- •Preface and Acknowledgments

- •Contents

- •Contributors

- •1: Embryology for Urologists

- •Introduction

- •Renal Development

- •Pronephros

- •Mesonephros

- •Metanephros

- •Development of the Collecting System

- •Critical Steps in Further Development

- •Anomalies of the Kidney

- •Renal Agenesis

- •Renal Aplasia

- •Renal Hypoplasia

- •Renal Ectopia

- •Renal Fusion

- •Ureteral Development

- •Anomalies of Origin

- •Anomalies of Number

- •Incomplete Ureteral Duplication

- •Complete Ureteral Duplication

- •Ureteral Ectopia

- •Embryology of Ectopia

- •Clinical Correlation

- •Location of Ectopic Ureteral Orifices – Male (in Descending Order According to Incidence)

- •Symptoms

- •Ureteroceles

- •Congenital Ureteral Obstruction

- •Pipestem Ureter

- •Megaureter-Megacystis Syndrome

- •Prune Belly Syndrome

- •Vascular Ureteral Obstructions

- •Division of the Urogenital Sinus

- •Bladder Development

- •Urachal Anomalies

- •Cloacal Duct Anomalies

- •Other Bladder Anomalies

- •Bladder Diverticula

- •Bladder Extrophy

- •Gonadal Development

- •Testicular Differentiation

- •Ovarian Differentiation

- •Gonadal Anomalies

- •Genital Duct System

- •Disorders of Testicular Function

- •Female Ductal Development

- •Prostatic Urethral Valves

- •Gonadal Duct Anomalies

- •External Genital Development

- •Male External Genital Development

- •Female External Genital Development

- •Anomalies of the External Genitalia

- •References

- •2: Gross and Laparoscopic Anatomy of the Upper Urinary Tract and Retroperitoneum

