Граматика / English Syntax

.pdf

136 |

More on Clauses |

|

|

while the subordinate clause in (15) is nonfinite and not introduced by a subordinating conjunction.

We haven’t so far discussed sentences that contain subordinate clauses that have a function other than DO, e.g. Subject or Adjunct (cf. Chapter 5), as in (16) and (17):

(16)[That Ken adores Nadia] annoys Jenny.

(17)I will repair it [when I return].

(18)

|

|

|

S/MC |

|

|

||

|

|

SubC |

|

I |

|

|

VP |

|

|

|

þ |

þ |

present] |

Spec |

V0 |

|

|

|

[ Tns, |

|

|||

|

|

|

[þAgr] |

|

|

|

|

Comp |

NP |

I |

VP |

|

|

|

|

Spec |

N0 |

|

Spec V0 |

|

|

V |

NP |

VNP

|

|

Spec |

N0 |

Spec |

N0 |

|

[þTns, þpresent] |

|

|

|

|

|

[þAgr] |

|

|

|

|

|

N |

|

N |

|

N |

That |

Ken |

adores |

Nadia |

annoys |

Jenny |

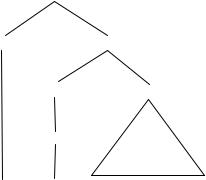

(16) can be represented as follows in a tree diagram:

As for (17), notice that the subordinate clause is positioned after the Direct Object, and that its function is Adjunct (cf. Section 5.6). Because the whenclause is not a Complement of the verb repair, it cannot be analysed as its sister in a tree diagram. Instead, it must be adjoined as a sister to the V0 repair it:

|

|

|

|

|

The I-Node |

|

|

|

137 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

(19) |

S/MC |

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||

|

NP |

I |

|

VP |

|

|

|

|

|

Spec |

N0 |

|

|

Spec |

V0 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

V0 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

V |

NP |

|

SubC |

|

|

|

þ |

Tns, |

þ |

present] Spec |

N0 |

NP |

I |

|

VP |

|

N [ |

|

|

||||||

|

[þAgr] |

|

|

Conj |

|

þ |

þ |

present] Spec V0 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

[ Tns, |

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

N |

|

[þAgr] |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Spec |

N0 |

|

|

V |

|

|

|

|

|

|

N |

|

|

|

|

I |

will |

repair |

it when |

I |

|

|

return |

|

8.2.2Clauses functioning as Complements within Phrases

In Chapter 7 we saw that not only verbs can take clausal complements, other lexical Heads can too. Consider the bracketed phrases in the examples below, taken from Table 7.2:

(20)The article was about [NP their realisation that all is lost]

(21)I am [AP so eager to work with you]

(22)He is uncertain [PP about what you said to me]

The Heads in each case are in bold, the Complements are in italics. The clausal Complements in each case are subordinate clauses. In the NP and AP they give more information about the content of their associated Head. In the PP the clause identifies the nature of the uncertainty mentioned in the sentence.

Exercise

Draw the trees for these phrases. Use triangles for the clausal Complements.

138 |

More on Clauses |

|

|

Your answers should look like this:

(23)

NP

Spec N0

NClause

their realisation |

that all is lost |

(24)

AP

Spec A0

AClause

so |

eager |

to work with you |

(25)

PP

Spec P0

PClause

about what you said to me

Because the clauses in each case are Complements, they are represented as sisters of their Heads.

8.2.3Clauses functioning as Adjuncts within Phrases

Apart from inside VPs (see Section 7.2 above), clausal Adjuncts are also found in NPs. Here they have a special name: they are called relative clauses,

The I-Node |

139 |

|

|

and can be introduced by a Wh-word or by that. There are two examples in Table 7.3 of the previous chapter. Here are some further examples:

(26)Do you remember [NP that summer, which was so sunny]?

(27)Do you remember [NP that summer which was so sunny]?

(28)I’m worried about [NP the watch that was stolen], not the one on the table.

