American_Literature_Book_unit3

.pdf

Unit 3

ROMANTICISM AND THE AMERICAN

RENAISSANCE 1820 – 1865

It does not follow because many books are written by persons born in America that there exists an American literature. Books which imitate or represent the thought and like of Europe do not constitute an American literature. Before such can exist, an original idea must animate this nation and fresh currents must call into life fresh thoughts along its shores.

Margaret Fuller

American Romanticism coincides chronologically with European Romanticism. The longing for harmonious personality (Cooper, Chateaubriand), the search for Truth in Beauty (Poe, Keats), the perception of “the world in a grain of sand and eternity in an hour” (Melville, Blake) paralleled each other. But the Europeans had many century old traditions, while the American Romantic writers had to replace the printer with the writer, and persuade their countrymen that literature was as honorable an occupation as corn harvesting. On the other hand there were all the basic requirements for an independent national literature in America: enthusiastic writers, attractive subjects, an increasing number of printing presses, book stores, schools and libraries.

z Define Romanticism

as a literary movement. Which representatives of Romanticism in English and other literature do you known?

zWhat were the leading genres for the Romanticists?

Kindered Spirits, 1849

32

The American pioneer Daniel Boone guiding the new settlers from Virginia through the Cumberland Gap into Kentucky

At the beginning of the 19th century American cultural and intellectual life was framed by the ever-expanding southern and western frontiers, culminating in 1853, when the continental boundaries of the US were completed. Geographical expansion came to be part of broadening the nation’s literary horizon. Aspiring literary minds turned to personal accounts of life west of the Allegheny Mountains. Widely publicized literary works by W. Irving and J. F. Cooper attracted still greater attention to the frontier, especially in coastal cities of the Atlantic. But the settlers’ literary interests centered on practical books such as various guides to farming, medicine, agriculture, horsemanship and everyday problems.

A controversial aspect of American life was the displacement of a large number of Indians as white settlers conquered the wilderness. Even though the white newcomers used the Indians’ knowledge of agriculture and medicine for their own benefit, they wrote books about Native Americans like The American Savage: How He May Be Tamed by the Weapons of Civilization. Most readers were still fascinated with captivity narratives, a literary genre exemplified in the 17th century by A Narrative of the Captivity and Restoration of Mrs. Mary Rowlandson (1682). Eventually, they gave way to the heroic deeds of the legendary frontier figures like Daniel Boone or Davy Crockett. Their popularity paved the way for the even more celebrated tradition of the tall tale and local color fiction later in the 19th century.

Davy Crockett’s Legendary Shooting Match with Mike Fink

Mike was a boatman on the Mississip, but he had a little cabbin on the head of the Cumberland, and a horrid handsome wife, that loved him the wickedest that ever you see. Mike only worked enough to find his wife in rags, and himself in powder, and lead, and whiskey, and the rest of the time he spent in nocking over bar and turkeys, and bouncing deer, and sometimes drawing a lead on an injun. So one night I fell in with him

in the woods, where him and his wife shook down a blanket for me in his wigwam. In the morning sez Mike to me, “I’ve got the handsomest wife, and the fastest horse, and the sharpest shooting iron in all Kentuck, and if any man dare doubt it, I’ll be in his hair quicker

than hell could scorch a feather.” This put my dander up, and sez I, “I’ve nothing to say agin your wife, Mike, for it can’t be denied she’s a shocking handesome woman, and Mrs. Crockett’s

UNIT

3

ROMANTICISM AND THE AMERICAN RENAISSANCE 1820 – 1865

33

in Tennessee, and I’ve got no horses. Mike, I don’t exactly like to tell you you lie about what you say about your rifle, but I’m d—d 1 if you speak the truth, and I’ll prove it. Do you see that cat sitting on the top rail of your potato patch, about a hundred and fifty yards off? If she ever hears agin, I’ll be shot if it shan’t be without ears.

