- •The last third of the 18th century

- •Philosophical schools and tendencies of XIX century

- •German idealism

- •Utilitarianism

- •The Marxist Philosophy

- •Karl Heinrich Marx

- •Friedrich Engels

- •Dialectical materialism

- •Materialism

- •Dialectics

- •The three laws of dialectics:

- •Existentialism

- •Positivism

- •Pragmatism (Pragmaticism)

- •British idealism

- •Transcendentalism

- •Thank you for attention!

- •Made by the student of the

XIX

CENTURY PHILOSOPH Y

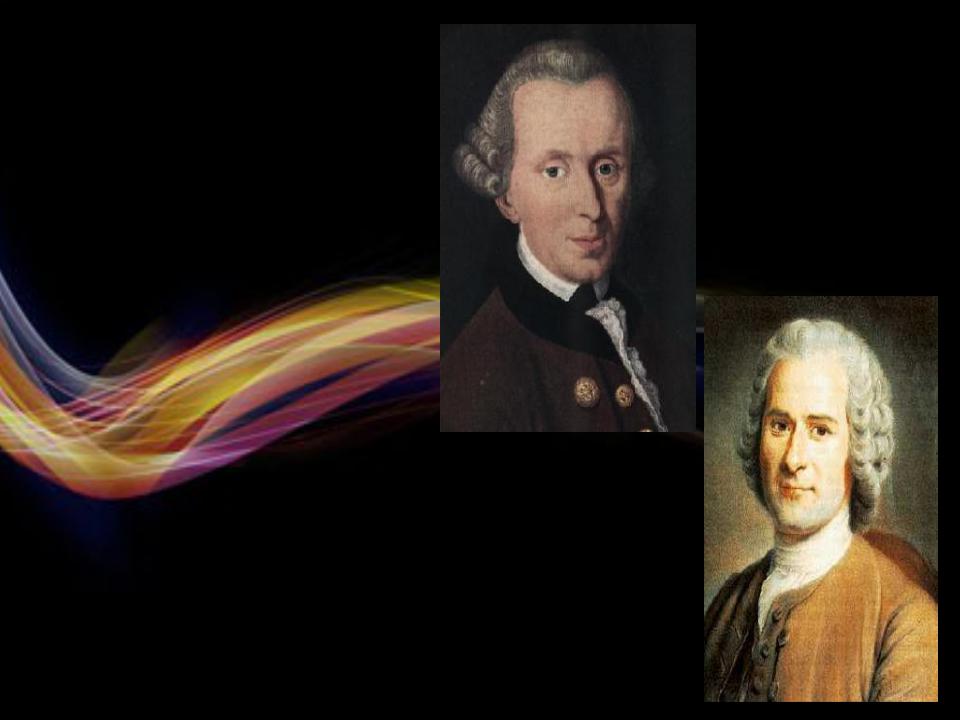

The last third of the 18th century |

Immanuel Kant |

|

|

produced a host of ideas and works |

|

which would both systematize |

|

previous philosophy, and present a |

|

deep challenge to the basis of how |

|

philosophy had been systematized. |

|

Immanuel Kant is a name that most |

|

would mention as being among the |

|

most important of influences, as is |

|

Jean-Jacques Rousseau. While both |

|

of these philosophers were products |

|

of the 18th century and its |

|

assumptions, they pressed at the |

|

boundaries. In trying to explain the |

|

nature of the state and government, |

|

Rousseau would challenge the basis |

|

of government with his declaration |

|

that "Man is born free, but is |

|

everywhere in chains". Kant, while |

|

attempting to preserve axiomic |

|

skepticism, was forced to argue that |

|

we do not see true reality, nor do we |

|

speak of it. |

Jean-Jacques Rousseau |

|

Philosophical schools and tendencies of XIX century

German idealism

One of the first philosophers to attempt to grapple with Kant's philosophy was Johann Gottlieb Fichte, whose development of Kantian metaphysics became a source of inspiration for the Romantics. In Wissenschaftslehre, Fichte argues that the self posits itself and is a self-producing and changing process. Friedrich Wilhelm Joseph Schelling, a student of Fichte, continued to develop many of the same ideas and was also assimilated by the Romantics as something of an official philosopher for their movement. But it was another of Fichte's students, and former roommate of Schelling, who would rise to become the most prominent of the post-Kantian idealists: Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel. Arthur Schopenhauer, rejecting Hegel, called for a return to Kantian idealism.

