Thompson Work Organisations A Critical Introduction (3rd ed)

.pdf

14 Understanding Organisational

Behaviour: Issues and Agendas

The purpose of this chapter is to explore how psychology approaches issues of organisational behaviour: what is the mainstream agenda, what are its limitations and what alternative approaches might be useful? We will not survey industrial/organisational psychology as a whole (for a good account see Hollway, 1991); rather we will use historical and contemporary examples to explore what kind of knowledge organisational psychology produces. Our argument is that while there is much of value, mainstream approaches tend to offer a fragmented, partial account of the human condition, and moreover, one that is frequently distorted by a managerial agenda.

In a review of the ‘discipline’ of organisational psychology as a professional practice, Blackler describes it as follows:

The subject ‘organisational psychology’ can legitimately be understood to include all aspects of behaviour in organisations that may be studied from a psychological point of view. By common usage, however, the term is normally used to refer to applied social psychological studies of organisation. Important areas of practical and theoretical concern have included motivation, attitudes and job satisfaction, job and organisation design, interpersonal and group behaviour, leadership studies, approaches to participation and industrial democracy, conflict, decision-making, and the planning of change. (Blackler, 1982: 203)

This is by no means exhaustive of the work undertaken by organisational psychologists. Topics could be added from those more usually associated with occupational psychology such as selection, placement and counselling. If we ask the question, ‘what is the study of OB about?’, then as a subject it initially establishes a territory via which we can generate a list of topics as above. But such a list is not very helpful in understanding the distinctive character of the discipline. To do this, it is useful to begin from where it actually comes from.

Technologies of regulation?

Historically the subject has manifested a problem-centred approach dealing with the major perceived difficulties of organisational society at the time:

Industrial Psychology thus covers a wide field. It deals with the human, as contrasted with the mechanical and economic aspects of labour. Its chief aim is to reduce needless effort and irritation and to increase interest and attention throughout the workers in industry. (C. S. Myers, 1926: 11)

In a similar vein, Hollway (1991: 4–5) cites Alec Roger in the 1950s as giving a neat

214 • W O R K O R G A N I S AT I O N S

definition of the paradigm for occupational/industrial psychology as ‘Fitting the man to the job and the job to the man’, (FMJ/FJM). The issue here is one of the quality and integrity of the psychological practice and knowledge applied in the area, and the FMJ/FJM paradigm gives us a client-centred definition which from the start has given a technical orientation to work in the area. Such a definition relies heavily on the notion of a value-neutral, objective science that is independent of the power relations in the organisations and societies within which it is practised. The reality is, of course, that both power and knowledge are not singular, unitary or completely objective. Even a person believing he or she is a value-free carrier of fully objective scientific knowledge has to utilise and exercise that knowledge in the real world, and the one thing we do know is that power relations in organisations are seldom, if ever, completely equitable.

Without such awareness, new practical and theoretical knowledges from the repertoire of organisational behaviour can function as technologies of regulation, used to control and discipline employees. Such practices were inherent in the origins and early development of the sub-discipline of industrial psychology. In the first two decades of this century, employers drew on the variety of psychological theories on offer (Bendix, 1956: 200–1). For example, behaviourism’s orientation towards ‘human engineering’ was a particularly useful source of advice for managers seeking to manipulate environmental stimuli in the form of penalties and incentives, in order to produce appropriate worker responses. At the same time, rival schools such as instinct psychology could suggest means of employers meeting ‘innate’ needs such as self-expression, which were being distorted by evil Bolsheviks and union organisers. Perhaps most practically, vocational psychology could provide a battery of tests and measurements for applications to selection and placement. It was in this latter sphere that industrial psychology really took off in the US, boosted by the extensive use of tests for intelligence and other factors during the war.