Imagine (26) being uttered in a situation where the interlocutors know which particular summer is being referred to, say last year’s summer. In this case the relative clause does not add further information that contributes to identifying the summer in question. We call it a nonrestrictive relative clause. Note the comma, which marks the relative clause o intonationally, i.e. there is a pause after the word summer. (Read the sentence out aloud to see what I mean.) Consider now (27). It looks exactly the same as (26), except that this time there is no comma, which means that there is no pause after summer. When uttered in this way the relative clause does single out a particular summer for the interlocutors, for example a hot summer in a series of wet ones. (Again, read the sentence out aloud.) We call such a clause a restrictive relative clause. In (28) the clause that was stolen is a further example of a restrictive relative clause, because it uniquely identifies a particular watch. Should we distinguish structurally between restrictive and nonrestrictive relative clauses? Because the distinction between them is arguably a semantic one, and because they often depend for their interpretation on a particular context of utterance, we will not structurally distinguish the way they are positioned relative to their associated Heads: we will treat both restrictive and nonrestrictive relative clauses functionally as Adjuncts (i.e. they are adjoined to N0). Thus, (29) represents the NP in both (26) and (27), while (30) represents the NP in (28):

(29)

NP

Spec N0

N0 Clause

N

that summer which was so sunny

140 |

More on Clauses |

|

|

(30)

NP

Spec N0

N0 Clause

N

the |

watch |

that was stolen |

Key Concepts in this Chapter

The I-node

subordinate clauses functioning as DO, Subject and Adjunct relative clauses (restrictive, nonrestrictive)

Exercises

1.True or false? In the sentence Linda can arrange the event:

(i)can takes the VP arrange the event as its Complement

(ii)can has moved from inside the VP to the I-node

(iii)can is positioned in the I-node, and has not moved

(iv)can is a present tense aspectual auxiliary verb

2.In accordance with X-bar theory, draw complete trees (i.e. include all the Specifiers and all the I-nodes with the relevant features) of the following phrases/sentences. Treat be as a main verb.

(i)I will go.

(ii)She rode her bicycle slowly.

(iii)Seamus can speak Chinese.

(iv)Elaine should not enrol.

(v)[That we will succeed] will surprise nobody.

(vi)I prefer you to stay in London.

(vii)She phoned because she likes you.

(viii)I thought that she was a student of law.

Further Reading |

141 |

|

|

(ix)We will have a picnic, when Frank arrives.

(x)He is grumpy, but he is kind.

(xi)We will not budge.

(xii)Although she wrote the story, she disowns it.

3.How can the following utterance be taken as evidence to support our claim that modal auxiliary verbs are positioned in ‘I’?

(i)He might, and I stress might, pass his exams.

*4. Draw trees for the italicised phrases below. Use triangles for the subordinate clauses.

(i)Her father, who was arrested, protested his innocence.

(ii)I am so happy to leave England.

*5. Distinguish structurally between the italicised phrases (i) and (ii) in full tree diagrams (so no triangles!).

(i)He denied the fact that she is clever.

(ii)The fact that she is clever is important.

Further Reading

The I-node is a di erent sort of Head than we have come across so far. It is a functional category, as opposed to a lexical category (such as N, V, A and P). Chomsky (1986) proposed that the I-node be given its own maximal projection, namely Inflection Phrase (IP). In the same way complementisers head Complementiser Phrases (CP). See Radford (1988), Haegeman (1994) and Ouhalla (1999) for more details. It has furthermore been proposed that a number of additional functional categories, e.g. tense, agreement and aspect, also head their own maximal projections, so that we can speak of

Tense Phrases (TP), Agreement Phrases (AgrP) and Aspect Phrases (AspP), among others. See Webelhuth (1995) for an historical overview of developments in X0-theory.

On relative clauses, see Quirk et al. (1985, pp. 1244–60). On nonrestrictive relative clauses, see Fabb (1990) and Burton-Roberts (1999).

9 Movement

This chapter will look at four di erent ways in which elements, or strings of elements, can be moved in a sentence. I will first discuss verb movement and NP-movement, then movement in interrogative sentences and finally Wh-movement. I will finish the chapter with a section on the structure of sentences containing sequences of auxiliaries.

9.1Verb Movement: Aspectual Auxiliaries

In the previous chapter we argued that modal auxiliaries are not positioned in VP, but in ‘I’, and we used the sentences in (1) and (2) to demonstrate this.

(1)My brother will not bake a cake.

(2)My brother will perhaps not bake a cake.

In (1) the modal auxiliary will is positioned before the negative element not, which we argued to be in the Specifier position of VP. As there are no further slots to the left of the Specifier in VP, we concluded that the modal must be outside VP. In (2) the sentence adverb perhaps is positioned between the modal will and not. On the assumption that sentence adverbs are directly dominated by S, the conclusion must again be that the modal cannot be inside VP. Furthermore, we observed that modals are always finite, and that the ‘I’-node is therefore a natural location for them, given the fact that it contains the tense feature (see Section 8.1).

