Bordens Social Psychology (3rd ed)

.pdfChapter 2 The Social Self

the social comparison process by which we compare our own reactions, abilities, and attributes to others (Festinger, 1950). We do this because we need accurate information so that we may succeed. We need to know if we are good athletes or students or race car drivers so that we may make rational choices. Social comparison is a control device, because it makes our world more predictable.

A third source of information comes from the self-knowledge gained by observing our own behavior. Daryl Bem (1967) suggested that people really do not know why they do things, so they simply observe their behavior and assume that their motives were consistent with their behavior. Someone who rebels against authority may simply observe her behavior and conclude, “Well, I must be a rebel.” Therefore, we may obtain knowledge of our self simply by observing ourselves behave and then infer that our private beliefs must coincide with our public actions. Another method of knowing the self is through introspection, the act of examining our own thoughts and feelings. Introspection is a method we all use to understand ourselves, but there is evidence to suggest that we may get a somewhat biased picture of our own internal state. Thinking about our attitudes and the reasons we hold them can sometimes be disruptive and confusing (Wilson, Dunn, Kraft, & Lisle, 1989). More generally, the process of introspec- tion—of looking into our own mind, rather than just behaving—can have this effect. For example, if you are forced to think about why you like your romantic partner, you might find it disconcerting if you are not able to think of any good reasons why you are in this relationship. This doesnʼt mean that you donʼt have reasons, but they may not be accessible or easy to retrieve. Much depends on the strength of the relationship. If the relationship is not strong, thinking about the relationship could be disruptive because we might not think up many positive reasons in support of the relationship. If it is pretty strong, then reasoning might further strengthen it. The stronger our attitude or belief, the more likely that thinking about it will increase the consistency between the belief and our behavior (Fazio, 1986).

31

social comparison process A source of social knowledge involving how we compare our reactions, abilities, and attributes

to others.

introspection The act of examining our own thoughts and feelings to understand ourselves, which may yield a somewhat biased picture of our own internal state.

Personal Attributes and Self-Concept

Now that we have noted some of the methods we may use to form and gain access to our self-concept, letʼs see what is inside. What kind of information and feelings are contained in the self? First of all, the self-concept contains ideas and beliefs about personal attributes. A person may think of herself as female, American, young, smart, compassionate, the daughter of a single mother, a good basketball player, reasonably attractive, hot-tempered, artistic, patient, and a movie fan. All of these attributes and many more go into her self-concept.

Researchers investigated the self-concepts of American schoolchildren by asking them the following kinds of questions (McGuire & McGuire, 1988, p. 99):

•Tell us about yourself.

•Tell us what you are not.

•Tell us about school.

•Tell us about your family.

These open-ended probes revealed that children and adolescents often defined themselves by characteristics that were unique or distinctive. Participants who possessed a distinctive characteristic were much more likely to mention that attribute than were those who were less distinctive on that dimension (McGuire & McGuire, 1988).

personal attributes

An aspect of the self-concept involving the attributes we believe we have.

32

distinctiveness theory The theory suggesting that individuals think of themselves in terms of those attributes or

dimensions that make them different—rather than in terms of attributes they have in common with others.

autobiographical memory Memory for information relating to the self that plays a powerful role in recall of events.

Social Psychology

According to distinctiveness theory, people think of themselves in terms of those attributes or dimensions that make them different, that are distinctive, rather than in terms of attributes they have in common with others. People, for example, who are taller or shorter than others, or wear glasses, or are left-handed are likely to incorporate that characteristic into their self-concept.

People usually are aware of the attributes they have in common with other individuals. A male going to an all-male high school is aware that he is male. But being male may not be a defining part of his self-concept because everybody around him has that same characteristic. He will define himself by attributes that make him different from other males, such as being a debater or a football player. It may certainly be important in another social context, such as when taking part in a debate about changing gender roles.