Psychology in industry had in fact begun in the area of advertising, but it soon shifted from manipulation of consumers to workers. Most concepts and techniques were extremely primitive, but psychologists such as Munsterberg promoted the idea that they could be applied to the ‘labour problem’. The accumulation of knowledge about individual differences provided the basis for a varied apparatus of testing and measurement techniques geared to vocational counselling, placement testing and job analysis, with suggested correlations between factors such as intelligence, personality and potential work performance. Munsterberg summed up the general aim as finding ‘those personalities which by their mental qualities are especially fit for a particular kind of economic work’ (quoted in Baritz, 1960: 3). There was a widespread tendency to claim bogus relationships between national or racial characteristics and suitability for jobs (Kamin: 1979). In Britain, organisational psychology was relatively isolated from its American cousin. The National Institute of Industrial Psychology, founded under the leadership of Charles Myers in 1921, took a painstaking and broader interest in the related issues of training, rest, monotony and fatigue at work (see quote above and Hollway, 1991, for an analytic account of this venture). But even here consultancy pressures dictated programmes of vocational guidance, selection and testing.

It was these kinds of development that led Baritz (1960) to develop his famous analysis of psychologists and other industrial social scientists as servants of power. The science of behaviour was seen as giving management ‘a slick new approach to its

U N D E R S TA N D I N G O R G A N I S AT I O N A L B E H AV I O U R : I S S U E S A N D A G E N D A S • 2 1 5

problems of control’ (1960: 209). Included in the ‘bag of schemes’ were attitude surveys, selection devices, motivation studies, counselling and role-playing. Events in the 1930s Hawthorne studies, discussed in Chapter 4, were a particularly powerful confirmation of the social engineering role that could be played by social scientists, in this case under the framework of human relations theory. Those kinds of superficial and manipulatory practice are still being recycled today. For example, the reaction to objective problems that employees face in their work, recognised in the modern stress research literature, has led to the astonishingly innovative introduction of employee counselling programmes! Baritz’s great insight was to recognise that the service provided by social scientists to industry meant that ‘control need no longer be imposed. It can be encouraged to come from within.’ Workers could be manipulated to internalise the very ideologies and practices that ensured their domination.

A perfect modern example of this is the role played by industrial psychologists in some of the new human resource management techniques. The American writer Grenier (1988) worked as part of a team hired by Johnson and Johnson, the medical products company, to create the required conditions for the setting up of a new plant on a greenfield site in New Mexico. This involved many of the elements discussed in Chapters 11 and 12: quality circles and semi-autonomous work teams, status and symbolic harmonisation of conditions, extensive socialisation into a corporate culture facilitated by psychological testing at the selection and hiring stage. None of this of course is necessarily negative or manipulative, even the secret tape recordings of work team meetings to help identify success in fostering group identity and dynamics. But the hidden agenda of the whole project was a ‘union avoidance’ campaign, and this came to light when some of the workforce began an organising drive. The social psychologists became active and central participants in the struggle inside the heads of employees. All the supposedly innocent information collected became a means of screening workers and their attitudes. Team meetings in particular played an important role in identifying pro-union workers, and Grenier was asked to develop an index through which to rank workers in their degree of support. Grenier later publicly revealed this process and himself became subject to surveillance and intimidation.

Not all social scientists of course have been concerned with such manipulatory practices, and there has been a considerable amount of useful work done on employee satisfaction. The modern equivalents of Baritz’s servants of power are not necessarily ‘on the payroll’, but still have a tendency to accept managerial norms as the parameters of their activities. In the same way as the newspaper owner does not have to threaten journalists to toe the editorial line, mainstream behavioural scientists generally internalise controls, and largely unacknowledged self-censorship becomes the order of the day. In other words, the institutional relationship between the disciplines and their client groups remains a crucial problem.

Later, in developing out of industrial and human relations psychology in the 1950s and 1960s, organisational psychology brought to the study of work organisations an emphasis on descriptive and experimental research incorporated from social psychology. This was allied to the concern with applied psychology that had given impetus to industrial psychology in the early part of the century, and the human relations tradition discussed in earlier chapters. Later inputs to organisational psychology from areas such as socio-technical systems theory and operations research have further cemented the relationship of the subject with the interests of power groups in organisations.