Friedrich Wilhelm Josep

h Schelling

Georg Wilhelm Fried |

Arthur Schopenhauer |

|

rich Hegel |

||

|

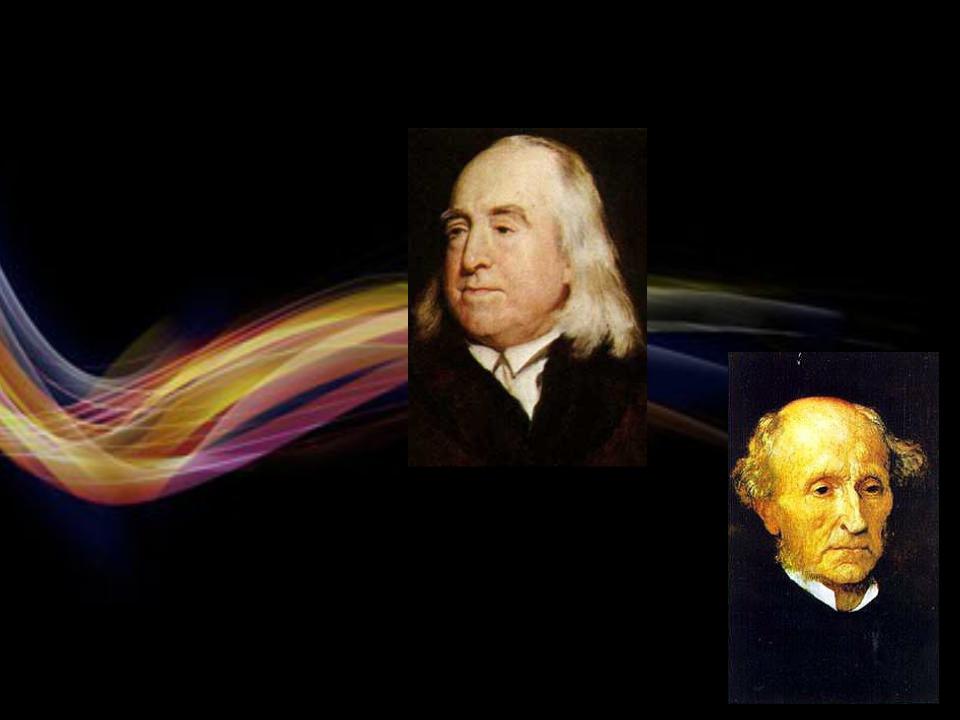

Utilitarianism

Jeremy Bentham

In early 19th century Britain, Jeremy Bentham and

John Stuart Mill promoted the idea that actions are right as they maximize happiness, and happiness alone.

