Люпус-нефрит

.pdf

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Chapter 27 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Lupus Nephritis |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Figure 27.10 Effect of |

|

Effect of immunosuppressive treatment on chronic histologic damage in lupus nephritis |

|

immunosuppressive treatment on |

||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

chronic histologic damage in lupus |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

nephritis. Combined analysis from NIH |

|

8 |

|

Prednisone only |

|

|

8 |

Prednisone plus cytotoxic drug |

|

trials of prednisone plus cytotoxic agents |

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

versus prednisone alone. Change in |

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

6 |

|

|

|

|

6 |

|

|

|

|

chronicity index occurs (glomerular and |

index |

|

|

|

index |

|

|

|

|

interstitial fibrosis plus sclerosis) in |

||

4 |

|

|

|

4 |

|

|

|

|

individual patients, as shown by repeat |

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

chronicity |

|

|

|

|

chronicity |

|

|

|

|

|

biopsies 24–132 months apart. Patients |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

receiving prednisone alone show a steady |

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

2 |

|

|

|

|

2 |

|

|

|

|

increase in the chronicity index, whereas |

in |

|

|

|

|

in |

|

|

|

|

|

there is an insignificant change in |

0 |

|

|

|

0 |

|

|

|

|

chronicity index in those receiving a |

||

Change |

|

|

|

Change |

|

|

|

|

|||

–2 |

|

|

|

–2 |

|

|

|

|

therapies were given including intravenous |

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

cytotoxic drug in addition. Various cytotoxic |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

and oral cyclophosphamide; oral |

|

–4 |

|

|

|

|

–4 |

|

|

|

|

azathioprine; and oral azathioprine plus |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

cyclophosphamide. There was no |

|

0 |

33 |

66 |

99 |

132 |

0 |

33 |

66 |

99 |

132 |

difference in the data between any of |

|

|

Time interval (months) |

|

|

Time interval (months) |

|

these groups. |

||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

i.v. cyclophosphamide |

|

Oral cyclophosphamide |

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

Azathioprine and |

|

Azathioprine |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

cyclophosphamide |

|

|

|

|

|

dosage. Both azathioprine and cyclophosphamide almost certainly have a steroid-sparing effect. Azathioprine has only a very small oncogenic potential; pregnancy during maintenance azathioprine can be encouraged and is safe. Pancreatitis and hepatotoxicity are very rare. Long-term results as good or better than the best obtainable with cyclophosphamide by whatever route can be achieved using initial intravenous methylprednisolone and 12 weeks’ oral cyclophosphamide, followed by long-term combined azathioprine and corticosteroids. In practice a choice of cytotoxic agents is useful31. In the author’s view1,20 there is no evidence, as yet, that intravenous cyclophosphamide offers a better risk/benefit ratio in the long-term than azathioprine (Fig 27.11) and this suggestion is upheld in the only small controlled trial comparing the two treatments in the long term32.

Mycophenolate mofetil has been used in lupus nephritis during the past five years or so33, first in small series and then in larger controlled trials34, some of which are ongoing. Results have been encouraging, with results comparable to the best obtained using any of the regimens outlined above. Its precise role in the treatment of lupus nephritis remains to be determined, however, and long term results are not yet available. Nevertheless, it seems at the time of writing to present a viable and less toxic alternative cytotoxic agent in the long term, and it may be of use in treatment of acute lupus as well.

Chlorambucil has been advocated as maintenance treatment also, but it has never been subjected to any controlled trials in lupus nephritis and its gonadal effects and oncogenic potential are, if anything, greater than those of cyclophosphamide.

