Borchers Andrea Ann (ed.) Handbook of Signs & Symptoms 2015

.pdf

Ask the patient to describe a typical day’s diet; estimate his daily fiber and fluid intake. Ask him about changes in eating habits, medication or alcohol use, or physical activity. Has he experienced recent emotional distress? Has constipation affected his family life or social contacts? Also, ask about his job and exercise pattern. A sedentary or stressful job can contribute to constipation.

Find out whether the patient has a history of GI, rectoanal, neurologic, or metabolic disorders; abdominal surgery; or radiation therapy. Then, ask about the medications he’s taking, including opioids and over-the-counter preparations, such as laxatives, mineral oil, stool softeners, and enemas.

Inspect the abdomen for distention or scars from previous surgery. Then, auscultate for bowel sounds, and characterize their motility. Percuss all four quadrants, and gently palpate for abdominal tenderness, a palpable mass, and hepatomegaly. Next, examine the patient’s rectum. Spread his buttocks to expose the anus, and inspect for inflammation, lesions, scars, fissures, and external hemorrhoids. Use a disposable glove and lubricant to palpate the anal sphincter for laxity or stricture. Also, palpate for rectal masses and fecal impaction. Finally, obtain a stool sample and test it for occult blood.

As you assess the patient, remember that constipation can result from several life-threatening

disorders, such as an acute intestinal obstruction and mesenteric artery ischemia, but it doesn’t herald these conditions.

Medical Causes

Anal fissure. A crack or laceration in the lining of the anal wall can cause acute constipation, usually due to the patient’s fear of the severe tearing or burning pain associated with bowel movements. He may notice a few drops of blood streaking toilet tissue or his underwear.

Anorectal abscess. In anorectal abscess, constipation occurs together with severe, throbbing, localized pain and tenderness at the abscess site. The patient may also have localized inflammation, swelling, and purulent drainage and may complain of fever and malaise.

Cirrhosis. In the early stages of cirrhosis, the patient experiences constipation along with nausea and vomiting and a dull pain in the right upper quadrant. Other early findings include indigestion, anorexia, fatigue, malaise, flatulence, hepatomegaly and, possibly, splenomegaly and diarrhea.

Diabetic neuropathy. Diabetic neuropathy produces episodic constipation or diarrhea. Other signs and symptoms include dysphagia, orthostatic hypotension, syncope, and painless bladder distention with overflow incontinence. A male patient may also experience erectile dysfunction and retrograde ejaculation.

Diverticulitis. In diverticulitis, constipation or diarrhea occurs with left lower quadrant pain and tenderness and possibly a palpable, tender, firm, fixed abdominal mass. The patient may develop mild nausea, flatulence, or a low-grade fever.

Hemorrhoids. Thrombosed hemorrhoids cause constipation as the patient tries to avoid the severe pain of defecation. The hemorrhoids may bleed during defecation.

Hepatic porphyria. Abdominal pain, which may be severe, precedes constipation in hepatic porphyria, a rare genetic disorder that affects the production of heme. The patient may also experience nausea; vomiting; muscle weakness; pain in the back, arms, and legs; red urine; palpitations; hallucinations; and seizures.

Hypercalcemia. With hypercalcemia, constipation usually occurs along with anorexia, nausea, vomiting, polyuria, and polydipsia. The patient may also display arrhythmias, bone pain, muscle weakness and atrophy, hypoactive deep tendon reflexes, and personality changes.

Hypothyroidism. Constipation occurs early and insidiously in patients with hypothyroidism, in addition to fatigue, sensitivity to cold, anorexia with weight gain, menorrhagia in women, decreased memory, hearing impairment, muscle cramps, and paresthesia.

Intestinal obstruction. Constipation associated with an intestinal obstruction varies in severity and onset, depending on the location and extent of the obstruction. With partial obstruction, constipation may alternate with leakage of liquid stools. With complete obstruction, obstipation may occur. Constipation can be the earliest sign of partial colon obstruction, but it usually occurs later if the level of the obstruction is more proximal. Associated findings include episodes of colicky abdominal pain, abdominal distention, nausea, or vomiting. The patient may also develop hyperactive bowel sounds, visible peristaltic waves, a palpable abdominal mass, and abdominal tenderness.

