COMPARATIVE HISTORY OF

INTELLECTUAL COMMUNITIES

Part II: Western Paths

£

C H A P T E R 8

£

Tensions of Indigenous and Imported Ideas:

Islam, Judaism, Christendom

Philosophy in the medieval societies of the West built on earlier cultural capital. In the long historical view, we are tempted to skip over that which is derivative and to concentrate on that which is originating. Our deprecating image is an unsophisticated society overwhelmed by imports from a previous civilization and unable to get its own creativity off the ground. The image is doubly misleading.

Importing ideas has its own intellectual rhythm: passive at first, it is capable of turning into the normal creative process within a few generations. We see this in the Buddhist philosophies of medieval China, where the receiving environment already had a well-established tradition of literate culture—no peripheral region here overwhelmed by sophisticated imports. In the regions of Islam and European Christendom, the imports came into tribal societies newly organized into state and church. What made their philosophies distinctive in quality was not so much their initial dependence on imports—which in the case of Christendom was repetitively dependent, repetitively importing ideas from other civilizations, including Islam—as that the receiving context was dominated by a politically powerful religion. Idea imports are tagged for their relevance or opposition to religious orthodoxy.

Such a situation is ready-made for a Whiggish interpretation of intellectual history, in which defenders of tradition battle against openness to new ideas. But openness to new ideas initially takes the form of adulation of old ideas, hardly creative in its own right. Our received tradition of a Greeks-to-Arabs- to-Christians sequence imposes a second kind of blindness. We miss the opportunity to peer into the cauldron where indigenous intellectuals develop their own disputes. Starting from religious-political disputes, the Muslims drove up the level of abstraction and revealed the ontological and epistemological issues which are distinctive to monotheism. Imports are rarely passive; indigenously developed factions have their own motivations for seeking out imports and reacting to what comes in. Our aim must be to look at the creative and un-

387

388 • I n t e l l e c t u a l C o m m u n i t i e s : We s t e r n Pa t h s

creative aspects of idea imports, in the usual context of multi-sided intellectual conflict which drives creativity everywhere. The viewpoint will give us an unexpected bonus: we will see that not only importing but also exporting ideas to an eager recipient can stimulate its own form of creativity.

Philosophy within a Religious Context

What difference does it make when intellectual communities arise as offshoots of religious organization? One might suppose that this circumstance affects only arbitrary aspects of the context of thought. Once an intellectual network becomes organized, it generates its own problems and standards. Intellectuals competitively appropriate whatever cultural capital exists, and will produce contrasting positions by the dynamics of creation through opposition. The QurÁan, the Bible, the Vedic hymns, the sayings of the Buddha are so many starting points which become increasingly overlaid by the accumulated debates of generations of intellectuals. Abstract issues of metaphysics and logic emerge and become autonomous questions in their own right: religion spawns philosophy.

Religious doctrines are put forward as charismatic revelation or as inalterable tradition; they are to be learned, recited, and put into practice as guides for ritual or for living. They are not, on the face of it, subjects for discussion and intellectual development. There is a limited exception in the period when a religion first assembles its written canon, for example, the period ca. 150–200 c.e. (Aland and Aland, 1987) when the Christian Gospels, letters of Saint Paul, and a few other texts of the founding generations were accepted as holy scripture while other candidate texts were excluded, along with rival organizations (such as the Gnostic circles) which carried them. Similarly in Islam, the generations after the death of Muhammad were devoted to the redaction of Muhammad’s revelations (the QurÁan, ca. 632–656) and to compiling (which went on into the mid-800s) hadith, the recollections of the Prophet’s companions used as alternate sources of legal tradition (Watt, 1985: 57; Lapidus, 1988: 103–104). Beyond this point the canon is closed, and the activities of the scholars should now be reduced to a simple transmission of the received word.

The extent to which this closure happens is a sociological phenomenon in its own right. Quasi-canonical literature may continue to grow, if the religion lacks an authority which monopolizes the definition of the holy texts. Buddhist sutras claiming the status of charismatic revelations and bolstered by allegations of antiquity continued to appear for many centuries, from 400 b.c.e. down to 300 c.e. and later (Conze, 1962: 200). The Hindu world was extremely decentralized after the breakdown of the old Vedic priest guilds; scriptural status could be claimed not only for later commentaries and super-

Tensions of Ideas: Islam, Judaism, Christendom • 389

commentaries on the Vedic hymns, but also for new mythological collections (the Puranas down through 1500 a.d.) and poetic epics (the Mahabharata ca. 300 b.c.e.–300 c.e., and the Ramayana ca. 200 b.c.e.–200 c.e.; O’Flaherty, 1975: 17–18). Judaism, after the destruction of the Jerusalem temple in 70 c.e. and the dispersion of Jewish communities, developed an accretion of religious law and interpretation, the Mishnah, which was collected and codified in several editions between 200 and 500 c.e. (Segal, 1986: 16, 133–136). The Talmudic literature of the famous teachers continued to grow; the systematizing efforts of Maimonides and his successors around 1200 attempted again to reduce this material to a simpler conception of orthodoxy, but there was no agency to enforce it.

Christianity and Islam stand out because the organizational conditions were present relatively early to close their holy canons.1 It was here that the relations between religion and philosophy became explicitly an issue. In these circumstances a crucial topic of philosophy must be the relationship between “faith” and “reason.” This in turn gave impetus to questions of epistemology. When religion is armed with coercive political power, the range of answers is limited; the prudent thinker is forced to claim either that reason and faith harmonize, or if they do not, that faith is superior. Bold advocates of the independence of philosophy, if protected by enough organizational insulation, or if they find chinks in the system of political enforcement, might push the border.

The philosophical path which starts here may continue farther. A crucial push is given when such epistemological issues are taken up by theological conservatives. Once elaborate metaphysical constructions are produced across several generations of philosophers, the intellectuals who are closest to the space of conservative dogmatism can turn philosophical sophistication against itself by raising the epistemological level, and can question the validity of arguments within the realm of reason itself. We find this in Islam with alGhazali and Ibn Taymiyah, and in Christendom with the conservative condemnations of 1277 leading to the refined positions of Scotus and Ockham. If the philosophical community continues under religious challenge, further positions are generated, and the field is propelled into a full-fledged epistemology. This is much more apparent in Christendom than in Islam, where the fundamentalist attacks increasingly constricted the philosophers, and the sophisticated conservatives themselves lacked technically oriented followers; the significance of the issue disappeared with their opponents. The result was reinforced because of the tendency of later Islamic intellectuals to take refuge in a secret doctrine accessible to the initiates of reason, while scripture was taken as metaphoric expression for the crude masses. This removed the creative tension of argument with the orthodox; the esotericism of later Islam turned to a poetic mysticism, and away from the analytical issues of epistemology.

390 • I n t e l l e c t u a l C o m m u n i t i e s : We s t e r n Pa t h s

This devious path from enforced doctrinal orthodoxy to critical epistemology is not found unless religion is state-enforced. This route toward epistemological issues did not exist in China, where the state usually supported all manner of ritualistic exercises, in a kind of pluralistic tolerance. There was no sacred scripture to be officially enforced; the nearest thing to it was the Confucian texts, but these were held to be products of human reason, and thus on the side of philosophy. Taoist religion by the late 400s c.e. claimed its texts to be charismatically revealed, but political weakness prevented Taoists from elevating them to uniquely enforced scriptural truth. It follows that if the Taoist church had acquired long-term political power, its relations with non-dogmatic intellectuals would also have given rise to epistemological issues. The same should have happened if Buddhism had continued as the state religion beyond its short episodes of imperial favor in the T’ang.2

The initial effect of religion on philosophy is not to produce epistemological controversy; that tends to come later as philosophers build up their own positions. Initially the religion sets forth a content on which intellectuals may work. The Western religions begin with a pre-reflective anthropomorphism. God is a person, possessing human attributes such as knowledge, power, goodness, and will, raised of course to a superlative degree. God creates the physical world, and will bring it to an end, much as any human could manufacture an object and then destroy it. Islam includes other supernaturally endowed persons: the Prophet and various angels, with their missions and announcements. Christianity in some ways redoubles the anthropomorphic elements, focusing not only on God but also on Christ, who is both a man and Son of God; on the miraculous elements of his virgin birth (which thereby elevate the person of his miraculous mother) and his crucifixion and resurrection; the doctrine of human sin and redemption, the Day of Judgment, and the resurrection of human bodies to eternal life in heaven or hell. Human events are given cosmic significance; conversely, the cosmos is tied to a personal scale.