Cyclosporine might be expected to benefit patients with lupus because of its powerful effect on helper T-cell clonal expansion through inhibition of interleukin-2 synthesis (Chapter 85). Limited evidence suggests that a dose of 5 mg/kg/24 h (chosen to avoid nephrotoxicity) produces a good

Renal survival in lupus nephritis

Prednisolone and azathioprine

Prednisolone and i.v. cyclophosphamide

Cumulativepercent |

|

100 |

|

|

|

|

|

survival |

0 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

80 |

|

|

|

|

|

a |

|

0 |

24 |

48 |

72 |

96 |

120 |

|

|

|

|

Time (months) |

|

|

|

Cumulativepercent |

|

100 |

|

|

|

|

|

survival |

80 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

0 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

0 |

24 |

48 |

72 |

96 |

120 |

|

|

|

|

Time (months) |

|

|

|

Figure 27.11 Renal survival in lupus nephritis. (a) Renal survival in lupus nephritis in three series of patients treated with azathioprine and the NIH trial data for patients treated with i.v. cyclophosphamide; there was no statistical difference in the outcomes. (b) Renal survival in class IV lupus nephritis treated with azathioprine compared favorably with NIH data for i.v. cyclophosphamide. Again there is no statistical difference in the outcomes using the different treatment regimens at 0.05 level. All patients in all studies received background maintenence prednisolone treatment.

response in some patients although relapse often follows withdrawal of treatment. There is no effect in reducing anti-dsDNA

antibody levels. Cyclosporine does not appear to be useful in

367

Section 5

Glomerular Disease

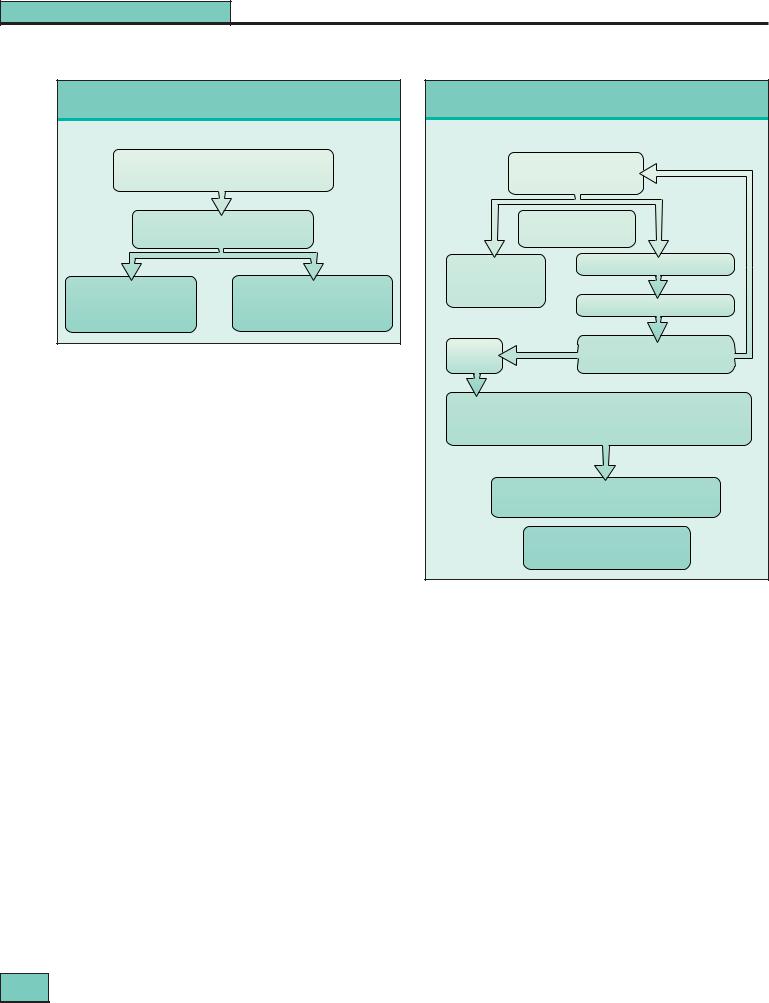

Maintenance treatment for mild lupus nephritis

Mild nephritis (defined in Figure 27.9)