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS). IBS commonly produces recurring constipation, although some patients have intermittent, watery diarrhea and others complain of alternating constipation and diarrhea. Stress and certain foods may trigger nausea and abdominal distention and tenderness, but defecation usually relieves these signs and symptoms. Patients typically have an

intense urge to defecate and feelings of incomplete evacuation. Typically, the stools are scybalous and contain visible mucus.

Mesenteric artery ischemia. Mesenteric artery ischemia is a life-threatening disorder that produces sudden constipation with failure to expel stool or flatus. Initially, the abdomen is soft and nontender, but soon severe abdominal pain, tenderness, vomiting, and anorexia occur. Later, the patient may develop abdominal guarding, rigidity, and distention; tachycardia; syncope; tachypnea; a fever; and signs of shock, such as cool, clammy skin and hypotension. A bruit may be heard.

Spinal cord lesion. Constipation may occur with a spinal cord lesion, in addition to urine retention, sexual dysfunction, pain, and, possibly, motor weakness, paralysis, or sensory impairment below the level of the lesion.

Other Causes

Diagnostic tests. Constipation can result from the retention of barium given during certain GI studies.

Drugs. Patients commonly experience constipation when taking an opioid analgesic or other drugs, including Vinca alkaloids, calcium channel blockers, antacids containing aluminum or calcium, anticholinergics, and drugs with anticholinergic effects (such as tricyclic antidepressants). Patients may also experience constipation from excessive use of laxatives or enemas.

Surgery and radiation therapy. Constipation can result from rectoanal surgery, which may traumatize nerves, and abdominal irradiation, which may cause intestinal stricture.

Special Considerations

As indicated, prepare the patient for diagnostic tests, such as proctosigmoidoscopy, colonoscopy, barium enema, plain abdominal films, and an upper GI series. If the patient is on bed rest, reposition him frequently, and help him perform active or passive exercises, as indicated. Teach abdominal toning exercises if the patient’s abdominal muscles are weak and relaxation techniques to help him reduce stress related to constipation.

Patient Counseling

Encourage avoidance of straining, laxatives, and enemas. Explain the role of diet and fluid intake. Discuss and encourage the patient to exercise and, in particular, to perform abdominal toning exercises. Train him in relaxation techniques.

Pediatric Pointers

The high content of casein and calcium in cow’s milk can produce hard stools and possible constipation in bottle-fed infants. Other causes of constipation in infants include inadequate fluid intake, Hirschsprung’s disease, and anal fissures. In older children, constipation usually results from inadequate fiber intake and excessive intake of milk; it can also result from bowel spasm, mechanical obstruction, hypothyroidism, a reluctance to stop playing for bathroom breaks, and the lack of privacy in some school bathrooms.

Geriatric Pointers

Acute constipation in elderly patients is usually associated with underlying structural abnormalities. Chronic constipation, however, is chiefly caused by lifelong bowel and dietary habits and laxative use.

REFERENCES

Savica, R., Rocca, W., & Ahlskog, E. (2010) . When does Parkinson disease start? Journal of the American Medical Association, 67(7), 798–801.

Sung, H. Y. , Choi, M. G., Lee, K. S., & Kim, J. S. (2012) . Anorectal manometric dysfunctions in newly diagnosed, early-state Parkinson’s disease. Journal of Clinical Neurology, 8(3), 184–189.

Corneal Reflex, Absent

The corneal reflex is tested by drawing a fine-pointed wisp of sterile cotton from a corner of each eye to the cornea. Normally, even though only one eye is tested at a time, the patient blinks bilaterally each time either cornea is touched — this is the corneal reflex. When this reflex is absent, neither eyelid closes when the cornea of one is touched. (See Eliciting the Corneal Reflex.)

The site of the afferent fibers for this reflex is in the ophthalmic branch of the trigeminal nerve (cranial nerve [CN] V); the efferent fibers are located in the facial nerve (CN VII). Absence of the corneal reflex may result from damage to these nerves.

History and Physical Examination

If you can’t elicit the corneal reflex, look for other signs of trigeminal nerve dysfunction. To test the three sensory portions of the nerve, touch each side of the patient’s face on the brow, cheek, and jaw with a cotton wisp, and ask him to compare the sensations.

