Wiberg M. - The Interaction Society[c] Practice, Theories and Supportive Technologies (2005)(en)

.pdf192 Kakihara, Sørensen & Wiberg

tion Systems Research Seminar in Scandinavia (IRIS 23). Laboratorium for Interaction Technology, Trollhättan Uddevalla University, Sweden.

Norman, D.A. (1993). Things that make us smart. Defending human attributes in the age of the machine. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley.

O’Conaill, B., & Frohlich, D. (1995). Timespace in the workplace: Dealing with interruptions. In Proceedings of CHI’95 Human Factors in Computing Systems, New York (pp. 262-263). ACM Press.

Olson, G.M., & Olson, J.S. (2000). Distance matters. Human-Computer Interaction, 15, 139-178.

Rouncefield, M., Viller, S., Hughes, J., & Rodden, T. (1995). Working with constant interruption: CSCW and the small office. The Information Society, 11 (4), 173-188.

Schmidt, K., & Simone, C. (1996). Coordination mechanisms: An approach to CSCW systems design. Computer Supported Cooperative Work: An International Journal, 5 (2&3), 155-200.

Schön, D.A. (1983). The reflective practitioner: How professionals think in action. New York: Basic Books.

Schultze, U., & Vandenbosch, B. (1998). Information overload in a groupware environment: Now you see it, now you don’t. Journal of Organizational Computing and Electronic Commerce, 8 (2), 127-148.

Sørensen, C., Fagrell, H., & Ljungstrand, P. (2000). Traces: From order to chaos. In K. Braa, C. Sørensen, & B. Dahlbom (eds.), Planet Internet (pp. 113-136). Lund, Sweden: Studentlitteratur.

Suchman, L.A. (1987). Plans and situated actions: The problem of humanmachine communication. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Tang, J.C., Yankelovich, N., Begole, J.B., Van Kleek, M., Li, F., & Bhalodia, J. (2001). ConNexus to Awarenex: Extending awareness to mobile users. CHI 2001, 3 (1), 221-228.

Urry, J. (2000). Sociology beyond societies: Mobilities for the TwentyFirst Century. London: Routledge.

Weilenmann, A. (2001). “I can’t talk now, I’m in a fitting room:” An initial investigation of the ways in which location features in mobile phone conversations. In Proceedings of the Workshop on “Mobilize!: Interventions in the Social, Cultural and Interactional Analysis of Mobility, Ubiquity and Information and Communication Technology.”

UK: Digital World Research Centre, University of Surrey.

Copyright © 2005, Idea Group Inc. Copying or distributing in print or electronic forms without written permission of Idea Group Inc. is prohibited.

Fluid Interaction in Mobile Work Practices 193

Whittaker, S., Davies, R., Hirschberg, J., & Muller, U. (2000). Jotmail: A voicemail interface that enables you to see what was said. InProceedings of CHI2000 Conference on Human Computer Interaction (pp. 8996).

Whittaker, S., Swanson, J., Kucan, J., & Sidner, C. (1997). TeleNotes: Managing lightweight interactions in the desktop. Transactions on Computer Human Interaction, 4, 137-168.

Wiberg, M. (2001). In between mobile meetings: Exploring seamless ongoing interaction support for mobile CSCW. PhD Dissertation. Umeå University, Sweden.

Wiberg, M. (2002). Interaction, interruptions, and lightweight support for availability management: A pre-study of issues related to the fluidity of work in the interaction society. Working paper 02.03, Department of Informatics, Umeå University, Sweden.

Wiberg, M., & Ljungberg, F. (2001). Exploring the vision of “anytime, anywhere” in the context of mobile work. In Y. Malhotra (ed.), Knowledge Management and Virtual Organizations (pp. 157-69). Hershey, PA: Idea Group Publishing.

Wiberg, M. & Whittaker, S. (2004). Managing interruptions: Supporting lightweight availability negotiations on mobile phones. Submitted to internationaljournal.

Endnote

*The authors have all contributed equally to this chapter and are listed in alphabetical order only.

Copyright © 2005, Idea Group Inc. Copying or distributing in print or electronic forms without written permission of Idea Group Inc. is prohibited.

194 Holmström

Chapter VIII

Mobile IT as Immutable

Mobiles?

