- •ICU Protocols

- •Preface

- •Acknowledgments

- •Contents

- •Contributors

- •1: Airway Management

- •Suggested Reading

- •2: Acute Respiratory Failure

- •Suggested Reading

- •Suggested Reading

- •Website

- •4: Basic Mechanical Ventilation

- •Suggested Reading

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •7: Weaning

- •Suggested Reading

- •8: Massive Hemoptysis

- •Suggested Reading

- •9: Pulmonary Thromboembolism

- •Suggested Reading

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •11: Ventilator-Associated Pneumonia

- •Suggested Readings

- •12: Pleural Diseases

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •13: Sleep-Disordered Breathing

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •14: Oxygen Therapy

- •Suggested Reading

- •15: Pulse Oximetry and Capnography

- •Conclusion

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •16: Hemodynamic Monitoring

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •17: Echocardiography

- •Suggested Readings

- •Websites

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •19: Cardiorespiratory Arrest

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •20: Cardiogenic Shock

- •Suggested Reading

- •21: Acute Heart Failure

- •Suggested Reading

- •22: Cardiac Arrhythmias

- •Suggested Reading

- •Website

- •23: Acute Coronary Syndromes

- •Suggested Reading

- •Website

- •Suggested Reading

- •25: Aortic Dissection

- •Suggested Reading

- •26: Cerebrovascular Accident

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •27: Subarachnoid Hemorrhage

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •28: Status Epilepticus

- •Suggested Reading

- •29: Acute Flaccid Paralysis

- •Suggested Readings

- •30: Coma

- •Suggested Reading

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •32: Acute Febrile Encephalopathy

- •Suggested Reading

- •33: Sedation and Analgesia

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •34: Brain Death

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •35: Upper Gastrointestinal Bleeding

- •Suggested Reading

- •36: Lower Gastrointestinal Bleeding

- •Suggested Reading

- •37: Acute Diarrhea

- •Suggested Reading

- •38: Acute Abdominal Distension

- •Suggested Reading

- •39: Intra-abdominal Hypertension

- •Suggested Reading

- •Website

- •40: Acute Pancreatitis

- •Suggested Reading

- •Website

- •41: Acute Liver Failure

- •Suggested Reading

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •43: Nutrition Support

- •Suggested Reading

- •44: Acute Renal Failure

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •45: Renal Replacement Therapy

- •Suggested Reading

- •Website

- •46: Managing a Patient on Dialysis

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •47: Drug Dosing

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •48: General Measures of Infection Control

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •49: Antibiotic Stewardship

- •Suggested Reading

- •Website

- •50: Septic Shock

- •Suggested Reading

- •51: Severe Tropical Infections

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •52: New-Onset Fever

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •53: Fungal Infections

- •Suggested Reading

- •Suggested Reading

- •Website

- •55: Hyponatremia

- •Suggested Reading

- •56: Hypernatremia

- •Suggested Reading

- •57: Hypokalemia and Hyperkalemia

- •57.1 Hyperkalemia

- •Suggested Reading

- •Website

- •58: Arterial Blood Gases

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •59: Diabetic Emergencies

- •59.1 Hyperglycemic Emergencies

- •59.2 Hypoglycemia

- •Suggested Reading

- •60: Glycemic Control in the ICU

- •Suggested Reading

- •61: Transfusion Practices and Complications

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •Suggested Reading

- •Website

- •63: Onco-emergencies

- •63.1 Hypercalcemia

- •63.2 ECG Changes in Hypercalcemia

- •63.3 Superior Vena Cava Syndrome

- •63.4 Malignant Spinal Cord Compression

- •Suggested Reading

- •64: General Management of Trauma

- •Suggested Reading

- •65: Severe Head and Spinal Cord Injury

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •66: Torso Trauma

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •67: Burn Management

- •Suggested Reading

- •68: General Poisoning Management

- •Suggested Reading

- •69: Syndromic Approach to Poisoning

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •70: Drug Abuse

- •Suggested Reading

- •71: Snakebite

- •Suggested Reading

- •72: Heat Stroke and Hypothermia

- •72.1 Heat Stroke

- •72.2 Hypothermia

- •Suggested Reading

- •73: Jaundice in Pregnancy

- •Suggested Reading

- •Suggested Reading

- •75: Severe Preeclampsia

- •Suggested Reading

- •76: General Issues in Perioperative Care

- •Suggested Reading

- •Web Site

- •77.1 Cardiac Surgery

- •77.2 Thoracic Surgery

- •77.3 Neurosurgery

- •Suggested Reading

- •78: Initial Assessment and Resuscitation

- •Suggested Reading

- •79: Comprehensive ICU Care

- •Suggested Reading

- •Website

- •80: Quality Control

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •81: Ethical Principles in End-of-Life Care