EXAMINATION TIP Eliciting the Corneal Reflex

EXAMINATION TIP Eliciting the Corneal Reflex

To elicit the corneal reflex, have the patient turn his eyes away from you to avoid involuntary blinking during the procedure. Then, approach the patient from the opposite side, out of his line of vision, and brush the cornea lightly with a fine wisp of sterile cotton. Repeat the procedure on the other eye.

If you suspect facial nerve involvement, note if the upper face (brow and eyes) and lower face (cheek, mouth, and chin) are weak bilaterally. Lower motor neuron facial weakness affects the face on the same side as the lesion, whereas upper motor neuron weakness affects the side opposite the lesion — predominantly the lower facial muscles.

Because an absent corneal reflex may signify such progressive neurologic disorders as GuillainBarré syndrome, ask the patient about associated symptoms — facial pain, dysphagia, and limb weakness.

Medical Causes

Acoustic neuroma. Acoustic neuroma affects the trigeminal nerve, causing a diminished or absent corneal reflex, tinnitus, and unilateral hearing impairment. Facial palsy and anesthesia, palate weakness, and signs of cerebellar dysfunction (ataxia, nystagmus) may result if the tumor impinges on the adjacent cranial nerves, brain stem, and cerebellum.

Bell’s palsy. A common cause of diminished or absent corneal reflex, Bell’s palsy causes paralysis of CN VII. It can also produce complete hemifacial weakness or paralysis and drooling on the affected side, which also sags and appears masklike. The eyelid on the affected side won’t close completely, and the eye tears constantly.

Brain stem infarction or injury. An absent corneal reflex can occur on the side opposite the lesion when infarction or injury affects CN V or VII or their connection in the central trigeminal tract. Associated findings include a decreased level of consciousness, dysphagia, dysarthria, contralateral limb weakness, and early signs and symptoms of increased intracranial pressure, such as a headache, vomiting, and papilledema.

With massive brain stem infarction or injury, the patient also displays respiratory changes, such as apneustic breathing or periods of apnea, bilateral pupillary dilation or constriction with decreased responsiveness to light, rising systolic blood pressure, a widening pulse pressure, bradycardia, and coma.

Guillain-Barré syndrome. With this polyneuropathic disorder, a diminished or absent corneal reflex accompanies ipsilateral loss of facial muscle control. Muscle weakness, the dominant neurologic sign of this disorder, typically starts in the legs and then extends to the arms and facial nerves within 72 hours. Other findings include dysarthria, dysphagia, paresthesia, respiratory muscle paralysis, respiratory insufficiency, orthostatic hypotension, incontinence, diaphoresis, and tachycardia.

Special Considerations

When the corneal reflex is absent, you’ll need to take measures to protect the patient’s affected eye from injury such as lubricating the eye with artificial tears or ointment to prevent drying. Cover the cornea with a shield and avoid excessive corneal reflex testing. Prepare the patient for cranial X-rays or a computed tomography scan.

Patient Counseling

Teach the patient how to protect his eye from injury. Demonstrate how to apply eye drops correctly.

Pediatric Pointers

Brain stem lesions and injuries are usual causes of absent corneal reflexes in children; Guillain-Barré syndrome and trigeminal neuralgia are less common. Infants, especially those born prematurely, may have an absent corneal reflex due to anoxic damage to the brain stem.

REFERENCES

Gerstenblith, A. T. & Rabinowitz, M. P. (2012). The wills eye manual. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

Holland, E. J., Mannis, M. J., & Lee, W. B. (2013) . Ocular surface disease: Cornea, conjunctiva, and tear film. London, UK: Elsevier Saunders.

Iyer, V. N. , Mandrekar, J. N., Danielson, R. D., Zubkov, A. Y. , Elmer, J. L., & Wijdicks, E. F. (2009) . Validity of the FOUR score coma scale in the medical intensive care unit. Mayo Clinical Procedure, 84(8), 694–701.

Costovertebral Angle Tenderness

Costovertebral angle (CVA) tenderness indicates sudden distention of the renal capsule. It almost always accompanies unelicited, dull, constant flank pain in the CVA just lateral to the sacrospinalis muscle and below the 12th rib. This associated pain typically travels anteriorly in the subcostal region toward the umbilicus.