People who belong to nondominant or minority groups are more likely to include their gender, ethnicity, or other identity in their self-concept than are those in dominant, majority groups (e.g., white male). Among the schoolchildren in the study (McGuire & McGuire, 1988), boys who lived in households that were predominantly female mentioned their gender more often, as did girls who lived in households that were predominately male.

Of course, not all knowledge about the self is conscious simultaneously. At any given time, we tend to be aware of only parts of our overall self-concept. This working self-concept varies depending on the nature of the social situation and how we feel at that moment (Markus & Gnawers, 1986). So when we are depressed, our working selfconcept would be likely to include all those thoughts about ourselves that have to do with failure or negative traits.

Although the self-concept is relatively stable, the notion of a working self-concept suggests that the self can vary from one situation to another (Kunda, 1999). For example, as the late Ziva Kunda (1999) pointed out, if you are shy but are asked to give examples of when you were very outgoing, at least momentarily you might feel less shy than usual. However, the ease with which the self may change may depend on how self-knowledge is organized and how important the behavior is.

The Self and Memory

In addition to personal attributes, the self-concept contains memories, the basis for knowledge about oneself. The self is concerned with maintaining positive self-feelings, thoughts, and evaluations. One way it does this is by influencing memory. Anthony Greenwald (1980) suggested that the self acts as a kind of unconscious monitor that enables people to avoid disquieting or distressing information. The self demands that we preserve what we have, especially that which makes us feel good about ourselves.

According to Greenwald, the self employs biases that work somewhat like the mindcontrol techniques used in totalitarian countries. In such countries, the government controls information and interpretations of events so that the leadership is never threatened. Similarly, we try to control the thoughts and memories we have about ourselves. The self is totalitarian in the sense that it records our good behaviors and ignores our unsavory ones, or at least rationalizes them away. The self is a personal historian, observing and recording information about the self—especially the information that makes us look good. Like a totalitarian government, Greenwald claims, the self tends to see itself as the origin of all positive things and to deny that it has ever done anything bad.

Is it true, as Greenwald predicted, that the self is a kind of filter that makes us feel good by gathering self-serving information and discarding information that discomfits us? The study of autobiographical memory—memory for information relating

Chapter 2 The Social Self |

33 |

to self—shows that the self does indeed play a powerful role in the recall of events (Woike, Gerskovich, Piorkowski, & Polo, 1999). The self is an especially powerful memory system, because events and attributes stored in the self have many associations (Greenwald & Banaji, 1989). Letʼs say, for example, that you are asked to recall whether you have done anything in your life that exemplifies a trait such as honesty or creativity. A search of your self-memory system perhaps would conjure up a recent event in which you devised a creative solution to a problem. The memory of that event might trigger similar memories from earlier periods in your history. You probably would be able to generate a flood of such memories.

Most people take only about 2 seconds to answer questions about their traits (Klein, Loftus, & Plog, 1992). This is because we have a kind of summary knowledge of our self-traits, especially the most obvious ones. Such a handy summary makes it harder to access memories that conflict with our positive self-concept, however. As noted earlier, memories that match a personʼs self-concept are recalled more easily than those that clash with that concept (Neimeyer & Rareshide, 1991). If you perceive yourself as an honest person, you will have trouble digging up memories in which you have behaved dishonestly.

A research study of social memory of everyday life among college students bore out these findings (Skowronski, Betz, Thompson, & Shannon, 1991). Participants were asked to keep two diaries: In one, they recorded events that occurred in their own lives, and in the other, they recorded events that occurred in the life of a close relative or friend, someone they saw on a daily basis. The students had to ask the consent of the other person, and they recorded the events discreetly. Participants made entries in the diaries for self and other for roughly 10 weeks, the length of the academic quarter. At the end of the quarter, the participants took a memory test on the events recorded in the two diaries. They were presented with the recorded events from the diaries in a random order and were asked to indicate how well they remembered the event, the date it occurred, and whether it was a unique episode.