- •Overview

- •The Kidneys

- •The Renal Vasculature

- •The Renal Collecting System

- •The Ureters

- •Retroperitoneal Lymphatics

- •Retroperitoneal Nerves

- •The Adrenal Glands

- •References

- •3: Gross and Laparoscopic Anatomy of the Lower Urinary Tract and Pelvis

- •Introduction

- •Female Pelvis

- •Male Pelvis

- •Pelvic Floor

- •Urinary Bladder

- •Urethra

- •Male Urethra

- •Female Urethra

- •Sphincter Mechanisms

- •The Bladder Neck Component

- •The Urethral Wall Component

- •The External Urethral Sphincter

- •Summary

- •References

- •4: Anatomy of the Male Reproductive System

- •Testis and Scrotum

- •Spermatogenesis

- •Hormonal Regulation of Spermatogenesis

- •Genetic Regulation of Spermatogenesis

- •Epididymis and Ductus Deferens

- •Accessory Sex Glands

- •Prostate

- •Seminal Vesicles

- •Bulbourethral Glands

- •Penis

- •Erection and Ejaculation

- •References

- •5: Imaging of the Upper Tracts

- •Anatomy of the Upper Tracts and Introduction to Imaging Modalities

- •Introduction

- •Renal Upper Tract Basic Anatomy

- •Modalities Used for Imaging the Upper Tracts

- •Ultrasound

- •Radiation Issues

- •Contrast Issues

- •Renal and Upper Tract Tumors

- •Benign Renal Tumors

- •Transitional Cell Carcinoma

- •Renal Mass Biopsy

- •Renal Stone Disease

- •Ultrasound

- •Plain Radiographs and IVU

- •Renal Cystic Disease

- •Benign Renal Cysts

- •Hereditary Renal Cystic Disease

- •Complex Renal Cysts

- •Renal Trauma

- •References

- •Introduction

- •Pathophysiology

- •Susceptibility and Resistance

- •Epidemiological Breakpoints

- •Clinical Breakpoints

- •Pharmacodynamic Parameters

- •Pharmacokinetic Parameters

- •Fosfomycin

- •Nitrofurantoin

- •Pivmecillinam

- •b-Lactam-Antibiotics

- •Penicillins

- •Cephalosporins

- •Carbapenems

- •Aminoglycosides

- •Fluoroquinolones

- •Trimethoprim, Cotrimoxazole

- •Glycopeptides

- •Linezolid

- •Conclusion

- •References

- •7: An Overview of Renal Physiology

- •Introduction

- •Body Fluid Compartments

- •Regulation of Potassium Balance

- •Regulation of Acid–Base Balance

- •Diuretics

- •Suggested Reading

- •8: Ureteral Physiology and Pharmacology

- •Ureteral Anatomy

- •Modulation of Peristalsis

- •Ureteral Pharmacology

- •Conclusion

- •References

- •Introduction

- •Afferent Signaling Pathways

- •Efferent Signaling

- •Parasympathetic Nerves

- •Sympathetic Nerves

- •Vesico-Spinal-Vesical Micturition Reflex

- •Peripheral Targets

- •Afferent Signaling Mechanisms

- •Urothelium

- •Myocytes

- •Cholinergic Receptors

- •Muscarinic Receptors

- •Nicotinic Receptors

- •Adrenergic Receptors (ARs)

- •a-Adrenoceptors

- •b-Adrenoceptors

- •Transient Receptor Potential (TRP) Receptors

- •Phosphodiesterases (PDEs)

- •CNS Targets

- •Opioid Receptors

- •Serotonin (5-HT) Mechanisms

- •g-Amino Butyric Acid (GABA) Mechanisms

- •Gabapentin

- •Neurokinin and Neurokinin Receptors

- •Summary

- •References

- •10: Pharmacology of Sexual Function

- •Introduction

- •Sexual Desire/Arousal

- •Endocrinology

- •Steroids in the Male

- •Steroids in the Female

- •Neurohormones

- •Neurotransmitters

- •Dopamine

- •Serotonin

- •Pharmacological Strategies

- •CNS Drugs

- •Enzyme-inducing Antiepileptic Drugs

- •Erectile Function

- •Ejaculatory Function

- •Premature Ejaculation

- •Abnormal Ejaculation

- •Conclusions

- •References

- •Epidemiology

- •Calcium-Based Urolithiasis

- •Uric Acid Urolithiasis

- •Infectious Urolithiasis

- •Cystine-Based Urolithiasis

- •Aims

- •Who Deserves Metabolic Evaluation?

- •Metabolic Workup for Stone Producers

- •Medical History and Physical Examination

- •Stone Analysis

- •Serum Chemistry

- •Urine Evaluation

- •Urine Cultures

- •Urinalysis

- •Twenty-Four Hour Urine Collections

- •Radiologic Imaging

- •Medical Management

- •Conservative Management

- •Increased Fluid Intake

- •Citrus Juices

- •Dietary Restrictions

- •Restricted Oxalate Diet

- •Conservative Measures

- •Selective Medical Therapy

- •Absorptive Hypercalciuria

- •Thiazide

- •Orthophosphate

- •Renal Hypercalciuria

- •Primary Hyperparathyroidism

- •Hyperuricosuric Calcium Oxalate Nephrolithiasis

- •Enteric Hyperoxaluria

- •Hypocitraturic Calcium Oxalate Nephrolithiasis

- •Distal Renal Tubular Acidosis

- •Chronic Diarrheal States

- •Thiazide-Induced Hypocitraturia

- •Idiopathic Hypocitraturic Calcium Oxalate Nephrolithiasis

- •Hypomagnesiuric Calcium Nephrolithiasis

- •Gouty Diathesis

- •Cystinuria

- •Infection Lithiasis

- •Summary

- •References

- •12: Molecular Biology for Urologists

- •Introduction

- •Inherited Changes in Cancer Cells

- •VEGR and Cell Signaling

- •Targeting mTOR

- •Conclusion

- •References

- •13: Chemotherapeutic Agents for Urologic Oncology

- •Introduction

- •Bladder Cancer

- •Muscle Invasive Bladder Cancer

- •Metastatic Bladder Cancer

- •Conclusion

- •Prostate Cancer

- •Other Chemotherapeutic Drugs or Combinations for Treating HRPC

- •Conclusion

- •Renal Cell Carcinoma

- •Chemotherapy

- •Immunotherapy

- •Angiogenesis Inhibitor Drugs

- •Conclusion

- •Testicular Cancer

- •Stage I Seminoma

- •Stage I non-seminomatous Germ Cell Tumours (NSGCT)

- •Metastatic Germ Cell Tumours

- •Low-Volume Metastatic Disease (Stage II A/B)