Percussing the CVA elicits tenderness, if present. (See Eliciting CVA Tenderness.) A patient who doesn’t have this symptom will perceive a thudding, jarring, or pressure-like sensation when tested, but no pain. A patient with a disorder that distends the renal capsule will experience intense pain as the renal capsule stretches and stimulates the afferent nerves, which emanate from the spinal cord at levels T11 through L2 and innervate the kidney.

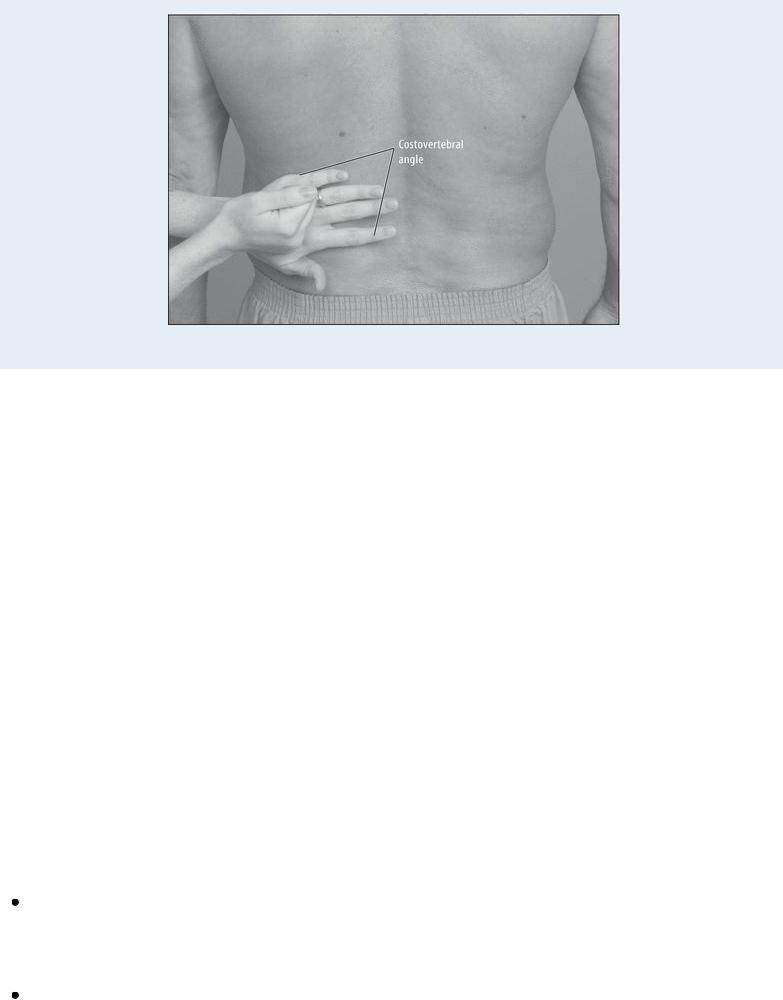

EXAMINATION TIP Eliciting CVA Tenderness

EXAMINATION TIP Eliciting CVA Tenderness

To elicit costovertebral angle (CVA) tenderness, have the patient sit upright facing away from you or have him lie in a prone position. Place the palm of your left hand over the left CVA, then strike the back of your left hand with the ulnar surface of your right fist (as shown). Repeat this percussion technique over the right CVA. A patient with CVA tenderness will experience intense pain.

History and Physical Examination

After detecting CVA tenderness, determine the possible extent of renal damage. First, find out if the patient has other symptoms of renal or urologic dysfunction. Ask about voiding habits: How frequently does he urinate, and in what amounts? Has he noticed any change in intake or output? If so, when did he notice the change? (Ask about fluid intake before judging his output as abnormal.) Does he have nocturia? Ask about pain or burning during urination or difficulty starting a stream. Does the patient strain to urinate without being able to do so (strangury)? Ask about urine color, brown or bright red (urine may contain blood), and cloudiness.

Explore other signs and symptoms. For example, if the patient is experiencing pain in his flank, abdomen, or back, when did he first notice the pain? How severe is it, and where is it located? Find out if the patient or a family member has a history of urinary tract infections, congenital anomalies, calculi, or other obstructive nephropathies or uropathies. Also, ask about a history of renovascular disorders such as occlusion of the renal arteries or veins.