Such doctrines give rise to problems if the church, as a social organization carrying out rituals and justifying them by faith in holy scripture, declares that the texts are to be taken in a literal, commonsensical way. Originally it is not laypersons who question the literal meaning of these doctrines; it is, after all, the miraculous aspect of this picture that makes it so impressive for ordinary people. It is the specialists within the church entrusted with the care and teaching of the holy documents, who feel a need to reduce the anthropomorphic elements because of their sophisticated conception of religious impressiveness. If God is superlative in every respect, how can he have merely physical qualities? The QurÁan speaks of God sitting on his throne; the early theologians argued that this is only a metaphor for his grandeur. In response the conservative legalist Malik thundered: “The sitting is given, its modality is unknown.

Tensions of Ideas: Islam, Judaism, Christendom • 391

Belief in it is an obligation and raising questions regarding it is a heresy” (Fakhry, 1983: xvii). But Malik, against his own intentions, was thereby staking out one of the corners of philosophical turf. The Muslim intellectual community went on for generations after this, taking various sides on the issues which arose directly out of the anthropomorphic scripture: the responsibility of humans as against the providence and power of God, and then to more metaphysical issues surfacing in these discussions.

Various philosophical issues are provoked by anthropomorphic religion which are not shared by more cosmologically oriented religions such as Confucianism, Taoism, or Indian mysticism. The philosophical confrontation with anthropomorphism focused attention on the nature of transcendence and infinite perfection and their relations to limitation and contingency. The issue of free will arose distinctively in the West, not in India or China, and with it the nature of causality and determinism. It is the character of the oppositions generated by religious doctrine, as much as the slant of that doctrine itself, that is fateful for the trajectory of philosophical problems.

It is distinctive of the Western religions, not the Eastern, that philosophers devoted much effort to proofs of the existence of God. Such proofs from a religious viewpoint are superfluous; the philosophers were not free in any case to consider whether God does not really exist. The justification was sometimes offered that proofs were needed in order to convince unbelievers or convert members of other faiths, but this seems a patent rationalization: Christians, Muslims, and Jews could not convert one another by proving the existence of God, since all three faiths admitted this, and the differentiating items of faith were not proved in this fashion;3 and atheist unbelievers were an imaginary foil under these authoritarian regimes. The philosophers’ construction of proofs for items of faith was a matter of creating a turf for pure intellectual activity within the institutional space of the religious schools. These proofs became grounds on which metaphysical and epistemological doctrines could be worked out. With a sufficiently complex network of philosophers, such as arose in Christendom by the late 1200s, it was no longer a foregone conclusion that one would have to succeed in proving the existence of God or the immortal soul. By the time of Ockham and his followers, it was acceptable to conclude that these items could not be conclusively proved by reason; this was taken as demonstrating the superior power of faith, and also of demarcating the territory of distinctively philosophical techniques.

The religious communities did not set out to have philosophies. Virtually all of them began with the notion that intellectual life is superfluous, indeed an obstacle to religious devotion. But the very structure of having specialists in sacred texts created an intellectual community with its own dynamics. Greater abstraction and self-reflectiveness about one’s own tools was one of

392 • I n t e l l e c t u a l C o m m u n i t i e s : We s t e r n Pa t h s

the weapons which the intellectual community forged in order to carry out its struggles over the turf of theology. By a further twist of organizational development, the more abstract topics could become a focus in themselves. This was not without dangers from the political arm of the church. Philosophical insiders pursuing the logic of debate on questions such as free will or the attributes of God could find themselves entangled in heresy disputes with theologians. Such accusations and condemnations ring right through medieval Christian and Muslim philosophy. From one angle they certainly represent the chilling hand of power upon intellectual autonomy. But condemnations in themselves do not distinguish between periods of creativity or stagnation; creative philosophers were just as likely to accuse their own opponents of heresy. The distinctive philosophies of the West are those which were wrung out through these channels of conflict; the danger was a cost of the creativity.

The Muslim World: An Intellectual Community

Anchored by a Politicized Religion

Islam begins as a theocracy. Here theological factions are always in the first instance political factions; to claim theological orthodoxy is the same as claiming political rulership of the Islamic state. After Arabian military conquests swept the Middle East in the generation after Muhammad (taking Syria, Egypt, Iraq, and Persia between 634 and 654), Islamic warriors fractionated along lines of charismatic succession to the rulership. The line divided supporters of the winners and of the losers in the civil wars of the succession: roughly, the position eventually known as Sunnites, who accepted the political status quo and the victorious lineage, and the ShiÀites, intransigents who held out loyally for the family line of the losing faction. On each side in turn there was further fractionation. The victorious majority developed a pragmatic group who offered compromise with the losers, in effect declaring its willingness not to pursue the old issues of legitimacy and illegitimacy of various claims. On the ShiÀite side, the more vehement rebels were eventually displaced by a faction which held that the Imam, the true successor to the Prophet was in hiding. This gave a somewhat otherworldly tone to the expectation that in some future generation the correct theocratic lineage would reappear, and it allowed Imamites to operate as a spiritual sect within the Islamic state without necessarily rebelling against it politically. Other ShiÀite factions remained more militant, sometimes winning political power in particular states.

Islamic factions became a reflex of geopolitics and revolutionary success. The initial wave of conquests, uniting the tribes of Arabia, swept into the power vacuum created by the stalemate between the Byzantine and Sassanian Persian empires. The ÀAbbasid caliphate consolidated power after three civil

HEIGHT OF THE ‘ABBASID CALIPHATE, 800 C.E.

394 • I n t e l l e c t u a l C o m m u n i t i e s : We s t e r n Pa t h s

wars, and from 750 administered an empire centralized at Baghdad.4 After 830 the caliphate began to lose de facto power to regional administrators, and full-fledged independent states divided the region between 950 and 1200. These in turn became subject to waves of imperial conquest; the most successful were the Seljuk Turks around 1040–1100; the Mongol conquerors 1220–1260, who soon converted to Islam and split into smaller states; and the Ottomans, who expanded from Asia Minor from the 1360s. Some of the ShiÀite factions acquired state power, notably the IsmaÀili activists in Egypt, 970–1170. Winners and losers, orthodox and anti-orthodox traded places on a geopolitical checkerboard.

The principal consequence for intellectual life was that Islamic religion never acquired a centralized church organization. According to theocratic tradition accepted by all factions, the caliph was successor to the Prophet and leader of the faithful; but his legitimacy was questioned by important factions ever since the early generations of Islam, and was further broken up with the dispersion of political power. De facto religious authority devolved into the hands of the Àulama, or religious scholars. As befits a theocracy, the law was the religious law, and the religious schools in effect monopolized the activities of law courts as well. Orthodox religious scholars were quasi-independent of the state, without forming an organized church comparable to the Christian papacy. Only the ÀAbbasid caliphate at its height had enough power to attempt uniform control of religious life; the powerful caliph al-MaÁmun (r. 813–833) and his successors attempted to impose doctrinal orthodoxy on all Muslim scholars. But this inquisition on behalf of caliphal power was resisted, and finally abandoned in 848 as the caliphate began to disintegrate; thereafter the Àulama dominated religious law and doctrine without challenge.

Insofar as the schools of the Àulama were centers of intellectual life, they were anchored in the particularistic concerns of daily ritual, holy texts, and practical law. Although more abstract consideration of theology did emerge from this base, it was continually open to attack. More detached intellectual life was supported by patronage of the political rivals of the Àulama, especially the courtly circles around a political ruler. Precisely because the ruler at Baghdad or Córdoba was a theocrat manqué whose religious claims were always overshadowed by the truly devout of the religious schools, court circles could tend toward the opposite pole of speculation or occasionally downright secularism. This kept intellectual life in a precarious situation, at the mercy of geopolitical events that might overthrow a particular regime. The high point of the non-religious philosophers was under the patronage of the ÀAbbasids at Baghdad, and faded with the loss of protection after 950. One mitigating factor was the existence of secret societies. Although these were predominantly political and religious in their concerns, the secret societies were always

Tensions of Ideas: Islam, Judaism, Christendom • 395

in opposition to at least some part of the status quo around the Islamic world; and they sometimes looked for allies among unorthodox factions on the intellectual front. Thus one could find unholy alliances between IsmaÀili or Imamite conspirators and hard-pressed rationalist theologians and philosophers.

