Implications of the erg Theory

Managers must understand that an employee has various needs that must be satisfied at the same time. According to the ERG theory, if the manager concentrates solely on one need at a time, this will not effectively motivate the employee. Also, the frustration- regression aspect of ERG Theory has an added effect on workplace motivation. For instance- if an employee is not provided with growth and advancement opportunities in an organization, he might revert to the relatedness need such as socializing needs and to meet those socializing needs, if the environment or circumstances do not permit, he might revert to the need for money to fulfill those socializing needs. The sooner the manager realizes and discovers this, the more immediate steps they will take to fulfill those needs which are frustrated until such time that the employee can again pursue growth.

Equity Theory

Do you ever wonder what kind of grade the person sitting next to you in class makes on a test or on a major class project? Most of us do! Being human, we tend to compare ourselves with others. If someone offered you $60,000 a year on your first job after graduating from college, you'd probably jump at the offer and report to work enthusiastic, ready to tackle whatever needed to be done, and certainly satisfied with your pay. How would you react, though, if you found out a month into the job that a co-worker—another recent graduate, your age, with comparable grades from a comparable school, and with comparable work experience—was getting $65,000 a year? You'd probably be upset! Even though in absolute terms $60,000 is a lot of money for a new graduate to make (and you know it!), that suddenly isn't the issue. You see the issue now as relative rewards and what you believe is fair—what is equitable. The term equity is related to the concept of fairness and equal treatment compared with others who behave in similar ways. There's considerable evidence that employees compare their job inputs and outcomes relative to others and that inequities influence the degree of effort that employees exert.33

Equity theory, developed by J. Stacey Adams, proposes that employees perceive what they get from a job situation (outcomes) in relation to what they put into it (inputs) and then compare their inputs-outcomes ratio with the inputs-outcomes ratios of relevant others (Exhibit 16.9). If an employee perceives her ratio to be equal to those of relevant others, a state of equity exists. In other words, she perceives that her situation is fair—that justice prevails. However, if the ratio is unequal, inequity exists and she views herself as underrewarded or overrewarded. When inequities occur, employees attempt to do something about it. What will employees do when they perceive an inequity? Let's look more closely at their probable behavioral responses.

Exhibit 16.9 Equity Theory

Equity theory proposes that employees might (1) distort either their own or others' inputs or outcomes, (2) behave in some way to induce others to change their inputs or outcomes, (3) behave in some way to change their own inputs or outcomes, (4) choose a different comparison person, or (5) quit their job. These types of employee reactions have generally proved to be correct.34 A review of the research consistently confirms the equity thesis: Employee motivation is influenced significantly by relative rewards as well as by absolute rewards. Whenever employees perceive inequity, they'll act to correct the situation.35 The result might be lower or higher productivity, improved or reduced quality of output, increased absenteeism, or voluntary resignation.

The other aspect we need to examine in equity theory is who these "others" are against whom people compare themselves. The referent is an important variable in equity theory.36 Three referent categories have been defined: other, system, and self. The "other" category includes other individuals with similar jobs in the same organization but also includes friends, neighbors, or professional associates. On the basis of what they hear at work or read about in newspapers or trade journals, employees compare their pay with that of others. The "system" category includes organizational pay policies and procedures and the administration of the system. Whatever precedents have been established by the organization regarding pay allocation are major elements of this category. The "self" category refers to inputs-outcomes ratios that are unique to the individual. It reflects past personal experiences and contacts and is influenced by criteria such as past jobs or family commitments. The choice of a particular set of referents is related to the information available about the referents as well as to their perceived relevance.

10 - Definition of Organizational Culture, Characteristics and Dimensions of Culture

We know that every person has a unique personality. An individual's personality is a set of relatively permanent and stable traits. Our personality influences the way we act and interact with others. When we describe someone as warm, open, relaxed, or conservative, we're describing personality traits. An organization, too, has a personality, which we call its culture.

What is Organizational Culture?

What is organizational culture? It's a system of shared meaning and beliefs held by organizational members that determines, in large degree, how they act. It represents a common perception held by the organization's members. Just as tribal cultures have rules and taboos that dictate how members will act toward each other and outsiders, organizations have cultures that govern how its members should behave. In every organization, there are systems or patterns of values, symbols, rituals, myths, and practices that have evolved over time.4 These shared values determine to a large degree what employees see and how they respond to their world.5 When confronted with problems or work issues, the organizational culture—the "way we do things around here"—influences what employees can do and how they conceptualize, define, analyze, and resolve issues.