- •Advanced Metastatic Disease

- •Salvage Chemotherapy for Relapsed or Refractory Disease

- •Conclusion

- •Penile Cancer

- •Side Effects of Chemotherapy

- •Conclusion

- •References

- •14: Tumor and Transplant Immunology

- •Antibodies

- •Cytotoxic and T-helper Cells

- •Immunosuppression

- •Induction Therapy

- •Maintenance Therapy

- •Rejection

- •Posttransplant Lymphoproliferative Disease

- •Summary

- •References

- •15: Pathophysiology of Renal Obstruction

- •Causes of Renal Obstruction

- •Effects on Prenatal Development

- •Prenatal Hydronephrosis

- •Spectrum of Renal Abnormalities

- •Renal Functional Changes

- •Renal Growth/Counterbalance

- •Vascular Changes

- •Inflammatory Mediators

- •Glomerular Development Changes

- •Mechanical Stretch of Renal Tubules

- •Unilateral Versus Bilateral

- •Limitations of Animal Models

- •Future Research

- •Issues in Patient Management

- •Diagnostic Imaging

- •Ultrasound

- •Intravenous Urography

- •Antegrade Urography and the Whitaker Test

- •Nuclear Renography

- •Computed Tomography

- •Magnetic Resonance Urography

- •Hypertension

- •Postobstructive Diuresis

- •References

- •Introduction

- •The Normal Lower Urinary Tract

- •Anatomy

- •Storage Function

- •Voiding Function

- •Neural Control

- •Symptoms

- •Flow Rate and Post-void Residual

- •Voiding Cystometry

- •Male

- •Female

- •Neurourology

- •Conclusions

- •References

- •17: Urologic Endocrinology

- •The Testis

- •Normal Androgen Metabolism

- •Epidemiological Aspects

- •Prostate

- •Brain

- •Muscle Mass and Adipose Tissue

- •Bones

- •Ematopoiesis

- •Metabolism

- •Cardiovascular System

- •Clinical Assessment

- •Biochemical Assessment

- •Treatment Modalities

- •Oral Preparations

- •Parenteral Preparations

- •Transdermal Preparations

- •Side Effects and Treatment Monitoring

- •Body Composition

- •Cognitive Decline

- •Bone Metabolism

- •The Kidneys

- •Endocrine Functions of the Kidney

- •Erythropoietin

- •Calcitriol

- •Renin

- •Paraneoplastic Syndromes

- •Hypercalcemia

- •Hypertension

- •Polycythemia

- •Other Endocrine Abnormalities

- •References

- •General Physiology

- •Prostate Innervation

- •Summary

- •References

- •Wound Healing

- •Inflammation

- •Proliferation

- •Remodeling

- •Principles of Plastic Surgery

- •Tissue Characteristics

- •Grafts

- •Flap

- •References

- •Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms

- •Storage Phase

- •Voiding Phase

- •Return to Storage Phase

- •Urodynamic Parameters

- •Urodynamic Techniques

- •Volume Voided Charts

- •Pad Testing

- •Typical Test Schedule

- •Uroflowmetry

- •Post Voiding Residual

- •Further Diagnostic Evaluation of Patients

- •Cystometry with or Without Video

- •Cystometry

- •Videocystometrography (Cystometry + Cystourethrography)

- •Cystometric Findings

- •Comment:

- •Measurements During the Storage Phase:

- •Measurements During the Voiding Phase:

- •Abnormal Function

- •Disorders of Sensation

- •Causes of Hypersensitive Bladder Sensation

- •Causes of Hyposensitive Bladder Sensation

- •Disorders of Detrusor Motor Function

- •Bladder Outflow Tract Dysfunction

- •Detrusor–Urethral Dyssynergia

- •Detrusor–Bladder Neck Dyssynergia

- •Detrusor–Sphincter Dyssynergia

- •Complex Urodynamic Investigation

- •Urethral Pressure Measurement

- •Technique

- •Neurophysiological Evaluation

- •Conclusion

- •References

- •Endoscopy

- •Cystourethroscopy

- •Ureteroscopy and Ureteropyeloscopy

- •Nephroscopy

- •Virtual Reality Simulators

- •Lasers

- •Clinical Application of Lasers

- •Condylomata Acuminata

- •Urolithiasis

- •Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia

- •Ureteral and Urethral Strictures

- •Conclusion

- •References

- •Introduction

- •The Prostatitis Syndromes

- •The Scope of the Problem

- •Category III CP/CPPS

- •The Goal of Treatment

- •Conservative Management

- •Drug Therapy

- •Antibiotics

- •Anti-inflammatories

- •Alpha blockers

- •Hormone Therapies

- •Phytotherapies

- •Analgesics, muscle relaxants and neuromodulators

- •Surgery

- •A Practical Management Plan

- •References

- •Orchitis

- •Definition and Etiology

- •Clinical Signs and Symptoms

- •Diagnostic Evaluation

- •Treatment of Infectious Orchitis

- •Epididymitis

- •Definition and Etiology

- •Clinical Signs and Symptoms

- •Diagnostic Evaluation of Epididymitis

- •Treatment of Acute Epididymitis

- •Treatment of Chronic Epididymitis

- •Treatment of Spermatic Cord Torsion

- •Fournier’s Gangrene

- •Definition and Etiology

- •Risk Factors

- •Clinical Signs and Symptoms

- •Diagnostic Evaluation

- •Treatment

- •References

- •Fungal Infections

- •Candidiasis

- •Aspergillosis

- •Cryptococcosis

- •Blastomycosis

- •Coccidioidomycosis

- •Histoplasmosis

- •Radiographic Findings

- •Treatment

- •Tuberculosis

- •Clinical Manifestations

- •Diagnosis

- •Treatment

- •Schistosomiasis

- •Clinical Manifestations

- •Diagnosis

- •Treatment

- •Filariasis

- •Clinical Manifestations

- •Diagnosis

- •Treatment

- •Onchocerciasis

- •References

- •25: Sexually Transmitted Infections

- •Introduction

- •STIs Associated with Genital Ulcers

- •Herpes Simplex Virus

- •Diagnosis

- •Treatment

- •Chancroid

- •Diagnosis

- •Treatment

- •Syphilis

- •Diagnosis

- •Treatment

- •Lymphogranuloma Venereum

- •Diagnosis

- •Treatment

- •Chlamydia

- •Diagnosis

- •Treatment

- •Gonorrhea

- •Diagnosis

- •Treatment

- •Trichomoniasis

- •Diagnosis

- •Treatment

- •Human Papilloma Virus

- •Diagnosis

- •Treatment

- •Scabies

- •Diagnosis

- •Treatment

- •References

- •26: Hematuria: Evaluation and Management

- •Introduction

- •Classification of Hematuria

- •Macroscopic Hematuria

- •Microscopic Hematuria

- •Dipstick Hematuria

- •Pseudohematuria

- •Factitious Hematuria

- •Menstruation

- •Aetiology

- •Malignancy

- •Urinary Calculi

- •Infection and Inflammation

- •Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia

- •Trauma

- •Drugs

- •Nephrological Causes

- •Assessment

- •History

- •Examination

- •Investigations

- •Dipstick Urinalysis

- •Cytology

- •Molecular Tests

- •Blood Tests

- •Flexible Cystoscopy

- •Upper Urinary Tract Evaluation

- •Renal USS

- •KUB Abdominal X-Ray

- •Intravenous Urography (IVU)

- •Computed Tomography (CT)

- •Retrograde Urogram Studies

- •Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI)

- •Additional Tests and Renal Biopsy

- •Intractable Hematuria

- •Loin Pain Hematuria Syndrome

- •References

- •27: Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia (BPH)

- •Historical Background

- •Pathophysiology

- •Patient Assessment

- •Treatment of BPH

- •Watchful Waiting

- •Drug Therapy

- •Interventional Therapies

- •Conclusions

- •References

- •28: Practical Guidelines for the Treatment of Erectile Dysfunction and Peyronie´s Disease

- •Erectile Dysfunction

- •Introduction

- •Diagnosis

- •Basic Evaluation

- •Cardiovascular System and Sexual Activity

- •Optional Tests

- •Treatment

- •Medical Treatment

- •Oral Agents

- •Phosphodiesterase Type 5 (PDE 5) Inhibitors

- •Nonresponders to PDE5 Inhibitors

- •Apomorphine SL

- •Yohimbine

- •Intracavernosal and Intraurethral Therapy

- •Intracavernosal Injection (ICI) Therapy

- •Intraurethral Therapy

- •Vacuum Constriction Devices

- •Surgical Therapy

- •Conclusion

- •Peyronie´s Disease (PD)