- •Suggested Reading

- •82: ICU Organization and Training

- •Suggested Reading

- •Website

- •83: Transportation of Critically Ill Patients

- •83.1 Intrahospital Transport

- •83.2 Interhospital Transport

- •Suggested Reading

- •84: Scoring Systems

- •Suggested Reading

- •Websites

- •85: Mechanical Ventilation

- •Suggested Reading

- •86: Acute Severe Asthma

- •Suggested Reading

- •87: Status Epilepticus

- •Suggested Reading

- •88: Severe Sepsis and Septic Shock

- •Suggested Reading

- •89: Acute Intracranial Hypertension

- •Suggested Reading

- •90: Multiorgan Failure

- •90.1 Concurrent Management of Hepatic Dysfunction

- •Suggested Readings

- •91: Central Line Placement

- •Suggested Reading

- •92: Arterial Catheterization

- •Suggested Reading

- •93: Pulmonary Artery Catheterization

- •Suggested Reading

- •Website

- •Suggested Reading

- •95: Temporary Pacemaker Insertion

- •Suggested Reading

- •96: Percutaneous Tracheostomy

- •Suggested Reading

- •97: Thoracentesis

- •Suggested Reading

- •98: Chest Tube Placement

- •Suggested Reading

- •99: Pericardiocentesis

- •Suggested Reading

- •100: Lumbar Puncture

- •Suggested Reading

- •Website

- •101: Intra-aortic Balloon Pump

- •Suggested Reading

- •Appendices

- •Appendix A

- •Appendix B

- •Common ICU Formulae

- •Appendix C

- •Appendix D: Syllabus for ICU Training

- •Index

Acute Liver Failure |

41 |

|

|

Shalimar and Subrat Kumar Acharya |

|

A 25-year-old male patient presented with recent-onset fever and jaundice, followed by altered sensorium. He had bradycardia, HR 50/min, icterus, and bilateral equal pupils reacting to light. Liver span was one intercostal space without splenomegaly. He was unconscious, responding only to painful stimuli. Liver function tests showed total bilirubin of 15 mg/dL, with conjugated fraction of 10 mg/dL, and aspartate transaminase, alanine transaminase, and alkaline phosphatase were 2,500, 3,000, and 450 IU, respectively. Prothrombin time was more than 1 min over the control. Platelet counts were normal. IgM hepatitis E virus (HEV) antibodies were positive.

The life of an individual is endangered in acute liver failure (ALF) as a consequence of multiple metabolic and hemodynamic disturbances resulting from severe acute liver injury. This disease carries high morbidity and mortality in the absence of hepatic transplantation.

Step 1: Initiate resuscitation

•Ensure the maintenance of airway, breathing, and circulation as in any critical illness, as described in Chap. 78.

•Extra precaution needs to be taken while intubating these patients to avoid sudden increase of intracranial pressure (ICP) and herniation.

•Proper sedation, anti-edema measures, and experienced personnel are prerequisites for intubation.

Shalimar, M.D., D.M. (*) • S.K. Acharya, M.D.

Department of Gastroenterology, All India Institute of Medical Sciences, New Delhi, India

e-mail: drshalimar@yahoo.com

R. Chawla and S. Todi (eds.), ICU Protocols: A stepwise approach, |

327 |

DOI 10.1007/978-81-322-0535-7_41, © Springer India 2012 |

|

328 |

Shalimar and S.K. Acharya |

|

|

Table 41.1 Causes of FHF |

Broad categories |

|

Infections |

|

Metabolic diseases |

|

Drugs |

|

Toxins |

|

ALF of pregnancy |

|

Autoimmune hepatitis |

|

Acute Budd–Chiari syndrome |

|

Shock liver |

|

Individual etiological agents |

|

Hepatotropic viruses (A to E) |

|

Cytomegalovirus, herpes simplex virus |

|

Wilson’s disease, galactosemia |

|

Paracetamol, isoniazid, rifampicin, sodium valproate |

|

Amanita phalloides |

Step 2: Identify ALF and its causes

•In a clinical setting, hepatic injury is usually recognized by appearance of jaundice, and liver failure is recognized by occurrence of encephalopathy, ascites, and coagulopathy.

•Proper history should be taken regarding medications, rash, needlestick injury, blood transfusion, previous surgery, and history of jaundice in family members, to identify the cause of fulminant hepatic failure (FHF) (Table 41.1).