Our definition of culture implies several things. First, culture is a perception. Individuals perceive the organizational culture on the basis of what they see, hear, or experience within the organization. Second, even though individuals may have different backgrounds or work at different organizational levels, they tend to describe the organization's culture in similar terms. That is the shared aspect of culture. Finally, organizational culture is a descriptive term. It's concerned with how members perceive the organization, not with whether they like it. It describes rather than evaluates.

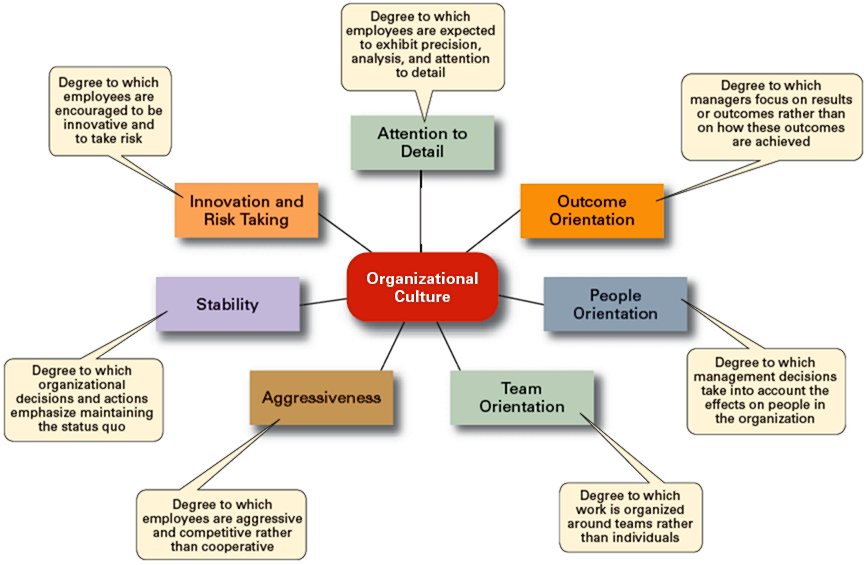

Research suggests that there are seven dimensions that capture the essence of an organization's culture.6 These dimensions are described in Exhibit 3.2. As you can see, each of these characteristics exists on a continuum from low to high. Appraising an organization on these seven dimensions gives a composite picture of the organization's culture. In many organizations, one of these cultural dimensions often rises above the others and essentially shapes the organization's personality and the way organizational members do their work. For instance, at Sony Corporation the focus is on product innovation. The company "lives and breathes" new-product development (outcome orientation), and employees' work decisions, behaviors, and actions support that goal. In contrast, Southwest Airlines has made its employees a central part of its culture (people orientation). Exhibit 3.3 demonstrates how these dimensions can be mixed to create significantly different organizations.

Exhibit 3.3 Dimensions of Organizational Culture

Strong Versus Weak Cultures

Although all organizations have cultures, not all cultures have an equal impact on employees' behaviors and actions. Strong cultures—cultures in which the key values are deeply held and widely shared—have a greater influence on employees than do weak cultures. The more that employees accept the organization's key values and the greater their commitment to those values, the stronger the culture is.

Whether an organization's culture is strong, weak, or somewhere in between depends on factors such as the size of the organization, how long it has been around, how much turnover there has been among employees, and the intensity with which the culture was originated. Some organizations do not make clear what is important and what is not; this lack of clarity is a characteristic of weak cultures. In such organizations, culture is unlikely to greatly influence managers. Most organizations, however, have moderate to strong cultures. There is relatively high agreement on what's important, what defines "good" employee behavior, what it takes to get ahead, and so forth. In fact, one study of organizational culture found that employees in organizations with strong cultures were more committed to their organization than were employees in organizations with weak cultures. The organizations with strong cultures also used their recruitment efforts and socialization practices to build employee commitment.7 And an increasing body of evidence suggests that strong cultures are associated with high organizational performance.8 What are the implications for the way managers manage? As an organization's culture becomes stronger, it has an increasing impact on what managers do.9

The Source of Culture

An organization's current customs, traditions, and general way of doing things are largely due to what it has done before and the degree of success it has had with those endeavors. The original source of an organization's culture usually reflects the vision or mission of the organization's founders. Because the founders had the original idea, they also may have biases on how to carry out the idea. Their focus might be on aggressiveness or it might be on treating employees as family. The founders establish the early culture by projecting an image of what the organization should be. They're not constrained by previous customs or approaches. And the small size of most new organizations helps the founders instill their vision in all organizational members

How Employees Learn Culture

Culture is transmitted to employees in a number of ways. The most significant are stories, rituals, symbols, and language.