Oral prednisolone 10–15 mg daily for 3–5 years azathioprine 2 mg/kg per day

|

Clinical and immunologic monitoring |

Remains |

Relapse/ |

quiescent |

exacerbation |

Taper prednisolone; change |

Biopsy |

|

If active histologic deterioration |

||

to alternate-day regimen; |

||

consider induction treatment |

||

further biopsy usually |

||

as for severe nephritis (Figure 27.9) |

||

unnecessary |

||

|

Figure 27.12 Maintenance treatment for mild lupus nephritis.

acute lupus but can have a role in the maintenance phase as a steroid-sparing agent and to reduce massive proteinuria35, for example in membranous lupus nephritis.

Intravenous immunoglobulin36,37 has been used with encouraging results in a number of small series, including those patients resistant to conventional treatment, and in one small controlled trial. Modification of anti-idiotype networks by the anti-idiotypic antibodies in the preparation is the most likely mode of action36. Various preparations and dosages have been used for periods up to 6 months or 1 year. Relapse after improvement is seen frequently. Transient decline in renal function may follow its use in nephrotic patients.

Newer forms of immunologic intervention

Patients with severe resistant lupus have been given total lymphoid irradiation. Results have been encouraging, with minimal requirements for subsequent immunosuppression. Even more radical approaches have been used in very resistant disease with major treatment side effects, including marrow ablation and reconstitution using stem cells38. These approaches are still experimental as are the newer immunologic strategies including the use of monoclonal antibodies and molecular blockers to interrupt specific elements of immune recognition39.

A summary of disease-specific maintenance treatment is given in Figures 27.12 and 27.13. General renoprotective measures, such as the use of angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors and lipid-lowering drugs, should be used in addition in long-term progressive lupus nephritis, especially if there is profuse proteinuria and hyperlipidemia.

Serologic tests in monitoring effects of specific treatment

While persisting anti-dsDNA antibody may be associated with subsequent relapses, a number of patients maintain elevated levels for years without relapse; and there is a fine balance between undertreatment and overtreatment. The main value of anti-dsDNA antibody levels is that normal

values usually permit safe reduction of treatment during the

368

Maintenance treatment for severe lupus nephritis

Severe nephritis (defined in Figure 27.9)

After 12 weeks, induction treatment

|

Prednisolone 10–15 mg/day |

Response |

||

|

|

|||

|

azathioprine 2 mg/kg day |

|

||

Quiescent |

Clinical and |

Relapse/declining |

||

for 3–5 years |

renal function |

|||

immunologic monitoring |

||||

|

|

|||

Stop azathioprine |

Biopsy if active histologic deterioration |

|||

Taper prednisolone |

|

|

||

using alternate-day |

|

|

||

regimes |

|

Continue maintenance treatment |

||

|

|

|||

Stop |

No |

Consider i.v. methylprednisolone |

||

|

||||

azathioprine |

improvement |

|

1 g × 3 |

|

i.v. Cyclophosphamide 0.75 g/m2 monthly for 6 months

•monitor white-cell count

•risk of gonadal toxicity (if cyclophosphamide used for induction)

•reduce dose if renal function reduced

No improvement unacceptable toxicity

Consider i.v. human IgG 400 mg/kg per day for 4–7 days then monthly for 6 months if response

Consider cyclosporine 2 mg/kg per day as additional steroid sparing agent especially if nephrotic

Figure 27.13 Maintenance treatment for severe lupus nephritis.

chronic phase. Likewise, complement concentrations are of limited value during the acute phase in severe nephritis; clinical and biochemical data are almost always sufficient.

When can treatments for lupus nephritis be stopped?

The goal of long-term management in patients with lupus nephritis is suppression of disease with minimum side effects of treatment. This balance is not easily achieved and requires close attention to detail in individual patients. Repeat renal biopsy may suggest whether a slow decline in renal function with proteinuria is the result of active nephritis, or of secondary sclerosis. Normal results from immunologic tests are a help in this distinction, but nevertheless in selected patients a repeat biopsy is a useful test to perform.