John Stuart Mill

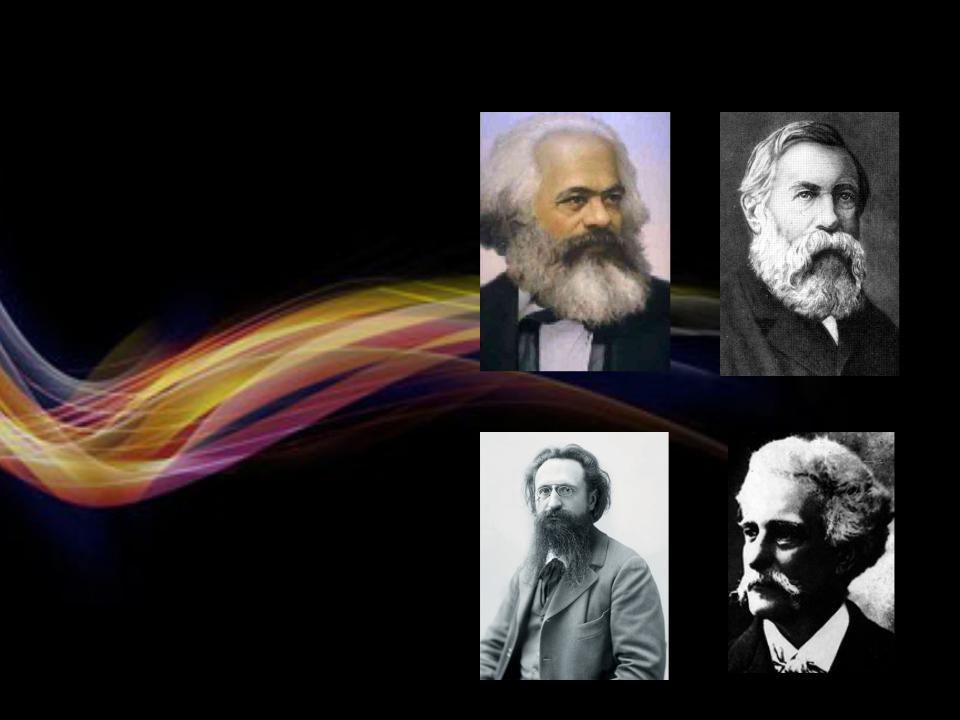

The Marxist Philosophy

The term Classical Marxism denotes the theory propounded by Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels Friedrich Engels. As such, Classical Marxism distinguishes between “Marxism” as broadly perceived, and “what Marx believed”; thus, in 1883, Marx wrote to the French labour leader Jules Guesde and to Paul Lafargue (Marx’s son-in-law) — both of whom claimed to represent Marxist principles

— accusing them of “revolutionary phrase-mongering” and of denying the value of reformist struggle; from which derives the paraphrase: “If that is Marxism, then I am not a Marxist”. To which, the US Marx scholar Hal Draper remarked, “there are few thinkers in modern history whose thought has been so badly misrepresented, by Marxists and anti-Marxists alike”.

Karl Marx |

Friedrich Engels |

Jules Guesde |

Paul Lafargue |

Karl Heinrich Marx

Karl Heinrich Marx (5 May 1818—14 March 1883) was a German philosopher, political economist, and socialist revolutionary, who addressed the matters of alienation and exploitation of the working class, the capitalist mode of production, and historical materialism. He is famous for analysing history in terms of class struggle, summarised in the initial line introducing the

Communist Manifesto (1848): “The history of all hitherto existing society is the history of class struggles”. His ideas were influential in his time, and it was greatly expanded by the successful Bolshevik October Revolution of 1917 in Imperial Russia.

Friedrich Engels

Friedrich Engels (28 November 1820–5 August 1895) was a nineteenth century German political philosopher and Karl Marx’s co-developer of communist theory. Marx and Engels met in September 1844; discovering that they shared like views of philosophy and socialism, they

collaborated and wrote works such as Die heilige Familie (The Holy Family). After Karl Marx’s death in

1883, Friedrich Engels became the editor and translator of Marx’s writings.

