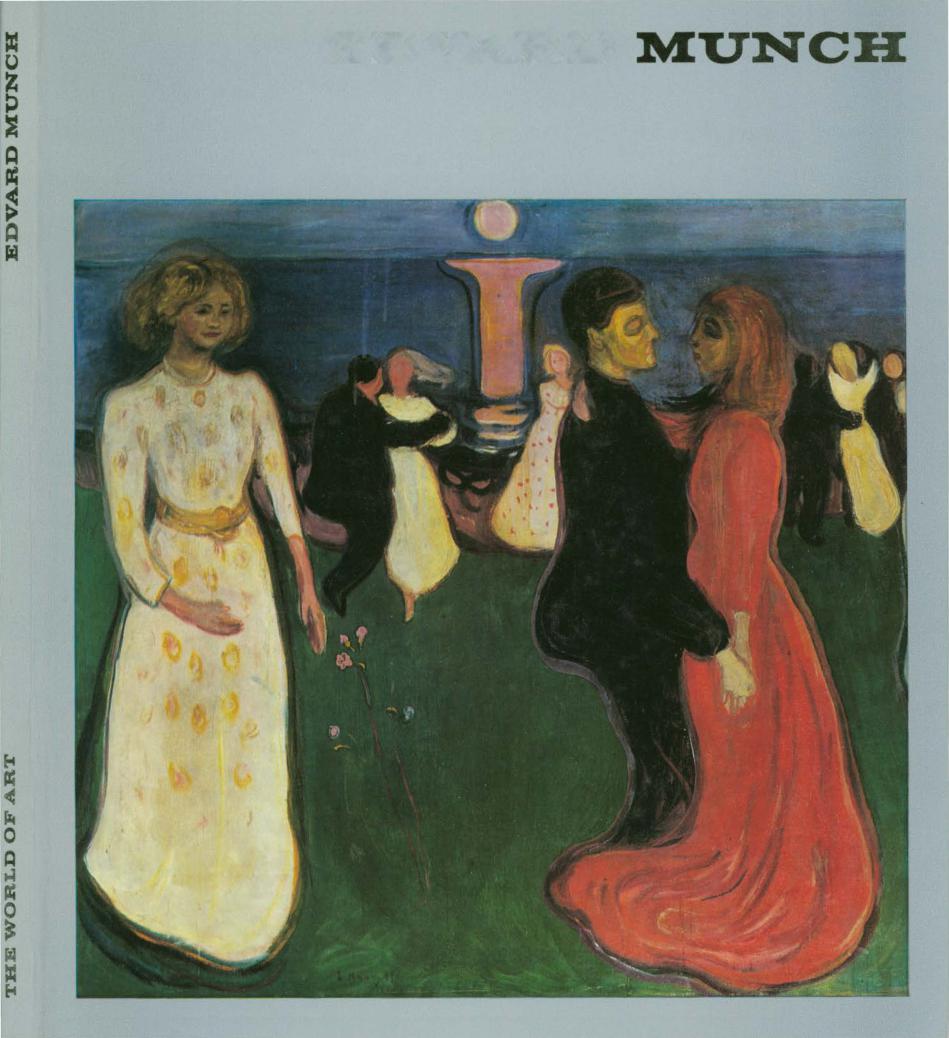

Werner Timm - Edvard Munch - 1982

.pdf

EDVARD

MU

N

CH

TheWorld of Art |

WernerTimm |

|

Edvard Munch |

|

With eighteen Plates in colour |

|

and forty-five monochrome Illustrations |

|

Henschelverlag |

|

Kunst und Gesellschaft ·Berlin 1982 |

Translated by Lisbeth Gombrich

©1 973 Henschelverlag Kunst und Gesellschaft, DOR - Berlin (Original)

©1 9 8 2 Henschelverlag Kunst und Gesellschaft, DOR - Berlin (English translation)

The Norwegian painter Edvard Munch ranks among the pioneers of Modern Art alongside Cezanne, Gauguin, Hodler and Toulouse Lautrec. Though while they lived these artists were largely un recognized and misunderstood they are seen today as "the Classics" of the Modern Movement and their works are viewed with admira tion, indeed with reverence. Many of the major developments of later decades, that is to say, especially some of the radical features associated with the rise of the Expressionist movement, can be traced back to the late nineteenth century. Two of the masters j ust mentioned excelled in the graphic arts: Toulouse-Lautrec and Munch. It is probably not without significance that both became interested in this medium more or less at the same time, in the years between 1 89 1 and 1 894. Munch's graphic ceuvre probably exceeds in importance his work as a painter.