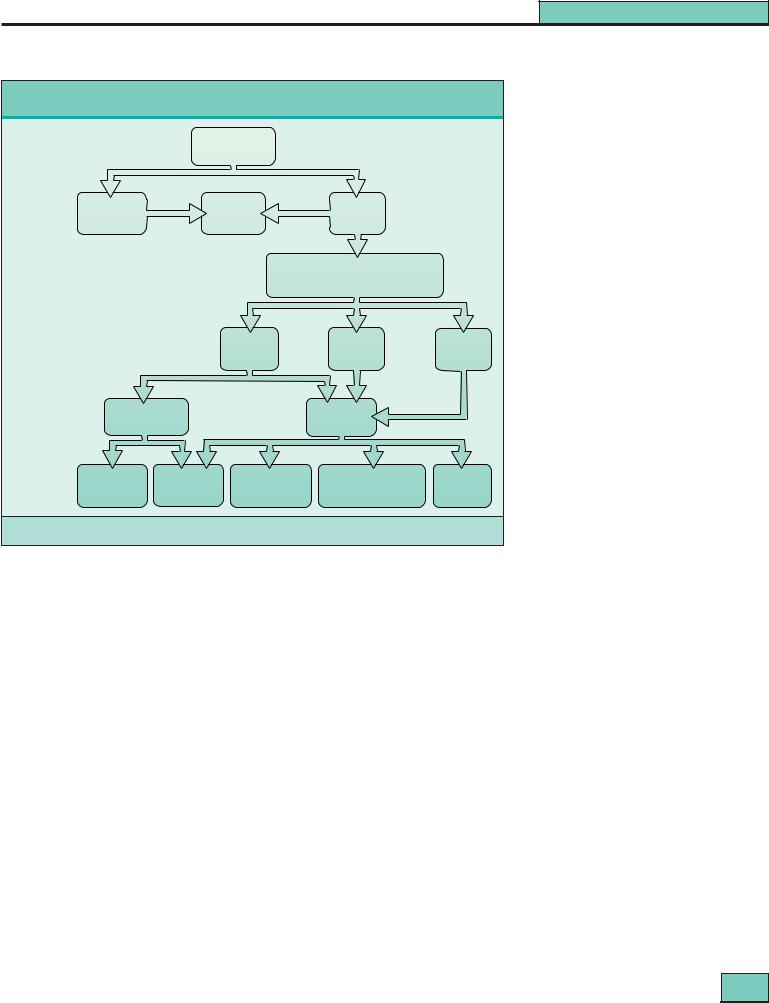

While occasionally patients will relapse more than 20 years from the onset of the disease when treatment is reduced, it is usually possible to stop treatment altogether after 5 years or so, even in patients with very severe lupus at onset, whose disease will have apparently ‘burnt out’, although some may relapse. Stable renal function, lack of proteinuria and normal immunologic tests are pointers to success. The very long-term outcome of a cohort of 110 patients first treated between 1963 and 1986 is shown in Figure 27.14.

|

|

|

|

|

|

Chapter 27 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Lupus Nephritis |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Figure 27.14 Most recent status of |

|

Most recent status of patients with lupus after very long term follow-up |

patients with lupus after very long- |

||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

term follow-up. A cohort of 110 patients |

|

|

|

|

|

|

observed between 1963 and 1986 (mean |

|

|

110 Patients |

|

age at diagnosis 15.4, range 10–32 |

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

years) (Adapted with permission from |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Bono, Cameron and Hicks40). |