Stories

Organizational "stories" typically contain a narrative of significant events or people including such things as the organization's founders, rule breaking, reactions to past mistakes, and so forth. For instance, managers at Nike feel that stories told about the company's past help shape the future. Whenever possible, corporate "storytellers" (senior executives) explain the company's heritage and tell stories that celebrate people getting things done. These stories provide prime examples that people can learn from. To help employees learn the culture, organizational stories anchor the present in the past, provide explanations and legitimacy for current practices, and exemplify what is important to the organization.

Rituals

Corporate rituals are repetitive sequences of activities that express and reinforce the values of the organization, what goals are most important, and which people are important and which ones are expendable. One of the best-known corporate rituals is Mary Kay Cosmetics' annual meeting for

its sales representatives. Looking like a cross between a circus and a Miss America pageant, the awards ceremony takes place in a large auditorium, on a stage in front of a large, cheering audience, with all the participants dressed in glamorous evening clothes. Salespeople are rewarded for their success in achieving sales goals with an array of flashy gifts including gold and diamond pins, furs, and pink Cadillac’s. This "show" acts as a motivator by publicly acknowledging outstanding sales performance. In addition, the ritual aspect reinforces founder Mary Kay's determination and optimism, which enabled her to overcome personal hardships, found her own company, and achieve material success. It conveys to her salespeople that reaching their sales goals is important and that, through hard work and encouragement, they too can achieve success. Your second author had the experience of being on a flight out of Dallas one year with a planeload of Mary Kay sales representatives headed home from the annual awards meeting. Their contagious enthusiasm and excitement made it obvious that this annual "ritual" played a significant role in establishing desired levels of motivation and behavioral expectations, which, after all, is what an organization's culture should do.

Material Symbols

When you walk into different businesses, do you get a "feel" for the place—formal, casual, fun, serious, and so forth? These feelings you get demonstrate the power of material symbols in creating an organization's personality. The layout of an organization's facilities, how employees dress, the types of automobiles top executives are provided, and the availability of corporate aircraft are examples of material symbols. Others include the size of offices, the elegance of furnishings, executive "perks" (extra "goodies" provided to managers such as health club memberships, use of company-owned resort facilities, and so forth), the existence of employee lounges or on-site dining facilities, and reserved parking spaces for certain employees. These material symbols convey to employees who is important, the degree of equality desired by top management, and the kinds of behavior (for example, risk taking, conservative, authoritarian, participative, individualistic, and so forth) that are expected and appropriate.

Language

Many organizations and units within organizations use language as a way to identify members of a culture. By learning this language, members attest to their acceptance of the culture and their willingness to help to preserve it. For instance, Microsoft, the software company, has its own unique vocabulary: work judo (the art of deflecting a work assignment to someone else without making it appear that you're avoiding it; eating your own dog food (a strategy of using your own software programs or products in the early stages as a way of testing them even if the process is disagreeable); flat food (goodies from the vending machine that can be slipped under the door to a colleague who's working feverishly on deadline); facemail (actually talking to someone face-to-face; considered by Microsoft employees a technologically backward means of communicating); death march (the countdown to shipping a new product); and so on.

Over time, organizations often develop unique terms to describe equipment, key personnel, suppliers, customers, or products that are related to their business. New employees are frequently overwhelmed with acronyms and jargon that, after a short period of time, become a natural part of their language. Once learned, this language acts as a common denominator that unites members of a given culture.

11 –Communication (Lecture Notes):

The importance of effective communication for entrepreneurs can't be overemphasized for one specific reason: Everything a entrepreneur does involves communicating. Not some things, but everything! A entrepreneur can't make a decision without information. That information has to be communicated. Once a decision is made, communication must again take place. Otherwise, no one would know that a decision was made. The best idea, the most creative suggestion, the best plan, or the most effective job redesign can't take shape without communication. Entrepreneurs need effective communication skills. We aren't suggesting, however, that good communication skills alone make a successful entrepreneur. We can say, though, that ineffective communication skills can lead to a continuous stream of problems for a entrepreneur.

What is Communication?

Communication is the transfer and understanding of meaning. The first thing to note about this definition is the emphasis on the transfer of meaning. This means that if no information or ideas have been conveyed, communication hasn't taken place. The speaker who isn't heard or the writer who isn't read hasn't communicated. More importantly, however, communication involves the understanding of meaning. For communication to be successful, the meaning must be imparted and understood. A letter written in Portuguese addressed to a person who doesn't read Portuguese can't be considered communication until it's translated into a language the person does read and understand. Perfect communication, if such a thing existed, would be when a transmitted thought or idea was perceived by the receiver exactly as it was envisioned by the sender.