The researchers found that participants recalled recent events more quickly than earlier ones, with faster retrieval of the oldest episodes than of those in the middle. They also found that pleasant events were recalled better than unpleasant ones, and extreme events, pleasant and unpleasant, were recalled better than neutral episodes. Pleasant events that especially fit the personʼs self-concept were most easily recalled. The self, then, monitors our experiences, processing information in ways that make us look good to ourselves. We interpret, organize, and remember interactions and events in self-serving ways, recalling primarily pleasant, self-relevant events that fit our selfconcept. Obviously, this built-in bias influences the manner in which we understand our social world and how we interact with other people. Without realizing it, we are continually constructing a view of the world that is skewed in our favor.

Emotions and Autobiographical Memories Some of you may be thinking as you read this, “These findings donʼt square with what happens to me when I think about my past.” It is true that you donʼt always retrieve memories that are positive, pleasant, or bolster good feelings. Indeed, sometimes the precise opposite is true. McFarland and Buehler (1998) examined how negative moods affect autobiographical memory. Generally, the memories you may recall seem to fit the mood that you are in. The explanation for this mood-congruence recall is that our mood makes it more likely that we will find memories of events that fit that mood: positive mood, positive recall; negative mood, negative recall. People who experience lots of negative moods can

34 Social Psychology

enter into a self-defeating cycle wherein their negative moods prime or key negative memories that in turn make the individual even more sad or depressed.

Why do some people in negative moods perpetuate that mood and others make themselves feel better? It appears that the approach to how we retrieve these memories is the key (Lyubomirsky, Caldwell, & Nolen-Hoeksema, 1998). If you adopt a focused reflective attitude, which means that you may admit that you failed at this task, you explore the nature of why you feel bad and work to regulate that mood. This is in contrast to people who ruminate over their moods. That is, they focus neurotically and passively on negative events and feelings (McFarland & Buehler, 1998).

Of course, over our lifetimes our experiences may very well alter, sometimes dramatically, our sense of ourselves. If this change is significant, we may look back and wonder if we are in fact the same person we once were. William James (1890), the renowned 19th-century psychologist and philosopher, observed that the self was both a “knower” (“I”) and an object (“me”). For college students, the transition from high school to university may produce a conflict between the personʼs current sense of self and that other person that existed before the transition: “I am not the same person that I was 2 years ago.”

Psychologists Lisa Libby and Richard Eibach (2002) investigated what happened when people thought about behaviors that conflicted with their current self-concept. When this happens, individuals refer to their “old self” in the third person, as if it were an object no longer part of the psyche. Autobiographical memory, then, is not static, but may be altered by our current self-concept. For example, someone who recalls that he was a chronic overeater in the past may transform that bit of autobiographical memory into motivation not to overindulge at this Thanksgivingʼs meal (Libby & Eibach, 2002). Major life changes often require that people disengage from their past. Imagine, for example, “born again” religious experiences, or surviving a deadly cancer, or a divorce and the resultant radical change in lifestyle. These events can make people “disidentify” with their autobiographical memories of their past selves (Libby & Eibach, 2002). It is not as if we create a brand-new self, but rather we place the old one in a kind of cold storage.

Religion and the Self

Peers, school experiences, and involvement in religious activities and institutions may have profound effects on self-knowledge. As we suggested in the previous section, the self-concept is not an unchanging vault of personal information but is powerfully influenced by social, situational, and cultural forces. We saw the influence of the church on the life of James Carroll, the priest. In novelist Carrollʼs books after he left the priesthood, we can see that the church still has an enormous influence on his thinking and his view of himself and the world.