1833 (11)

Still, the quest for truly national literature remained a topical issue. The North American Review (founded in 1815), the first journal that printed exclusively American material, called for American writers to put an end to imitating British and continental stereotypes, and by the end of the 1820s, Americans could celebrate the publication of Washington Irving’s Sketch Book (1819), William Cullen Bryant’s Poems (1821), some of James Fenimore Cooper’s Leather-Stocking Tales, Edgar Allan Poe’s Tamerlane and other Poems (1827), and Noah Webster’s American Dictionary (1828). The fame of the Knickerbocker School (J. K. Paulding, J. H. Payne, W. Irving, and briefly W. C. Bryant and J. F. Cooper), added brilliance to the American literary scene and made New York the national literary capital. It was also the time when many literary clubs were founded. In 1824, Cooper, together with William Bryant, Samuel F. B. Morse, and Thomas Cole, the English born painter, organized the Bread and Cheese Club. Among the members of the Saturday Club were Emerson, J. R. Lowell, H. W. Longfellow, O. W. Homes and the historians John L. Motley and William H. Prescott. The Authors Club united dominant magazine editors of the early 19th century.

“The literature of the United States is a subject of the highest interest to the civilized world,” wrote Cooper, “for when it does begin to be felt, it will be felt with a force, a directness, and a common sense in its application, that has never yet been known.... I think the time for the experiment is getting near.” As if according to this prophesy, Irving adapted European literary heritage to American settings, Cooper turned Natty Bumppo into the American archetype of individual freedom and self-reliance, which served the fictional predecessor of countless mountain men and wilderness cowboys. Though they were writing in Europe, these two writers paved the way for the great flowering of American literature.

In 1823, knowing that the British Navy would be involved in defending Latin America from the Holy Alliance of Russia, Prussia and Austria, President Monroe pronounced his refusal to tolerate any further extension of European domination in the Americas: “The American continents... are henceforth not to be considered as subjects for future colonization by any Euroupean powers...”

The Monroe Doctrine expressed solidarity with the newly independent republics of Latin America. It was the time, when democracy, with its good and bad, did flourish, when customs and people themselves were changing. Hair wigs and waistcoats were being replaced by loose overalls. The sewing machine, telegraph, and the assembly line were invented. It was the time of the Second Great Awakening and liberating of the church, when the Baptists, Methodists, Protestants, Mormons and the Seventh Day Adventists appeared. America was becoming a very diverse nation, and the times, when only one path to God was officially recognized, seemed far back in the past. It was also the time when the first large estates, accompanied by trickery and corruption, came onto the scene. The Americans may have somewhat forgotten the testament of the first settlers, but the providence idea was still glowing and it acquired a new form — pioneer-frontiersman grew into the American Prometheus, — and the wilderness path to the Appalachians turned into the road.