|

40 (35%) |

9 |

|

9 |

70 (65%) |

|

Outcome |

|

|

18 |

|

||

Dead |

|

ESRD |

Alive |

|

||

|

|

|

||||

|

|

|

|

|

61 |

|

|

|

|

|

Alive with independent renal function |

|

|

Renal |

|

|

|

48 |

11 |

2 |

|

|

|

Reduced |

|||

function |

|

|

|

Normal |

Not known |

|

|

|

|

(4-CRF) |

|||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

23 |

|

|

|

25 |

|

Urine |

|

23 |

|

|

2 |

|

|

|

|

38 |

|

||

findings |

Normal urine |

|

|

Proteinuria |

|

|

|

11 |

12 |

5 |

28 |

3 |

2 |

Present |

11 |

17 |

|

28 |

3 |

2 |

No |

Prednisolone |

|

Prednisolone |

Prednisolone + |

||

treatment |

|

Unknown |

||||

treatment |

only |

|

+ azathioprine |

i.v. cyclophosphamide* |

||

|

|

|

||||

* No patient received this as induction treatment |

|

|

|

|

||

Antiphospholipid antibodies and thrombosis12

There is no evidence that prophylactic anticoagulation brings extra benefit even if the APA is of the IgG isotype, which is more likely to be of clinical significance than IgM APA. If thrombosis has occurred, therapy with warfarin is required as long as APA persists – disappearance of APA is uncommon. If IgG APA is present in high titer, the international normalized ratio must be maintained at 3.0 or above; re-thrombosis can occur at 2.0–2.5. Immunosuppression has little effect on APA. APA are associated also with second trimester abortions, and low-dose aspirin (75 mg/day) may be of benefit, although this has not been shown in controlled trials.

Other treatments

A number of other treatments have been used for lupus, mostly without overt nephritis, but have not made a major impact1.

Indomethacin has been used but in view of the fall in GFR with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and their potential for inducing interstitial nephritis, this has not proved popular. Antimalarials and androgens seem to be ineffective in lupus nephritis, either alone or as agents to reduce steroid dosage.

ω -3 unsaturated eicosapentanoic acid (EPA) has been shown to protect mice from lupus nephritis, with a reduction in antidsDNA antibody titers, while a high saturated-fat diet accelerates the disease. A controlled trial of EPA in human lupus showed favorable short-term effects on hematuria, blood lipids,

and hemostatic parameters; anti-dsDNA titers were not affected. No benefit has yet been shown on nephritis. Effects on hemostasis and lipids are particularly attractive in view of the accelerated vascular disease reported in young women with lupus, which is a major cause of late morbidity and mortality.

Complications of lupus and its treatment1,40–42

Sepsis is the commonest early complication of treated lupus, and is related to the total dosage of corticosteroids and cyclophosphamide, but not azathioprine40,41. Infections are also more common in untreated lupus. Herpes zoster is particularly common in younger patients; early treatment with acyclovir should always be given to avoid dissemination. Pyogenic meningitis can be a major problem and Cryptococcus should be excluded in any lupus patients with meningitis. The C-reactive protein concentration is useful (but not specific) in distinguishing relapse of lupus from infection, since there is usually only a minor rise with exacerbations of disease. Bacterial endocarditis is rare but also presents obvious problems in diagnosis. With improvements in the survival of patients with lupus, accelerated atherogenesis has emerged as a major cause of later mortality. Myocardial infarction has been reported in very young patients in the absence of vasculitis. Possible risk factors for atheroma in lupus include hyperlipidemia, corticosteroids and hypertension even in children, and in a minority, the added vascular risks of

ESRD42.

369

Section 5

Glomerular Disease

Ischemic necrosis of bone is a common complication, affecting 15–20% of patients. Total corticosteroid dosage is the predominant risk factor, but it may present in patients who have never received corticosteroids, possibly as a result of microthromboses in association with APA. The femoral head is the commonest site of involvement in adults; in children it is the femoral condyle. Almost any other bone site may be involved, the next most frequent being the humeral head, the border of the scapula, and the carpus or tarsus. In some unfortunate patients, multiple sites may be involved. Osteoporosis1, as judged by X-ray densitometry is common in Caucasian women treated long-term with corticosteroids for lupus (~40%), but clinical fractures are rare (3% in our own long-term series40).

