Lesson 4

.docxLesson 4: Metaphysics

Introduction Metaphysics is one of the oldest areas of philosophical thought. From a purely linguistic standpoint, metaphysics is a combination of two root words: meta(meaning "more than") and physics (which refers to the physical world that surrounds us). Thus, it could be said that metaphysics is a study of things beyond our physical world or "beyond physics".

Therefore, in the context of this lesson, metaphysics will be defined as "…A sustained and rational study of what there is and the ultimate nature of what there is" (Geirsson and Losonsky 1998). That is, it is a methodical, conscious effort to think about the universe, what it is, and what it is made of.

The sections that follow will detail some of the most prevalent metaphysical positions, along with a brief explanation of each. A more historical overview will be presented in a later lesson.

Monism

One of the oldest of the metaphysical position is monism, dating back to the thought of many pre-Socratic philosophers. This theory holds that all of reality is made of one and only one fundamental substance. There are two major sub-categories of monism: material monism, which believes the world (kosmos) or the universe is comprised of a single, physical substance or material; and idealism, which is the belief that reality is "…Spiritual or made up of ideas" (Pojman, 2000). Monism of both types are still practiced today, such as in the thought of Bertrand Russell and John Bickle (material); and in the Hindu religion and Christian Science (idealism), among others (Pojman, 2000).

Dualism

Traditionally, dualism is a metaphysical system that acknowledges both a physical (matter) and a spiritual or mental (mind) component to the universe. The extent to which these two distinct essences interact has been a subject of heated metaphysical debate for centuries. Can matter affect the mind? Can mind affect matter (hence, the old "mind over matter" saying)? Generally, it is a theory that holds "…Mind and matter are two distinct things" (Honderich 1995).

The first major proponent of dualist philosophy was Plato, who espoused what has become known as "classical dualism". In his work, Phaedo, Plato stated that "…the true substances are not physical bodies, which are ephemeral, but the eternal Forms of which bodies are imperfect copies. These Forms not only make the world possible, they also make it intelligible, because they perform the role of universals, or what Frege called ‘concepts'" (Robinson 2008). Thus, a person's mind, existing outside the physical world, would have an actual affinity for these Forms, which are themselves ideal representations of everything in the physical universe. Simply put, Plato believed that if one saw a chair for the first time, there is a form in the person's brain that would tell them that it is a chair, and it is meant to be sat upon.

Aristotle, Plato's most famous student, rejected the notion of abstract Forms in the universe and instead claimed that the matter and form of objects were fused together to form substance. That is, mind and body combined to form what we observe in the physical universe. Aristotle, unlike Plato, believed that mind (the Forms) could not cause movement nor change (both of which could be observed in the real world), nor did they help a person "…To understand what is real and what is knowable" (Osborne 1992). In this way, the very influential Aristotle brought dualism down to Earth and made it accessible to physical beings.

Dualistic metaphysics dominated much of philosophy throughout the intervening centuries, making some progress here and there and leaving its mark on medieval thought, as well as the doctrines of the Abrahamic religions (Judaism, Christianity, and Islam). During this period debates raged on the nature of mind and matter and how they were able to interact in a meaningful way in the universe. Then, in the mid-1600s, a new thinker arose in France who would change the traditional formulations of dualism forever.

The beginning of modern dualism is typically credited to the French philosopher René Descartes, also called the "Father of Modern Philosophy". In his work, Meditations, Descartes lays the groundwork for a new kind of dualism in which there are two separate and distinct substances in the universe (Robinson 2008). He claimed that knowledge of God, self, and all external things was only possible through the mind. His famous declaration "I think, therefore I am" was the beginning of this metaphysical worldview, sometimes called Cartesian dualism.

Pluralism

Unlike material monists, pluralists believe that the physical universe is comprised of a number of different first principles or elements. Ancient Greek philosophers such as Anaxagoras and Empedocles are considered to be founding fathers of pluralism. They believed all things that currently exist have existed since the beginning of time. Anaxagoras, in particular, introduced the concept of nous as an ordering force of the universe. Also considered to be the mind, nous causes motion, which separated the tangled mass of all things into the ordered universe we now observe.

Emanationism

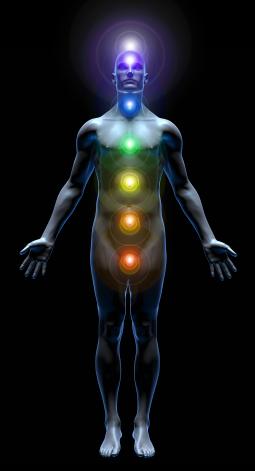

Credited to the Greek philosopher Plotinus (AD 204-270), emanationism contends that all of reality emanates or "flows forth" from a central source, called "The One." The belief in emanation forms the basis of many mystic and metaphysical traditions around the world, including the Gnostics, Kabbalah, Sufism, Rosicrucianism, Neoplatonism, Buddhism, Hinduism, and more.

This metaphysical approach, especially the writings of Plotinus and the other Neo-Platonists, has had significant influence on pagan, Christian, Jewish, Islamic, and Gnostic metaphysicians, as well. The mystical components of this worldview put it at direct opposition to both creationism (because the creator and the creation are separate and distinct) and to strict materialism (which claims there is no subjective underlying nature to what exists in the universe).

Atomism

Building on the thoughts of the pluralist school, the atomists created a theory that stated all matter in the universe is comprised of atoms--very small, indestructible units of matter. These indivisible units, along with the spaces between them (called "void") are capable of being shaped into innumerable forms and objects, which comprise the universe. Democritus and his teacher, Leucippus, believed these atoms to be eternal and always moving in predetermined ways. As such, the metaphysics of the atomists tended to be very mechanistic and deterministic in nature. To this day, Democritus is credited with laying the foundations for modern atomic science, which would not develop for many more centuries.

Materialism

Simply put, materialists believe that there is nothing besides matter and its associated properties in all of reality. The universe is comprised of physical substance and nothing more. Therefore, there is no reference to dualistic notions of "mind" or any credence given to the concept of deity or any other thing that would exist beyond what can be perceived by the senses (empirically verified). It varies from naturalism, with which it is closely compatible, in that strict materialism only concerns itself with the composition of things (i.e., "what are things made of?").