One of Gauguin's paintings from the South Seas bears the title: "Where do we come from? What are we? Where are we going?" One would not have expected such strange existential doubts in the dream world .Gauguin thought he had found in the South Pacific island paradise he strove to depict in his paintings. No doubt he had carried these questions with him from a Europe which he had left frustrated and disgusted. Munch's attitude was different. The young man -was irresistibly drawn to the focal points of Europe's intellectual and cultural life. Oslo, Paris and Berlin were the major stations of his pilgrimage there to dp battle with the same inescapable questions. Indeed his entire life must be seen as a con frontation with those haunting problems of human existence which dominated the consciousness of the Western World around the turn of the century. He was driven by an urge to analyse in depth the situation of man as it presented itself to him in these exciting con troversial days, to depict Life with its despair and its exultations as he himself experienced it. In 1 8 8 8/89 he conceived the plan to create a comprehensive sequence of paintings to be called "The Frieze of Life": "I think of the 'Frieze of Life' as of a series of pictures held together by one unified theme: between them they are to present a picture of Life in all its variety, with all its joys and sorrows ."

The most cursory look at this work reveals that what he had in mind was anything but a series of genre pictures showing the different stages of human life. As he himself expressed it at a later occa sion, he conceived his work as a "reaction against the realism which became more and more en vogue at his time."

His famous dictum that a picture should not show '"a woman, knitt ing', or 'a man, reading', but human beings, people who are alive, who breathe and feel, who love and suffer" was indeed the formu lation of a programme. What he objects to is not so much the subject matter as such but the escapist attempt which avoids tackling vital problems of existence by concentrating on an idyllic naturalism.

Stanislaw Przybyszewski, a Polish-born German poet who became a close friend of the painter's in Berlin, describes Munch's aims more precisely: "Edvard Munch is the first artist who has undertaken to depict the most complex and most subtle happenings in the human soul." Whenever Munch depicts important events in human life he invariably seeks to make visible the emotional experience behind them. This is why he, along with Van Gogh, exercised a decisive influence on the development of Expressionism: for him, the repre sentation of emotional experience had precedence over the repre sentation of visual experience. Indeed, painting human emotions was for him what painting was about. This aim could clearly not be achieved with the traditional means of the Norwegian school he had started from for this had strong naturalist leanings. He had to find new ways. He sought to achieve his aim by a radical simplifica tion of forms, a renunciation of all unnecessary detail, a pronounced intensification of colour, and a severe concentration on the main subject. Thus he developed tendencies not unlike those one can discern in Gauguin, Van Gogh, Toulouse-Lautrec and Hodler.

The effect his new themes and his new means of expression made on the public, and indeed on many fellow artists, is perhaps best illustrated by the famous scandal which erupted at Munch's exhibi tion in Berlin in the year 1 89 2 . The dismay and uproar unleashed by his canvases was such that his opponents in the Society of Berlin Artists succeeded, if only by a small majority, to force the closure of the exhibition a few days after it had opened-notwithstanding the fact it was their society which had invited Munch in the first place. However the repercussions of the scandal set things moving in Berlin's artistic circles. A group of progressive artists protested against the decision, the "Moderns" asserted themselves and the Society of Berlin Artists split. In 1 899 the "Secession," in which the Impressionists were the dominating group, was formed under Lie bermann and Leistikow. It should probably be pointed out at this juncture that Munch's ideas were considerably ahead of those of the "Secession" and more in tune with those of the "New Secession"