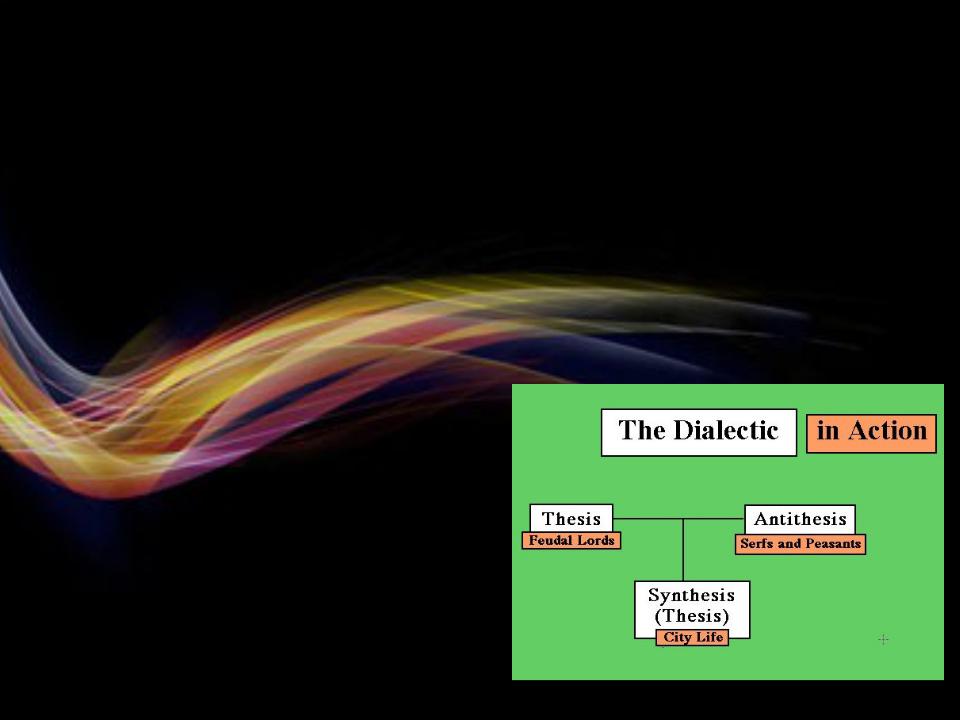

Dialectical materialism

Dialectical materialism is a strand of Marxist theorizing, composed of a synthesis of Hegel's dialectics and Ludwig Andreas Feuerbach's materialism, based upon an interpretation of Karl Marx's work. According to certain followers of Karl Marx's thinking, it is the philosophical basis of Marxism, although this remains a controversial assertion due to the disputed status of science and naturalism in Marx's thought.

The basic idea of dialectical materialism is that every economic order grows to a state of maximum efficiency, while at the same time developing internal contradictions or weaknesses that contribute to its decay. D.M. uses the concepts of thesis, antithesis and synthesis to explain the growth and development of human history.

Materialism

In essence, materialism answers the fundamental question of philosophy by asserting the primacy of the material world: in short, matter precedes thought. Materialism holds that the world is material, that all phenomena in the universe consist of matter in motion, wherein all things are interdependent and interconnected and develop in accordance with natural law, that the world exists outside us and independently of our perception of it, that thought is a reflection of the material world in the brain, and that the world is in principle knowable. “The ideal is nothing else than the material world reflected by the human mind, and translated into forms of thought.” – Karl Marx.

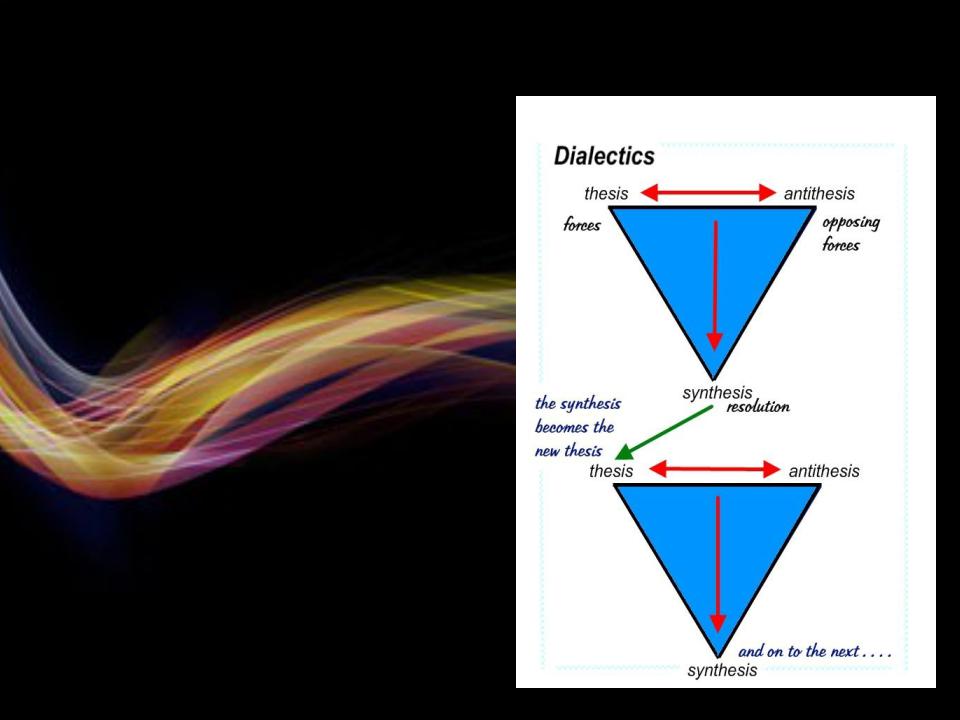

Dialectics

Dialectics is the science of the general and abstract laws of the development of nature, society, and thought. Its principal features are the next. The universe is not a disconnected mix of things isolated from each other, but an integral whole, with the result that things are interdependent. Nature – the natural world or cosmos – is in a state of constant motion: “All nature, from the smallest thing to the biggest, from a grain of sand to the sun, from the protista to man, is in a constant state of coming into being and going out of being, in a constant flux, in a ceaseless state of movement and change.” – Friedrich Engels, Dialectics of Nature.