Drewett_1999_Field_Archaeology

.pdf

WHAT IS AN ARCHAEOLOGICAL SITE? |

27 |

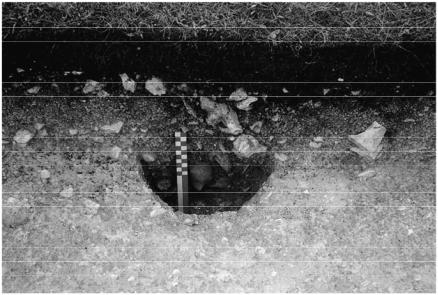

Figure 2.7 Effect of worm-sorting on shallow chalk downland soils (with possible posthole below).

Changes throughchemical actionareusuallymuch slower thanthenatural processesdescribed so far. Rainwater, even when not affected by industrial pollution to form acid rain , is slightly acid. This will affect particularly calcareous materials like lime mortar used in building. The mortar will be dissolved and wash away, perhaps finally resulting in the collapse of the structure. As the rainwater then passes into the soil it may take humic acids into solution from dead planttissues. This acid water will then affect buried artefacts and structures, dissolving away elements. These dissolved elements may survive in the soil and so could potentially be identified by archaeologists as chemical traces, but it is more likely that they will be washed out of the soil into rivers and finally the sea.

In addition to the chemical elements in soil moving down the profile and down slopes, soil itself is constantly on the move.As well as being cast onto the surface where worms are present, it is also constantly moving down slopes as the result of gravity, a process known as soil creep. The so-called sheep tracks often visible on slopes are little natural terraces caused by the gradual movement of soil downslope under the influence of gravity. These natural terraces gradually move downhill. Where there is a good vegetation cover, the movement is slow as the vegetation holds soil particles on the slope. Once the vegetation cover is broken, however, the movement can be quite rapid and it is often accentuated by water washing down the slope. The effect of this process can be seen at the bottom of fields where the moving soil may be trapped to form a lynchet, or in the bottom of valleys where depths of colluvium build up.Artefacts can

28 FIELD ARCHAEOLOGY

move down slopes as part of this process and be redeposited in the new soil deposits. As will be seen in Chapter Six, although a site on a hilltop or slope may vanish, its material remains may form an essential dating tool for the re-formed lynchet or valley-bottom deposits.

In addition to worms, insects and mites, most soils except those desiccated or waterloggedcontain fungi and bacteria.Anything organic in the soil will be affected by these organisms and, unless they have an inorganic element like calcium in bone or silica in some plants (phytoliths), will vanish as the result of fungal and bacterial action.

Growth of any vegetation on an archaeological site can affect the archaeology, changing or even destroying it. Standing masonry can be broken up by roots growing in cracks and forcing them apart. In the short term, roots and branches may hold masonry together, but when the plant dies and rots, then the masonry may collapse into the voids made by the rotting roots. If this happens above ground, the effect may be very visible and dramatic. Root action below ground is equally devastating, but may remain invisible until revealed by the field archaeologist excavating the site. Recent root action is usually straightforward to interpret, but ancient root action is not always so clear, particularly after worm-sorting and soil creep has affected the deposits. The broken-up wall may end up looking deliberately slighted by human action.

Natural earth movement can include both very minor shifting of surface layers or major movement as the result of earthquakes or volcanic action. Some deposits, like clay, have a tendency to slump down slopes, taking whatever is above with them down the slope. When this process detaches pieces of buildings it is often clear archaeologically. However, the slumping of deposits without features, like lithic scatters, is often more difficult to trace if the deposits have reconsolidated over time in their new location. Major earth movements like earthquakes usually create such devastation to archaeological deposits that their effect is easily traceable. The same applies to transformation as the result of volcanic action.

Two examples of abandonment

We will now look at a couple of examples of these processes in action on buildings, one masonry and the other timber. Naturally every example will be different, but the broad processes are often very similar with only detail varying from site to site.