Bruce E. Blaine and his coworkers investigated the impact of religious belief on self-concept (Blaine, Trivedi, & Eshleman, 1998). Blaine pointed out that religion ought to be a powerful influence on the self-concepts of believers. Religious beliefs typically set standards for character and behavior, emphasizing positive behaviors and exhorting believers to refrain from negative ones. Blaine found that individuals who indicated that they maintained religious beliefs (Protestant, Catholic, or Jewish) provided more positive and certain self-descriptions. These positive self-descriptions were not limited in Blaineʼs study to religious spheres solely but were also related to positive self-descriptions in the individualsʼwork and social lives.

Chapter 2 The Social Self |

35 |

Blaine and his colleagues (1998) suggested several reasons for these findings. The first is that religious teachings may have clear relevance to the business world to the extent that people who hold religious beliefs actually apply them to other life activities. As one example, Blaine notes the Jewish Torah warns that interest ought not be charged on goods sold to needy countrymen. Religion also may be an organizing principle for the self-concept and thereby embrace all facets of life.

The Self: The Influence of Groups and Culture

Thus far we have focused on the individual self, that part of the self that refers to our self-knowledge, including our private thoughts and evaluations of who and what we are. But as we saw in James Carrollʼs life, the groups to which we belong and the culture in which we live play crucial roles in sculpting our self-concept.

The collective self is that part of our self-concept that comes from our membership in groups. This collective self is reflected in thoughts such as, “In my family I am considered the responsible, studious one.” It reflects the evaluation of the self by important and specific groups to which the person belongs (Greenwald & Pratkanis, 1984). Basic research on groups shows that the groups we belong to have a strong influence on selfconcept (Gaertner, Sedikides, & Graetz, 1999). Our behavior is often changed by what other group members demand of us.

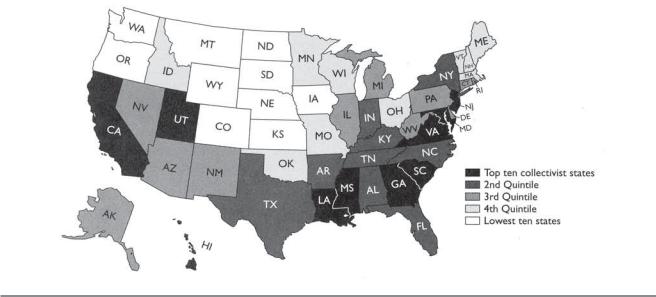

These two representations, the individual and the collective selves, do not occupy equal space and influence in the self-concept. The relative importance of each component of the self for an individual is determined in large part by the culture in which the person lives. In some cultures, the individual self is dominant. Cultures that emphasize individual striving and achievement—societies that are concerned with people “finding themselves”—produce individuals in which the private self is highly complex, containing many traits and beliefs. Other cultures may emphasize specific groups, such as family or religious community, and therefore the collective self is primary. Collectivist societies show a pattern of close links among individuals who define themselves as interdependent members of groups such as family, coworkers, and social groups (Vandello & Cohen, 1999). However, even within societies, the degree of collectivism may vary. Vandello and Cohen (1999) argued that collectivist tendencies in the United States would be highest in the Deep South, because that region still maintains a strong regional identity. Vandello and Cohen also thought that the greatest individualistic tendencies would be found in the West and mountain states. Figure 2.1 shows a map that identifies regional differences in collectivism. You can see that Vandello and Cohenʼs predictions were confirmed. Note that the states with the highest collectivism scores contain either many different cultures (e.g., Hawaii) or a strong and dominant religion (e.g., Utah).

One way to determine whether the individual or collective self is the dominant representation of who we are is to observe what occurs when one or another of these images of the self is threatened. Is a threat to the individual self more or less menacing than a threat to our collective self? If the status of the important groups to which we belong is threatened, is this more upsetting to us than if our individual, personal self is under attack?

In a series of experiments, Gaertner, Sedikides, and Graetz (1999) tried to answer these questions by comparing individualsʼresponses to threats to the collective or individual self. For example, in one study, women at a university were given a psychological test and were told either that they personally had not done very well on the test or that an important group to which they belong (women at the university) had not done well. Similar procedures were used in other experiments. Gaertner and his colleagues found

individual self The part of the self that refers to our self-knowledge, including our private thoughts and evaluations of who and what we are.

collective self The part of our self-concept that comes from our membership in groups.