Four Factions

Fractionation of the intellectual field moved slowly at first, then picked up speed in the generations after 800. Four main groups of intellectuals gradually formed, three of them religious, one secular. First came the practitioners of rational theology, kalam, of which the most important group was the MuÀtazilites; in opposition emerged the scriptural literalists. In addition there were the Sufi mystics, and on the secular side, the translators and practitioners of Greek and other foreign science and philosophy, falsafa.5

Indigenous Theological Philosophers

The prevailing attitude of intellectual historians is that only the Greek falasifa (philosophers) are worth paying attention to, since it was they who transmitted the main line of European philosophy. These blinders prevent us from seeing what is more significant: the dynamics by which Islamic theologians broke into philosophical terrain of their own accord. Indigenous theological disputes, like any other sustained intellectual conflict, spontaneously drive up the level of abstraction and uncover issues of metaphysics and epistemology. We have a laboratory for how philosophy emerges nearer to us than the obscure beginnings of the Chinese, Indians, and Greeks, as well as a picture of the independent path by which were created positions paralleling those of later European developments at the time of Descartes, Locke, and Malebranche.

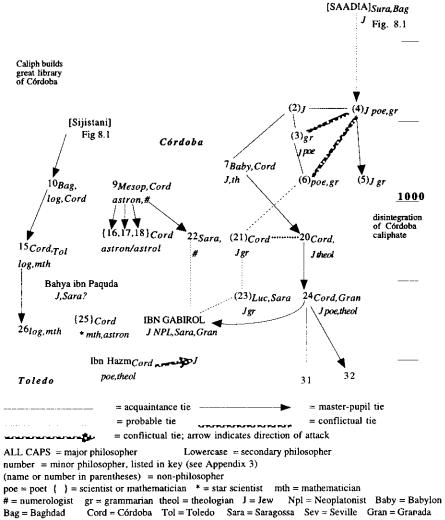

The first notable intellectuals appeared in the early 700s (see Figure 8.1). At first there was an undifferentiated style of scriptural scholar, such as Hasan al-Basri, who was famous for his pronouncements in law as well as theology, and was claimed as a predecessor to the Sufis for his asceticism. In the next two generations the field began to crystallize into factions. The early center of theological discussion was at Basra, founded by the Arab conquerors in the Mesopotamian river delta. When Baghdad was founded in the 760s as the capital for the new ÀAbbasid caliphate, these two cities about 250 miles apart became the twin centers of intellectual life, displaying the familiar pattern of intersecting networks circulating at rival centers.

The earliest issues emerged out of religious politics. On one front there was a dispute between predestination and free will, on the other flank the question of the unity of God as against dualism or anthropomorphism. Predestination

396 • I n t e l l e c t u a l C o m m u n i t i e s : We s t e r n Pa t h s

FIGURE 8.1. ISLAMIC AND JEWISH PHILOSOPHERS AND SCIENTISTS, 700–935: BASRA AND BAGHDAD SCHOOLS (all at Baghdad unless marked)

Tensions of Ideas: Islam, Judaism, Christendom • 397

had become an issue because of an early political dispute over the legitimacy of the caliphate. The succession had been won by violence and treachery, and some Islamic factions held that sins such as these make one cease to be a Muslim and render a ruler subject to overthrow. Those willing to accept the status quo tended to accept as well the argument that the caliph’s acts were predestined. Free will was accordingly condemned as an incitement to rebellion. As late as 743 some advocates of free will were executed by the caliph. This political connection was ephemeral. Within a few generations the political implications had been reversed; for a period in the 800s the MuÀtazilite advocacy of free will was put forward as orthodoxy by the caliphate.

A faction was formed at the mosque at Basra out of those who took an intermediate position on the debate over sinners—the issue implying how much loyalty one must give to a sinful caliph. A further split reacted against the theological moderation of Hasan al-Basri; this faction stressed the predestination of human acts and the omnipotence of God so strongly as to hold that actions can be imputed to humans only figuratively. Intellectual debate was now driving positions to extremes. The next step was the MuÀtazilite defense of free will, the typical pattern of intellectual development through escalating conflict between opposite sides of the field. The defenders of free will were forced to elaborate their position, declaring that God does no evil. This led to a recognition that the standards of good and evil are not conventional or arbitrary. To reconcile this stance with the power of God, these theologians concluded that God has a rational nature, and that moral laws are part of this unchangeable essence of reason.

This was one route which led from literal scriptural piety into a philosophical metaphysics. Joining it was another stream of argument over the unity and attributes of God. The MuÀtazilite faction forming at Basra and Baghdad entered into a multi-fronted war against rival theologies, attacking the Zoroastrian and Manichaean dualists (the former the traditional religion of Persia, now under Islamic conquest; the latter a Christian heresy centered in Mesopotamia) as well as the Trinity of the Christians (widespread in the Islamic domains of Iraq, Syria, and Egypt). This controversy led to proofs that there is only one God, undivided and without plurality. The MuÀtazilites became famous for their proofs, not only of the unity of God but also of the createdness of the world, and thus of the existence of the Creator as well. Theology became rationally defended and set on the path to where reason itself could be exalted above scripture and revelation. The MuÀtazilite proofs were adopted wholesale by contemporary Jewish thinkers who became the first notable Jewish philosophers of the Middle Ages.

Both Muslim and Jewish practitioners of kalam, or rational theology, argued for the harmonization of rational proofs with their scriptural doctrines.

398 • I n t e l l e c t u a l C o m m u n i t i e s : We s t e r n Pa t h s

The MuÀtazilites met opposition from the faction of Islamic scriptural literalists crystallizing at the same time, and were goaded into a more uncompromising stand (Hodgson, 1974: 1:386–389). The hadith scholars were fighting for their own brand of scripturalism, attempting to formulate alongside the QurÁan a canon of the recollections of Muhammad’s companions; their stance exalted the status of scriptures over everything else. They attacked the application of personal judgment in legal cases; the doctrine of free will, as limiting the powers of God; and the unity of God because it contradicts the personal and even physical attributes of God, which are mentioned in scripture. The rational theologians, who had been arguing for the metaphorical nature of these passages, were driven onto more extreme grounds. Adopting Aristotelean language, they held that God is a substance of absolute unity and simplicity, and that there are no attributes apart from his essence.

Defenders of kalam now took the offensive against the hadith scholars. Marshaling their arguments for the unity of God, they held that the QurÁan is a created object, not an eternal truth; to elevate scripture to a holy object, co-eternal with God, is to fall into dualism, even idolatry. This stance undercut the status claims of the hadith scholars as keepers of the primary cult object of Islam. Charges and counter-charges of either anthropomorphism or blasphemy eventually led to a political showdown between the two camps.

A clearly identified MuÀtazilite school emerged out of the disputes among kalamite factions in the two generations from Dirar and his contemporary MuÀammar ibn ÀAbbad in the late 700s, to Abu-Àl-Hudhayl, Bishr ibn alMuÀtamir, and al-Nazzam shortly after 800. They are connected in a network of masters, pupils, and rivals, and split into the schools of Basra and Baghdad. Abu-Àl-Hudhayl became the great systematizer, laying out the main points of MuÀtazilite orthodoxy, stressing the unity and justice of God, and as its corollary free will. To this other MuÀtazilites added the createdness of the QurÁan, and the doctrine that everything exists only as attributes of atoms in time, and must be continually re-created.

Why did the Arab theologians develop time-atomism? The influence of Greek philosophical texts at this moment is hardly a sufficient explanation.6 Why should the Arab thinkers have adopted a doctrine which was opposed by all the Greek authorities then being introduced? Moreover, time-atomism was by no means an ontological support for their major theological doctrine, the defense of free will, since perishing atoms require God’s continuous intervention. Neither of these external influences, Greek imports or theological politics, explains the line of intellectual development. What seems to have happened is this. The attempt to support free will led to refinements in the theory of causality, ways in which God could be kept clear of direct responsibility for what happens in the world. The other theological question, the unity of God

Tensions of Ideas: Islam, Judaism, Christendom • 399

(and the related issue of the createdness of the QurÁan), led to consideration of substance and attributes. The combination of these two issues generated a new intellectual space. Muslim philosophers began to compete for attention by innovating over their own problems. By taking apart the notions first of attributes, then of substance, they arrived at the doctrine of atomism. At this point a true intellectual competition existed. Islamic philosophy swung free from being a mere reflex of political positions and onto an autonomous path.