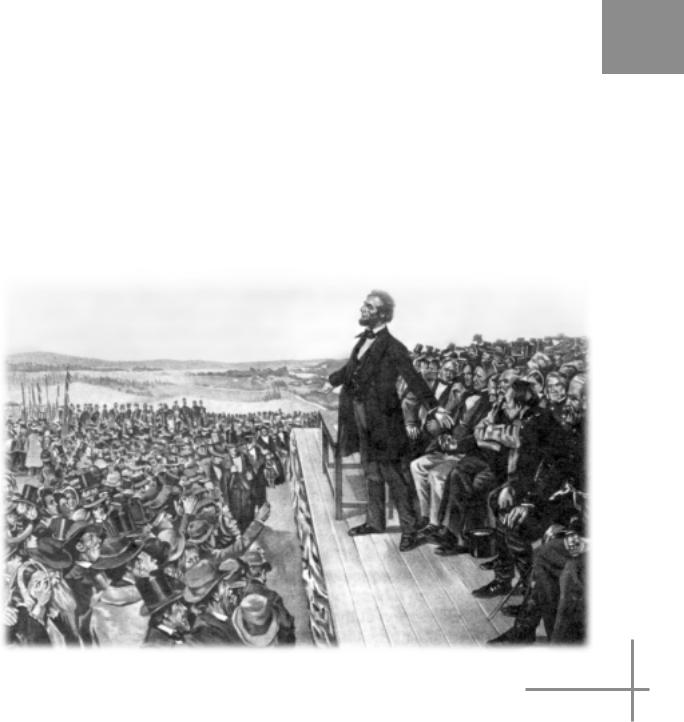

The American Renaissance (1836-1865) was marked by two turmoils, the Panic of 1837 and the Civil War, as well as by two presidents Andrew Jackson and Abraham Lincoln. The former, from the backwoods of Tennessee, seemed a prosaic leader, falling off from

1damned, darned adj., interj. both swearing or taboo words, are used as an exclamation, or a sound expressing an emotional reaction rather than any particular meaning

34

the daring age of the founding Fathers. The latter ruled with unprecedented authority during a long and brutal Civil War. An “idiomatic Western genius,” as Whitman called him, Lincoln left behind a legacy of his spoken and written prose, — colloquial, expressive, modest and always to the point. For 30-year-old Mark Twain, Lincoln’s style proved that simplicity was one of the secrets of eloquence.

Address at Gettysburg, pennsylvania

Four score and seven-years ago our fathers brought forth on this continent, a new nation, conceived in Liberty, and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal.

Now we are engaged in a great civil war, testing whether that nation, or any nation so conceived and so dedicated, can long endure. We are met on a great battle-field of that war. We have come to dedicate a portion of that field, as a final resting place for those who here gave their lives that that nation might live. It is altogether fitting and proper that we should do this.

But, in a larger sense, we can not dedicate — we can not consecrate — we can not hallow

— this ground. The brave men, living and dead, who struggled here, have consecrated it, far above our poor power to add or detract. The world will little note, nor long remember what we say here, but it can never forget what they did here. It is for us the living, rather, to be dedicated here to the unfinished work which they who fought here have thus far so nobly advanced. It is rather for us to be here dedicated to the great task remaining before us — that from these honored dead we take increased devotion to that cause for which they gave the last full measure of devotion — that we here highly resolve that these dead shall not have died in vain — that this nation, under God, shall have a new birth of freedom — and that government of the people, by the people, for the people, shall not perish from the earth.

(19)

Abraham Lincoln (1809-1865) commemorates the victims of the battle at Gettysberg.

UNIT

3

ROMANTICISM AND THE AMERICAN RENAISSANCE 1820 – 1865

35

Transcendentalists. George Ripley in his Letter to the Church in Purchase Street

(1840) wrote: “There is a class of persons who desire a reform in the prevailing philosophy of the day. These are called Transcendentalists, because they believe in an order of truths which transcends the sphere of the external sense. Their leading idea is the supremacy of mind over matter. Hence they maintain that the truth of religion does not depend on tradition, nor historical facts, but has a faithful witness in the soul.” Having absorbed the philosophical essence of Kant, Goethe, Coleridge, Wordsworth, Carlyle and other European thinkers, Ralph Waldo Emerson, the Reverend Theodore Parker, Henry David Thoreau, and Margaret Fuller declared in the 1830s that God could be known through Nature and man’s own soul, not only in church. As if in support of this idea H. D. Thoreau spent more than two years in a cabin at Walden Pond in isolation in the midst of natural beauty.

This movement had a very loose structure. Founded as an informal club in 1836, it generated The Dial, a quarterly journal (1840-1844). Though it was often ridiculed for what was considered excessive fantasies, it inspired two experiments of cooperative living and high thinking: Brook Farm (1841-1847) and Fruitlands (1843), both near Boston. The Transcendentalists opposed materialism, rationalism, conformity, the stereotypes of religion and society, and tried to erect the temple of the Living God in Man’s soul.

Abolitionism. It was also the time when antislave tensions were running high. To the Southerners, slavery was as natural a condition as their English speech. The North opposed slavery and its extension into the Western regions. To add to the plight of the slaves, after the 1830s, slave owners began to employ professional overseers, whose status depended on their ability to extract a maximum amount of work from slaves.