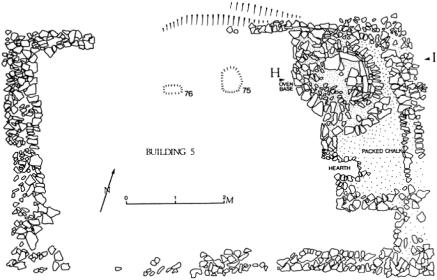

Masonry buildings can be constructed in a variety of ways. We will consider a small medieval farmhouse like Building 5 excavated at Kiln Combe, Bullock Down, Beachy Head, East Sussex, in England in 1976 (Drewett 1982a). This consisted of a small rectangular house 8.5 m × 5 m. It was constructed by cutting a level platform into the hill slope. The walls were then constructed on this platform without the use of foundation trenches. The walls were made of local flint held together with lime mortar made from the local chalk. The structure would have been roofed with timber, holding thatch. The doorway was in the southern corner and inside was a large bread oven and smaller cooking hearth. Furniture would have includedwooden tables,

WHAT IS AN ARCHAEOLOGICAL SITE? |

29 |

Figure 2.8 Plan of a household unit. Medieval farmhouse, Bullock Down, East Sussex.

benches and beds. Grain was ground between quernstones, wool spun with spindle whorls, and food cooked in large sagging-based cooking pots.Asmall family, perhaps a couple with several children, lived in the house (Fig. 2.8).

At some stage during the sixteenth century, probably as a result of the increasing value of sheep, the tenants of the house were evicted. One can imagine the scene of a cart being loaded up with the few portable valuables owned by the family, perhaps the table and stools, clothes, knives and cooking pots. The house was then abandoned. Some artefacts like a small chalk spindle whorl were lost in the process. The large mayen lava quernstone was abandoned as it was already beginning to shatter through age, and the evicted tenants would not expect to need it in their new urban life. Some objects were therefore lost in the process of final abandonment of the site, while others were simply left where they were.

Given the somewhat isolated location of the farmstead, human scavenging of the site is unlikely, although roof timbers may have been taken away for use as firewood. It is more likely that the site was simply left to natural processes of destruction. The untended thatch would come adrift from the roof and be blown off or collapse into the structure. The roof timbers would rot and fall in, making the mortar in the walls vulnerable to wind, water and chemical action. This would finally result in collapse of the walls, a process which would protect the lowest course or two of the wall from further erosion. As the house was constructed on a slight platform cut into the hill slope, soil creeping down the slope would be caught on the platform, thus protecting the floor and footings of the house.

30 FIELD ARCHAEOLOGY

While used as part of sheep runs, the remains of the house were well protected under developing downland turf. With a decline in sheep, however, scrubby bushes grew on the site with roots breaking up the buried masonry. Rabbits burrowed among these roots as earthworms cast soil onto the surface. Finally the site was ploughed up during the Second World War to provide more food in southern Britain. The preserving terrace was being slowly ploughed away when archaeologists intervened in 1975 before the site was finally obliterated. Similar sites elsewhere survive only as a spread of rubble with a few potsherds and animal bones in the modern plough soil.

Some buildings are constructed entirely of organic materials which will survive only if waterloggedordesiccated.Amerindian(nativeAmerican)housesintheCaribbeanwereconstructed entirely of organic materials. The small structure excavated at Hillcrest, Barbados, is a good example of a simple Amerindian shelter (Drewett 1991). It was constructed by setting five wooden posts, which were probably linked with some sort of ring beam, into holes dug in the ground. The structure was probably roofed with plaited leaves (Roth 1970). Most activities took place outside this small shelter, including potting, spinning cotton, cooking and making conch-shell tools. Debris from these activities was spread around the outside of the structure. Virtually everything usable was taken when the site was deserted aroundAD 1400. The structure itself was left to natural transformation processes. The structure may have been demolished very rapidly by hurricane action. Even if this was not the case, tropical rain and wind would soon have removed the unattended roof material. This would have exposed the posts to rapid bacterial action in the warm, humid climate. The posts would have rotted first at ground level, and then fallen onto the damp earth to rot rapidly. Deposits within and around the hut structure would have been churned about in the soil through the action of digging land-crabs and rapidlygrowing tropical roots.

Every archaeological site is, therefore, the end-product of a wide range of transformation processes. These take place during the life of the site, then at the point of abandonment, and continue as ongoing processes both natural and cultural. Very rarely are archaeologists dealing with the intact remains of past activity. All remains are transformed in some way, and without recognizing these transformation processes archaeologists could totally misinterpret the nature of a deposit, or even a whole site.