- •Introduction

- •Oral Drug Therapy

- •Intralesional Drug Therapy

- •Iontophoresis

- •Radiation Therapy

- •Surgical Therapy

- •References

- •29: Premature Ejaculation

- •Introduction

- •Epidemiology

- •Defining Premature Ejaculation

- •Voluntary Control

- •Sexual Satisfaction

- •Distress

- •Psychosexual Counseling

- •Pharmacological Treatment

- •On-Demand Treatment with Tramadol

- •Topical Anesthetics

- •Phosphodiesterase Inhibitors

- •Surgery

- •Conclusion

- •References

- •30: The Role of Interventional Management for Urinary Tract Calculi

- •Contraindications to ESWL

- •Complications of ESWL

- •PCNL Access

- •Instrumentation for PCNL

- •Nephrostomy Drains Post PCNL

- •Contraindications to PCNL

- •Complications of PCNL

- •Semirigid Ureteroscopy

- •Flexible Ureteroscopy

- •Electrohydraulic Lithotripsy (EHL)

- •Ultrasound

- •Ballistic Lithotripsy

- •Laser Lithotripsy

- •Ureteric Stents

- •Staghorn Calculi

- •Lower Pole Stones

- •Horseshoe Kidneys and Stones

- •Calyceal Diverticula Stones

- •Stones and PUJ Obstruction

- •Treatment of Ureteric Colic

- •Medical Expulsive Therapy (MET)

- •Intervention for Ureteric Stones

- •Stones in Pregnancy

- •Morbid Obesity

- •References

- •Anatomy and Function

- •Pathophysiology

- •Management

- •Optical Urethrotomy/Dilatation

- •Urethral Stents

- •Preoperative Assessment

- •Urethroplasty

- •Anastomotic Urethroplasty

- •Substitution Urethroplasty

- •Grafts Versus Flaps

- •Oral Mucosal Grafts

- •Tissue Engineering

- •Graft Position

- •Conclusion

- •References

- •32: Urinary Incontinence

- •Epidemiology and Risk Factors

- •Pathophysiology

- •Urge Incontinence

- •Conservative Treatments

- •Pharmacotherapy

- •Invasive/ Surgical Therapies

- •Stress Urinary Incontinence

- •Male SUI Therapies

- •Female SUI Therapies

- •Mixed Urinary Incontinence

- •Conclusions

- •References

- •33: Neurogenic Bladder

- •Introduction

- •Examination and Diagnostic Tests

- •History and Physical Examination

- •Imaging

- •Urodynamics (UDS)

- •Evoked Potentials

- •Classifications

- •Somatic Pathways

- •Brain Lesions

- •Cerebrovascular Accident (CVA)

- •Parkinson’s Disease (PD)

- •Multiple Sclerosis

- •Huntington’s Disease

- •Dementias

- •Normal Pressure Hydrocephalus (NPH)

- •Tumors

- •Psychiatric Disorders

- •Spinal Lesions and Pathology

- •Intervertebral Disk Prolapse

- •Spinal Cord Injury (SCI)

- •Transverse Myelitis

- •Peripheral Neuropathies

- •Metabolic Neuropathies

- •Pelvic Surgery

- •Treatment

- •Summary

- •References

- •34: Pelvic Prolapse

- •Introduction

- •Epidemiology

- •Anatomy and Pathophysiology

- •Evaluation and Diagnosis

- •Outcome Measures

- •Imaging

- •Urodynamics

- •Indications for Management

- •Biosynthetics

- •Surgical Management

- •Anterior Compartment Repair

- •Uterine/Apical Prolapse

- •Enterocele Repair

- •Conclusion

- •References

- •35: Urinary Tract Fistula

- •Introduction

- •Urogynecologic Fistula

- •Vesicovaginal Fistula

- •Etiology and Risk Factors

- •Clinical Factors

- •Evaluation and Diagnosis

- •Pelvic Examination

- •Cystoscopy

- •Imaging

- •Treatment

- •Conservative Management

- •Surgical Management

- •Urethrovaginal Fistula

- •Etiology and Presentation

- •Diagnosis and Management

- •Ureterovaginal Fistula

- •Etiology and Presentation

- •Diagnosis and Management

- •Vesicouterine Fistula

- •Etiology and Presentation

- •Diagnosis and Management

- •Uro-Enteric Fistula

- •Vesicoenteric Fistula

- •Pyeloenteric Fistula

- •Urethrorectal Fistula

- •References

- •36: Urologic Trauma

- •Introduction

- •Kidney

- •Expectant Management

- •Endovascular Therapy

- •Operative Intervention

- •Operative Management: Follow-up

- •Reno-Vascular Injuries

- •Pediatric Renal Injuries

- •Adrenal

- •Ureter

- •Diagnosis

- •Treatment

- •Delayed Diagnosis

- •Bladder and Posterior Urethra

- •Bladder Injuries: Initial Management

- •Bladder Injuries: Formal Repair

- •Anterior Urethral Trauma

- •Fractured Penis

- •Penile Amputation

- •Scrotal and Testicular Trauma

- •Imaging

- •CT-IVP (CT with Delayed Images)

- •Technique

- •Cystogram

- •Technique

- •Retrograde Urethrogram (RUG)

- •Technique

- •Retrograde Pyelogram (RPG)

- •Technique

- •One-Shot IVP

- •Technique

- •References

- •37: Bladder Cancer

- •Who Should Be Investigated?

