Lecture 6 Proto-Germanic Languages

Introduction

PGL (often abbreviated PGmc.), or Common Germanic, as it is sometimes known, is the unattested, reconstructed common ancestor (proto-language) of all the Germanic languages such as modern English, Frisian, Dutch, Afrikaans, German, Luxembourgish, Danish, Norwegian, Icelandic, Faroese, and Swedish

The Proto-Germanic language is not directly attested by any surviving texts but has been reconstructed using the comparative method. However, a few surviving inscriptions in a runic script from Scandinavia dated to c. 200 are thought to represent a stage of Proto-Norse or, according to Bernard Comrie, Late Common Germanic immediately following the "Proto-Germanic" stage. Proto-Germanic is itself descended from Proto-Indo-European (PIE).

Evolution of Proto-Germanic

The evolution of Proto-Germanic began with the separation of a common way of speech among some geographically proximate speakers of a prior language and ended with the dispersion of the proto-language speakers into distinct populations practicing their own speech habits. Between those two points many sound changes occurred.

Archaeological contributions

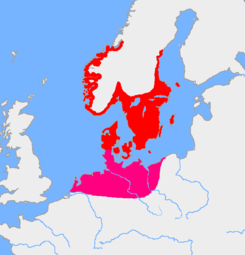

M

ap

of the Pre-Roman

Iron Age culture(s) associated with Proto-Germanic, c. 500 BC.

The magenta-colored area south of Scandinavia represents the Jastorf

culture.

ap

of the Pre-Roman

Iron Age culture(s) associated with Proto-Germanic, c. 500 BC.

The magenta-colored area south of Scandinavia represents the Jastorf

culture.

In one major theory of Andrev V Bell-Fialkov, Christopher Kaplonski, Wiliam B Mayer, Dean S Rugg, Rebeca W, Wendelken about Germanic origins, Indo-European speakers arrived on the plains of southern Sweden and Jutland, the center of the Urheimat or "original home" of the Germanic peoples, prior to the Nordic Bronze Age, which began about 4500 years ago. This is the only area where no pre-Germanic place names have been found. The region was certainly populated before then; the lack of names must indicate an Indo-European settlement so ancient and dense that the previously assigned names were completely replaced. If archaeological horizons are at all indicative of shared language (not a straightforward assumption), the Indo-European speakers are to be identified with the much more widely ranged Cord-impressed ware or Battle-axe culture and possibly also with the preceding Funnel-necked beaker culture developing towards the end of the Neolithic culture of Western Europe.

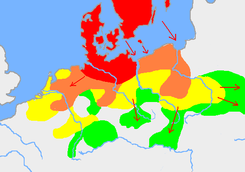

T

he

expansion of the Germanic tribes

750 BC – AD 1 (after the

Penguin Atlas of World History 1988):

he

expansion of the Germanic tribes

750 BC – AD 1 (after the

Penguin Atlas of World History 1988):

Settlements before 750BC

New settlements until 500BC

New settlements until 250BC

New settlements until AD 1

Proto-Germanic then evolved from the Indo-European spoken in the Urheimat region. The succession of archaeological horizons suggests that before their language differentiated into the individual Germanic branches the Proto-Germanic speakers lived in southern Scandinavia and along the coast from the Netherlands in the west to the Vistula in the east around 750 BC.[6]

Evidence in other languages

In some non-Germanic languages spoken in areas adjacent to Germanic speaking areas, there are loanwords believed to have been borrowed from Proto-Germanic. Some of these words are (with the reconstructed form in P-N): rõngas (Estonian) / rengas (Finnish) < *hrengaz (ring), kuningas (Finnish) < *kuningaz (king),[2] ruhtinas (Finnish) < *druhtinaz (lord), silt (Estonian) < *skild (tag, token), märk/ama (Estonian) < *mērke (to spot, to catch sight of), riik (Estonian) < *rik (state, land, commonwealth), väärt (Estonian) < *vaērd (worth), kapp (Estonian) / "kaappi" (Finnish) < *skap (chest of drawers; shelf)[citation needed]

Linguistic definitions

By definition, Proto-Germanic is the stage of the language constituting the most recent common ancestor of the attested Germanic languages, dated to the latter half of the first millennium BC. The post-PIE dialects spoken throughout the Nordic Bronze Age, roughly 2500–500 BC, even though they may have no attested descendants other than the Germanic languages, are referred to as "Germanic Parent Language", "pre-Proto-Germanic" or more commonly "pre-Germanic." By 250 BC, Proto-Germanic had branched into five groups of Germanic (two each in the West and the North, and one in the East).

In historical linguistics, Proto-Germanic is a node in the tree model; that is, if the descent of languages can be compared to a biological family tree, Proto-Germanic appears as a point, or node, from which all the daughter languages branch, and is itself at the end of a branch leading from another node, Proto-Indo-European. One of the problems with the node is that it implies the existence of a fixed language in which all the laws defining it apply simultaneously. Proto-Germanic, however, must be regarded as a diachronic sequence of sound changes, each law or group of laws only becoming operant after previous changes.

To the evolutionary history of a language family, a genetic "tree model" is considered appropriate only if communities do not remain in effective contact as their languages diverge. Early IE was computed to have featured limited contact between distinct lineages, while only the Germanic subfamily exhibited a less treelike behavior as it acquired some characteristics from neighbors early in its evolution rather than from its direct ancestors. The internal diversification of especially West Germanic is cited to have been radically non-treelike.

W. P. Lehmann considered that Jacob Grimm's "First Germanic Sound Shift", or Grimm's Law and Verner's Law, which pertained mainly to consonants and were considered for a good many decades to have generated Proto-Germanic, were pre-Proto-Germanic, and that the "upper boundary" was the fixing of the accent, or stress, on the root syllable of a word, typically the first. Proto-Indo-European had featured a moveable pitch accent comprising "an alternation of high and low tones" as well as stress of position determined by a set of rules based on the lengths of the word's syllables.

The fixation of the stress led to sound changes in unstressed syllables. For Lehmann, the "lower boundary" was the dropping of final -a or -e in unstressed syllables; for example, post-PIE *woyd-á > Gothic wait, "knows" (the > and < signs in linguistics indicate a genetic descent). Antonsen agreed with Lehmann about the upper boundary but later found runic evidence that the -a was not dropped: ékwakraz … wraita, "I wakraz … wrote (this)." He says: "We must therefore search for a new lower boundary for Proto-Germanic."

His own scheme divides Proto-Germanic into an early and a late. The early includes the stress fixation and resulting "spontaneous vowel-shifts" while to define the late he lists ten complex rules governing changes of both vowels and consonants.