Fueled at first by theological energies, the philosophical arguments became more subtle. The Aristotelean concepts of substance and accident were subjected to scrutiny in the generation just before 800. At Basra, Dirar ibn ÀAmr rejected the notion of substance; he held that a body is a collection of accidents, arranged in a hierarchy; once constituted, an accident may become the substratum of other accidents (Fakhry, 1983: 53; Watt, 1973: 194–195). Perhaps Dirar’s contemporary Hisham ibn al-Hakam (22 in the key to Figure 8.1) had driven him to this position; Hisham held that there is no distinction of substance and accident, since every substance is divisible ad infinitum. Hisham was an avowed anthropomorphist, defending the literal descriptions of God in the QurÁan; since attributes (or accidents) were at issue, he was willing to reduce everything to an attribute. Some of the MuÀtazilites (e.g., 30 in Figure 8.1) adopted the same position. Substance was dissolving; out of this came the distinctive MuÀtazilite metaphysics, time-atomism.

Dirar was also struggling for a way to defend free will; he held that God controls what happens in the outer world, but man, not God, acquires the moral responsibility by inward assent or dissent (Fakhry, 1983: 48–49). Dirar’s solution was apparently controversial among his contemporaries, for he was attacked as a determinist. He held that there is no bodily substance but only accidents, and these cannot exist for two successive moments; this implied that they are continuously re-created by God. This is the first mention of time-at- oms, as yet applied only to attributes rather than substances.

A rival stance was taken by another Basra theologian, MuÀammar. Far from eliminating substance, MuÀammar held that God brought about the original existence of bodies by creating the atoms they are composed of (Wolfson, 1976: 158, 560–576; Peters, 1968: 144). Accidents are caused in turn by the aggregation of bodily atoms. God thus causes accidents only indirectly, and is not responsible for their good or evil qualities. For MuÀammar, man is an immaterial, knowledgeable substance connected to the body. Free will exists only inwardly; the body is part of the external world, subject to the necessity of nature. It is a dualism not unlike Descartes’s.

So far, Dirar has no atomic substance but only attributes which are temporal atoms. MuÀammar has atomic substances, although they are not timeatoms, but are permanent once created by God. The next generation appears

400 • I n t e l l e c t u a l C o m m u n i t i e s : We s t e r n Pa t h s

to have developed a thoroughgoing atomism. Abu-Àl-Hudhayl, who successfully systematized the MuÀtazilite theological position, produced an influential compromise among the ontological positions. He declared that some, but not all, accidents exist for only a moment in time; if they are to appear again for a second moment, they must be created afresh by God (Watt, 1985: 53; Wolfson, 1976: 531–532). This applies above all to the accidents of will and motion, that is, those qualities which are involved in action in the world, and hence are implicated in the question of moral responsibility. By contrast, AbuÀl-Hudhayl, along with many other MuÀtazilites, reserved certain features of the physical and spiritual world for the category of durable accidents, including color, life, and knowledge (Fakhry, 1983: 54); presumably this was in order to preserve a responsible human entity across moments of time. God causes both the duration and the destruction of accidents; this in turn raised the question whether duration and destruction are themselves accidents which exist in a spatial substratum. Secondary metaphysical problems were emerging, and the ontological status of existence and change became a topic of debate.

In this same generation a rival MuÀtazilite school formed at Baghdad, led by MuÀammar’s pupil Bishr al-MuÀtamir. Bishr gave a more realist ontological slant to time-atomism. Even though God continuously intervenes in creating and destroying attributes, every creation of existence involves a real duration, and every destruction is a real action too (Wolfson, 1976: 522–543). God creates these time-atoms out of nothing. But (according to later commentators) this MuÀtazilite school held that “nothing” is also a substantive “something”; this implies that God creates things out of a pre-existent matter.

The atomist position was not yet settled. The most radical of the MuÀtazilites, al-Nazzam, kept up Dirar’s attack on substance. Al-Nazzam argued that substance does not exist, since it can be infinitely divided. The more moderate MuÀtazilites had taken this argument only to a point; they were willing to reduce attributes to instants in time, without duration, and to reduce substance to atoms (though disputing whether they were with or without size). Al-Naz- zam pushed onward, into an extreme time-phenomenalism: there exists nothing but accidents, and none of these are durable. All other accidents reduce to the accident of motion, which is inherently transitory (Fakhry, 1983: 49–51, 215–6; Wolfson, 1976: 514–517). Al-Nazzam’s Heraclitus-like position led to difficulties of the sort raised by the Eleatics. Since a distance consists of an infinite number of points, how is it possible to traverse all of them and arrive anywhere? Al-Nazzam attempted to overcome this Zeno-like paradox by proposing a process of “leaps” from one atomic point to another over the intervening points. His doctrine of perpetual motion also had difficulties in explaining the apparent rest of bodies in one place; al-Nazzam countered this by arguing that rest consists in bodies moving into the same place twice in succession.

Tensions of Ideas: Islam, Judaism, Christendom • 401

Al-Nazzam was among the most creative of these philosophers, and also the most extreme; on the issue of the createdness of the QurÁan, he held that it cannot even resemble the transcendent word of God (Wolfson, 1976: 274– 275). He died just before the great crisis affecting the MuÀtazilites, which threw them from political favor into unorthodoxy. Al-Nazzam was attacked by orthodox MuÀtazilites and scripturalists alike. His doctrines do not appear to have had any immediate followers, and the MuÀtazilites gathered together in defense of their more moderate atomism. Some versions of time-atomism also held that the atoms are bearers of accidents which exist Platonically, apart from the realm of time (Fakhry, 1983: 216). Later doctrines were to dispute whether any accidents are exempt from existing as time-atoms continually recreated by God. It is not clear whether AbuÀl-Hudhayl held that substances as well as accidents are atomic time-instants; but by the early 900s, the Baghdad MuÀtazilite al-KaÀbi (109 in Figure 8.1) was holding that every substance and accident must be created afresh every moment by God (Watt, 1973: 301–302). This emphasis on God’s direct causality put increasing strain on the doctrine of free will. At this moment, the AshÀarite camp broke away and produced a more politically respectable version of MuÀtazilite time-atomism.

Scriptural Anti-rationalists

Islamic thought was by no means primordially scriptural and conservative. Literal defenders of holy scripture emerged gradually, in increasing polarity with the rational theologians. There were hundreds of schools of scriptural specialists across the Islamic Empire, dispensing religious law for local concerns (Makdisi, 1981: 9). Their practical orientation kept their work relatively concrete and unintellectual; abstract theological issues were not their main interest, except insofar as these were points of political significance. The rational theologians who emerged at the mosque at Basra and then at Baghdad were initially part of this same undifferentiated occupation of learned Àulama. Some of them became caught up in a network of argument which pushed the politically significant issues onto abstract grounds, and thence into philosophical constructions which took on attention in their own right; others, including many followers of Hasan al-Basri himself, joined the hadith specialists. The emerging argument among these factions gradually brought several of the schools of QurÁanic legal scholarship to prominence above the others because of their stands on larger questions of Islamic orthodoxy. The dispersed local schools began to shape into something like political parties among the Sunni loyalists of the regime, and the number of positions winnowed down around the most successful legal schools.

Their initial position was not necessarily hard-line scripturalist. The first prominent school, organized at Baghdad in the middle generation of the 700s,

402 • I n t e l l e c t u a l C o m m u n i t i e s : We s t e r n Pa t h s

was the Hanifites, followers of Abu Hanifa, who took a relatively soft position of political compromise on questions of legitimate succession to the caliphate and a moderate line on predestination. The emerging MuÀtazilites tended to be allied with this legal school. In the next generation came a reaction led by Malik ibn Anas (at Muhammad’s city, Medina), founder of the Malikites, who took a vehemently literalist position against the rationalist theologians. But Malik’s own pupil al-ShafiÀi founded a more moderate lineage (the ShafiÀites); they softened the emphasis on QurÁanic literalism by sanctioning the use not only of the QurÁan but also of hadith, recollections of the Prophet’s companions, which could be used as a basis for interpretation. No doubt energized by this controversy, major work was done in al-ShafiÀi’s generation to establish a canonical collection of hadith (see 68 and 69 in Figure 8.1). In counterpoint came the fourth of the main legal schools, the Hanbalis (followers of Ibn Hanbal), who used hadith to reinforce traditionalist views, and who vehemently attacked the rational theologians.