Perform a brief physical examination. Begin by taking the patient’s vital signs. A fever and chills in a patient with CVA tenderness may indicate acute pyelonephritis. If the patient has hypertension and bradycardia, be alert for other autonomic effects of renal pain, such as diaphoresis and pallor. Inspect, auscultate, and gently palpate the abdomen for clues to the underlying cause of CVA tenderness. Be alert for abdominal distention, hypoactive bowel sounds, and palpable masses.

Medical Causes

Calculi. Infundibular and ureteropelvic or ureteral calculi produce CVA tenderness and waves of waxing and waning flank pain that may radiate to the groin, testicles, suprapubic area, or labia. The patient may also develop nausea, vomiting, severe abdominal pain, abdominal distention, and decreased bowel sounds.

Perirenal abscess. Causing exquisite CVA tenderness, perirenal abscess may also produce severe unilateral flank pain, dysuria, a persistent high fever, chills, erythema of the skin and,

sometimes, a palpable abdominal mass.

Pyelonephritis (acute). Perhaps the most common cause of CVA tenderness, acute pyelonephritis is commonly accompanied by a persistent high fever, chills, flank pain, anorexia, nausea and vomiting, weakness, dysuria, hematuria, nocturia, urinary urgency and frequency, and tenesmus.

Renal artery occlusion. With renal artery occlusion, the patient experiences flank pain as well as CVA tenderness. Other findings include severe, continuous upper abdominal pain; nausea; vomiting; decreased bowel sounds; and a high fever.

Renal vein occlusion. The patient with renal vein occlusion has CVA tenderness and flank pain. He may also have sudden, severe back pain; a fever; oliguria; edema; and hematuria.

Special Considerations

Administer pain medication, and continue to monitor the patient’s vital signs and intake and output. Collect blood and urine samples, and then prepare the patient for radiologic studies, such as excretory urography, renal arteriography, and a spiral computed tomography scan.

Patient Counseling

Explain any dietary restrictions the patient needs and tell the patient to drink at least 2 qt (2 L) of fluid daily, unless he has been instructed otherwise. Explain which signs and symptoms of kidney infection he should report. Emphasize the importance of taking the full course of prescribed antibiotics.

Pediatric Pointers

An infant with a disorder that distends the renal capsule won’t exhibit CVA tenderness. Instead, he’ll display nonspecific signs and symptoms, such as vomiting, diarrhea, a fever, irritability, poor skin perfusion, and yellow to gray skin color. In an older child, however, CVA tenderness has the same diagnostic significance as in an adult. Vaginal discharge, vulval soreness, and pruritus may occur in female adolescents.

Geriatric Pointers

Advanced age and cognitive impairment reduce an elderly patient’s ability to perceive pain or to describe its intensity.

REFERENCES

Afhami, M. R., & Salmasi, P. H. (2009) . Studying analgesic effect of preincisional infiltration of lidocaine as a local anesthetic with different concentrations on postoperative pain. Pakistan Journal of Medical Science, 25(5), 821–824.

Soleimanpour, H., Hassanzadeh, K., Aghamohammadi, D., Vaezi, H., & Mehdizadeh, E. M. (2011). Parenteral lidocaine for treatment of intractable renal colic: Case series. Journal of Medical Case Review, 5, 256.

Cough, Barking

(See Also Cough, Nonproductive and Cough, Productive)

Resonant, brassy, and harsh, a barking cough is part of a complex of signs and symptoms that characterize croup syndrome, a group of pediatric disorders marked by varying degrees of respiratory distress. It’s most prevalent in the fall and may recur in the same child.

GENDER CUE

GENDER CUE

Croup syndrome is more common in boys than in girls.

A barking cough indicates edema of the larynx and surrounding tissue. Because children’s airways are smaller in diameter than those of adults, edema can rapidly lead to airway occlusion — a lifethreatening emergency.

EMERGENCY INTERVENTIONS

EMERGENCY INTERVENTIONS

Quickly evaluate the child’s respiratory status, and then take his vital signs. Be particularly alert for tachycardia and signs of hypoxemia. Also, check for a decreased level of consciousness. Try to determine if the child has been playing with any small object that he may have aspirated.