5

great importance for him personally is characteristic for his mode of working. Many of his paintings exist in numerous versions and variants witnessing to his unceasing intense preoccupation with their subject matter. The first version of "The Sick Child" was started

in 1 8 8 5 ; the last one was painted in 1 9 2 5 |

. In |

addition |

he made |

several graphic versions. For ever since he |

had |

started |

etching in |

1 894 and had become interested in the graphic media, painted and graphic versions of the same subject tend to exist side by side, pre senting ever new solutions in two independent chains of pictorial representation. Munch was perhaps even more a pioneer in the graphic media than in painting. He was a master of etching ; he derives unexpectedly sensitive and expressive effects from the porous strokes of chalk lithography, notably in his Paris colour lith ograph of "The Sick Child" which is perhaps his masterpiece in that medium. Though Gauguin had made some tentative experi ments with the technique, it was Munch who created an entirely new type of wood-cut in which large areas are contrasted, the traces of the burin are allowed to remain and even the figure of the wood is used to produce powerful graphic effects. His work anticipates the expressive style of wood-cutting associated with the German group "Die Brucke" (The Bridge) , with names like Kirchner, Schmidt-Rottluff, Heckel and Nolde.

The personal experience underlying the picture of the sick child is the early death from consumption of Munch's eldest sister Sophie who survived their mother by only a few short years. These tragic events did not only darken his childhood and youth-they deeply affected his entire life. When Munch paints death, it is not a pale allegory but the vivid reflection of a painfully real experience. We sense it in the peculiar oppressive atmosphere of his death-chamber scenes and in the intensely moving ebbing away of the sick child's life. It would be wrong to talk here of motifs or subjects in the con ventional sense. These are bitter experiences weighing heavily on the artist's soul and clamouring to be given shape. Their artistic ex pression has probably helped him to a certain extent to come to terms with his obsessive memories.

The history of Munch's famous picture "The Scream" illustrates well the-strong effect events in nature could have on him. We know from words written on an early study that it is based on one particular personal experience : an evening stroll with two friends in the sett ing sun. Suddenly he is vehemently seized by the haunting mood

Woodland path. 20 x 26. 5 cm. Coloured chalk. After 1 9 1 0. Oslo, Munch Museum

of the sombre fjord landscape overarched by a blood-red sky. In his artistic response the static landscape becomes wildly dynamic, filled with menacing sinuous lines-a sombre northern counterpart to Van Gogh's passionately flaming landscapes. The violent vibra tions take hold of the figure in the foreground so that it squirms and twists under the impact and breaks into a scream. "By painting those colours and lines and forms which I had seen in a mood of violent emotion I want to re-create that emotional experience exactly as a phonograph reproduces sound." This is how Munch himself ex plained his attempts to give visible expression to the inner life of the emotions. Many travellers to northern latitudes have told of the strong psychological effect of atmospheric phenomena. "Sometimes the air itself seems to be a rusty red or a sulphuric yellow-the Twilight of the Gods I" we read in Karl Hofer's vivid record of a journey to Norway. Such must have been Munch's personal ex perience-in an early version we see a man standing by the railing who is clearly no other than the artist himself. However, what Munch distilled from this intense subjective experience was something that far transcended that significance. Panic fear as such, the inescapable fear of all living things, and more specifically "Weltangst"-that global existential fear which pervaded that epoch of a declining

7

bourgeois society-was made manifest with frightening clarity as in an apocalyptic vision.

In 1 8 84 Munch became a member of a radical group in the Norwe gian capital, led by Hans Jager. The group which called itself the Christiania Boheme was the focus of passionate discussions on all things political, social, literary and philosophical such as the writ ings of Nietzsche and Darwin, the role of women in society, the ethics of "free love" and the whole complex of the relationship of the sexes where the old solutions had suddenly become problemati cal. Similar topics, such as man's isolation and alienation in the so cial conditions of the times, the frustration of vital natural urges by a moral code that had lost its meaning, the protest against stifling con vention and the dramatic conflicts arising from rebellion against it were moreover the main subject matter of the avantgarde literature of the day in which the Scandinavians played a major role. Henrik Ibsen, August Strindberg, Alexander Kielland, Jonas Lie and Arne Garborg are concerned with the same social problems Munch grap pled with in his work-a fact borne out by the strong parallels one can discern between the symbolic figures in his paintings and those in some of Ibsen's plays. The dramatists among which Ibsen was of course the most important formulated these problems in a convincing and affecting way. But Munch's art went further. Behind the prob lems posed by the social conditions of the day he shows us the time less grandeur of Eros in pictures of unbounded passion. The true meaning of love's awakening, of longing, loneliness, jealousy and separation is expressed in works of an intensity and artistic mas tery unsurpassed to this day.