- •Epidemiology

- •Risk Factors

- •Role of Screening

- •Signs and Symptoms

- •Imaging

- •Cystoscopy

- •Urine Tests

- •PDD-Assisted TUR

- •Pathology

- •NMIBC and Risk Groups

- •Intravesical Chemotherapy

- •Intravesical Immunotherapy

- •Immediate Cystectomy and CIS

- •Radical Cystectomy with Pelvic Lymph Node Dissection

- •sexual function-preserving techniques

- •Bladder-Preservation Treatments

- •Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy

- •Adjuvant Chemotherapy

- •Preoperative Radiotherapy

- •Follow-up After TUR in NMIBC

- •References

- •38: Prostate Cancer

- •Introduction

- •Epidemiology

- •Race

- •Geographic Variation

- •Risk Factors and Prevention

- •Family History

- •Diet and Lifestyle

- •Prevention

- •Screening and Diagnosis

- •Current Screening Recommendations

- •Biopsy

- •Pathology

- •Prognosis

- •Treatment of Prostate Cancer

- •Treatment for Localized Prostate Cancer (T1, T2)

- •Radical Prostatectomy

- •EBRT

- •IMRT

- •Brachytherapy

- •Treatment for Locally Advanced Prostate Cancer (T3, T4)

- •EBRT with ADT

- •Radical Prostatectomy

- •Androgen-Deprivation Therapy

- •Summary

- •References

- •39: The Management of Testis Cancer

- •Presentation and Diagnosis

- •Serum Tumor Markers

- •Primary Surgery

- •Testis Preserving Surgery

- •Risk Stratification

- •Surveillance Versus Primary RPLND

- •Primary RPLND

- •Adjuvant Treatment for High Risk

- •Clinical Stage 1 Seminoma

- •Risk-Stratified Adjuvant Treatment

- •Adjuvant Radiotherapy

- •Adjuvant Low Dose Chemotherapy

- •Primary Combination Chemotherapy

- •Late Toxicity

- •Salvage Strategies

- •Conclusion

- •References

- •Index

3

Gross and Laparoscopic Anatomy of the Lower Urinary Tract and Pelvis

Bastian Amend and Arnulf Stenzl

Introduction

An overview of the gross and laparoscopic anatomy of the lower urinary tract should summarize both long-standing anatomic knowledge and current scientific findings. In few fields has the anatomic understanding grown as much as in urology, especially concerning the anatomy of the lower urinary tract. Whereas the gross anatomy is already well known, now research is increasingly contributing to our understanding of the microscopic level. This concerns especially the detailed anatomy and topography of the sphincter mechanism of the urinary bladder, the routing and function of the neural structures in the pelvis and,for example,the anatomic structure of the pelvic floor. The transmission of these new findings in combination with traditional anatomic knowledge into urological practice, including the growing field of laparoscopic surgery, is essential to maintain and improve the success of treatments for our patients. The following chapter gives a clear, detailed and informative summary of the anatomy of the lower urinary tract,especially considering the requirements of laparoscopic and endoscopic surgery.

The History of the Study of the

Urological Anatomy

The historiography of urology goes back to 1000 BC in Egypt. The first description of a bladder

catheter made of bronze dates to this time, and bladder stone surgery also seems to have been practiced. The prostate was first described by Herophilus of Chalcedon in 300 BC. Human cadaver sections enabled this first glimpse.

After the widespread rejection of anatomical studies up to the Middle Ages, detailed descriptions of human anatomy began to emerge again with the work of Leonardo da Vinci (1452–1519), Andreas Vesalius (1514–1564) from Brussels and their successor Eustachi (1500–1574). The anatomy of the urogenital tract was mainly revealed by Étienne de la Rivière of Paris with the description of the seminal vesicles,Marcellus Malpighi (1628–1694) with the exploration of renal functioning and Lorenzo Bellini (1643– 1704) with the identification of the renal tubuli. The progress of microscopic examinations further advanced the basic anatomical knowledge. In 1684, Mery described the existence of the bulbourethral glands, which was later attributed to Cowper.