Liberal and conservative impulses tended to alternate during these generations, with the conservatives coming later and in reaction to the liberal side. The turning point came with a showdown over the political power of the liberals. The ÀAbbasid caliphate had taken power by military force, and its legitimacy (like that of the preceding Umayyad caliphate) was disputed by various factions. The caliphs were casting about for religious legitimacy in various ways, at times offering alliance with the ShiÀites, and bringing them into their administration, at times supporting Sunni scripturalists, at other times patronizing the practitioners of kalam (Lapidus, 1988: 123–125; Massignon, 1982: 250–254). In the early 800s, the ÀAbbasids were at the height of their economic prosperity and military power. Turning away from the QurÁanic conservatives supported by his predecessor Harun al-Rashid, the powerful caliph al-MaÁmun moved to establish theocratic control by championing the doctrines of the MuÀtazilites. Among the central points was the doctrine that the QurÁan is created and not an eternal aspect of the divine essence. To enforce this policy would be to reduce the independence of the scriptural caretakers of the QurÁan and justify the intervention of the caliph in interpreting religious law.

Islamic historians refer to this episode as the “Inquisition.” The pejorative term results from the eventual failure and disgrace of this effort. Under caliph al-Rashid (r. 786–809) there had been a persecution from the other direction, on behalf of the emerging school of hadith and against kalam, during which the head of the Baghdad MuÀtazilites, Bishr al-MuÀtamir, had been imprisoned (Watt, 1985: 53; Hodgson, 1974: 1:388–389). In 827 caliph al-MaÁmun attempted to force religious scholars to accept the doctrine of the created QurÁan; al-MaÁmun died in 833, and his successors continued the policy intermittently

Tensions of Ideas: Islam, Judaism, Christendom • 403

for 20 years. Most of the Àulama gave in under political pressure from the caliphs; but opposition was tenaciously led by Ibn Hanbal, the most prominent hadith scholar, situated in the capital Baghdad itself. Ibn Hanbal became a hero of the conservatives by enduring imprisonment and threats of execution. Eventually in 847 caliph al-Mutawakkil capitulated to the political opposition and abandoned the effort to impose the MuÀtazilite theology. The triumphant Hanbalis in turn attempted to impose their own position. In future generations the Hanbalis became one of the leading legal schools, and the conservative anchor of the intellectual field, taking the leadership in attacking theological moderates as well as practitioners of philosophy.7

The defeat of the “Inquisition” was a turning point in the structure of Islamic religion and intellectual life generally. If the caliph had won, Islam would have been moved toward a more centralized and bureaucratic church, less centered on the local Àulama. Rational theology could have become institutionalized rather than marginalized. Intellectual structures would have more nearly parallelled those of the Christian Church, centered on rational theology rather than scripturalism and breeding its philosophical adjunct. Indigenous theologically based Islamic philosophy displayed its own creative dynamic through these early generations, developing atomic occasionalism, theories of free will and of causality, proofs of the existence and nature of God, theories of time and motion, distinctions among primary and secondary qualities. The period flashes with themes we associate with Zeno and Heraclitus, and again with the successors of Descartes. That is to say, Islamic philosophy at this point parallels developments in Greece and Europe prior to the dominance of Plato and Aristotle, and again after their overthrow. Creativity was not yet over, for it is fueled by conflict, and the shifting of external supports brought about a realignment of positions over the next few generations, and thus the innovative reorganization of intellectual space. But the center of gravity was pushed increasingly toward the conservative side. The MuÀtazilites did not disappear for several centuries,8 but they were frozen into a defensive posture from which creative energy had drained. Their decline opened a space in the intellectual field; and it was this vacuum that imports of Greek ideas now proceeded to fill. Importing is less creative than indigenous construction. What Eurocentric history regards as the only worthwhile topic constituted in its time a decline in the creativity of Islamic networks.

Importers of Foreign Philosophy

Just at the time when the MuÀtazilites were going into their political showdown and crisis, a concerted effort was made to import the “ancient learning” of Greek science and philosophy into the Islamic world. It was at this point—the

404 • I n t e l l e c t u a l C o m m u n i t i e s : We s t e r n Pa t h s

middle generation of the 800s—that a network of translators and commentators sprang up in Baghdad. Sporadic translations of Greek texts had appeared before this point; and there were long-standing schools of Christian and other non-Islamic scholars in various outlying places. But their work had produced neither novelty nor attention. In 830 Caliph al-MaÁmun—the same who attempted to impose an Inquisition on behalf of MuÀtazilite theology—estab- lished a “House of Wisdom” at the capital, a bureau of translation supporting many scholars.9 For the next three generations this network was active in translating Greek science, mathematics, logic, and philosophy.

It should be stressed that this group was tangential to Islamic intellectual life. Most of its members were non-Muslims: they were Nestorian Christians (an excommunicated sect which had left the Byzantine Empire for Persia around 430 c.e.); a few were Jacobites (a wing of the Monophysite heresy in Syria of the mid-500s), Sabians of the old Babylonian star worshippers, occasionally Zoroastrians.10 They did not take part in the controversies of the Àulama over theological-philosophical issues. Their niche at first was as carriers of practical skills, as court physicians, astrologers, and astronomers. Since teaching in these professions took place by personal apprenticeship, this group had some concern with the transmission of ideas and texts. Once a critical mass of such experts was assembled at Baghdad, it began the usual intellectual struggle for attention, in this case concentrated on their distinctive cultural capital, their access to textual traditions. Their claim to fame was not originality but possession of more texts, and eventually better translations.

The science, medicine, and mathematics thus introduced were religiously neutral. But they did establish an occupational base for intellectuals outside the career of Muslim religious scholar, primarily as court physician or court astrologer. Later we find that many of the prominent Muslim exponents of falsafa, from Rhazes and Ibn Sina down to Ibn Rushd (Averroës) and AbuÁlBarakat, were doctors. Philosophical creativity within these roles did not come about until the translation movement was over. During the early generations, idea imports were a substitute for creativity.

The main area in which this did not hold was in mathematics and astronomy. In the first generation of the House of Wisdom appeared al-Khwarizmi, from a Zoroastrian family. He coined the term al-jabr, translated by the Europeans as “algebra,” while “algorithm” was taken from his name; he laid out basic principles for solving equations of the first and second degree. A generation later the Sabian Thabit ibn Qurra developed versions of integral calculus, spherical trigonometry, and analytic and non-Euclidean geometry, and reformed Ptolemaic astronomy (DSB, 1981: 7:358–365; 13:288–292). Translations were made of Greek mathematics, from Euclid and Archimedes to Plutarch and Diophantus, along with the science of Aristotle and Galen. It is

Tensions of Ideas: Islam, Judaism, Christendom • 405

striking that the areas in which creativity occurred are not simply those in which prestigious Greek texts were introduced but rather areas in which there was a cross-connection of imports from India—apparently in the form not of textual translations but of practical knowledge. Thus, Thabit ibn Qurra began as a money changer in Harran (DSB, 1981: 13:288), and al-Khwarizmi, an Iranian from the Oxus delta, appears to have introduced the decimal system of Indian numerals (i.e., what Europeans call Arabic numerals). A single line of imports tends to stifle creativity; this is circumvented by multiple and heterogeneous sources of imports, which reinstate the creative competition and recombination of ideas.

This scientific creativity remained largely insulated from philosophy. But Greek cultural capital was now spilling over into the sphere of Arab intellectuals. The first to take advantage of it was al-Kindi, who happened to be closest to the scene, in his position as court overseer of the translators at Baghdad. The result of his labors was not very original; he popularized Greek learning in Arabic, writing an encyclopedic range of treatises across all the sciences, not omitting logic and philosophy. He had contacts with the Baghdad school of MuÀtazilites—then at the height of their political dominance—and he made an effort to accommodate Greek philosophy to Muslim theological issues. Titles of his books indicate he wrote on such MuÀtazilite themes as atoms, the essences of bodies, and the unity of God (Watt, 1973: 207–208). Al-Kindi’s own position was largely Neoplatonic, but modified to defend theologican doctrines of the creation of the world ex nihilo, the possibility of miracles and prophecy, and God’s eventual destruction of the world. Al-Kindi’s position was essentially eclectic, and was adopted neither by the theologians nor by the Greek-oriented falasifa. As the latter position came into its own after 900, it took a stronger stand, in opposition to theological particularism, in the form of Neoplatonism championed by al-Farabi. By this time al-Kindi’s importance had faded, and the period of translating Greek texts was largely over.