CHAPTER THREE

Finding archaeological sites

Existing knowledge

Many archaeological sites have never been lost. The site may have been abandoned but it may remain clearly visible in the landscape even if, during much of its post-use life, it was not considered an archaeological site as such. Classic sites like Stonehenge, the Great Wall of China, or the Acropolis in Athens have always been known. This usually, but not always, includes the major sites in a region. In England, for example, few medieval masonry castles have been lost while most small peasant farmsteads of the same date have been lost. In general, but not always, small sites are more likely to have been lost than big ones. However, big ones may also have been lost to archaeologists, even if known to the local population.

Many Mayan sites lost to and then discovered by Western archaeologists were well known to local Amerindian populations. So there are sites known to everyone, those lost to archaeologists but known to local people, and then those lost to everyone until rediscovered, like the Lascaux caves. Local people remain a major source of information about sites known to them, even if this knowledge has not reached the archaeological record. Afarmer, for example, will know where there are bumps (burial mounds?) in his fields or where the plough hits masonry (a Roman villa?).

Knowledge also exists in the records of any previous archaeological work undertaken in the area. This may consist of vague references by an eighteenth-century explorer, or detailed records of a recent field project. Increasingly this sort of information is brought together to form some sort of local, regional or national record prepared by archaeologists working in the area, often as part of a statutory body like a county council in England or the National Parks Service in the USA. These Sites and Monuments Records provide ready access to existing knowledge.

In Britain an attempt was first made to set up a national record by establishing the Royal Commission on the Historical Monuments of England (RCHME) and its sister organizations in Wales and Scotland.These were established by royal warrants in 1908. The standard of recording was, however, so high that by 1990 only some 150,000 sites had been recorded, in contrast to the 300,000-plus sites recorded by county-based Sites and Monuments Records in the first ten years of life since they were established in the early 1970s.

31

32 FIELD ARCHAEOLOGY

The basic elements of a Sites and Monuments Record consist of a written record of each site, with an associated map locating it. With this there may, or may not, be a photographic record including ground or aerial photographs. The major fields of information required of the written record are:

1Unique reference number

2Administrative area

3Address

4Cartographic reference

5Type of site

6Date of site

7Condition of site

To this basic record more and more detail can be added, depending on resources and how the record is going to be used. In Britain it should be remembered that county-based Sites and Monuments Records are essentially part of the planning process rather than a straightforward academic research tool. The quality of many SMRs, however, enables them to be used in both ways. Associated with each written record is a map locating (if possible) the exact position of each site or find recorded. Often early discoveries were, however, recorded only to a general area like a town or parish rather than in a precise location.

The first Sites and Monuments Records at a county level in Britain were established in the early 1970s, in areas like Oxfordshire and Essex. These started life as maps with associated record cards, but as computers became more readily available in the 1980s most records were computerized. Generally this involved simply putting the record card text into a computer system where the data can be accessed and maintained by a database management system.

During the 1980s, when it became possible for computers to handle all types of data in digital form, including maps and photographs, systems were developed so that all elements of SMRs could be computerized. Such data can now be incorporated into a Geographic Information System (GIS). At its simplest level these systems enable maps, text and photographs to be managed together.AGIS can produce layers of information. For example it could contain a base topographical map, solid geology, surface geology, soils, current land use and then archaeological sites. Data can be separated or combined in many different ways. For example all Roman settlements above 200 m on clay soils in a given region could be identified on a map on the screen. Written and photographic data about these specific sites could then be called up.

Currently few areas of the world have information about known archaeological sites readily available on a GIS, but clearly where they are available, as in parts of Ireland (Synnott 1996), this is where existing knowledge is most readily accessible. If no Sites and Monuments Record in any form is available, then existing knowledge will have to be searched for rather in the way the data for SMRs was originally gathered. This involves firstly a literature search of books and journals. In Britain most counties have a county archaeological society, many of which have

FINDING ARCHAEOLOGICAL SITES |

33 |

published an annual volume for a hundred years or more. The SussexArchaeological Society, for example, published its 134th volume on the archaeology and history of Sussex in 1996. These volumes formed the basis of the Sites and Monuments Records in the counties of West and East Sussex.