216 • W O R K O R G A N I S AT I O N S

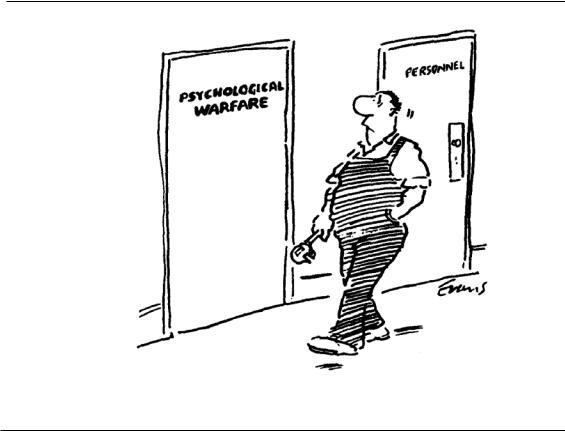

F I G U R E 1 4 . 1 ‘ P s y c h o l o g i c a l w a r f a r e’

Source: CAITS (1986) Flexibility, Who Needs It?, London, p. 34.

That the practitioners of organisational psychology and organisation theory are mainly located in such institutions as business schools, rather than in industry or psychology departments, also reinforces the conception of the subject as a discipline in its own right, with its own client groups and professional concerns. At the same time this distances them enough from their clients and subject matter to enable them to concentrate more on the theoretical understanding of organisations than was the case with the more strictly application-led industrial psychology. In turn, this enabled retention of much of the humanistic theoretical orientation derived from social psychology. Theoretical ideals of this nature do not, however, often survive exposure to the needs of the main client group. As with industrial psychology before it, this results in the subject becoming chiefly directed towards the practical needs of management. A humanistic perspective fully cognisant of the effects of organisational work on the interests and identities of employees is unlikely to promote harmonious relations with clients whose major tasks include the deployment and control of an organisation’s ‘human resources’. Nor would an organisational psychology that grounded its theory and practice in an understanding of the politics of production be likely to be in a position to fully give itself over to the demands of these clients. The upshot of all this is that the explanations, instruments and techniques developed from mainstream theories often function to sustain and implement a culture of domination in the workplace. Organisational psychology, though paradoxically informed by humanistic concerns, has both a role as an agent and a vested interest in mobilising the consent of organisational members.

U N D E R S TA N D I N G O R G A N I S AT I O N A L B E H AV I O U R : I S S U E S A N D A G E N D A S • 2 1 7

Topics and texts: subjects and subjectivities

Given the above discussion, it is not surprising that the areas from social psychology that have been enlisted into organisational psychology’s project of understanding human behaviour are often limited to those having functional utility. As we indicated above, texts tend to be presented under chapters or headings focusing on topics such as learning, perception and motivation, reflecting psychological explanations of individual personality; and topics such as leadership and group processes, which incorporate social-psychological explanations of interpersonal dynamics. However, topics in the sphere of aggression, affiliation and prejudice, which within social psychology are assumed to deal with influential determinants of human behaviour, have not been assimilated routinely into organisational psychology.

This is an odd separation, given that such factors may be expected to have at least some bearing on practices within organisations. The difference is largely that the latter set reflects areas of subjective experience which, although of importance to individuals and groups in organisations, are not of direct relevance to the production process, except insofar as they might interfere with it. Rather, the factors are treated as external to what is considered necessary and appropriate behaviour at work. Similarly, issues of discrimination, though a structural feature of organisational life, have long been marginalised and not constituted as significant objects of study. Aggression has been addressed obliquely in OB through the issue of organisational conflict, but the perspective used examined conflict, for example, as a problem to be resolved or avoided rather than to be understood as a possible consequence of inequalities of power and resources.