The incidence of neoplasia is modestly increased in lupus. Risk factors are the immune dysregulation present in lupus and the added effect of chronic immunosuppression. Either might be mediated by direct damage to chromosomes, or by facilitation of oncogenic viruses. Lymphomas, including the intracerebral site, are the principal form of tumor noted. Carcinoma of the cervix is commoner also, even in patients who have not received cytotoxic therapy.

Growth retardation is inevitable in children and adolescents treated long-term with corticosteroids. The main correlation is with the duration of daily corticosteroid treatment, emphasizing the need to use alternate-day corticosteroids wherever possible in children and adolescents.

Pancreatitis is a rare but well-known complication of treated lupus. Lupus itself, corticosteroid therapy, and perhaps also azathioprine are all capable of inducing the disease.

Cataracts are frequent after years of prednisolone treatment, affecting 20–30% of patients. They are usually symptomless, although occasionally lens removal and replacement may be necessary. The procedure is safe even in the presence of immunosuppression. Steroid-induced diabetes mellitus has been described although it is significantly less common than following transplantation. Raised intracranial pressure may appear and complicate yet further neurologic and psychiatric assessment. Proximal myopathy is underdiagnosed and a Cushingoid appearance and hirsutism are common, forming a major disincentive for adolescent girls and young women to take corticosteroids, compliance in this major group of patients therefore being poor. This may, on occasion, lead to relapses, with complications from untreated disease and further acute treatment.

End-stage renal disease and renal replacement therapy43,44

Today, no more than 10–15% of patients with lupus develop ESRD40, and lupus provides only 1–2% of all patients with ESRD. Many patients have inactive disease by the time they reach ESRD but another group develop irreversible renal failure quite rapidly, may have active disease and suffer a higher mortality and morbidity.

Patients with ESRD from lupus nephritis will sometimes show recovery of renal function sufficient to allow dialysis to be stopped, in some cases indefinitely. Thus, one should not rush to renal transplantation in patients with lupus, but consider a year or two on dialysis first. A renal biopsy may help to determine the reversibility of the renal disease.

Some patients continue to require immunosuppression after they have reached ESRD; usually prednisolone alone suffices. Nevertheless, survival of lupus patients on dialysis compares favorably with outcome for other primary renal diseases and patients with lupus make good candidates for dialysis, whether CAPD or hemodialysis, apart from susceptibility to thrombosis of vascular access28. This is related in some cases to APA, but some patients have Raynaud’s phenomenon with poor peripheral perfusion and veins may be small and difficult to use for successful arteriovenous fistulae.

TRANSPLANTATION

Transplantation43,44 in lupus (including from living donors) can be performed with only a few extra precautions being taken compared with recipients in other categories. Crossmatching donors with lupus patients may be difficult, because their sera may contain anti-lymphocyte autoantibodies. These are usually of IgM isotype, of low affinity, react with the common leukocyte CD45 antigen and present few problems. Some however are of IgG isotype, and so will register in conventional cross-matches but their target antigens, even if they include MHC antigens, are not allospecific and they do not affect graft outcome.

As is the case during dialysis, thrombosis may be a problem post-transplantation, especially in patients with APA. Both renal transplant arterial and venous thrombosis have been reported. Anticoagulation should be considered in patients with circulating APA of IgG isotype in high titers. Lupus disease activity lessens post-transplant, presumably because of the immunosuppressive regimens used.

The striking feature of transplantation in lupus remains the very low rate of recurrence of lupus nephritis44, even in patients with active disease at the time of receiving a transplant. The incidence is no more than 1 : 100, and even in those in whom recurrence has been clearly identified, it very rarely causes graft loss. In many reports of supposed recurrence, although electron-dense immune aggregates were present in glomeruli of the allograft, glomerular IgG – the hallmark of lupus nephritis – was not detected.