Secondly, existingknowledgemay survive inanunpublished form, like collections of artefacts in museums. Depending on how and when these data were collected, they may have more or less precise information about the location of the finds. Unfortunately, in the past, archaeological collections often moved well away from their place of discovery. One of the largest collections of neolithic flint axes from East Sussex, England, for example, was bought early in this century by the Royal Ontario Museum in Canada. Existing knowledge is therefore only as good as your ability to locate it.

Finally, existing knowledge is often stored in the heads of local people, and particularly local archaeologists, both professional and amateur. Farmers are often a major source of archaeological information although only if approached in the right way, as many see archaeology, and particularly archaeologists, as a potential threat to their use of their land. Often, however, archaeologists who have previously worked in the area but have failed to publish their results are more of a problem. Knowledge exists only when it is available!

Documents

Archaeologists working in historic periods will use documents as one of their main sources for the location of archaeological sites. Documents must, however, always be treated with caution. The fact that surviving fifteenth-century documents for a region made no mention of settlements in a particular area does not necessarily mean that there were none. The initial reason for the production of the document must always be considered, and whether the absence of information is simply because relevant documents have been lost.

Documentary evidence can be very detailed and specific, or very generalized, or both. Documents can also originate from within a community or be observations from an outsider looking in. The motives of the observer must always be assessed. Christopher Columbus srecord of prehistoric people in the Caribbean presents many of the classic problems associated with the use of documents produced by an observer looking into another community. Firstly, what is generally known as The journal of Christopher Columbus is an abstract made by the Dominican historian Bartolomé de las Casas, probably from a copy (now lost) made by two scribes from the original manuscript (also lost). Whether the scribes transcribed the document correctly, and what Bartolomé de las Casas edited out, will never be known. Secondly, even if we accept that the record that has come down to us was a faithful account of what Columbus actually wrote, he clearly came to the Caribbean with preconceived notions about the nature ofprimitive peoples and the idea of the noble savage : As soon as day broke, there came to the

34 FIELD ARCHAEOLOGY

shore many of these men, all youths and all of a good height, very handsome people (Columbus 1960). Much of the detail recorded is perhaps more useful to archaeologists: That day there came many boats or canoes to the ship, to barter articles of spun cotton and the nets in which they sleep, which are hammocks (Columbus 1960). Canoes, cotton and hammocks rarely survive in the archaeological record in the warm, humid tropics.

When dealing with historic periods the documentary archive is, of course, vast but biased. A peasant farmstead in the countryside may never have been written about, while royal castles may have documents detailing the precise number of nails bought to re-roof a kitchen. In Britain the Public Record Office (PRO) and county-based Record Offices (CRO) are the main source of documentary evidence.

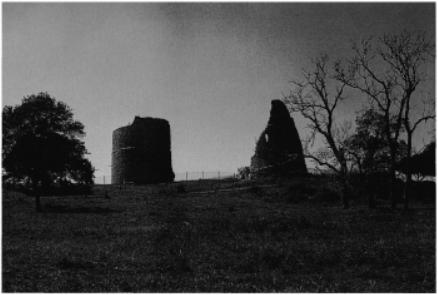

Property in Britain owned by the Church and State have some of the most detailed records. The problem with all this detailed data is often relating it to the actual archaeology on the ground. The royal castle constructed at Hadleigh in Essex is a good example of this problem (Drewett 1975). The castle started its life as a private castle, built by Hubert de Burgh, Earl of Kent and Justiciar of England. He was granted a licence by King Henry III in 1230 (Patent Rolls, 1225 32, in H. M. Colvin (ed.), The history of the king s works). We know from elsewhere, however, that these royal licences were sometimes granted to regularize a situation. Was the castle, therefore, actually built in or after 1230, or was the licence granted for a castle already in existence? Looking at the surviving remains of the castle, its earliest phase of construction a small bailey with square angle towers can be determined.Are these remains actually those of the 1230 castle mentioned in the document, or was that castle either elsewhere near by or destroyed to make way for the construction of what we now see as the first phase?