But what about the aspectual auxiliaries have and be in sentences like (3) and (4)? Where are these positioned?

(3)He has broken the mirror.

(4)I am dreaming.

Let’s look at these sentences more closely. In (3) the last two constituents are the verb broken (the nonfinite past participle form of the main verb break) and the Noun Phrase the mirror, which functions as a Direct Object. Now, we know that a main verb þ DO form a V-bar (V0), and that this V0 is

142

Verb Movement: Aspectual Auxiliaries |

143 |

|

|

a sister of a Specifier. We also know that the Specifier node and V0 are dominated by VP, so we assign the structure in (5) to the sequence broken the mirror:

(5) |

VP |

|

|

Spec |

V0 |

|

V |

NP |

|

broken |

the mirror |

We still need to account for the finite aspectual auxiliary has. We will assume that this verb takes the VP broken the mirror as its Complement. In a tree diagram this VP should therefore be represented as the sister of have, as in (6), the full representation of (3) (the Specifier position of the lower VP has been left out to make the tree visually easier to interpret):

(6) |

S |

|

|

NP |

I |

VP |

|

|

[þTense, þpresent] Spec |

V0 |

|

|

[þAgr] |

V |

VP |

|

|

||

|

|

|

V0 |

|

|

V |

NP |

He |

|

have broken |

the mirror |

Notice that in this tree the aspectual auxiliary have is inserted in its base form, which raises the question how it ends up in its finite form has. The answer is that the aspectual auxiliary acquires its inflectional present tense ending by moving from the VP that immediately dominates it into the I-node, as indicated below:

144 |

|

|

Movement |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

(7) |

|

S |

|

|

|

NP |

|

I |

VP |

|

|

þ |

þ |

present] |

Spec |

V0 |

|

[ Tense, |

|

|

|||

[þAgr] |

|

|

V |

|

VP |

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

V0 |

|

|

|

|

V |

NP |

He |

|

has |

– |

broken |

the mirror |

This process we refer to as verb movement.

Exercise

What would be the structure of sentence (4)? Assuming that the aspectual auxiliary moves from VP into ‘I’, draw the tree diagram for (4). Indicate the movement with an arrow, as above. You may omit irrelevant nodes, such as the Specifier position of the lowest VP.

The tree diagram for (4) is as in (8):

(8) |

|

S |

|

|

NP |

|

I |

VP |

|

þ |

þ |

present] |

Spec |

V0 |

[ Tense, |

|

|||

[þAgr] |

|

|

V |

VP |

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

V0 |

|

|

|

|

V |

I |

|

am |

– |

dreaming |

Here, too, the aspectual moves from the position in VP marked ‘–’ to ‘I’ in order for the verb to acquire its present tense form. Notice that as the verb dream is an intransitive verb, there are no further Complements present in the lowest VP.

Verb Movement: Aspectual Auxiliaries |

145 |

|

|

You may well be wondering why we are positing movement of aspectual auxiliaries into ‘I’. Why don’t we simply assume that the inflectional features are lowered from ‘I’ into the VP, exactly in the same way as was suggested in Chapter 8 for main verbs in simple sentences like (9)?

(9)Ted opened the window.

Well, there is evidence that we need to posit movement for the aspectuals, and this evidence concerns sentences involving negative elements, sentence adverbs or modals, or a combination of these. Consider the following examples:

(10)He has not broken the mirror.

(11)I am not dreaming.

Notice that both sentences contain not. As we have seen, this element is positioned in the Specifier of VP. This being so, and there being no further slots inside VP to the left of the Specifier, the most obvious position for the aspectuals is inside ‘I’. But if have and be are inside VP in trees like (6), but in ‘I’ in (10) and (11), then we need to account for this di erence in position. One way of doing so is by positing movement of the aspectuals from VP to ‘I’. This would then also explain how they end up in their finite forms (cf.

*He have not broken the mirror/*I be not dreaming). Here is the tree for (10):

(12) |

S |

|

|

|

|

|

NP |

I |

|

|

VP |

|

|

|

[þTense, þpresent] |

Spec |

|

V0 |

|

|

|

[þAgr] |

|

|

V |

|

VP |

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

V0 |

|

|

|

|

|

V |

NP |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

He |

has |

not |

– |

broken |

the mirror |

|

Exercise

Now draw the tree for (11). Use an arrow to show the movement of the aspectual auxiliary. As before, you may leave out irrelevant nodes such as the Specifier position of the lowest VP.