An earlier antislavery movement had its important victory in 1808 when Congress abolished the slave trade with Africa. The early 1830s saw the uncompromising actions of William Lloyd Garrison who wrote in the first issue of The Liberator: ”I shall strenuously contend for the immediate enfranchisement of our slave population... On this subject I do not wish to think, or speak, or write with moderation... I am in earnest — I will not equivocate — I will not excuse — I will not retreat a single inch, AND I WILL BE HEARD.” He was joined by the powerful voice of Frederick Douglass, an escaped

slave and the eloquent editor of the abolitionist weekly,

Northern Star, and author of The Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass (1845), and later by Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin (1851).

The cluster of events around 1849 contributed to the morality of trade and wild luck. The discovery of California gold in the Sacramento Valley in 1848 profoundly changed the population spread, railroad connections, and exposed much mercantilism, greed, desire for quick enrichment. It stamped the nation with something more than Yankee luck, and was seen as an event of Providence, a confirmation of national favor and mission.

36

Expanding Your Knowledge

PERSONAL RESPONSE

1.What kind of literature was in high demand at the frontier?

2.What literary schools were set up in the first quarter of the 19th century?

3.Briefly characterize the speech delivered by Abraham Lincoln.

4.How did the Transcendentalists influence the public mind?

5.Name the leaders of the abolitionist movement.

6.What was the national impact of the Gold Rush in 1849?

7.Complete the sentences:

a)Books about Native Americans …

b)By the end of the 1820s America could celebrate …

c)The contemporary inventions were …

d)Lincoln was called … by Whitman.

e)The Transcendentalists did not accept …

f)The Civil War was fought between ...

g)The morality of trade and wild luck was boosted by …

PERSONAL WRITING

zMake an additional redearch on one of the authors mentioned in this unit and write about him/her.

zFind an original work by an American Romanticist, and analyze it in an essay.

CROSSWORD

With the help of the dictionary and one letter provided, fill in the crossword. Try to revive the original context of the words.

1.The theory, practice, and style of romantic art, music, and literature of the late 18th and early 19th centuries, usually opposed to classicism.

2.Partially cleared, sparsely populated forests.

3.A mental attitude or point of view.

4.16th president of the U.S. His fame rests on his success in saving the Union in the Civil

5. |

War (1861-1865). |

|

1 |

A person who revises books, |

2 |

||

|

periodicals, films etc. |

|

|

6. |

Make a prisoner of, overcome |

3 |

|

7. |

To force one to leave home |

|

|

|

|

||

|

or country. |

|

4 |

8. |

A standardized image or idea |

|

5 |

|

shared by all members of a |

|

|

|

|

|

|

9. |

social group. |

|

6 |

The edge of the settled area |

|

7 |

|

|

of a country; borderline. |

|

|

10. Anything that has been |

8 |

|

|

|

transmitted from the past or |

9 |

|

|

handed down by tradition. |

|

|

11. Member of a primitive tribe |

|

10 |

|

|

living by hunting or fishing; |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

wild man. |

|

11 |

12. To increase in size or area; |

|

|

|

add to or enlarge. |

12 |

|

UNIT

3

ROMANTICISM AND THE AMERICAN RENAISSANCE 1820 – 1865

37

WASHINGTON IRVING

I scarcely look with full satisfaction on any [of my works]. I often wish I could have twenty years more, to take them down from the shelf one by one, and write them over.

Washington Irving

zHave you ever traveled to wondrous places that strongly impressed your imagination? How did it enrich your outlook?

zWhat feature of character does the quotation reveal?

Both home and abroad Washington Irving is considered the first truly American man of letters, whose stories entered school and university curricula during his lifetime. His best known and first American short stories The Legend of Sleepy Hollow and Rip Van Winkle are still among the favorite classics.