36 |

Social Psychology |

Figure 2.1 Map of the United States showing regional patterns of collectivism.

From Vandello and Cohen (1999).

that compared to a threat to the collective self, a threat to the individual self resulted in the perception that the threat was more severe, a more negative mood, more anger, and the participantsʼdenial of the accuracy or validity of the test or source of the threat.

The results suggest that the individual self is primary, and the collective self is less so. Of course, this does not mean that the collective self is not crucial. It and our group memberships provide protection and financial and social rewards. But all things being equal, it appears that, in the United States, our individual self is more important to us than our collective self.

Who Am I? The Influence of Culture on Self-Concept

Nothing, it seems, could be more personal and individual than how we answer the question, Who am I? But as it turns out, our answer is powerfully shaped by the culture in which we grew up and developed our self-concept. As we have suggested, some cultures place more emphasis on the uniqueness of the individual—the private self— whereas others focus on how the individual is connected to important others—the collective self.

In a culture that emphasizes the collective self, such as Japan, individuals are more likely to define themselves in terms of meeting the expectations of others rather than of fulfilling their own private needs. In fact, if you asked Japanese participants to answer the question, Who am I? (a common technique for investigating self-concept), you would find that they give many more social responses (“I am an employee at X”) than do Americans (Cousins, 1989). In contrast, Americans are more likely to emphasize the content of the individual (private) self, defining themselves with such statements as “I am strong-willed.” The Japanese view themselves as part of a social context, whereas Americans tend to assume they have a self that is less dependent on any set of social relations (Cousins, 1989; Ross & Nisbett, 1991).

Individuals in cultures that emphasize the collective self are also less likely to view themselves as the focus of attention in social interactions (Markus & Kitayama, 1991; Ross & Nisbett, 1991). Japanese appear to view their peers, rather than themselves, as the focus of attention. Consequently, social interactions in Japan are quite different from those in a society such as the United States.

Chapter 2 The Social Self |

37 |

Individual-self societies emphasize self-fulfillment at the expense of communal relationships; collective-self societies are more concerned with meeting shared obligations and helping others. In Haiti, for example, where the culture emphasizes the collective self, people are willing to share houses and food with relatives and friends for long periods of time.

Of course, no matter the dominant sense of self in each culture, sometimes situational factors will determine which self is dominant. Gardner, Gabriel, and Lee (1999) showed that the individual self may be temporarily more dominant in a collectivist culture when people are focused on personal issues—say, oneʼs intelligence or oneʼs goals in life. Similarly, people who live in an individualistic culture may temporarily focus on collectivist factors when confronted by issues involving group belongingness (“I am a member of Kappa Kappa Gamma”).

However, whatever the effects of temporary situational factors, obviously, the thoughts and traits that make up the core of the self of a Japanese or Haitian person are likely to differ from the content of the self of an American. We would expect many more individual attributes to be part of an American self-concept. Japanese or Haitian individuals would probably emphasize attributes that reflect their similarities with others, whereas Americans are more likely to emphasize attributes that make them different from other people.

This tendency to emphasize attributes that make an individual stand out in American society and to blend in and not be conspicuous in Japanese society may very well be due to historical and cultural processes that affect how individuals behave. For example, in the United States, our sense of well-being, of being happy or pleased with ourselves, depends to a great extent on whether we are seen as better—more accomplished, perhaps richer— than other people. But, Shinobu Kitayama, a Japanese social psychologist familiar with the United States, suggests that a sense of well-being in Japan depends less on attributes that make individuals different from others and more on correcting shortcomings and deficits (Kitayama, Markus, Matsumoto, & Norasakkunkit, 1997). Research shows that the psychological and physical well-being of Japanese persons can be predicted quite accurately from the lack of negative characteristics and not from the presence of positive attributes (Kitayama et al., 1997). In the United States, in contrast, how positive we feel about ourselves is directly related to our sense of personal well-being (Diener & Diener, 1995). So these social psychological aspects of self-representations—the individual and the collective selves—are caused by historical forces that emphasized individuality in the United States and group harmony in Japan.