Exploring the Enabling

Qualities of a

Mobile IT Application

Jonny Holmström

Umeå University, Sweden

Abstract

This chapter explores the social consequences of mobile IT. Even though the need for better theorizing on the topic has been highlighted recently, most attempts to date have failed not only to properly explore the social consequences of mobile IT, but also in being specific about the technology itself in any detail. A promising approach with which to explore mobile IT and its social consequences may be found in actor network theory (ANT). ANT’s rich methodology embraces scientific realism in its central concept of hybrids that are simultaneously technological and social. The advantages of conceiving mobile IT applications immersed in and a part of a network of hybrids are explored by drawing from a project concerned with mobile IT use in the context of the mobile bank terminal (MBT). It was found that the users were less than enthusiastic over the MBT, and two key problems

Copyright © 2005, Idea Group Inc. Copying or distributing in print or electronic forms without written permission of Idea Group Inc. is prohibited.

Mobile IT as Immutable Mobiles? 195

were identified. First, the poor design of MBT hampered the possibilities for ad-hoc activities. Second, the users felt that ad-hoc activities could be seen as somewhat irresponsible in the context of banking business. To this end, the problems related to the MBT use were both social and technical. We conclude by identifying and elaborating on some aspects of the social consequences of mobile IT use in order to shed new light on the possibilities and challenges that mobile IT use conveys.

Introduction

Dramatic advances in technology, fierce economic competition, and processes of globalization are changing the world at a rapid pace. Linked to these changes is the need for increased and ongoing interconnectedness between people. Most pertinent, perhaps, of today’s advanced technologies are the new and highlyadvancedmobileITapplications.Clearly,interestinmobileapplications is increasing, and savvy firms are pondering the strategic implications of m- commerce to their products and markets. Mobile phones are becoming omnipresent and we are only beginning to see their effects on social and economic life. Worldwide, at the beginning of 2000, the number of cellular subscriptions was 470 million, and this was thought to grow to 1 billion by the end of 2003 (Ovum, 2000). It is also thought that the number of Internetenabled mobile phones (using WAP or its successors) will increase from 1.1 million at the end of 1999 up to somewhere around 80 million worldwide by 2003 (Jupiter Communications, 2000; Yankee Group, 2000).

A central question for IT researchers is how the process of mobile IT use changesperceptionsofrelationshipsandinterpretationsoftimeandspace.This paper seeks to answer this question and provide a direction for future research on mobile IT use. To this end, it is important to consider technological as well as social issues in this process.

It is fair to say that, in general, research on mobile IT use has not often been theory-informed. More typically, research on mobile IT use has been primarily an observational endeavor composed of a diverse and idiosyncratic range of studies, often uncoupled to each other and to theory. This lack of theoretical platform is unfortunate, as researchers are confronted with a great number of different technologies and a great diversity of contexts. Although it can be argued that recent research on mobile IT use has been better linked to theory

Copyright © 2005, Idea Group Inc. Copying or distributing in print or electronic forms without written permission of Idea Group Inc. is prohibited.

196 Holmström

(e.g., Cooper, 2002; Kopomaa, 2000; Laurier, 2002), a clear need remains in research on mobile IT use to improve the linkage between formal theory and observations.Anancillaryneedisforthefieldtodevelopcentral,keyquestions that are pertinent today, but unanswered.

For this reason, the present study undertakes a further analysis to understand the dynamics of mobile IT use. The study is an attempt to explore issues of temporality and spatiality, and their relation to mobile IT. The study examines empirically experiences from a project focused on the development of a mobile IT application to be used by bank customers. The findings highlight the theoretical implications of the combined deployment of notions of time and space in the use of mobile IT, and contribute to the literature on IT-enabled activitiesinabroadersense.Finally,theresultsyieldpracticalinsightsintohow we can best support mobile IT use.

Understanding Mobility

Mobile IT and the Need for Better Theorizing

The topic of mobile IT use brings together, ideally, theories about the organization of social behavior, and the enabling role that technology plays in such processes. Mobile IT use, thus, should be seen as an emergent property, resulting from technological advances and social organization.

Dahlbom & Ljungberg (1999) discuss the need for better theorizing on the topic:

“Once IT support for mobile work is brought into focus as an important subject matter of informatics, our discipline receives a whole new agenda. Mobile IT use, mobile computing becomes the subject matter of what we may call mobile informatics, and in view of the importance of its subject matter, mobile informatics becomes one of the more important sub-disciplines of our discipline. We need to develop a theory of mobile IT use. And in order to do so we have to answer such questions as: Why has mobility increased? What are the major varieties of mobile IT use? How do we define mobile computing (mobile IT use)? What are the condi-

Copyright © 2005, Idea Group Inc. Copying or distributing in print or electronic forms without written permission of Idea Group Inc. is prohibited.

