- •Preface

- •Contents

- •Contributors

- •1 The Nature of Culture: Research Goals and New Directions

- •References

- •Abstract

- •The Primitive Tasmanian Image

- •Assessment of a Minimum of Cultural Capacities from a Set of Cultural Performances

- •Conclusions: Lessons from Tasmania

- •References

- •3 Culture as a Form of Nature

- •Abstract

- •The Status Quo of Nature

- •Culture as a Variation of Nature

- •The Dense Context of Nature

- •The Problem of Conscious Inner Space

- •Consciousness as a Social Organ

- •The Meaning of Signs

- •The Role of Written Language

- •References

- •Abstract

- •Introduction

- •Evidence for Animal Social Learning, Traditions and Culture

- •Social Information Transfer

- •Traditions

- •Multiple-Tradition Cultures

- •Cumulative Culture

- •Multiple-Tradition Cultures

- •Cultural Content: Percussive Technology

- •Social Learning Processes

- •Concluding Remarks

- •References

- •Abstract

- •Introduction

- •Typology of Limestone Artifacts

- •Cores and Core-Tools

- •Flakes and Flake-Tools

- •Technology of Limestone Artifacts

- •Cores and Core-Tools

- •Flakes and Flake-Tools

- •Cognitive Abilities

- •Acknowledgements

- •References

- •Abstract

- •Introduction

- •Technological Transformations

- •Cultural Transformations

- •Closing Remarks on the Nature of Homo sapiens Culture

- •Acknowledgements

- •References

- •7 Neanderthal Utilitarian Equipment and Group Identity: The Social Context of Bifacial Tool Manufacture and Use

- •Abstract

- •Introduction

- •Conclusions

- •Acknowledgements

- •References

- •Abstract

- •Introduction

- •Style in the Archaeological Discourse

- •The Archaeological Evidence

- •Discussion and Conclusions

- •Acknowledgements

- •References

- •Abstract

- •Introduction

- •Human Life History

- •Cognitive Development in Childhood

- •The Evolutionary Importance of Play

- •What Is Play?

- •Costs and Benefits of Play

- •Why Stop Playing?

- •Fantasy Play

- •Acknowledgements

- •References

- •Abstract

- •Introduction

- •What Is Culture?

- •Original Definitions

- •Learned Behavior

- •Culture and Material Culture

- •Models of Culture in Hominin Evolution

- •Conclusion

- •Acknowledgments

- •References

- •11 The Island Test for Cumulative Culture in the Paleolithic

- •Abstract

- •Introduction

- •The Island Test for Cumulative Culture

- •Geographic Variation

- •Temporal Variation

- •The Reappearance of Old Forms

- •Conclusions

- •Acknowledgements

- •References

- •12 Mountaineering or Ratcheting? Stone Age Hunting Weapons as Proxy for the Evolution of Human Technological, Behavioral and Cognitive Flexibility

- •Abstract

- •Introduction

- •Single-Component Spears

- •Stone-Tipped Spears

- •Bow-and-Arrow Technology

- •But, Is It Ratcheting?

- •Or Is It Mountaineering?

- •Acknowledgments

- •Index

12 Stone Age Hunting Weapons |

141 |

use of a spearthrower and dart, a hammer and chisel, or a fishing rod with line and hook. Key is therefore not the artifacts themselves or their apparent complexity, but the behavioral and/or cognitive components or concepts they represent (Lombard and Haidle 2012; Williams et al. 2014). Once the concept of symbiotic technologies is understood, different elements and series of elements can be adapted and grouped in multiple ways, and in sequences of various length and complexity, to achieve diverse results. For example bows can be:

•grouped with drill bits, weights and handling pieces to use as bow drills;

•used with palm protectors, base-wood and tinder as fire drills;

•used as simple, violin-like instruments, stroked with a stick and applying the mouth cavity or a gourd as sound box, as is done by the Kalahari San in Southern Africa;

•or plucked (non-symbiotically) with the fingers like a one-string guitar, also demonstrated by the Kalahari San.

The main evolutionary advantage of symbiotic technologies, such as a bow-and-arrow set, is considered the amplification of conceptual, technological and behavioral modularization and flexibility where almost endless combinations of single elements or chains of operations can be linked in a variety of ways to reach single or multiple goals (Lombard and Haidle 2012). Amplified conceptual, technological and behavioral modularization allows for a range of cognitive and cultural complexity and flexibility, basic to human behavior today. It facilitates communication, and the manipulation and/or exploration of our surroundings with the most complex of technologies, or allows us to choose the simplest of solutions for any given circumstance, all within seconds of each other or even simultaneously. Thus, we are able to speak on a mobile phone, invisibly linked to a satellite, with someone on the other side of the globe, while eating sushi with a pair of chopsticks.

But, Is It Ratcheting?