The p rint entitled "Disengagement"-steeped as it is in the deep blue colour of longing-makes us feel the force and power of erotic love even in the hour of parting. The sensitive empathy manifest in such scenes makes us realize that the era of psychoanalysis was about to begin.

Munch's "Frieze of Life" shows comparatively few happy lovers . "Conception," "The Kiss," and "To the Woods" show these rare moments of fulfilment. A familiar motif of old German art, that of Death and the Maiden, is also taken up by Munch. In fact much of his work could be subsumed under the general title of "Eros and Death." Munch saw in them the inexorable powers that rule our lives. One of his early pictures shows a voluptuous young woman in Death's passionate embrace, a symbol of Life's rise and fall.

Munch's thoughts were greatly occupied with the relationship of the sexes. Not only with the then burning question of woman's place in society but even more so with the problems created by his own personal encounters with women. Many of his pictures reflect with varying degrees of transformation his own highly ambivalent sub jective experiences : the dualism of desire and fear, of love and de monic terror. His attitude to women was rather similar to that of Strindberg whom he had met in Berlin and Paris. In one of his poems Heine describes woman as a vampire suckingthe blood of men . Munch does the same. He paints Salome who demands the head of the man who spurns her love, and "The Death of Marat," seen as the triumph of woman over man. Yet at the same time, and even more so after the great nervous crisis of 1 908 he painted superb portraits of women which prove his love and respect for womanhood. Indeed, few artists have had a more sensitive understanding of the female psyche. Varying the title of a famous exhibition of Munch's pictures one might speak in connection with his art of "pictures from the inner life of women. " Pictures like "The Voice" (showing a young girl in a state of vague expectation and longing in a summer landscape) , "Puberty," or "Madonna" (showing ecstatic surrender in the face of a woman at the moment of conception) may be cited as examples. Another of his pictures, which he called "Sphinx" or "The Three Faces of Woman," shows three symbolic female figures : a young girl in a light-coloured dress, looking longingly out to sea, a mature woman, naked , "dominated by sexual desire," and a third one in dark attire, nun-like,'melancholic and contemplative. The centuries old theme of the stages of life is here re-interpreted psychologically in a highly differentiated form, yet without undue analytical dissection. What we have here in front of us is a taut and forceful statement of the basic situation : not so much an allegory as a drama of destiny.

Though Munch is in the first place a painter of human figures his landscape paintings are an important part of his reuvre. For him all existence is rooted in landscape. It is the background against which human destiny unfolds . With a symbolism heightened by the Nordic tendency towards the supernatural he regards earth, sea and forest as tremendous symbolic forces which yet are imbued with real power. The reflection of light from the midnight sun or the full moon ap pearing like a glittering column on the water to the people on the shore is turned by him into a phallic symbol signifying the cosmic

8

union of heaven and earth, as Theodor Diiubler has shown in a beautiful, remarkably perceptive essay on Munch's thoughts and feelings.

Munch often painted the white midsummer nights when after the sheer endless depressing darkness of the Nordic winter life is felt to pulsate with redoubled vigour. There is little doubt that Norway's climate and landscape, with its limitless expanses of sea and the austere beauty of its fjords, together with the characteristic trend of the Nord ic people towards a brooding melancholy and a sense of

Lovers in bed . 26 . 5x 20 cm. Indian ink and water-colour over pencil drawing. Ca. 1 92 5. Oslo, Munch Museum

the supernatural have exerted an important influence on Munch's art. It was clearly their metaphorical significance he had in mind when he spoke of the "White nights of midsummer in which life and death, day and night go hand in hand ."

In his "Frieze of Life" pictures the backgrounds are always coastal landscapes . These are not merely meant to represent a uniform back drop but are a symbolic expression of the contrast between the eter nal immutability of nature and the shortness of our human lives. Many of his paintings represent the shore of Asgardstrand on Oslo fjord where Munch spent most of his summers and renewed his strength by communing with the simple grandeur of the environ ment.

In Munch's early works landscape does not exist in its own right. It is used to underline the mental state of the persons in the picture; Munch projects their emotions into it and makes it an expression of a general mood. It is amazing to see how marvellously he can express psychological states by the curving line of a sea shore, the grouping of trees, and similar devices.