Since the first edition of this text, researchers have begun to look at issues of antisocial and aggressive behaviour in organisations in more detail (see Giacolone and Greenberg, 1997). They are producing evidence to show that factors such as downsizing, role diversity and increased reliance on part-timers are increasing the levels of emotional disturbance and aggression in the workplace (though the aggression is often indirect, passive and verbal, with the glaring exception of ‘going postal’). Likewise there have been moves of late to address issues such as discrimination in general OB texts, but this has generally been under headings such as managing diversity (see Chapter 10 and Weightman, 1999: 225–6). This, along with the issues of workplace bullying and ‘dealing with problem people’, is probably being addressed in the context of managing organisational liability to litigation on the basis of equal opportunities and employment legislation.

The competing mainstream explanations of psychological and social processes are treated in OB texts almost as if they were discrete accounts of human development and activity. Take an area such as learning (see Chapter 16) which must be integral to any account of psychological development; the mechanisms and processes of apparently mutually exclusive perspectives such as the cognitive and behaviourist models are categorised through the assumptions about human nature that underlie them. Thus we get the ‘models of man’ approach to OB, where theories are assessed through the assumptions they make and the implications of those assumptions for social behaviour. There is nothing intrinsically wrong with this as a method of analysis, but it does tend to reinforce the exclusivity of differing approaches, which are in fact no more than varying conceptions of the basic processes by which we all develop and negotiate our changing identities.

218 • W O R K O R G A N I S AT I O N S

We will return to the general limitations of the mainstream agenda in Part III. In its content, that agenda can be thought of as a journey through the processes by which individuals become social participants who perceive, learn and are motivated beings with individual personalities. Our intention here is to treat the mechanisms and processes identified by competing approaches as inputs to, rather than exclusive accounts of, this developmental process. This is because the fragmented treatment of subjectivity in OB means that the implied journey through an individual’s development into a social being never explicitly takes place.

Defining the ‘subjective factor’

While there is undoubted value in a topic-based approach, it tends, as we have noted, to miss out many issues and experiences, notably those of subjectivity and identity. The importance of the way that people feel about their selves and their organisational roles are demonstrated in the following:

I have a reputation for getting people’s backs up who work for me. I will help them if I consider they need it, but sometimes I give them the impression that I can’t be bothered. I prefer them to learn by looking for themselves. So I’m fairly abrupt and indifferent. I’m not worried if they like me but I do want their respect.

. . . I don’t like them to take advantage . . . they often say,‘Oh we can’t understand you, Allan, we try to be nice to you but you’re not nice back.’ I think there’s only one I’ve not made cry. . . . I don’t think I have to do the job. My job is to keep them as busy as possible. I’d rather me be bored than them, otherwise if you do bring work for them again, it just leads to moaning and groaning.You can’t keep all six happy at the same time.With some you can tell their monthly changes, even the other girls say so. Sometimes when they’re having a good chunner about the inspectors I have to impress on them that if it was not for the men, there’d be no jobs for them, if the blokes don’t go out and sell insurance. (Knights and Collinson, 1987: 158)

Socially produced identities are a central factor delineating people’s experience of work. As the authors of the Insco case study argue, Allan views his hierarchical position as a reflection of his own personal status and dignity. In his dealings with his female ‘subordinates’ he utilises a mixture of patronising humour, sarcasm and indifference in order to maintain a symbolic distance of authority and ‘motivate’ them to work independently. His proud boasts also indicate the significance of gender to his work identity.

The case itself addresses the gendered aspects of job segregation and the social construction of skill in the insurance industry where ‘Conventionally, the task is described in terms of an heroic drama in which intrepid and autonomous males stride out into the financial world and against the odds return with new business’. These ‘almost mystical perceptions’ of male skills are contrasted to the ‘internal staff of women clerks whose work is assumed to be dependent, supportive and secondary’ (1987: 148). Far from the aggressive instincts of the hunter, success in selling is seen to be dependent on the gendered interpersonal skills that are employed to maintain ‘exclusively male relationships’ with insurance agents. At the same time the devalued work of the female clerks is essential in the maintenance of long-term client support