The Sufi Cult of Religious Experience

What became known as the Sufis (after suf, the wool cloak worn by wandering ascetics) began to appear in the 700s and 800s as an outcropping of ecstatic religious persons apart from the teachers at the official mosques. Some were wandering preachers; some were ultra-ritualists, making pilgrimages to holy places and saying prayers every step of the way; some were visionaries, who claimed a personal flash of divine contact or inspiration. There was at this time no emphasis on the practice of meditation or systematic methods for inducing visions. A frequent theme was asceticism, giving away one’s goods and wandering in poverty, along with practicing sexual celibacy; yet the Sufis did not

406 • I n t e l l e c t u a l C o m m u n i t i e s : We s t e r n Pa t h s

usually become organized into a monastic life, although there were later a few approaches to it, such as the spiritual community which al-Ghazali formed in Persia. In the early period, asceticism was widely displayed as a badge of religious commitment by members of various positions, including some of the famous MuÀtazilites. Later, when Sufism spread as a mass movement, it generally was organized as lay brotherhoods of persons who practiced ordinary trades but who met periodically for religious initiations and activities.

Sufism never broke organizationally from the conventional structures of Islamic society and religion; it provided supplementary communities in which men from all walks of life (and in rare instances women) could participate. The common theme of this rather inchoate Sufi movement was an emphasis on personal religious experience, away from the collective public rituals such as the five-times-daily prayers at the mosques and other public observances. The more radical Sufis carried this to an anti-ritualistic, anti-conventional extreme: the externals of the pilgrimage to Mecca were nothing, and one might break even the most sacred rules to demonstrate one’s inner commitment to a spiritual level transcending anything visible.

This tendency in Sufism took up the opposite side of the field from the scripturalists of the juridical schools and especially the collectors of hadith. It is not surprising to find the archconservative Ibn Hanbal polemicizing against al-Muhasibi (65 in Figure 8.1), who helped to crystallize Sufism from pious asceticism into full-blown mysticism. In the same generation (the mid-800s), we find at Baghdad the even more radical Sufi al-Bistami; influenced by an Indian teacher, he declared his identity with the Divine with the words: “Glory to me, how great is my glory!” Such radical expressions could be gotten away with, if just barely, during the period of upheaval in the struggle between MuÀtazilites and their opponents, with the defeat of the Inquisition. Even with such outrageousness, Sufism was becoming organized. As we see in Figure 8.1, the major Sufis were connected in lineages and centered on the main places of intellectual action, Basra and Baghdad; they were part of the division of the intellectual attention space. The leading figure at the end of the 800s, al-Junayd, drew on both Bistami and Muhasibi, and unified Sufism with an analytically argued theosophy. His pupil in turn was the famous al-Hallaj, who studied with all the Sufi networks, debated with the MuÀtazilites, and had personal contacts with Rhazes, the heretical philosopher.

Radical Sufis, as enemies of scripturalists, were capable of making alliances with all sorts of intellectual positions. Both a Neoplatonist like Ibn Sina and an antagonist of philosophy like al-Ghazali could have Sufi teachers and contacts; and we find Ibn Massara (1 in Figure 8.4), the first Muslim philosopher in Spain, setting up a school for both MuÀtazilite theology and Sufism. The fact is that Sufism had no hard kernel of doctrine one way or the other;

Tensions of Ideas: Islam, Judaism, Christendom • 407

it was simply an organized flux of religious energy sweeping around Islamic society on the loose organizational pathways of popular respect for religious piety, plus a politically generated distrust of the official expressions of religious ritual. How this vague religious experience was interpreted depended on the structures that divided the intellectual world at any particular time. Mystical experience, trans-intellectual though it may be, is always interpreted in terms of ideas, and these are produced by the historical networks of the intellectual community.

The radical al-Hallaj epitomizes a particular interpretation of Sufi mysticism (Massignon, 1982). It is a philosophical vision of the world capped by a divine reality beyond words and concepts; compared to this the world itself is unreal, and the individual experiencing this vision loses all sense of duality and becomes absorbed into the divine light and power. In 922 the outraged authorities responded to al-Hallaj’s claims with ritual vehemence, mutilating, torturing, crucifying, and burning his body, while from his cross al-Hallaj ecstatically called to the Baghdad crowd: “I am the truth!” For all the monstrousness of this drama, it is a product of the social structure of the intellectual field. Al-Hallaj did not depart from Islamic society into the periphery, experiencing his mystic union in remote solitude; he challenged Islamic religious power in its capital. His was not an inspired idiosyncracy; he was a direct pupil of the lineages of the most important Sufis. In Figure 8.1 we see the Sufi networks, which had been building up for five generations, brought together in al-Hallaj. And he was an intellectual cosmopolitan, with connections to all the important factions of his day. Even his doctrine of extreme person-centered pantheism was itself a version of Neoplatonism, just then emerging as the dominant position among the falasifa. Al-Hallaj’s extraordinary self-confidence, deliberately provoking martyrdom, was a boiling-over of emotional energy at a time when the intellectual community of Islam was maximally focused.

Realignment of Factions in the 900s

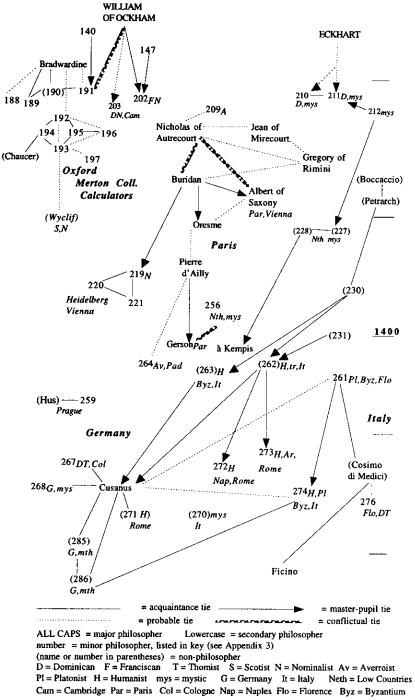

The early 900s were a time when all the structural tendencies of intellectual life came to a head. In Figures 8.1 and 8.2 we notice in this generation the first two really dominant figures in Islamic philosophy: al-Farabi and al-AshÀari; Saadia, the first major Jewish philosopher;11 plus a concentration of notable secondary figures, including Abu Bakhr al-Razi (Rhazes),12 the most important secular and anti-religious philosopher; the Sufi extremist al-Hallaj; plus notable logicians (Matta), developers of rational theology (al-Maturidi), and the last creative MuÀtazilite (Abu Hashim). This was also the generation in which occurred a crucial event for Islamic theological politics: the long-standing Imamite pretenders to the caliphate withdrew from active political opposition

408 • I n t e l l e c t u a l C o m m u n i t i e s : We s t e r n Pa t h s

by formulating the doctrine of the hidden Imam, with its implication that an inner faith would substitute, during the indefinite future, for political activism. If we separate the Jewish positions (since they would have been ignored by the Muslims, and in any case paralleled Muslim factions), we still find seven or eight distinctive stances struggling for attention in the intellectual field (see Figure 8.2). This strains the limits of the law of small numbers, and it is not surprising that only a few of these positions were successfully propagated to succeeding generations.

Most of these thinkers were at Baghdad. Basra had had its last gasp of activity; by the end of the century, its lineages had shifted to Nishapur, far to the east in Persia. Baghdad hung on for a few more generations, but hereafter its philosophers became increasingly embattled by anti-intellectual forces. Already by the end of the 900s, Persian cities such as Rayy (near modern Tehran) were becoming rival centers, and henceforth creativity was much more scattered, not only in Persia but also in central Asian Khwarazm and Afghanistan, as well as back to the Mediterranean coast, where Cairo, Damascus, and Aleppo acquired intermittent prominence. With this geographical dispersion, in later centuries the philosophical networks became less concentrated, their creativity more sparse.