Immunosuppression usually does not need to be modified in patients with lupus, although cyclosporine monotherapy is best avoided because this drug is not a powerful suppressant of lupus and relapse has been described in this context. There is no difference in the number and severity of rejections in recipients with lupus compared with recipients in other categories and, with current immunosuppressive regimens, there seems to be no higher incidence of infections.

370 |

Chapter 27

Lupus Nephritis

REFERENCES

1.Cameron JS. Systemic lupus erythematosus. In: Nielson EG, Couser WG, eds. Immunologic Renal Disease, 2nd edition. Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven; 2001:1057–104.

2.Wallace DH, Hahn BH. Dubois’ lupus erythematosus, 4th edn. Baltimore: Lea & Febiger;1993.

3.Lewis EJ, Schwartz MM, Korbet SM (eds) Lupus nephritis. Oxford University Press, Oxford 1999.

4.Ruiz-Arastorza G, Khamashta M, Castellino G, Hughes GRV. Systemic lupus erythematosus. Lancet. 2001;357:1027–32.

5.Muehrcke RC, Kark RM, Pirani CL, Pollak VE. Lupus nephritis: a clinical and pathological study based on renal biopsies. Medicine (Baltimore).1957;36:1–146.

6.Hahn BH. Antibodies to DNA. N Engl J Med. 1998;338:1359–68.

7.Davidson A, Diamond B. Autoimmune diseases. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:340–50.

8.Goodnow CC. Pathways for self-tolerance and the treatment of autoimmune diseases. Lancet. 2001;357:2115–21.

9.Cameron JS. Clinical manifestations of lupus nephritis. In Lewis EJ, Schwartz MM, Korbet SM (eds) Lupus nephritis. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1999:159–84.

10.De Arriba G, Velo M, Barrio V, et al. Association of interstitial lupus cystitis with systemic lupus erythematosus. Clin Nephrol. 1992;39: 287–8.

11.West SG. Neuropsychiatric lupus. Rheum Clin N Am. 1994;20: 129–58.

12.Kashgarian M. Lupus nephritus: lessons from the path lab. Kidney Int. 1994;45:928–38.

13.Asherson RA, Cervera R, Piette J-C, et al. The antiphospholipid syndrome. Boca Raton: CRC Press; 1996.

14.Hill GS, Delahousse M, Nochy D, et al. Proteinuria and tubulointerstitial lesions in lupus nephritis. Kidney Int. 2001;60:1893–903.

15.Appel GB, Pirani CL, D’Agati V. Renal vascular complications of systemic lupus erythematosus. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1994;4: 1499–515.

16.Ropes MW. Observations on the natural history of disseminated lupus erythematosus. Medicine (Baltimore). 1964;43:387–91.

17.Donadio JV, Hart GM, Bergstralh EJ, et al. Prognostic determinants in lupus nephritis: a long-term clinicopathologic study. Lupus. 1995;4:109–15.

18.Gruppo Italiano per lo Studio della Nefrite Lupica (GISNEL). Lupus nephritis: prognostic factors and probability of maintaining life-supporting renal function 10 years after the diagnosis. Am J Kidney Dis. 1992;19:473–9.

19.Adu D. The evidence base for the treatment of lupus nephritis in the new millennium. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2001;16:1536–8.

20.Cameron JS. What is the role of long-term cytotoxic agents in the treatment of lupus nephritis? J Nephrol. 1993;6:172–6.

21.Donadio JV, Glassock RJ. Immunosuppressive drug therapy in lupus nephritis. Am J Kidney Dis. 1993;21:239–50.

22.Lewis EJ, Hunsicker LG, Lan S-P, et al. for the lupus nephritis collaborative study group. A controlled trial of plasmapheresis therapy in severe lupus nephritis. N Engl J Med. 1992;326:1373–9.

23.Felson DT, Anderson J. Evidence for the superiority of immunosuppressive drugs and prednisone over prednisone alone in lupus nephritis. N Engl J Med. 1984;311:1528–33.