U N D E R S TA N D I N G O R G A N I S AT I O N A L B E H AV I O U R : I S S U E S A N D A G E N D A S • 2 1 9

and after-sales service. Thus the success of the ‘heroic’ male is paradoxically dependant on the ‘stock of working knowledge’ possessed by the women, which allows them to maintain their own personalised telephone relations with clients. The unacknowledged and differentially rewarded ‘tacit skills’ employed in the administrative support role are ‘further emphasised when women also act as caring ego-masseurs or office wives for sales inspectors who sometimes return to the office dejected after unsuccessful appointments’ (1987: 150).

The continuation of such gendered job segregation is seen as being dependent on the continued acquiescence of the clerical staff to their subordination, even in conditions where Allan’s highly coercive approach generates a level of anxiety or frustrated resentment which is expressed in internal conflict, poor standards of work, indifference, disenchantment or even resignation. (Knights and Collinson, 1987: 168–9)

These reactions from the women underwrite the prejudicial attitudes used by the male managers to exclude the women from promotion to the sales force on the basis that they are ‘naturally’ unfit to handle such macho work. But such ‘reactions’ are not in fact problems in themselves; they are in effect the range of coping responses open to the women in that they themselves have internalised the view that they are unfit to be sales ‘reps’. By accepting the gendered definition of themselves they are limited to striving for personal material gain or ‘symbolic security expressed either in resignation, indifference or the search for future promotion within the clerical ranks’ (1987: 169). Such necessarily individualistic strategies are said merely to reproduce the contradictions of job segregation, and effectively to block any moves towards collective action that would challenge their institutionalised subordination.

Issues of identity raised in the Insco case are therefore central, but cannot be dealt with without concepts deriving from the study of structural processes such as organisational design, control strategies or the impact of wider social formations. But they in turn will be incomplete without reference to the factors surrounding the construction of the subjectivity and experience of those involved. Organisational psychology should allow us to enter these areas necessary for a fuller account of ‘organisational behaviour’. But as the discussions in Chapter 13 have begun to argue, the relation between organisational psychology and the subjective factor in the study of work organisations is by no means clear. Though organisational psychology and its practitioners might be expected to have a natural concern with the identities and subjective experience of participants, the range of issues and topics traditionally presented in the area do not consistently address these concepts. Explaining Allan’s relations to ‘his staff’ would thus be difficult using the theoretical models and concepts currently employed in introductory OB texts.

A further complicating factor here is the treatment of psychological knowledge in the literature. Hosking and Morley (1991) for example, give three types of dominant theoretical orientation. They cite Gordon Allport (1963) on the first two, which he terms the individualistic and culturalistic fallacies. The individualistic fallacy focuses on personal characteristics at the expense of cultural and contextual factors. The culturalistic fallacy turns this on its head to focus on social and situational forces at the expense of the person. The third approach they identify is the ‘more complicated without becoming more sophisticated’ (1991: 4) contingency approach, which is said

220 • W O R K O R G A N I S AT I O N S

to give weight to people and context but is merely a ‘statistical interaction’ between ‘inputs’ from person and context. This argument allows that an attempt has been made to take account of variables affecting individual and group psychology and action in organisations, but that it does not have an adequate account of the social interactions through which people produce their contexts and are shaped by them. Hosking and Morley (1991: 40–2) take this further in a critique of the top-down, entitative approaches (based on Meyer, 1985) that have dominated OB and HRM literatures. These are essentially reified perspectives relying on assumptions of the independence of person and organisation rather on their interdependence. Entitative approaches to persons focus on characteristics, traits and behaviours of individuals, while they treat organisations as entities in their own right with their own values and goals.