The youngest of 11 children of a cordial mother and a more

domineering father, Washington Irving (April 3, 1783, New York City — Nov. 28, 1859, Tarrytown, New York) was brought up in an easy-going and carefree atmosphere. A story has it that George Washington himself met Irving and blessed him. It could have been the reason for writing the monumental biography The Life of George Washington later in his life. Irving avoided a college education, but studied law himself, mostly in the office of Josiah Hoffman, with whose daughter he soon fell in love.

In 1802, Irving produced a number of satirical essays under the signature of Jonathan Oldstyle, Gent., made several trips up the Hudson river, another into Canada for his health. He also took an extended tour of Europe in 1804-1806. Later, together with other enthusiasts, he published satirical pamphlets on the faults of New York society in a periodical entitled Salmagundi, which still remains a guide to the social environment of the 1810s. Irving’s

History of New York by Diedrich Knickerbocker (1809) is a satire of the Dutch regime in New York, and one of the earliest humorous histories. The name was adopted for the first American school of writers, the “Knickerbocker Group,” with Irving as the leader.

In 1815, after his mother’s death, Irving went to Liverpool to attend to the interests of his brothers’ hardware firm. On the way there he met Sir Walter Scott in London, who encouraged him in his creative efforts. The result was The Sketch Book of Geoffrey Crayon, Gent. (18191820), a collection of stories and essays that mix satire and eccentricity with fact and fiction.

Most of its 27 pieces relate Irving’s impressions of England, but six stories deal with American subjects. Though under the heavy influence of German folktales, they are already concerned with American life in a Dutch settlement after the War of Independence. The overwhelming success of The Sketch Book reassured Irving that he could live by his pen, and in 1822 he produced Bracebridge Hall, a sequel to The Sketch Book.

In 1826, he accepted an invitation to join the American diplomatic mission in Spain, where he wrote Columbus (1828). Meanwhile, Irving had become absorbed in the legends of the Moorish past and wrote A Chronicle of the Conquest of Granada (1829) and The Alhambra (1832), a Spanish counterpart of The Sketch Book.

After a 17-year stay in Europe Irving was warmly welcomed to New York in 1832 as the first American author of international acclaim. Irving spent the remainder of his life at his home, “Sunnyside,” in Tarrytown, on the Hudson River, where he devoted himself to literary pursuits.

38

Rip Van Winkle

1Whoever has made a voyage up the Hudson must remember the Kaatskill mountains. They are a dismembered branch of the great Appalachian family, and are seen away to the west of the river, swelling up to a noble height, and lording it over the surrounding country. Every change of season, every change of weather, indeed, every hour of the day, produces some change in the magical hues and shapes of these mountains, and they are regarded by all the good wives, far and near, as perfect barometers. When the weather is fair and settled, they are clothed in blue and purple, and print their bold outlines on the clear evening sky; but, sometimes, when the rest of the landscape is cloudless, they will gather a hood of gray vapors about their summits, which, in the last rays of the setting sun, will glow and light up like a crown of glory.

2At the foot of these fairy mountains, the voyager may have descried the light smoke curling up from a village, whose shingle-roofs gleam among the trees, just where the blue tints of the upland melt away into the fresh green of the nearer landscape. It is a little village, of great antiquity, having been founded by some of the Dutch colonists; in the early times of the province, just about the beginning of the government of the good Peter Stuyvesant, (may he rest in peace!) and there were some of the houses of the original settlers standing within a few years, built of small yellow bricks brought from Holland, having latticed windows and gable fronts, surmounted with weather-cocks.