Another point to keep in mind is that good communication is often erroneously defined by the communicator as agreement with the message instead of clearly understanding the message.3 If someone disagrees with us, many of us assume that the person just didn't fully understand our position. In other words, many of us define good communication as having someone accept our views. But I can clearly understand what you mean and just not agree with what you say. In fact, many times when a conflict has gone on a long time, people will say it's because the parties aren't communicating effectively. That assumption reflects the tendency to think that effective communication equals agreement.

The Communication Process

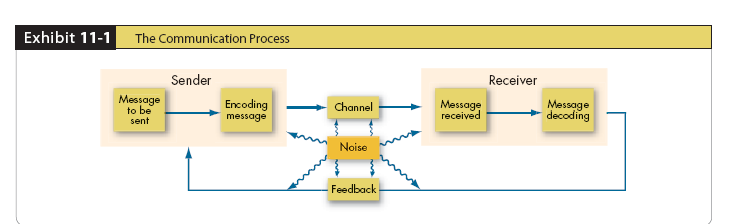

The Process of Interpersonal Communication

Before communication can take place, a purpose, expressed as a message to be conveyed, must exist. It passes between a source (the sender) and a receiver. The message is converted to symbolic form (called encoding) and passed by way of some medium (channel) to the receiver, who retranslates the sender's message (called decoding). The result is the transfer of meaning from one person to another. Exhibit 11.1 illustrates the seven elements of the communication process: the communication source, the message, encoding, the channel, decoding, the receiver, and feedback. In addition, note that the entire process is susceptible to noise—disturbances that interfere with the transmission, receipt, or feedback of a message. Typical examples of noise include illegible print, phone static, inattention by the receiver, or background sounds of machinery or co-workers. Remember that anything that interferes with understanding can be noise, and noise can create distortion at any point in the communication process. Let's look at how distortions can happen with the sender, the message, the channel, the receiver, and the feedback loop.

A sender initiates a message by encoding a thought. Four conditions influence the effectiveness of that encoded message: the skills, attitudes, and knowledge of the sender, and the sociocultural system. How? We'll use ourselves, as your textbook authors, as an example. If we don't have the requisite skills, our message won't reach you, the reader, in the form desired. Our success in communicating to you depends on our writing skills. In addition, any preexisting ideas (attitudes) that we may have about numerous topics will affect how we communicate. For instance, our attitudes about entrepreneurial ethics, labor unions, or the importance of entrepreneurs to organizations influence our writing. Next, the amount of knowledge we have about a subject affects the message(s) we are transferring. We can't communicate what we don't know; and if our knowledge is too extensive, it's possible that our writing won't be understood by the readers. Finally, the socio-cultural system in which we live influences us as communication senders. Our beliefs and values (all part of culture) act to influence what and how we communicate.

The message itself can distort the communication process, regardless of the kinds of supporting tools or technologies used to convey it. A message is the actual physical product encoded by the source. It can be the written document, the oral speech, and even the gestures and facial expressions we use. The message is affected by the symbols used to transfer meaning (words, pictures, numbers, etc.), the content of the message itself, and the decisions that the sender makes in selecting and arranging both the symbols and the content. Noise can distort the communication process in any of these areas.

The channel chosen to communicate the message also has the potential to be affected by noise. Whether it's a face-to-face conversation, an e-mail message, or a company-wide memorandum, distortions can and do occur. Entrepreneurs need to recognize that certain channels are more appropriate for certain messages. Obviously, if the office is on fire, a memo to convey that fact is inappropriate! And if something is important, such as an employee's performance appraisal, a entrepreneur might want to use multiple channels—perhaps an oral review followed by a written letter summarizing the points. This decreases the potential for distortion.

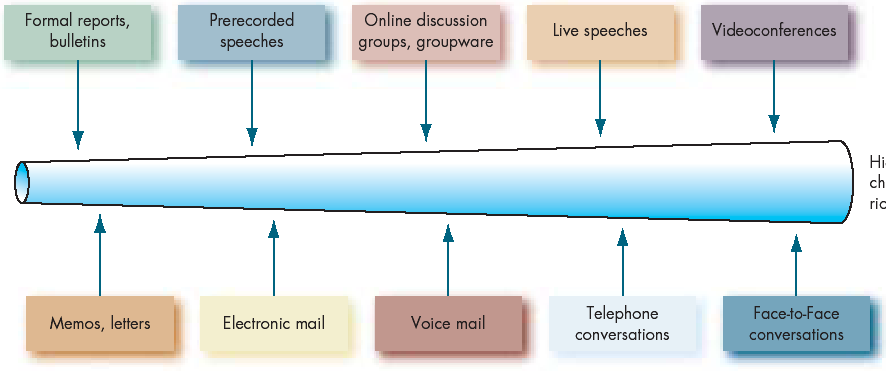

Channel Richness

The amount of information that can be transmitted during a communication episode.