•Other causes of fever with encephalopathy such as bacterial sepsis and tropical infections in endemic areas such as malaria, enteric fever, leptospira, dengue, meningitis, encephalitis, cholangitis, and underlying chronic liver disease should be ruled out. While initial supportive therapy is being given, diagnostic workup should be

sent. These include the following:

•Complete blood count, blood glucose, blood urea nitrogen, creatinine, electrolytes, liver function tests, and prothrombin time

•Arterial blood gases, arterial ammonia and lactate

•Chest X-ray, ECG

•Endotracheal aspirate for aerobic culture in intubated patients, blood culture and urine culture

•Serology including HBsAg, IgM anti-HBc, IgM anti-HEV, IgM anti-HAV, antiHCV, anti-HDV, and anti-HIV

•Copper studies, autoimmune markers

•Bedside ultrasound

Step 3: Assess prognosis

The assessment of the grade of encephalopathy and prognostic indicators should be done, as described in Tables 41.2 and 41.3. Patients who develop ALF within 7–10 days of the onset of icterus have significantly higher survival rates than those who develop encephalopathy later. However, this is not a universal finding.

41 Acute Liver Failure |

329 |

|

|

|

|

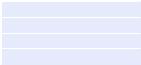

Table 41.2 Clinical stages of hepatic encephalopathy |

|

|

Stage |

Mental status |

Neuromuscular function |

1 |

Impaired attention, irritability, depression |

Tremor, incoordination, apraxia |

2 |

Drowsiness, behavioral changes, memory |

Asterixis, slowed or slurred speech, |

|

impairment, sleep disturbances |

ataxia |

3 |

Confusion, disorientation, somnolence, |

Hypoactive reflexes, nystagmus, clonus, |

|

amnesia |

muscular rigidity |

4 |

Stupor and coma |

Dilated pupils and decerebrate |

|

|

posturing, oculocephalic reflex |

Table 41.3 Prognostic criteria in ALF predicting high mortality: King’s College and other criteria

Nonparacetamol |

Paracetamol |

|

Prothrombin time (PT) >100 s or |

Plasma pH < 7.30 or |

|

Any three of the following: |

Arterial lactate level >3.5 mmol/L at 4 h or |

|

(a) |

Age <10 or >40 years |

Arterial lactate level >3.0 mmol/L at 12 h |

(b) |

Etiology—non-A, non-B hepatitis |

Or |

(c) |

Drug-induced hepatitis |

PT > 100 s (INR >6.5) and serum creatinine |

(d) |

Icterus–encephalopathy interval >7 days |

>3.4 mg/dL in patients with grade 3–4 |

(e) |

PT > 50 s (INR > 3.5) |

encephalopathy |

|

||

(f) |

Serum bilirubin > 17.5 mg/dL |

|

Clichy criteria (France):

(a)Factor V levels <20% of normal in patients <30 years of age

(b)Factor V levels <30% of normal in patients >30 years of age

Prognostic markers in Indian patients with ALF:

1.Age ³40 years

2.Cerebral edema at admission

3.Serum bilirubin ³15 mg/dL

4.PT ³ 25 s than normal

Presence of ³3 of these factors—90% mortality

Step 4: Early referral for liver transplant

•If orthotopic liver transplant (OLT) is available, early referral of such patients who have adverse prognostic factors to the transplant center is recommended.

•If the patient is in the transplant center, he or she should be on the transplant list and workup for that should start before the development of advanced encephalopathy or other complications of liver failure develop, which are usually fatal (Table 41.4).

•A balanced view regarding chances of spontaneous recovery with supportive measures, contraindications for transplantation, resources available, and cost consideration needs to be taken judiciously by a multidisciplinary team in each case.

•Prognostic models such as King’s College criteria and Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Examination (APACHE) II are helpful in this regard. An APACHE II of more than 15 is associated with increased need for transplantation.

330 |

Shalimar and S.K. Acharya |

|

|

Table 41.4 Causes of death |

Cerebral edema |

|

Sepsis |

|

Renal failure |

|

Gastrointestinal bleeding |

Step 5: General supportive measures

•Correct fluid status and avoid hypoor hypervolemia.

•Strict aseptic precautions should be practiced while handling catheter and tubes.

•Administer supplemental oxygen in case of hypoxemia and avoid hypercapnia.

•Avoid hypertension/hypotension.

•Manage fever with surface cooling.

•Neck should be kept in neutral position.

•Minimize external stimuli.

•Monitor blood glucose 2 hourly and maintain between 140 and 180 mg%.

•Monitor serum electrolytes and correct it.

•Nutrition—nasogastric feeding should be started early with gradual increase in protein supplementation.