3In that same village, and in one of these very houses (which, to tell the precise truth, was sadly time-worn and weather-beaten), there lived many years since, while the country was yet a province of Great Britain, a simple good-natured fellow, of the name of Rip Van Winkle. He was a descendant of the Van Winkles who figured so gallantly in the chivalrous days of Peter Stuyvesant, and accompanied him to the siege of Fort Christina. He inherited, however, but little of the martial character of his ancestors. I have observed that he was a simple good-natured man; he was, moreover, a kind neighbor, and an obedient henpecked husband. Indeed, to the latter circumstance might be owing that meekness of spirit which gained him such universal popularity; for those men are most apt to be obsequious and conciliating abroad, who are under the discipline of shrews at home. …

4Rip’s sole domestic adherent was his dog Wolf, who was as much hen-pecked as his master; for Dame Van Winkle regarded them as companions in idleness, and even looked upon Wolf with an evil eye, as the cause of his master’s going so often astray. True it is, in all points of spirit befitting an honorable dog, he was as courageous an animal as ever scoured the woods — but what courage can withstand the everduring and all-besetting terrors of a woman’s tongue? The moment Wolf entered the house his crest fell, his tail dropped to the ground, or curled between his legs, he sneaked about with a gallows air, casting many a sidelong glance at Dame Van Winkle, and at the least flourish of a broomstick or ladle, he would run to the door with yelping precipitation.

5Times grew worse and worse with Rip Van Winkle as years of matrimony rolled on; a tart temper never mellows with age, and a sharp tongue is the only edged tool that grows keener with constant use. For a long while he used to console himself, when driven from home, by frequenting a kind of perpetual club of the sages, philosophers, and other idle personages of the village, which held its sessions on a bench before a small inn, designated by a rubicund portrait of His Majesty George the Third. …

UNIT

3

ROMANTICISM AND THE AMERICAN RENAISSANCE 1820 – 1865

39

6Poor Rip was at last reduced almost to despair; and his only alternative, to escape from the labor of the farm and clamor of his wife, was to take gun in hand and stroll away into the woods. Here he would sometimes seat himself at the foot of a tree, and share the contents of his wallet with Wolf, with whom he sympathized as a fellow-sufferer in persecution. “Poor Wolf,” he would say, “thy mistress leads thee a dog’s life of it; but never mind, my lad, whilst I live thou shalt never want a friend to stand by thee!” Wolf would wag his tail, look wistfully in his master’s face, and if dogs can feel pity I verily believe he reciprocated the sentiment with all his heart.

7In a long ramble of the kind on a fine autumnal day, Rip had unconsciously scrambled to one of the highest parts of the Kaatskill mountains. He was after his favorite sport of squirrel shooting, and the still solitudes had echoed and reechoed with the reports of his gun. Panting and fatigued, he threw himself, late in the afternoon, on a green knoll, covered with mountain herbage, that crowned the brow of a precipice. …

8As he was about to descend, he heard a voice from a distance, hallooing, “Rip Van Winkle! Rip Van Winkle!” He looked round, but could see nothing but a crow winging its solitary flight across the mountain. He thought his fancy must have deceived him, and turned again to descend, when he heard the same cry ring through the still evening air; “Rip Van Winkle! Rip Van Winkle!” — at the same time Wolf bristled up his back, and giving a low growl, skulked to his master’s side, looking fearfully down into the glen. Rip now felt a vague apprehension stealing over him; he looked anxiously in the same direction, and perceived a strange figure slowly toiling up the rocks, and bending under the weight of something he carried on his back. …

(The stranger was dressed after the antique Dutch fashion and was carrying a large barrel of liquor. With Rip’s help and without speaking they got to a hollow where they saw a company of similar looking men. Though they were playing ninepins, they kept grave silence. Rip having approached nearer, they eyed him fixedly and suspiciously. Obeying his companion’s signs, Rip helped serve the drink, took a few draughts, and fell into a deep sleep.

Waking on a bright sunny morning, he found no men or liquor, or dog, either; and his gun, he thought, had been replaced by an old rusty one. Hungry, with a heavy heart, anticipating an outburst of fierce rage from his wife, he trudged homeward.)