The founder of the study of the pathology of the urogenital tract was Giovanni Battista Morgagni (1682–1771) with his work “De sedibus et causis morborum”. Giovanni Battista Morgagni is considered the first to describe prostatic hyperplasia.

One of the milestones in urology – urological endoscopy – goes back to Phillip Bozzini of Frankfurt who invented the first endoscope using candlelight in 1806. This made possible the exploration of the internal anatomical details of a living individual.1

C.R. Chapple and W.D. Steers (eds.), Practical Urology: Essential Principles and Practice, |

43 |

DOI: 10.1007/978-1-84882-034-0_3, © Springer-Verlag London Limited 2011 |

|

|

|

44 |

|

|

|

|

|

Practical Urology: EssEntial PrinciPlEs and PracticE |

Topographic Anatomy of the |

could accompany the components of the sper- |

|

|

|

|

Anterior Abdominal Wall |

matic cord through the inguinal canal. The |

|

external iliac vessels and the iliopsoas muscle |

||

|

|

leave the pelvis below the inguinal ligament, |

The increasing significance of laparoscopic pro- |

which connects the anterior superior iliac spine |

|

cedures, especially for intrapelvic and prostate |

to the pubic tubercle. The lacunar ligament is |

|

surgery, necessitates a detailed understanding |

located directly medial to the external iliac vein |

|

of the topographic anatomy of the anterior |

connecting the inguinal ligament to the supe- |

|

abdominal wall. Figure 3.1 illustrates the differ- |

rior pubic ramus and represents the caudal |

|

ent structures in addition to a laparoscopic view |

extent during lymphadenectomy for prostate or |

|

of the male pelvis (Fig. 3.2) at the beginning of |

bladder cancer.2 |

|

robotic-assisted radical prostatectomy. |

|

|

Five tissue folds subdivide the anterior |

Female Pelvis |

|

abdominal wall. The former embryonic urachus |

|

|

forms the median umbilical ligament between |

A plain promontorium and wide-open iliac |

|

the urinary bladder and the umbilicus. On both |

wings characterize the female pelvic bone. The |

|

sides lateral to the median umbilical ligament, |

peritoneal pelvic cavity harbors the urinary |

|

the remnants of the fetal umbilical arteries |

bladder, the ureters, the uterus, the vagina, the |

|

shape the medial umbilical ligaments/folds – the |

ovaries, the oviducts and the rectum. The uterus, |

|

space in between is called the supravesical fossa. |

in between the urinary bladder and the rectum, |

|

During cystectomy, the medial umbilical liga- |

leads to varying peritoneal conditions, starting |

|

ments are the main structures to identify and |

from the anterior abdominal wall. The parietal |

|

control the superior vesical pedicle including |

peritoneum covers approximately the upper half |

|

the superior vesical artery. The inferior epigas- |

of the urinary bladder, the uterus, the adnexa |

|

tric vessels underlie the lateral umbilical liga- |

and the anterior wall of the rectum. Thereby the |

|

ments/folds. These structures have important |

parietal peritoneum forms two parts of the |

|

significance regarding hernia classification. |

abdominal cavity: the rectouterine excavation |

|

Medial to the lateral umbilical fold, the medial |

(Douglas’ fold) and the vesicouterine excava- |

|

inguinal fossa represents the passage of direct |

tion. The peritoneal fold between the uterus/ |

|

inguinal hernias. The lateral inguinal fossa cor- |

cervix and the pelvic wall is called the ligamen- |

|

responds to the deep inguinal ring – the entry to |

tum latum or broad ligament, although these |

|

the inguinal canal. An indirect inguinal hernia |

structures lack some of the typical features of a |

|

Figure 3.1. topographic anatomy of the male pelvis. Left: laparoscopic view at the beginning of robotic-assisted laparoscopic prostatectomy. Right: drawing of the anatomical structures of the inguinal region in addition to the left intraoperative view.