Mobile IT as Immutable Mobiles? 197

tions of mobile work and other activities that now become mobile? What kind of technology is there to support mobile activities, and what kind of technology could we develop?” (Dahlbom & Ljungberg, 1999, pp. 228-229)

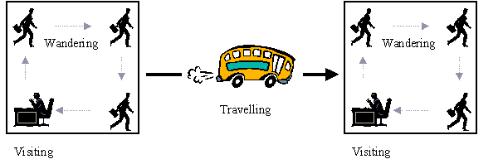

As an attempt to explore the issue theoretically, Kristoffersen & Ljungberg (1998) attempt to name and frame mobility in three aspects or modes:

•Traveling – refers to the movement towards a specific goal. This is an activity that takes place when traveling in a vehicle. From the perspective of mobile IT support, we find technologies such as street finders and restaurant guides, etc. However, this modality can allow for stationary IT use as well.

•Visiting – refers to the ways in which a person stays in a specific place before moving on to other places. It is an activity that happens in one place and for a restricted period of time.

•Wandering – refers to movement within a limited area or domain. For instance, the IT support staff described by Kristoffersen & Ljungberg (1998) spend much of their time “wandering” around the building to meet users that want their help. This extensive local mobility is referred to as wandering.

Unfortunately, these aspects of mobility does very little to uncover the very character of mobility. First, it says little or nothing of the ways in which mobile ITenabledthesemodalities.Second,implicitinthesemodalitiesisthattheyare

Figure 1. Three modalities of mobile IT use

Copyright © 2005, Idea Group Inc. Copying or distributing in print or electronic forms without written permission of Idea Group Inc. is prohibited.

198 Holmström

temporary and can only be understood from the point of view of that which is to be considered as “normal” is not mobile. In other words, they all relate to a “home base” (Wiberg, 2001: 72) that is not mobile in its character.

It is important that we explore mobile IT use in more detail. Mobile ITs are everywhere and their implications cannot be grasped by looking at mobile IT use as merely a temporary deviation for that which is stable, stationary, and static.Recognizingthepervasivenessoftoday’smobileITapplication,Lyytinen & Yoo (2001) describes “nomadic computing” as something of paradigmatic importance in that it changes not only our society in a profound way but also requires us to reconsider some of the fundamental and underlying assumptions in IS research. Being nomadic, in their view, is not a temporary mode we pass through between stationary modes, but rather something we constantly face and thus something in need of critical scrutiny.

A nomadic information environment, in Lyytinen & Yoo’s (2001) view, is described as:

“…a heterogeneous assemblage of interconnected technical and organizational elements, which enables physical and social mobility of computing and communication services between organizational actors both within and across organizational borders. The novel features of such an environment are its high level mobility, the consequent large scale of services and infrastructure, and the multiplicity of services in terms of data processes and transmitted

– often called digital convergence. These three technological drivers – mobility, digital convergence, and mass scale – underlie most developments in future computing technology” (Lyytinen & Yoo, 2001, p. 3).

Recognizing the fundamental shift for IT use that the mobile IT applications represent is an important endeavor, and downplaying this by explicitly or implicitly understanding mobility as a temporary state and to understand the stationary and static as the default, would be to miss a central and paradigmatic societal shift. Thus, we recognize that the model presented by Kristoffersen & Ljungberg (1998) provides us with a somewhat limited understanding of mobility. For the purposes of this paper, we will seek to explore the character of mobility from a theory-informed perspective, so as to better understand not only the social interplay of multiple actors who attempt to make sense of their

Copyright © 2005, Idea Group Inc. Copying or distributing in print or electronic forms without written permission of Idea Group Inc. is prohibited.

Mobile IT as Immutable Mobiles? 201

is for one actor to get another actor (or network of actors) to act in a desired manner. The changes that occur are referred to as translation.

Another important concept is that of immutable mobiles. We are faced with immutable mobiles when objects “have the properties of being mobile but also immutable, presentable, readable and combinable with one another” (Latour, 1990, p. 26). Immutable mobiles thus provide us with a way of “structuring vision” where we probably find the map as the best example. It is “immutable” in as much as it remains the same as it passes through time and space, and “mobile” to the degree that it can be circulated from hand to hand. Constructing an immutable mobile demands that all the inscriptions to be placed within it be first produced and then collected in one particular place — a “centre of calculation.”However,itshouldbenotedthatimmutablemobilesrequiresome work function. In short, they still need to be immersed in a network (Mol & Law, 1994).

The theoretical framework for studying mobile IT applications must be sufficiently rich to comprehend the complexities of these the interactions involved, and ANT offers a promising set of analytical resources for this purpose [see Cooper (2002) for an example of ANT used to explore the nature of mobile IT].