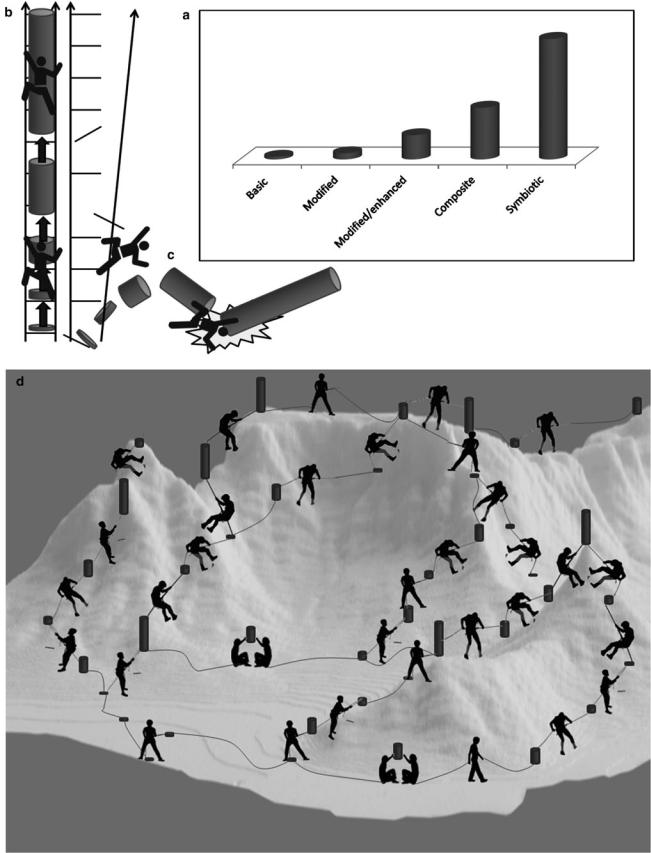

The above summary seems to indicate five major evolutionary steps relating to tool behavior and material culture (Fig. 12.3a):

(a)using objects (basic culture, e.g., chimpanzees using sticks to hunt or Australopithecines using unmodified bone tools);

(b)modifying objects with other objects before using them (limited modularization, represented in archaeological assemblages associated with the Homo lineage and possibly even present in some Australopithecine assemblages, e.g., Oldowan stone tools);

(c)modifying objects with other objects and enhancing them with the aid of external agents (e.g., fire) before using them (modularization, represented in archaeo-

logical assemblages associated with the Homo lineage, e.g., the wooden spears from Schöningen);

(d)combining modified/enhanced objects to make composite tools with new properties (composition or advanced modularization, shared by Homo sapiens, H. neanderthalensis, H. heidelbergensis, and archaic modern humans, e.g., stone-tipped spears or other composite tools);

(e)simultaneously, and actively manipulating different modified and/or composite artifacts in a mechanical configuration to achieve new results that cannot be attained when tools are used on their own or successively (technological symbiosis or amplified modularization, possibly exclusive to Homo sapiens, e.g., or spearthrower-and-dart technology (but, more in-depth work is needed on other technological configurations).

At first glance, the above sequence may seem to support the notion of cumulative culture in the sense that changes are built upon one another and accumulated over time so that problems need not be solved from scratch (Tennie et al. 2009). Cumulative culture has, however, been compared to a ratchet or the ratchet effect, “where modifications and improvements stay in a population fairly readily (with relatively little loss or backward slippage) until further changes ratchet things up [my emphasis] again” (Tennie et al. 2009:2405). In another description of the ratchet effect, thinking is seen as a “canalized process” that builds upon previous knowledge structures, speeding up developmental processes at the cost of constructing a “rigid system” (Riegler 2001). Here a concept (idea, technology, cultural expression, etc.) is seen as the hierarchical scaffolding of rules and concepts channeled into a single direction or upwards (Fig. 12.3b). According to this view, however, the entire system will collapse when old components are removed (Fig. 12.3c) (Riegler 2001). These unidirectional and rigid definitions of ratcheting probably apply to some biological systems, or the life history of a particular technological or cultural system within a specific spatio-temporal context. But, it is not a truism regarding all change and variability in human behavioral, cognitive or cultural evolution.