Greek philosophy, falsafa, had by the early 900s largely passed the era of translations. The philosophers and logicians up to now had been almost entirely non-Muslim—Christians, together with some Sabians (Babylonian star worshippers) among the astronomer-mathematicians. Since translation ceased to be patronized by the court, the main social support of falsafa was the practice of medicine. In the Greek medicine of antiquity, the doctor was not merely a dispenser of cures but a public figure; arguing and lecturing was a major part of legitimating medicine at a time when its practice was not very effective. This style carried over into the Islamic context. Isaac Israeli, the first notable cosmopolitan Jewish philosopher, was a court physician at Tunis. His medical books, translated from Arabic into Hebrew and Latin, were more famous than his philosophy, and served as the medium by which his name as a philosopher became known. The same would happen to another doctor, Ibn Sina.

Galen’s and Aristotle’s logic was part of the medical apprenticeship and provided the terrain on which took place much of the innovations of the falasifa. Logic was treated broadly, as a means of classifying the disciplines of knowledge and expounding the modes of reality as well as of argument.13 The doctor Abu Bishr Matta, and his pupil al-Farabi, and in turn his pupil Yahia ibn ÀAdi (another doctor), led the logical developments of the “Baghdad school”; two generations later, Ibn Sina would construct the most comprehensive treatment of logic to date.

Tensions of Ideas: Islam, Judaism, Christendom • 409

FIGURE 8.2. ASHÀARITES, GREEK FALASIFA, AND THE SYNTHESES

OF IBN SINA AND AL-GHAZALI, 935–1100

410 • I n t e l l e c t u a l C o m m u n i t i e s : We s t e r n Pa t h s

Al-Farabi was one of the few Muslims in this group, and he made his mark by transmuting its cultural capital into Islamic terms. An independently wealthy individual living quietly without court patronage, he dedicated himself to gathering everything he could from the cosmopolitan network, seeking out the leading teachers and traveling as far as Byzantium. Al-Farabi represents the culmination of idea importing into Islam. He surveyed all the available Greek works and enumerated all the natural sciences, the main concern of the Baghdad translators, systematizing everything into a Neoplatonic hierarchy of emanations. Al-Farabi was most original in adapting Plato’s Republic to Islamic conditions: the Prophet, as head of Islam, is the true philosopher-king; just as the universe emanates from the absolute One, the successive ranks of political hierarchy emanate from the political head. Al-Farabi implies that after the Prophet, the headship is delegated to a being of secondary grade, whose qualities and powers are lessened. The vagueness of al-Farabi’s formulation is perhaps a deliberate appeal to cover all factions; the “second head” could be equally the caliph, the Àulama, or even the ShiÀite Imam. Al-Farabi’s hallmark is political caution and the avoidance of theological disputes. His Neoplatonism is a religion of reason, combining the naturalism of the sciences with the most abstract and general form of Islam that he could safely espouse.

Why would this religion of reason now rise to dominance in the network of philosophers? External political forces helped move the network in this direction. Islam, originally a religion of the Arabs, was pressuring its subject peoples to convert. Zoroastrians had already been persecuted and largely eliminated in the 800s. In 932–934, the caliph launched a persecution of Sabians, and the last of them in the scientific network (notably 105 and 127 in the key to Figure 8.2) converted to Islam. Christians came under increasing pressure, although we find them in the network of Yahia ibn ÀAdi’s successors down into the next century. The Muslim intellectuals who inhabited these circles had no reason to defend Christianity or any other religion; their structural location motivated them to take a studied neutrality. The freethinker Ibn al-Rawandi took the most dangerous stance, claiming the autonomy of science, superior to religion. Al-Farabi’s contemporary Rhazes even more explicitly rejected the clashing religious sects; he held that prophecy is superfluous to the light of reason, and indeed the cause of violence among religious rivals (Fakhry, 1983: 105). Rhazes, one of the first Muslims among the elite medical doctors, drew widely on the cosmopolitan communities intersecting at Baghdad, from India as well as Greece. Rhazes postulated a system of co-eternal principles, including atoms moving continually in the void, souls undergoing a cycle of rebirths, and a creator-God who sets in motion these preexistent materials. Rhazes’s eclectic synthesis was condemned on all sides; in his grandpupils’ generation it would be picked up by another heretical group, the secret Brethren of Purity.

Tensions of Ideas: Islam, Judaism, Christendom • 411

Al-Farabi’s philosophy was an attempt to be politically safe, avoiding the dynastic partisanship inherent in the various Sunni and ShiÀite theologies. In this respect he moved onto MuÀtazilite turf, an earlier attempt at a religion of reason and a neutral stance on dynastic issues. Increasingly powerful enemies were now accusing the MuÀtazilites of heterodoxy. This was the final generation in which anything creative would come from them in philosophy. Other practitioners of kalam, notably al-AshÀari and his followers, were retreating toward a more conservative position. The Neoplatonism of al-Farabi is the kind of structure-driven creativity which emerges to fill an emptying slot in the intellectual field as external political forces destroy their social bases. Al-Farabi, like al-Kindi before him, attracted no notice from his contemporaries in the networks of Muslim theology. This gave him a certain amount of safety; on occasion he fled Baghdad to avoid political troubles. As the Christians disappeared and MuÀtazilites faded out in the next few generations, al-Farabi’s philosophy was the one that survived and prospered. Later falasifa, as well as their critics, came to regard al-Farabi as preeminent.

The Crystallization of Rational Theology in a Conservative Direction

For Muslim intellectuals, the big news of the early 900s would have been the split which took place in the MuÀtazilite camp. Al-AshÀari, pupil of the head of the Basra school, al-JubaÁi, denounced the MuÀtazilites in 912 and announced his reconciliation with the hadith scripturalists. Al-AshÀari now admitted that the QurÁan is not created; using the distinction of essence and existence, he met objections by showing that any particular copy of the QurÁan is created, whereas its essence is eternal. There was some personal rivalry in this move, as the Basra headship was passed at just this time to al-JubaiÁs son, the acute metaphysician Abu Hashim. But the break was not merely personal, as we can see by the fact that MuÀtazilite creativity more or less dried up at this point, while the AshÀarite lineage prospered; its future generations would include the important thinkers al-Baqillani, al-Juwayni, al-Ghazali, and alSharastani (as we see in Figure 8.2). Moreover, among al-AshÀari’s contemporaries was al-Maturidi, in far-off Samarqand, who founded another lineage of theological moderates, somewhat closer to the MuÀtazilites on the issue of free will (Watt, 1973: 312–316). The theological factions were being revamped at this time across the board, on both the Sunni and ShiÀite sides.

If the AshÀarites were the most prominent lineage philosophically, it was because they had accumulated the intellectual capital of the MuÀtazilite debates.14 The AshÀarites firmly adopted time-atomism as their metaphysics. As we have seen, this doctrine emerged only gradually and with many disagreements in the MuÀtazilite camp; and in fact the strongest statement of timeatomism by a MuÀtazilite came from al-KaÀbi (109 in Figure 8.1), a contem-

412 • I n t e l l e c t u a l C o m m u n i t i e s : We s t e r n Pa t h s

porary of al-AshÀari. By the time of al-Baqillani, the AshÀarites were laying out time-atomism systematically as their own doctrine. The impression widespread in the West that Muslim theology is fatalistic, holding that an all-controlling God determines everything that happens in the world, is the result of the orthodox stamp which the AshÀarites put on this MuÀtazilite doctrine.

The MuÀtazilite-AshÀarite network, for all the concessions the latter made to scripturalism, took indigenous Muslim philosophy toward issues comparable at many points to positions later argued by the famous philosophers of medieval Christendom and early modern Europe. Let us note the following:

1.Al-AshÀari rejected the MuÀtazilites’ extreme emphasis on the unity of God in order to agree with the traditionalists’ view that God has positive attributes (power, knowledge, life, and so on as described in the QurÁan). These cannot be considered identical with God’s essence; but they are eternal, and subsist in God’s essence (Fakhry, 1983: 53, 58–59, 204–205, 214–215). This line of argument had already become acute with AshÀari’s MuÀtazilite teacher al-JubaÁi, and his son Abu Hashim. The latter worked out subtle distinctions of state and attribute, moving along a path similar to that of Duns Scotus in the Christian network four centuries later. Abu Hashim took the discussion of bodies and their accidents to its most extreme step, holding that a body can be stripped of all accidents except being. Other MuÀtazilites had argued about which attributes were most primordial; al-KaÀbi, the strongest advocate of time-atomism, held that bodies can be divested of all attributes except color, while the AshÀarites distinguished between primary and secondary accidents, the former of which necessarily accompany substance, and include motion, rest, and location. The argument looks something like Locke’s primary and secondary qualities, although the AshÀarites went on to include among primary accidents features such as taste and smell, dampness and dryness, heat and cold. The primary-secondary distinction was not worked out with the radicalness of Locke because the level of abstraction upheld by the intellectual network did not remain very high.