•Strict aseptic precautions should be followed while handling the lines and catheters.

Step 6: Manage specific problems

(a)Cerebral edema and increased ICP

•Raise head end 30–45°.

•Avoid unnecessary stimulation and movement of the patient—it may induce overt features of cerebral edema.

•Identification of elevated ICP and its management is important because cerebral edema resulting in brainstem herniation is the commonest cause of death among patients with ALF (Table 41.5). Usual recommendation is to keep the ICP below 15 mmHg; however, it is probably more important to maintain the cerebral perfusion pressure (mean arterial pressure minus intracranial pressure) above 50 mmHg.

•The placement of intracranial transducers is usually avoided in patients with ALF as it may be associated with life-threatening bleeding and sepsis. Further, such interventions do not improve survival, so it is not practiced widely.

(b)Sepsis is the second major cause of death among ALF.

•Gram-negative bacteria are the major cause of sepsis in these patients.

•Prophylactic parenteral antibiotics using third-generation cephalosporins may reduce the incidence of sepsis.

•Fungal infection is also common in this population. Prophylactic fluconazole, in selected cases with multiple-site colonization with yeast, may be used.

•Surveillance cultures should be sent, and high index of suspicion and low threshold for starting broad-spectrum antibiotics should be practiced.

(c)Renal failure: Both intermittent hemodialysis and continuous renal replacement therapy (CRRT) are equally effective, with later more suitable for unstable patients as it avoids fluctuation in ICP.

41 Acute Liver Failure |

331 |

|

|

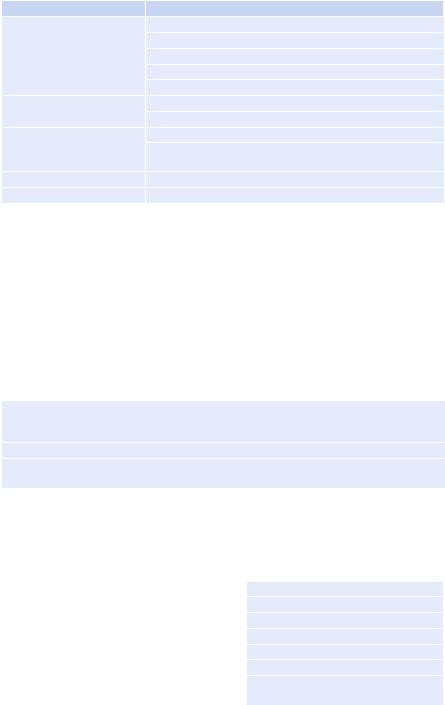

Table 41.5 Cerebral edema and raised ICP |

|

Symptoms/signs |

Management |

Hyperventilation |

Elevate the head and the trunk 35–40° |

|

Avoid vigorous endotracheal suction |

|

Avoid hyperthermia |

|

Remove constricting tapes |

|

Sedate the patient |

Bradycardia |

100 mL mannitol (20%) stat followed by 1 g/kg q8 hourly |

|

Hypertonic saline |

Focal seizures |

Elective intubation in grades 3–4 encephalopathy |

|

Hyperventilation (target PaCO2 30–32 mmHg) and hypothermia |

|

in selected cases |

Decerebrate postures |

|

Absent pupillary reflexes |

|

(d)Coagulopathy: Prophylactic use of fresh frozen plasma (FFP) is not helpful unless a planned procedure is followed. Once bleeding occurs, only then FFP and platelet transfusion should be given. FFP can precipitate volume overload in these patients, and in selected cases, off-label use of recombinant factor VII may be considered.

(e)Seizures: Prophylactic therapy with phenytoin is not useful. Levetiracetam may be used for the treatment as it does not have hepatotoxicity.

Step 7: Manage specific situation

(a)Paracetamol overdose—N-acetyl cysteine (NAC): 150 mg/kg over 1 h, followed by

12.5 mg/kg/h for 4 h and then 6.25 mg/kg/h for 67 h. NAC has been found to be useful in both acetaminophen and non-acetaminophen-induced ALF.

(b)Special situation—pregnancy

– Pregnant women who develop acute viral hepatitis are more likely to develop ALF than nonpregnant women.

Step 8: Remember that many therapies have doubtful role in the management of ALF and should not be used (Table 41.6)

Table 41.6 Therapies not |

Lactulose |

useful in ALF |

L-Ornithine L-aspartate |

|

|

|

Branched-chain amino acids |

|

FFP transfusion in absence of bleeding |

|

Prophylactic phenytoin |

|

Enteral decontamination |

|

Prophylactic hyperventilation for raised |

|

intracranial hypertension |