45

gross and laParoscoPic anatomy of thE lowEr Urinary tract and PElvis

Anterior abdominal wall

Cavum Retzii and

urinary bladder

CO2

Pubic bone

Bowel

Figure 3.2. the drawing illustrates the laparoscopic line of sight during pelvic or prostate surgery.

ligament in the anatomical sense. The uterine artery, the uterine venous plexus and parts of the distal third of the ureters are included in the broad ligament. Ovaries and the Fallopian tubes are also joined to the broad ligament by a peritoneal duplication. The ovaries receive their blood supply through the suspensory ligament, and they are connected to the uterus by the ovarian ligament. At least, the round ligaments represent connections between the deep inguinal rings and the uterine horns.

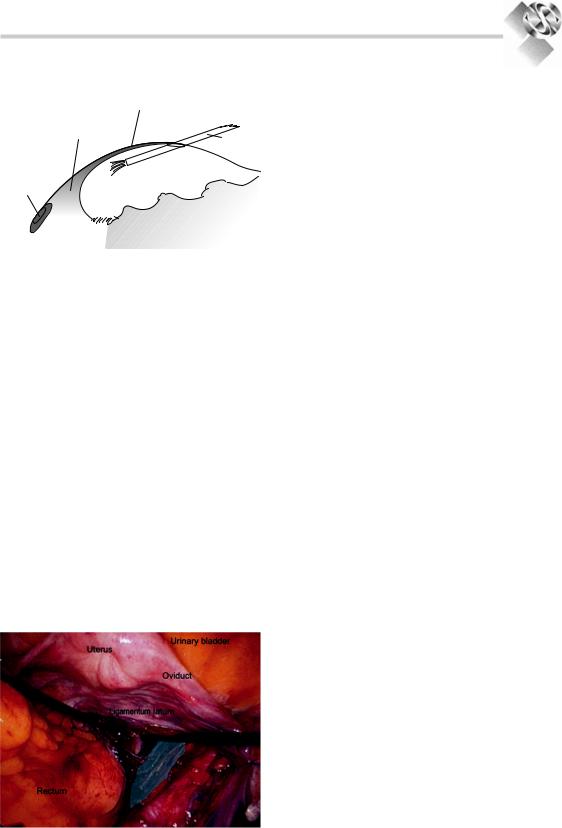

The rectouterine folds mark the borders of the rectouterine pouch – they consist of fibrous tissue and smooth muscle fibers, and also include the inferior hypogastric plexus (Fig. 3.3).

The pelvic fascia with its parietal and visceral layer covers the borders of the subperitoneal space; the clinical synonym is “endopelvic fascia”. The endopelvic fascia also forms the

Figure 3.3. laparoscopic view in the female pelvis. the right rectovaginal fold is marked in lucent blue.

superior layer of the fascia of the pelvic and urogenital diaphragm. The urinary bladder is attached to the pubic bone/symphysis pubis via the pubovesical ligaments (analogous to the puboprostatic ligaments in male humans, see also below) with lateral connections to the superior layer of the fascia of the pelvic diaphragm. Between the different subperitoneal organs, connective and fatty tissue fills the resulting spaces (presacral, prevesical paracervical, parametrial). The stability of the uterus and the cervix is guaranteed by the rectouterine (synonym, sacrouterine) ligament and the topography of the other pelvic organs. The cardinal ligaments (synonym, transverse cervical ligaments) on the base of the broad ligament, joining the cervix and the lateral pelvic wall, are not there at birth, but are shaped throughout a lifetime by the increasingly compact and strong connective tissue. They increasingly support the topographical position of the cervix.2-4

Male Pelvis

In contrast to the female pelvis, in male humans the pelvic bone is narrower and marked by a more protruding promontorium, resulting in a heart-shaped pelvic entry. The pelvis accommodates the urinary bladder, the ureters, the prostate, the seminal vesicles, the deferent ducts and the rectum. The parietal peritoneum also covers the pelvic organs starting from the anterior abdominal wall to the anterior rectal wall. Between the urinary bladder and the rectum, the deepest point of the abdominal cavity forms the rectovesical excavation. On both sides the rectovesical fold confines the excavation and includes the inferior hypogastric plexus. The deferent ducts shape the paravesical fossa by raising a peritoneal fold.

The subperitoneal space in front of and lateral to the urinary bladder is clinically called the cavum retzii. A look at the existing literature concerning the anatomical conditions of the subperitoneal fascias, especially the prostate-sur- rounding tissue and the formation of the so-called Denonvilliers’ fascia, demonstrates an inconsistent presentation and nomenclature. The following explanations will outline the most usually published anatomical findings and interpretations. The pelvic fascia in males also consists of two parts: a parietal layer,which covers the lateral