When it comes to the evolution of human behavior, culture and the way we think, things are never simple. A closer look at the archaeological and historical records – the only ones that attest to past human behavioral, cognitive and cultural or technological aptitude – does not show uninterrupted accretion of innovations or exponential growth in complexity under all circumstances. Transitions between cultural concepts, ideologies and/or technologies are not

142 |

M. Lombard |

12 Stone Age Hunting Weapons |

143 |

b Fig. 12.3 a Simplified, hypothetical graphic expression of the thought-and-action volumes of the different effective chains of production and use of basic, modified, modified and enhanced, composite and symbiotic technologies. b Cumulative culture ‘ratcheting up’ (e.g., Tennie et al. 2009). c The prediction is that the entire system will collapse when old components are removed (e.g., Riegler

2001). d Hypothetical illustration of how the rugged fitness landscape and mountaineering analogy helps to explain human cultural, behavioral and technological evolution and flexibility. Here groups can move in any direction, yet remain anchored without necessarily being rigid or prone to total collapse when a previous concept fails them or their current situation

always ratchet-like (moving upwards or channeled in a single direction) through time and space (Fig. 12.3b), and removing some components (old or new) does not always result in collapse (Fig. 12.3c). Throughout human history, there are episodes of technological, organizational or ideological change in multiple directions, and of simplification. There is also evidence of the loss and re-invention of concepts, ideologies and technologies (e.g., Diamond 2005; d’Errico and Stringer 2011; Lombard and Parsons 2011). Using hunting technologies as proxy for some aspects of human evolution, it appears for example, that people were hunting with bows and arrows (as well as other weapon systems) as early as 64 ka in southern Africa (Backwell et al. 2008; Wadley and Mohapi 2008; Lombard and Phillipson 2010; Lombard 2011). However, after *59 ka they seem to have stopped using this complex system in favor of hand-delivered spear hunting (Lombard 2005; Lombard and Parsons 2011), only to start hunting with bows and arrows again after *35 ka (Mohapi 2007; Villa et al. 2010).

The South African example does not represent the first or only time this happened. Even though mechanically-projected weaponry is a crucial component of all recent human subsistence strategies (Shea 2009), its use was by no means continuous in all societies. Throughout human history, it has been adopted, discarded and adopted again. Relatively recent (Holocene) examples would include Polynesians and Melanesians who abandoned the use of bows and arrows in war, Polar and Dorset Eskimos who ‘lost’ the bow and arrow, and Aboriginal Australians who may have adopted and abandoned bows and arrows (Diamond 2005; but see Attenbrow et al. 2009 re Australia). Riede (2008) presented archaeological evidence for the demise of bow-and-arrow technology in a European context. According to him, the eruption of the Laacher See volcano at *15 ka, in present-day western Germany, had a dramatic impact on forager demography. It triggered archaeologically visible cultural change along the northern periphery of Late Glacial European settlement. In southern Scandinavia, these changes took the form of technological simplification – including the loss of bow-and-arrow technology. Examples are not limited to the Stone Age or to hunting technologies either; there are ample historical and ethnographical cases in point (Shennan 2001; Henrich 2004; Diamond 2005; Powell et al. 2009).

It is therefore not feasible to take for granted that once societies adopt useful (and seemingly advanced) technologies, they inevitably retain them until a more advanced

solution is found – ratcheting up (Fig. 12.3b) (e.g., Shea 2006; Lombard and Parsons 2011). Technological innovations must not only be acquired, they also have to be maintained across generations. Long-term maintenance, similar to invention, depends on many unpredictable factors. Apart from the physical environment, all societies go through social trends and changes in ideology. Sometimes such trends cause useless objects to become ‘valued’ or useful things to be provisionally ‘devalued’ (Diamond 2005; Hovers and Belfer-Cohen 2006). The fact that not all innovative technological trends necessarily continue seamlessly, may seem difficult to reconcile with common perceptions of cultural evolution that is frequently understood as accretive, progressive (Kuhn 2006), or ratchet-like. Earlier technological systems – for example, hand-delivered weaponry such as single component or composite spears – are often seen as incomplete or impoverished versions of later more complex systems such as spearthrower-and-dart or bow-and-arrow technology. According to this view, human cultural development occurred along a single trajectory, marked by major innovations or advances, and measured in terms of its distance from what is perceived to be ‘modern’ human behavior. This stance derives from early culture evolutionist discourse, and deviates from contemporary notions of cultural and behavioral evolution as historically contingent processes, based on random production and subsequent reduction of novelty (Kuhn 2006:117; also see Shea 2011).

The ratchet effect, which by definition allows for movement in one direction only (Fig. 12.3b), thus fails to explain human culture and behavior as documented in the historical and archaeological records. It is simply too rigid and rectilinear (Carniero 2003), to allow for highly developed human behavioral, cultural and cognitive flexibility and variability. Thus, there seem little reason for Stone Age archaeologists to persistently bind their explanatory theories to models of human behavioral evolution and variability that may not be germane, are outdated and/or too unilinear (Shea 2011), such as the Spencerian model of progression towards a specific, anticipated goal (Spencer 1896; Mesoudi 2008). Should the ratchet fail, few outcomes are possible – a complete standstill, a backwards slip or total collapse – resulting in explanations of behavioral, cognitive, cultural and/or technological stagnation, reversal, devolution or regression (e.g., Henshilwood 2005; McCall 2007; Mellars 2007). But, simplification or cultural change does not always translate into these concepts (Henrich 2004; Lombard and Parsons 2010, 2011). Humans

144 |

M. Lombard |

think, function and interact within a multi-directional and multi-leveled matrix (even if some aspects may at times represent a unilinear trend), and this is probably what we see reflected in our cultural records (Fig. 12.3d).