In 1 908 Munch suffered a severe nervous breakdown . The preceding twenty years with their constant unrest and their many conflicts had undermined his constitution and necessitated a prolonged sojourn in a nursing home. He recovered, but the experience meant a change in his way of life. Even before the crisis he had often talked about returning "one day" to Norway "where nature is commensurate with my art." Now he forsook the hectic life of the cities, sought the rural solitude of his native land and settled down. As the shadows that had oppressed him became lighter (they never completely dis appeared) his attitude to his environment changed , and naturally this change had a strong effect on his landscape painting. Nature now revealed to him her own inherent beauty. We owe to this period a number of works of an almost serene, mature calm depict ing the monumental fjord scenery around him in all its majesty. He saw with new eyes.

Munch's great sensitivity for psychological nuances made him a nat ural portrait painter. We possess a great many of such works in vari ous techniques and media-comprising brilliant portrait sketches, carefully executed heads and life-size full-length portraits of his sit ters . His portrait of Hans Jager has already been mentioned ; the life-size picture of Walther Rathenau provides a splendid example of his more formal manner. A perfect sense of style enables him to

9

combine a monumental format with psychological insight into the character of the person portrayed. Posture, gesture and physiognomy interact to express his personality. His portraits of children have a peculiar charm. Though he was reputedly not at ease in their com pany-possibly because of a feeling of awkwardness and self-con sciousness-their untamed pristine innocence must have touched him deeply or he would never have been able to paint children as he did .

Munch has left us a great many self-portraits. Certainly not out of vanity, but rather from a desire to meet himself face-to-face, to conduct a dialogue with himself. It seems significant that artists of a serious reflecting cast of mind tend to paint their own features particularly often. One thinks of Durer, Rembrandt, Van Gogh , Corinth , and Kathe Kollwitz. Munch's selfportrait of 1 895 (the

A sense of fear. 3 7 . 4 x 3 2 . 3 cm. Ind ian ink and oil over pencil sketch. 1 896. Oslo, Munch Museum

first in a graphic medium) shows us the artist at the age of thirty-one during his stay in Paris. The face appeares to float before a dark mysterious background ; at the bottom edge there is a sceleton arm a silent Like the late self-portrait "Between Clock and Bed" this lithograph is over-shadowed by thoughts of illness and death.

Isolated instances of pictures showing men at work can be found in Munch's work from about 1 900 onwards. But not until after 1 90 8 , when h e had retired to the country and was i n frequent contact with labourers , farmers, fishermen, building workers and mechanics, did he take a serious interest in the subject. By watching them at their work and observing their simple yet meaningful activities unselfcon sciously carried out he gained a new, more positive view of the-in dividual's position in society. Remarks he made about the working class indicate that he saw in it a new social force destined one day to take the place of the bourgeoisie. A letter addressed to Dr. Rag nar Hoppe in February 1929 indicates that he thought deeply about the need to change the role of art in society : "I am aware that there has lately been considerable opposition in the Scandinavian coun tries to my way of painting, my large formats and my attempts to lay bare the innermost workings of the human soul. The 'Neue Sachlichkeit' movement (the new realism) with its stress on detail. its flat brushwork and its small sizes is everywhere in the ascen dancy. But I believe that this movement will soon give way to a new spirit. For the small pictures with their wide frames are primarily designed for the living room. They represent bourgeois art, or rather, that art dealer's art that rose to prominence after the victory of the bourgeoisie in the French Revolution. Now it is the time of the workers. Soon art will be the property of everybody and will have its place on the large walls of our public buildings ."

It is easy to see that when Munch paints men at work, be they road builders, ploughmen, labourers shovelling snow or just any worker in full figure, he eschews all false over-emphasis but seeks to impart to his subjects a noble simplicity and dignity. Hodler had gone further. His wood-feller is more stylized , more exaggerated in his movements, more highly charged and emphatic. Munch deviat s less from reality. He obtains greatness and significance merely by simplification and a restrained use of heightened forms.

New tasks arose for Munch in the years 1 909 to 1 9 1 1 out of his participation in the competition for the job of adorning the walls of

10