We see in this example both the pervasive role of the self-concept in directing behavior and the widespread role of culture in determining ideas about the self. The self-concept is not just a private, personal construct; culture plays a part in shaping the individualʼs deepest levels of personal knowledge.

Organizing Knowledge: Self-Schemas

Whatever the culture one lives in, people donʼt think of themselves as just chaotic masses of attributes and memories. Instead, they arrange knowledge and information about themselves and their attributes into self-schemas (Markus, 1977; Markus & Zajonc, 1985). A schema is an organized set of related cognitions—bits of knowledge and information—about a particular person, event, or experience. A self-schema is an arrangement of information, thoughts, and feelings about ourselves, including information about our gender, age, race or ethnicity, occupation, social roles, physical attractiveness, intelligence, talents, and so on. People have many different self-schemas for the different areas of life activities.

self-schemas

Self-conceptions that guide us in ordering and directing our behavior involving how we represent our thoughts and feelings about our experiences in a particular area of life.

38 |

Social Psychology |

sexual self-schema

How we think about the sexual aspects of the self, derived from past sexual knowledge and experience, and which guides future sexual activity.

Self-schemas serve a very important function: They organize our self-related experiences so that we can respond quickly and effectively in social situations. They help us interpret situations, and they guide our behavior. Schemas also help us understand new events (Scheier & Carver, 1988). You may have a self-schema about how you act in an emergency, for example. From past experience and from your ideals and expectations about yourself, you may believe that you are a person who stays calm, acts responsibly, and takes care of others, or one who panics and has to be taken care of by others. These beliefs about yourself influence your behavior when an emergency arises in the future. Or perhaps you have a self-schema about being a runner. When you hear people talking about keeping fit or eating the right foods, you know what they are talking about and how it relates to you. In these ways, self-schemas contribute to our sense of control over our social world.

Self-schemas lend order to our past experiences as well. They guide what we encode (place) into memory and influence how we organize and store that memory. Memories that match our self-schemas are recalled more easily than are those that do not (Neimeyer & Rareshide, 1991). Self-schemas also influence how we think we will behave in the future. A person who thinks of himself as socially awkward, for example, may behave inappropriately in social situations. And based on his behavior in the past, he expects to behave inappropriately in future social situations.

People tend to have elaborate schemas about areas of life that are important to their self-concepts. Markus (1977) observed that people may be either schematic or aschematic with respect to various attributes that are in the self-concept. The term schematic means that the individual has an organized self-schema in an activity that the individual rates as important. In other areas of life, those that are not important to us or that may not even exist for us, people are said to be aschematic. That is, they do not have an organized self-schema in that domain.

Sexuality and Self-Schemas

Sexuality is clearly a fundamental behavior, and therefore we expect people to have sexual self-schemas of varying degrees of organization. A sexual self-schema refers to how we think about the sexual aspects of the self. Sexual schemas are derived from past sexual knowledge and experience and, as all schemas do, they guide our future (sexual) activity. Cyranowski and Andersen (1998) studied the sexual self-schemas of university women and found that four different schemas emerged. Women who were schematic—that is, had well-developed schemas—displayed either positive or negative schemas. These positive and negative schemas reflected their individual past sexual history as well as their current sexual activity. As the sexual schema graph shows, positive-schema women had more previous sexual relationships (Figure 2.2) and scored higher measures of passionate attachment to their partners (Figure 2.3). These women were more likely to be in a current sexual relationship. Negative-sexual-schema women displayed an avoidance of intimacy and passion and were much more anxious about sexual activity.