9As he approached the village he met a number of people, but none whom he knew, which somewhat surprised him, for he had thought himself acquainted with every one in the country round. Their dress, too, was of a different fashion from that to which he was accustomed. They all stared at him with equal marks of surprise, and whenever they cast their eyes upon him, invariably stroked their chins. The constant recurrence of this gesture induced Rip, involuntarily, to do the same, when, to his astonishment, he found his beard had grown a foot long! …

10He entered the house, which, to tell the truth, Dame Van Winkle had always kept in neat order. It. was empty, forlorn, and apparently abandoned. This desolateness overcame all his connubial feats — he called loudly for his wife and children — the lonely chambers rang for a moment with his voice, and then all again was silence.

11He now hurried forth, and hastened to his old resort, the village inn — but it too was gone. A large rickety wooden building stood in its place, with great gaping windows, some of them broken and mended with old hats and petticoats, and over the door was painted, “The Union Hotel, by Jonathan Doolittle.” Instead of the great tree that used to shelter the quiet little Dutch

40

inn of yore, there now was reared a tall naked pole, with something on the top that looked like a red night-cap, and from it was fluttering a flag, on which was a singular assemblage of stars and stripes — all this was strange and incomprehensible. He recognized on the sign, however, the ruby face of King George, under which he had smoked so many a peaceful pipe; but even this was singularly metamorphosed. The red coat was changed for one of blue and buff, a sword was held in the hand instead of a sceptre, the head was decorated with a cocked hat, and underneath was painted in large characters, GENERAL WASHINGTON.

12There was, as usual, a crowd of folk about the door, but none that Rip recollected. The very character of the people seemed changed. There was a busy, bustling, disputatious tone about it, instead of the accustomed phlegm and drowsy tranquillity. He looked in vain for the sage Nicholas Vedder, with his broad face, double chin, and fair long pipe, uttering clouds of tobacco-smoke instead of idle speeches; or Van Bummel, the schoolmaster doling forth the contents of an ancient newspaper. In place of these, a lean, bilious-looking fellow, with his pockets full of handbills, was haranguing vehemently about rights of citizens — elections — members of congress — liberty — Bunker’s Hill — heroes of seventy-six — and other words, which were a perfect Babylonish jargon to the bewildered Van Winkle. …

13…At this critical moment a fresh comely woman pressed through the throng to get a peep at the gray-bearded man. She had a chubby child in her arms, which, frightened at his looks, began to cry. “Hush, Rip,” cried she, “hush, you little fool; the old man won’t hurt you.” The name of the child, the air of the mother, the tone of her voice, all awakened a train of recollections in his mind. “What is your name, my good woman?” asked he.

“Judith Gardenier.”

“And your father’s name?”

“Ah, poor man, Rip Van Winkle was his name, but it’s twenty years since he went away from home with his gun, and never has been heard of since — his dog came home without him; but whether he shot himself, or was carried away by the Indians, nobody can tell. I was then but a little girl.”

Rip had but one question more to ask; but he put it with a faltering voice: “Where’s your mother?”

“Oh, she too had died but a short time since; she broke a blood-vessel in a fit of passion at a New-England peddler.”

There was a drop of comfort, at least, in this intelligence. The honest man could contain himself no longer. He caught his daughter and her child in his arms. “I’m your father!” cried he — “Young Rip Van Winkle once — old Rip Van Winkle now! — Does nobody know poor Rip Van Winkle?”...

14He used to tell his story to every stranger that arrived at Mr. Doolittle’s hotel. He was observed, at first, to vary on some points every time he told it, which was, doubtless, owing to his having so recently awaked. It at last settled down precisely to the tale I have related, and not a man, woman, or child in the neighborhood, but knew it by heart. … The old Dutch inhabitants, however, almost universally gave it full credit. Even to this day they never hear a thunderstorm of a summer afternoon about the Kaatskill, but they say Hendrick Hudson and his crew are at their game of nine pins; and it is a common wish of all henpecked husbands in the neighborhood, when life hangs heavy on their hands, that they might have a quieting draught out of Rip Van Winkle’s flagon…

UNIT

3

ROMANTICISM AND THE AMERICAN RENAISSANCE 1820 – 1865

41