis; oral proton-pump inhibitors can be started after completion of intravenous therapy.

•Stop NSAIDs and substitute with less toxic drugs.

•There is no role for H2 blocker, somatostatin, or octreotide.

•Oral intake of clear liquids can be initiated 6 h after endoscopy in patients with hemodynamic stability.

•Helicobacter pylorus testing is required, and appropriate treatment should be started if the result is positive.

•Surgical or interventional radiologic consultation should be taken for angiography for selected patients with failure of endoscopic hemostasis or massive rebleeding.