Check for cyanosis in the lips and nail beds. Observe the patient for sternal or intercostal retractions or nasal flaring. Next, note the depth and rate of his respirations; they may become increasingly shallow as respiratory distress increases. Observe the child’s body position. Is he sitting up, leaning forward, and struggling to breathe? Observe his activity level and facial expression. As respiratory distress increases from airway edema, the child will become restless and have a frightened, wide-eyed expression. As air hunger continues, the child will become lethargic and difficult to arouse.

If the child shows signs of severe respiratory distress, try to calm him, maintain airway patency, and provide oxygen. Endotracheal intubation or a tracheotomy may be necessary.

History and Physical Examination

Ask the child’s parents when the barking cough began and what other signs and symptoms accompanied it. When did the child first appear to be ill? Has he had previous episodes of croup syndrome? Did his condition improve upon exposure to cold air?

Spasmodic croup and epiglottitis typically occur in the middle of the night. The child with spasmodic croup has no fever, but the child with epiglottitis has a sudden high fever. An upper respiratory tract infection typically is followed by laryngotracheobronchitis.

Medical Causes

Aspiration of foreign body. Partial obstruction of the upper airway first produces sudden hoarseness and then a barking cough and inspiratory stridor. Other effects of this life-threatening condition include gagging, tachycardia, dyspnea, decreased breath sounds, wheezing, and, possibly, cyanosis.

Epiglottitis. Epiglottitis is a life-threatening disorder that has become less common since the use of influenza vaccines. It occurs nocturnally, heralded by a barking cough and a high fever. The

child is hoarse, dysphagic, dyspneic, and restless and appears extremely ill and panicky. The cough may progress to severe respiratory distress with sternal and intercostal retractions, nasal flaring, cyanosis, and tachycardia. The child will struggle to get sufficient air as epiglottic edema increases. Epiglottitis is a true medical emergency.

Laryngotracheobronchitis (acute). Also known as viral croup, laryngotracheobronchitis is most common in children between ages 9 and 18 months and usually occurs in the fall and early winter. It initially produces a low to moderate fever, a runny nose, a poor appetite, and an infrequent cough. When the infection descends into the laryngotracheal area, a barking cough, hoarseness, and inspiratory stridor occur.

As respiratory distress progresses, substernal and intercostal retractions occur along with tachycardia and shallow, rapid respirations. Sleeping in a dry room worsens these signs. The patient becomes restless, irritable, pale, and cyanotic.

Spasmodic croup. Acute spasmodic croup usually occurs during sleep with the abrupt onset of a barking cough that awakens the child. Typically, he doesn’t have a fever, but may be hoarse, restless, and dyspneic. As his respiratory distress worsens, the child may exhibit sternal and intercostal retractions, nasal flaring, tachycardia, cyanosis, and an anxious, frantic appearance. The signs usually subside within a few hours, but attacks tend to recur.

Special Considerations

Don’t attempt to inspect the throat of a child with a barking cough unless intubation equipment is available. If the child isn’t in severe respiratory distress, a lateral neck X-ray may be done to visualize epiglottal edema; a negative X-ray doesn’t completely rule out epiglottal edema. A chest X- ray may also be done to rule out lower respiratory tract infection. Depending on the child’s age and degree of respiratory distress, oxygen may be administered. Rapid-acting epinephrine and a steroid should be considered.

Make sure to observe the child frequently, and monitor the oxygen level. Provide the child with periods of rest with minimal interruptions. Maintain a calm, quiet environment and offer reassurance. Encourage the parents to stay with the child to help alleviate stress.

For recurrent episodes of croup syndrome at home, instruct the parents to create steam by running hot water in a sink or shower and sit with the child in the closed bathroom; this may help relieve subsequent attacks. The child may also benefit from being brought outside (properly dressed) to breathe cold night air.

Patient Counseling

Teach the parents or caregiver how to evaluate and treat recurrent episodes of croup syndrome, and how to administer prescribed medications.

REFERENCES

Hall, C. B., & McBride, J. T. (2010). Acute laryngotracheobronchitis (croup). In: Mandell, G. L., Bennett, J. E., Dolin, R., eds. Mandell, Douglas, and Bennett’s principles and practice of infectious diseases (7th ed., pp. 825–829). Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier.

Zoorob, R., Sidani, M., & Murray, J. (2011). Croup: An overview. American Family Physician, 83, 1067–1073.

Cough, Nonproductive