Records of Hadleigh castle show endless small sums of money spent onrepairs and rebuilding: 25 shillings in 1240, £25 in 1270 71, construction of a new gate in the postern in 1312 13 and repairinga breachinthewall in1320 21.Noneof thisdetailcouldbe detectedinthe archaeological record (Drewett 1975). It is not until King Edward III spent £2,287 on the construction of a totally new barbican gatehouse on the northern side of the castle and two great angle towers at the eastern end of the castle that the documentary references show clearly in the archaeological record (Fig. 3.1).

The range of documents available to archaeologists in their quest for archaeological sites is enormous, and generally increases through time.Archaeologists working in medieval and postmedieval archaeology in Britain have numerous potential sources. Court rolls of manors often offer details of land use, enclosures, fields and settlements. Manorial surveys may list tenants and numbers of buildings on the manor, as well as details of stock numbers. For the latemedieval and post-medieval period, probate inventories may list details of a yeoman farmer s total property, from buildings to cooking pots. Title deeds, wills and lawsuits often provide information about site locations. For post-medieval archaeology in Britain, tithe and enclosure awards are a valuable source of information.

The main problems with using written sources to locate archaeological sites are firstly the reliability of the document itself, and secondly whether there is enough information to locate an actual site in the landscape. This is a separate problem from that of using such documents to write history, where precise location within a parish, for example, may or may not be important.

FINDING ARCHAEOLOGICAL SITES |

35 |

Figure 3.1 Documentary evidence clearly indicated that these two towers, together with a new gatehouse, were constructed at Hadleigh Castle, Essex, by Edward III at a cost of £2,287.

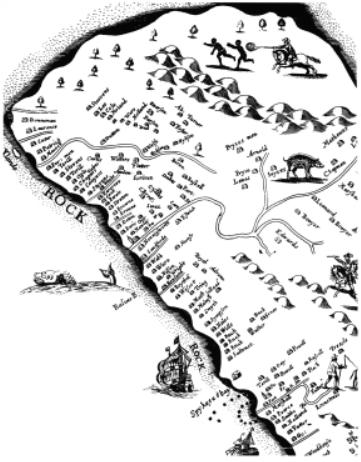

Maps are perhaps one of the most important types of document to aid in the location of sites. The earliest surviving maps date back to about 2300 BC when the Babylonians created maps on clay tablets. Until the eighteenth century, however, maps tended to be pictorial rather than strictly accurate in detail. Earlier maps may locate countries, towns, villages and major natural features reasonably accurately, but individual structures may only be represented pictorially in their approximate position at no particular scale. Richard Ligon s 1657 map of Barbados (Ligon 1657) is a good example of this type of map. The island is very roughly the right shape, but houses are shown more or less regularly spaced around the coast, in the right order by land owner (Fig. 3.2). To locate one of these structures on the ground from this map is virtually impossible.

In Britain good maps date back to the sixteenth century, with the great cartographers like Saxton, Speed and Norden all working in the latter part of the century. For great accuracy, however, one has to wait for the publication of the first Ordnance Survey maps in 1795. These maps, of course, not only provide data about the late eighteenth century but also all notable features surviving in the landscape from earlier periods. They thus become not only a source for archaeologists trying to locate sites of historic periods, but also potentially prehistoric sites like round barrows that survived until the eighteenth century but have been destroyed since. However, it was many years before all of Britain was mapped accurately, and even then rural areas were mapped at a smaller scale than urban areas.

36 FIELD ARCHAEOLOGY

Figure 3.2 Extract from Richard Ligon s 1657 map of Barbados, illustrating the problem of locating buildings from historic maps.

In addition to written documents and maps, pictures may provide a good source of information about the location of sites, but only if the picture has within it something that can be clearly located in the landscape today. Thus early pictures like those that appear, for example, in the Aztecs Veitia Codex provide great detail about how people did what, but not always exactly where, which is of course essential for locating sites. Again one generally has to wait until the eighteenth century, when the great illustrators like Samuel Buck produced architectural drawings with enough accurate detail to locate sites. Nineteenth-century photographs of now-demolished historic buildings, or even prehistoric sites, may also be a useful source of locational information.

Place names provide another source of information about the possible location of archaeological sites. Place-name studies are, however, not straightforward and not many