Some women had both negative and positive aspects to their self-schemas, and they were labeled co-schematic. Whereas co-schematic women see themselves as open, passionate, and romantic (as do the positive-schema women), they differ from the positiveschema women in that they hold negative self-views, and this leads to anxieties about being rejected or abandoned by their partners.

Chapter 2 The Social Self |

39 |

Figure 2.2 The relationship between an individual’s sexual schema and the number of his or her first relationships.

Based on data from Cryanowski and

Anderson (1998).

Figure 2.3 The relationship between an individual’s sexual schema and his or her passionate love score.

Based on data from Cryanowski and

Anderson (1998).

Aschematic women, like negative-schema women, have fewer romantic attachments, experience less passionate emotions about love, and avoid emotional intimacy. Aschematic women tend to avoid sexual situations and display anxiety about sex. A major difference between aschematic women and negative-schema women is that aschematic women do not have negative self-views. They are just less interested in sexual activity. Table 2.1 summarizes these findings.

Whereas women express sexual self-schemas that fit roughly into categories, menʼs sexual self-schemas appear to flow along a continuum, ranging from highly schematic to aschematic (Andersen, Cyranowski, & Espindle, 1999). Men who are schematic have

40 |

Social Psychology |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Table 2.1 Sexual Schemas and Sexual Behaviors |

|

||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Schematic |

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Sexual Behaviors |

Positive |

Negative |

Co-Schematic |

Aschematic |

|

|

Previous sex |

|

|

|

|

|

|

experiences |

Many |

Few |

Moderate |

Few |

|

|

Passionate |

High |

Low |

High |

Low |

|

|

Intimacy |

High |

Low |

Low |

Low |

|

|

Anxiety |

Low |

High |

High |

High |

|

|

Self-views |

Positive |

Negative |

Negative |

Moderate |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

sexual schemas that reflect strong emotions of passion and love, attributes shared with positive-schematic women. However, these men see themselves as strong and aggressive, with liberal sexual attitudes (Andersen et al., 1999). Schematic men lead varied sexual lives, may engage in quite casual sex, but are also capable of strong attachments. On the other end of the scale, we find aschematic men, who lead quite narrow sexual lives and have few if any sexual partners.

The more varied and complex our self is, the more self-schemas we will have. We can see that men and women have sexual self-schemas of varying degrees of organization, and these schemas reflect their sexual past and guide their current (and future) sexual behavior. These cognitive representations or self-schemas reflect both the importance of the behavior represented and the emotional tone of the behavior.

People differ in the number of attributes, memories, and self-schemas that are part of their self-concept. Some people have highly complex selves, others much less complex. Self-complexity is important in influencing how people react to the good and bad events in life. Someone who is, say, an engineer, an opera lover, a mother, and an artist can absorb a blow to one of her selves without much damage to her overall self-concept (Linville, 1985, 1987). If her latest artistic endeavors meet unfavorable reviews, this womanʼs sense of self is buffered by the fact that there is much more to her than being an artist. She is still a mother, an engineer, an opera lover, and much more. People who are low in self-complexity may be devastated by negative events, because there is little else to act as a buffer.

self-esteem An individual’s evaluation of the self, which can be positive or negative.

Self-Esteem: Evaluating the Self

The self is more than a knowledge structure. The self also has a larger sense of our overall worth, a component that consists of both positive and negative self-evaluations. This is known as self-esteem. We evaluate, judge, and have feelings about ourselves. Some people possess high self-esteem: They regard themselves highly and are generally pleased with who they are. Others have low self-esteem, feel less worthy and good, and may even feel that they are failures and incompetent.

Self-esteem is affected both by our ideas about how we are measuring up to our own standards and by our ability to control our sense of self in interactions with others. Both these processes—one primarily internal, the other primarily external—have important repercussions on our feelings about ourselves.