In an interesting commentary on such issues, Nord and Fox (1996) reviewed the linkages between organisation studies and psychological factors and processes. They found that the focus on the individual in organisational psychology has gradually moved away from the essentialist view of the individual found in approaches emphasising personality, motivation attitudes and so on. The shift has been towards ‘sociology, literature, communications and other disciplines consistent with a more macro conceptual orientation’ (1996: 170). This is somewhat at odds with the previous arguments of Henriques et al. (1984), whose view was that mainstream writings persist in an individual/society dualism. Even in attempts to provide accounts of how individualistic and culturalistic factors (cf. Allport and Hosking and Morley above) interact in shaping behaviour, there is still a tendency to come down on the side of explanations which emphasise biology and/or individual rationality as causative agents. Social and structural factors are tacitly acknowledged as having some effects, but these are seldom treated in an explicit fashion. They are generally reduced to the status of intervening variables that complicate the action of the individually based mechanisms and determinants of behaviour.

It may be that this dualism means that shifts from micro to macro OB, as Nord and Fox identify, can never produce a satisfactorily integrated meso level of analysis. This does not prevent us however from attempting to increase the level of articulation between contextualising and essentialist factors. Our approach to the ‘subjective factor’ in organisations tries to do this by focusing on the experience of people in work organisations through the common themes of subjectivity and identity. Both concepts present problems of interpretation, and there is considerable overlap in their usage. Our use of ‘subjectivity’ follows Henriques et al.’s (1984: 2–3) twofold definition (though see Pritchard, 1998 for a critique of our usage of this). First is the ‘condition of being subject’: the ways in which the individual is acted upon, and made subject to the structural and interpersonal processes at work in organisational life. Second, the ‘condition of being a subject’, possessing individuality and self-awareness. Thus the term encompasses the fundamentally contradictory experience of work and the subjective development and regulation of people’s ‘emotions, desires, fantasies, a sense of self’ (Banton et al., 1985: 44).

The concept of identity commonly involves the notion that there is an irreducible core of social and individual being that uniquely identifies each of us. Psychologically, identity variously incorporates concepts of self and self-esteem, structures of values, attitudes and beliefs, personality and associated traits. Sociologically, it includes concepts of self and of roles and reference groups. Lasch (1985: 31–2) notes a shift of meaning that does not admit a fixed or continuous identity, but a ‘minimal self’ which,

U N D E R S TA N D I N G O R G A N I S AT I O N A L B E H AV I O U R : I S S U E S A N D A G E N D A S • 2 2 1

because of our need for an ‘emotional equilibrium’, retreats to a ‘defensive core, armed against adversity’ (1985: 16).

Our usage then, incorporates the notion of self-aware and participative subjects, who maintain a valued part of their identity against the unpredictability of the external world, while being acted on and constrained by organisational ideologies and practices. These themes of subjectivity and identity are examined in the context of interrelated arguments, together providing a framework capable of addressing issues of structure, agency, individual action and experience. We are concerned to maintain a perspective rooted in a materialist conception of social production and existence. Capital, and management on its behalf, manipulate, direct and shape the identities of employees. This reflects the need to mobilise the consent and co-operation of workers in order that effective control may be maintained over the work process. We also maintain a focus on the development of identity in individuals and the reproduction and transformation of those identities in the context of work organisations. Individuals are not the passive recipients or objects of structural processes but are constructively engaged in the securing of identities (Knights and Willmott: 1985), and the development of capacities (Leonard, 1984). These, although influenced and shaped by organisational contexts and practices, are at the same time the unique products of each person’s history.

Conclusion

In any account of individual history and experience we need an appropriate starting point. Our problem in emphasising the thoroughgoing interdependence of concepts and issues in understanding behaviour in organisations, is that they should be treated in an integrated way. However, that is not the reality of standard discussion of behavioural issues. We have therefore maintained many of the traditional topic and conceptual divisions in order to engage with the existing forms of explanation. The final chapter on identity work acts to re-integrate our main themes and bring the conceptual threads together.

It is appropriate to begin with perception and its relations to attitudes and personality. In this way we can both make topics easier to identify and follow for the reader, at the same time as recognising that all of the psychological and relational processes we will discuss are dependent on the development of the perceptual processes which shape our view of the world.