24.Bansal VK, Beto JA. Treatment of lupus nephritis: a meta-analysis of clinical trials. Am J Kidney Dis. 1997;29:193–9.

25.Balow JE, Austin HA, Muenz LR, et al. Effect of treatment on the evolution of renal abnormalities in lupus nephritis. N Engl J Med. 1984;311:491–5.

26.Austin HA III, Klippel JH, Balow JE, et al. Therapy of lupus nephritis. Controlled trial of prednisone and cytotoxic drugs. N Engl J Med. 1986;314:614–19.

27.Steinberg AD, Steinberg SC. Long-term preservation of renal function in patients with lupus nephritis receiving treatment that includes cyclophosphamide versus those treated with prednisolone alone. Arthritis Rheum. 1991;34:945–50.

28.Boumpas DT, Austin HA III, Vaughan EM, et al. Risk for sustained amenorrhea in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus receiving intermittent pulse cyclophosphamide therapy. Ann Intern Med. 1993;119:366–9.

29.Ioannidis JPA, Boki KA, Katsordia ME, et al. Remission, relapse, and re-remission of proliferative lupus nephritis treated with cyclophosphamide. Kidney Int. 2000;57:258–64.

30.Illei GG, Austin HA, Crane M, et al. Combination therapy with pulse cyclophosphamide plus pulse methylprednisolone improves long-term outcome without adding toxicity in patients with lupus nephritis. Ann Intern Med. 2001;135:296–8.

31.Ponticelli C. Treatment of lupus nephritis: the advantages of a flexible approach. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 1997;12:2057–9.

32.El-Fattah M, El-Tayeb M, Abd El-Kader A, et al. Intravenous pulse cyclophosphamide versus sequential therapy with azathioprine in treatment of severe lupus nephritis: a prospective study. Afr J Nephrol. 2000;4:17–24.

33.Adu D, Cross J, Jayne DRW. Treatment of systemic lupus erythematosus with mycophenolate mofetil. Lupus. 2001;10:203–8:

34.Chan TMS, Li FK, Tang CSO, et al. for the Hong Kong-Guangzhou nephrology study group. Efficacy of mycophenolate mofetil in patients with diffuse proliferative lupus nephritis. N Engl J Med. 2000;343:1156–62.

35.Tam LS, Li EK, Leung KC, et al. Long-term treatment of lupus nephritis with cyclosporin A. Q J Med. 1998;91:573–80.

36.Kazatchkine MD, Kaveri SV. Immunomodulation of autoimmune and inflammatory diseases with intravenous immune globulin. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:747–55.

37.Rauova L, Lukac J, Levy Y, et al. High-dose intravenous immunoglobulins for lupus nephritis - a salvage immunomodulation. Lupus. 2001;10:209–13.

38.Traynor AE, Schroeder J, Rosa RM, et al. Treatment of severe systemic lupus erythematosus with high-dose chemotherapy and haemopoietic stem-cell transplantation: a phase I study. Lancet. 2000;356:701–7.

39.Balow JE, Boumpas DT, Austin HA III. New prospects for treatment of lupus nephritis. Semin Nephrol. 2000;20:32–9.

40.Bono L, Cameron JS, Hicks JA. The very long-term prognosis and complications of lupus nephritis and its treatmernt. Q J Med. 1999;92:211–18.

41.Ginzler E, Diamond H, Kaplan D, et al. Computer analysis of factors influencing frequency of infection in systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 1978;21:37–44.

42.Font J, Ramos-Casals M, Cervera R, et al. Cardiovascular risk factors and the long-term outcome of lupus nephritis. Q J Med. 2001;94:19–26.

43.Nossent HC. End-stage renal disease in the patient with SLE. In Lewis EJ, Schwartz MM, Korbet SM. Lupus nephritis. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1999:284–304.

44.Thervet E, Anglicheau D, Legendre C. Recent issues concerning renal transplantation in systemic lupus erythematosus. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2001;16:12–14.

371 |