The Case of MBT – An Offline Service for Mobile Banking

To illustrate the interplay between technology and social practices in the context of mobile IT use and to provide a concrete example of how this new technology enables support for new activities across time and space we will below outline a case study of MBT — a Mobile Bank Terminal.

Background and Research Methodology

The Swedish bank Föreningssparbanken has developed a mobile bank terminal (MBT) as an additional customer channel to their infrastructure (besides ATMs, the telephone bank, the WAP bank, and the Internet bank). For the purposes of the first version of MBT the bank made use of a Compaq handled computer, an iPAQ 3630 together with a GSM-phone with possibili-

Copyright © 2005, Idea Group Inc. Copying or distributing in print or electronic forms without written permission of Idea Group Inc. is prohibited.

202 Holmström

ties for communication via Bluetooth or IR. It allows the user to do all various kinds of activities that can be done today on the Internet bank or the telephone bank (e.g., checking account balance, move certain amount of money between different accounts, pay bills, etc.).

The target group for this service is well-educated business people looking for time-efficient technologies to enable them to do things like banking while waiting for something else (e.g., while sitting on a train waiting to reach the destination). This target group was chosen based on an assumption that these persons are probably interested in new technology, are typically used to technology in their work life, and probably have a relatively high income. Anotherassumptionmadewasthatitisimportanttohavecomfortablesolutions anddifferentchannelsformanagingbankbusinessfortoday’sbankcustomers.

The MBT banking service is implemented on handheld devices and has been co-developed by Föreningssparbanken and a company in the US. The MBT is still a research prototype but has been put into use in a pilot study. The study involved 100 test persons. This relatively large test group consisted of people working in the bank as well external persons. During a period of three months the MBT prototype was tested by people working at the bank and external persons. During the test period the test persons borrowed the handheld devices from the bank with the MBT application preinstalled. As a precondition for becoming a test person the person needed to be: 1) a customer at the bank, and 2) an Internet bank customer at the bank, to be able to pay their bills via the Internet bank. The only instruction given to the test persons was to feel free to use the MBT as much as they liked, but at least three times every week. They also committed themselves to fill out a questionnaire handed out by the bank in the end of the test period.

The empirical material was collected through 11 semi-structured interviews with MBT users, and two interviews with the project manager. These interviews were conducted at the bank’s head office in Stockholm on two occasions. During the first occasion the project manager and three users were interviewed. During the second occasion the project manager was interviewed again, and an additional eight users were interviewed. These interviews were all audio taped and transcribed. In addition, four different meetings were held with people involved with the project where we got information and documentation about the project, gained access to the users, and were presented with the MBT application. In the presentation of the results the users are given numbers from 1 to 11 to enable the reader to keep track of the different voices in the empirical material.

Copyright © 2005, Idea Group Inc. Copying or distributing in print or electronic forms without written permission of Idea Group Inc. is prohibited.

Mobile IT as Immutable Mobiles? 203

MBT as a Complementary Channel between Bank and Customer

The key ambition with the service is “to bring the bank closer to the customer” (project manager). Since MBT is an offline service it can support the user wherever he/she is (e.g., on the beach, in a foreign country, or onboard an airplane) since no other infrastructure (e.g., a reliable wireless network connection to the Internet) is needed. However, to keep the data in MBT updated with the bank and transactions made the user needs to synchronize his/ her device now and then. Today, this can be easily done by just putting the PDA in its cradle, which is connected to a computer, or simply by using a mobile phone with built-in modem to call up the bank over GSM or GPRS. When a secure connection is established between the PDA and the bank server, all transactions made on the PDA is transferred to the bank and synchronized with any other transactions made (e.g., VISA card transactions, Internet bank transactions, etc.).

MBT makes it possible to do almost any kind of action that is possible to do over the Internet bank channel. However, the main advantage with the MBT is not that it supports all the online Internet services, but that it supports offline activities. For instance during flight trips, the user can manage his or her accounts and make some transfers offline and then just synchronize the information whenever its possible to connect to the Internet.

The bank saw MBT as a complementary channel to the other channels available to the customers (e.g., the bank offices, the telephone bank, the Internet bank, the ATM machines, etc.).

One of the users commented on this:

“I guess this is a good idea, and I can see myself using it if only the next version is more easy to use. It is pretty similar to the Internet bank with the difference that now I can bring this with me wherever I go.” (user 1)

Some users were concerned, however, about the benefits with a new channel:

“I just don’t see the point. To be honest, I tried to be open about this. Maybe it’s just me being, well… older than the target group,

Copyright © 2005, Idea Group Inc. Copying or distributing in print or electronic forms without written permission of Idea Group Inc. is prohibited.