Or Is It Mountaineering?

To help explain what we observe archaeologically and historically, when it comes to human cultural, cognitive and behavioral evolution, the theoretical concept of a rugged fitness landscape is perhaps more fitting than that of the ratchet effect (Kuhn 2006; Lombard and Parsons 2011). Disparities in local cultural and technological change and variability probably represent a trend towards regional differentiation. It is likely that regional demarcations materialize in response to specific ecological conditions, demographic and social adjustments, raw material constraints, technological knowledge bases (Kuhn 2006), limits on energy, and time-budgeting factors (Shea and Sisk 2010). Transitions do not always represent shifts from one stable condition to another – as in the course of ratcheting. Phases are dynamic and variable, expressed by different groups in different behaviors and on different spatio-temporal scales (Fig. 12.3d) (Kuhn 2006). It should therefore come as no surprise that we see different kinds of trends over time and space, depending on prevailing variables.

A fitness landscape is a theoretical construct that reflects the influence of different factors on the fitness of a population. Higher points in this topographic landscape represent adaptive configurations of greater fitness than lower points (Kuhn 2006). In a simple landscape, all factors converge to create a single high peak – a single behavioral or physical phenotype that provides a most favorable adaptive solution to a wide range of problems, similar to a ratchet. In the simple fitness landscape scenario, selection will tend to drive populations towards this single peak from anywhere in the landscape. On the other hand, rugged fitness landscapes consist of many peaks of varying heights (Fig. 12.3d). The valleys separating peaks represent lower fitness adaptations (Kuhn 2006). In a complex topographic landscape, however, populations will tend to gravitate towards the peaks closest to their starting point, which may or may not be the highest peak in the landscape (Fig. 12.3d). Theory dictates that once a population has started their ascent of a particular fitness peak, it is difficult to shift to another (Kuhn 2006). Even moving to a peak that may provide greater fitness could be challenging as shifting between peaks would first involve a reduction in fitness. Yet, severe environmental or demographic change may dislodge a population from its existing summit allowing it to access another, possibly even higher peak (Kuhn 2006). In addition to climate and demography

such fitness displacements may also occur as a result of dramatic shifts or disruptions in the socio-cultural and/or ideological organization of a society (e.g., Hovers and Belfer-Cohen 2006; Lombard and Parsons 2011).

Viewed within this theoretical framework, it is conceivable that, for example, developing and using bow-and-arrow technology could have been one of many elements within a specific evolutionary trajectory of a specific group. Any, or a combination of many, variable/s could have forced or encouraged a shift in behavior and technology to a different fitness solution (Fig. 12.3d). Such a shift may require reduction in a population’s existing fitness repertoire to deal with challenges and regain momentum for attaining new fitness levels. At different points on the topography of human evolution, bow-and-arrow hunting may thus have been an element that sometimes remained intact, became redundant and re-invented (or not), depending on the technological and behavioral evolutionary trajectory of any specific society (Fig. 12.3d) (Lombard and Parsons 2011).

The archaeological and historical records indicate that there is a range of reasons that may force or inspire groups to move between the peaks on the fitness landscape. In the process they (we) have to overcome low-lying valleys, which may sometimes reflect periods of technological, organizational, social or ideological change and/or simplifi- cation. A modern-day example would be changing jobs, cities or countries in the hope of better prospects. A person or family may come from a relative secure social and economic environment, but for a while, they have to expose themselves to increased risk and reduced fitness levels (e.g., the loss of property or a social network) to reap the possible rewards of a different lifestyle.

Thinking about the evolution of human behavioral, cognitive and technological flexibility in terms of many individuals, groups or societies negotiating several rugged or complex fitness landscapes, with many peaks of various height and incline, more readily brings to mind the use of mountaineering gear than a ratchet. Mountaineering represents a flexible system, with both simple and complex equipment anchoring climbers to their existing fitness landscapes or situations, using a supple rope (Fig. 12.3d). In this scenario, a range of components/technologies/behaviors may be used or discarded, and ropes can be secured, detached, or reconnected in all directions, as and when needed. While it provides advanced flexibility, it also remains firmly anchored in what came before (similar to ideas about cumulative culture and the ratchet analogy), but, it is not rigid, and it does not depend entirely on what came earliest for its stability and/or strength (Fig. 12.3d). Thus, change, even in the case of simplification, does not automatically translate into a backwards slip or collapse – stagnation, reversal, devolution or regression – it probably signals a shift or adjustment in the evolutionary trajectory of a group.