2.The AshÀarites held that God’s decrees are fiat, independent of and superior to any rational or moral conditions. Al-Baqillani argued that if God desired, he could have created an entirely different world, or refrained from creating the world at all. Here we have a position like that which was taken by Duns Scotus and the Ockhamists, emphasizing the unlimited and miraculous power of God’s will. The condemnation of Averroist determinism by the Paris authorities in 1277, which led to this conception of the unlimited power of God, is structurally paralleled by the political condemnation of the MuÀtazilites’ rational restrictions on God as following from his unity and justice. In both cases a philosophy is constructed which extends the implications of the opposite position.

Tensions of Ideas: Islam, Judaism, Christendom • 413

3.The mature MuÀtazilite and AshÀarite time-atomism foreshadows the occasionalist system of Malebranche. In the latter’s system there is a psychophysical parallelism in which bodies are moved not by the human will but by God. Malebranche, a priest arguing against the mechanistic worldviews of the 1600s, was doubtless not imitating the Muslims; it is simply that in both cases, the type of argument serves to make God omnipresent even within a world which philosophical argument has concluded consists of material substances.

4.By the late 900s, the AshÀarites denied that there are unchanging essences and eternal laws (Wolfson, 1976: 543–544; Fakhry, 1983: 210–212). Moving to the opposite pole from the Neoplatonists, now on the scene among the falasifa, they held that facts are concrete and particular. Al-Baqillani’s version of atomic instants held that every particular event is produced by the will of God; God may make a sequence of repetitive events, but there are no natural laws, no necessity of repetition. Here the argument foreshadows Hume’s denial of causality, and paves the way for al-Ghazali’s anti-causal argument in the AshÀarite lineage three generations later. Al-Baqillani also held that bodies in themselves can have any sort of qualities; that they have one particular form rather than another requires a determinant, which implies the existence of God. This also makes explicit the notion of contingency, which was to be stressed by Ibn Sina and by al-Juwayni.

5.The MuÀtazilites and AshÀarites worked out a series of proofs of theological positions: for the existence of God; for God’s unity; for the creation of the world ex nihilo; against the Aristotelean preexistence of matter and eternity of the world. Abu-Àl-Hudhayl, in the early 800s generation, produced an argument for the creation of the world that was to be characteristic of kalam: all accidents are generated; all bodies have accidents (including the accident of being composite); hence the world as a body must be generated (Davidson, 1987: 134–136). About the same time al-Nazzam held that an infinite cannot be traversed, and that one infinite cannot be greater than another infinite; these points imply the finiteness of the world in time (Wolfson, 1976: 416–417). Saadia summarized related MuÀtazilite arguments for creation, such as the argument that if past time were infinite, then the original cause of existence could never reach me; since I exist, there must be a temporal beginning (Hyman and Walsh, 1983: 348). The procedure of kalam was to prove the creation first, then use this as basis for the proof of a creator. The Jewish academies came alive in this period through factional arguments between Karaites and Rabbanites, paralleling kalam and hadith; they were similarly concerned with reasoned critique or defense of anthropomorphic images in holy scripture. Such proofs became one of the staples of Jewish philosophy leading up to Maimonides.15

These issues, more than anything else, propelled Islamic philosophy in the

414 • I n t e l l e c t u a l C o m m u n i t i e s : We s t e r n Pa t h s

direction of explicit proofs and conceptual analysis. More subtle arguments were added in the next centuries, especially in the AshÀarite lineage (al-Baqil- lani, al-Juwayni, al-Ghazali); for instance, the proof that if an object (the world) has particular characteristics but could have had others, there must be something (God) which caused it to be particularized (Davidson, 1987: 174– 178). This line of argument, foreshadowing Leibniz’s principle of sufficient reason, was developed by al-Juwayni in the mid-1000s. Further subtleties arose as the creationists debated Aristoteleans over the eternity of the world. AlFarabi, Ibn Sina, and later Ibn Rushd (Averroës) responded to kalam by distinguishing among different types of infinities and infinite regresses (Davidson, 1987: 127–143). Ibn Sina broke ground beyond these cosmological proofs by arguing on the basis of analysis of the concepts of necessary and possible being.16 By the time of al-Ghazali (al-Juwayni’s pupil), it had become possible to point out that even a proof of the existence of a creator or first cause does not prove its unity or incorporeality, and that philosophy comes up against epistemological limits beyond which it must cede to religious authority.

6. The payoff of this accumulation of arguments is not only in the philosophies of Ibn Sina and al-Ghazali; it is also already found in al-Baqillani, the first systematizer of the AshÀarite position. In order to undergird his timeatomism and his proofs of God and creation, al-Baqillani set forth a theory of knowledge. He divided knowledge into God’s eternal knowledge and creatures’ knowledge, and the latter into what is known through the senses, through discourse, or authoritatively through history or revelation. Among necessary knowledge he included knowledge of one’s own existence; here we have the “cogito ergo sum,” but al-Baqillani did not separate its indubitability from that of other sensory knowledge. Al-Baqillani’s epistemology is uncritical and not very sophisticated. But the emergence of epistemology is itself a breakthrough. Further AshÀarite systematizers in this lineage, such as al-Baghdadi (167 in Figure 8.2) and al-Juwayni, also now based their expositions on an epistemology. The major conceptual ingredients for more abstract and critical philosophy were in place, on which was built the creativity of Ibn Sina and al-Ghazali.

The ShiÀite Alliance and the United Front of Heterodoxies

The 900s mark a turning point in the intellectual and political history of Islam and in their connecting link, religious politics. Religious factions lined up for a power showdown. The large number of Sunni legal schools had winnowed down to a few main schools of law; the earlier struggle between hadith and QurÁan as scriptural basis was now resolved by inclusion. On the ShiÀite side, the old factional opposition, once fragmented among many contenders, became

Tensions of Ideas: Islam, Judaism, Christendom • 415

unified as well. The ShiÀites posed a danger not only of military uprisings on the periphery but also in the core of the empire; in Baghdad itself, the ShiÀites made up 30 percent of the population (Massignon, 1982: 240, 252). In the early 800s, Caliph al-MaÁmun had attempted to negotiate a settlement by offering the succession to the current ShiÀite pretender; the failure of this move led to the ill-fated Inquisition, an attempt to assert caliphal autonomy from theological factions (Lapidus, 1988: 124). Now, in the early 900s, the caliph’s regime was full of ShiÀite administrators, especially in finances and tax collection, though reserving the executive branch for Sunnites; his personal staff was drawn from MuÀtazilites. There was constant concern for ShiÀite rebellions in the provinces and conspiracies at court. In this context, al-Nawbakhti (100 in Figure 8.1), a wealthy Baghdad businessman involved in court finances, formulated the doctrine of the Hidden Imam. The Imam was the alleged successor to the Prophet, on the side which lost the earliest civil war. Al-Nawbakhti now held that the twelfth Imam was in hiding, and would reappear at some time in the future to establish the reign of justice. This also meant giving up concrete claim to the succession and transforming the Imam into a transcendental symbol, depicted as a luminous divine substance transmitted to a human intermediary in each generation. A colleague of al-Nawbakhti (102 in Figure 8.2) put the ShiÀites on a comparable basis with the Sunnites by formulating their own canonical Imamite law and hadith.

For a time the ShiÀite front won political support. The caliphate, which had been gradually losing de facto power in the provinces since the mid-800s, was subordinated in 945 by a Buwayid sultan. The Buwayids encouraged Imamism, as the doctrine no longer threatened rebellion in favor of an heir to the line of Ali, while it delegitimated the caliphate and was indifferent to secular rule. The chief remaining ShiÀite faction, the IsmaÀilis, established a rival caliphate in Tunisia in the early 900s, and conquered Egypt and Syria from the crumbling Baghdad caliphate in 970. No ShiÀite orthodoxy could be imposed, however. The empire continued to disintegrate, and the Sunnites shifted to other power bases outside the crumbling capital—new conquering states from the east, as well as the Sufi missionary movements spreading from within.