Baumol & Blinder MACROECONOMICS (11th ed)

.pdf

LICENSED TO:

CHAPTER 9 Demand-Side Equilibrium: Unemployment or Inflation? 197

| SUMMARY |

1. Because imports rise as GDP rises, while exports are |

2. If imports depend on GDP, international trade reduces |

insensitive to (domestic) GDP, net exports decline as |

the value of the multiplier. |

GDP rises. |

|

| TEST YOURSELF |

1. Suppose exports and imports of a country are given by |

shown in the following table, construct a 45° line dia- |

the following: |

gram and locate the equilibrium level of GDP. |

|

GDP |

Exports |

Imports |

|

|

$2,500 |

$400 |

$250 |

|

|

3,000 |

400 |

300 |

|

|

3,500 |

400 |

350 |

|

|

4,000 |

400 |

400 |

|

|

4,500 |

400 |

450 |

|

5,000 |

400 |

500 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Domestic |

|

|

GDP |

Expenditures |

|

|

|

|

|

|

$2,500 |

$3,100 |

|

|

3,000 |

3,400 |

|

|

3,500 |

3,700 |

|

|

4,000 |

4,000 |

|

|

4,500 |

4,300 |

|

5,000 |

4,600 |

|

|

Calculate net exports at each level of GDP. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

2. If domestic expenditure (the sum of C 1 I 1 G in the |

3. Now raise exports to $650 and find the equilibrium |

||

economy described in Test Yourself Question 1) is as |

again. How large is the multiplier? |

||

| DISCUSSION QUESTION |

1.Explain the logic behind the finding that variable imports reduce the numerical value of the multiplier.

Copyright 2009 Cengage Learning, Inc. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part.

Copyright 2009 Cengage Learning, Inc. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part.

LICENSED TO:

BRINGING IN THE SUPPLY SIDE:

UNEMPLOYMENT AND INFLATION?

We might as well reasonably dispute whether it is the upper or the under blade of a pair of scissors that cuts a piece of paper, as whether value is governed by [demand] or [supply].

ALFRED MARSHALL

T he previous chapter taught us that the position of the economy’s total expenditure (C 1 I 1 G 1 (X 2 IM)) schedule governs whether the economy will experience a recessionary or an inflationary gap. Too little spending leads to a recessionary gap. Too much leads to an inflationary gap. Which sort of gap actually occurs is of considerable practical importance, because a recessionary gap translates into unemployment whereas

an inflationary gap leads to inflation.

But the tools provided in Chapter 9 cannot tell us which sort of gap will arise because, as we learned, the position of the expenditure schedule depends on the price level—and the price level is determined by both aggregate demand and aggregate supply. So this chapter has a clear task: to bring the supply side of the economy back into the picture.

Doing so will put us in a position to deal with the crucial question raised in earlier chapters: Does the economy have an efficient self-correcting mechanism? We shall see that the answer is “yes, but”: Yes, but it works slowly. The chapter will also enable us to explain the vexing problem of stagflation—the simultaneous occurrence of high unemployment and high inflation—which plagued the economy in the 1980s and which some people worry may stage a comeback.

C O N T E N T S

PUZZLE: WHAT CAUSES STAGFLATION? |

ADJUSTING TO A RECESSIONIONARY GAP: |

STAGFLATION FROM A SUPPLY SHOCK |

|

THE AGGREGATE SUPPLY CURVE |

DEFLATION OR UNEMPLOYMENT? |

APPLYING THE MODEL TO A GROWING |

|

Why Nominal Wages and Prices Won’t Fall (Easily) |

|||

Why the Aggregate Supply Curve Slopes Upward |

ECONOMY |

||

Does the Economy Have a Self-Correcting |

|||

Shifts of the Aggregate Supply Curve |

Demand-Side Fluctuations |

||

Mechanism? |

|||

|

Supply-Side Fluctuations |

||

EQUILIBRIUM OF AGGREGATE DEMAND |

An Example from Recent History: Deflation in Japan |

||

PUZZLE RESOLVED: EXPLAINING STAGFLATION |

|||

AND SUPPLY |

ADUSTING TO AN INFLATIONARY GAP: |

||

|

A ROLE FOR STABILIZATION POLICY |

||

INFLATION AND THE MULTIPLIER |

INFLATION |

||

RECESSIONARY AND INFLATIONARY |

Demand Inflation and Stagflation |

|

|

|

|

||

GAPS REVISITED |

A U.S. Example |

|

Copyright 2009 Cengage Learning, Inc. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part.

LICENSED TO: |

|

|

|

|

200 |

PART 2 The Macroeconomy: Aggregate Supply and Demand |

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

PUZZLE: |

|

WHAT CAUSES STAGFLATION? |

|

|

|

|

|

The financial press in 2007 and 2008 was full of stories about the possible return of the dreaded disease of stagflation, which plagued the U.S. economy in the 1970s and early 1980s. Many economists, however, found this talk unduly alarming.

On the surface, the very existence of stagflation—the combination of economic stagnation and inflation—seems to contradict one of our Ideas for Beyond the Final Exam from Chapter 1: that there is a trade-off between inflation and un-

employment. Low unemployment is supposed to make the inflation rate rise, and high unemployment is supposed to make inflation fall. (This trade-off will be discussed in more detail in Chapter 16.) Yet things do not always work out this way. For example, both unemployment and inflation rose together in the early 1980s and then fell together in the late 1990s. Why is that? What determines whether inflation and unemployment move in opposite directions (as in the trade-off view) or in the same direction (as during a stagflation). This chapter will provide some answers.

THE AGGREGATE SUPPLY CURVE

The aggregate supply curve shows, for each possible price level, the quantity of goods and services that all the nation’s businesses are willing to produce during a specified period of time, holding all other determinants of aggregate quantity supplied constant.

In earlier chapters, we noted that aggregate demand is a schedule, not a fixed number. The quantity of real gross domestic product (GDP) that will be demanded depends on the price level, as summarized in the economy’s aggregate demand curve. The same point applies to aggregate supply: The concept of aggregate supply does not refer to a fixed number, but rather to a schedule (an aggregate supply curve).

The volume of goods and services that profit-seeking enterprises will provide depends on the prices they obtain for their outputs, on wages and other production costs, on the capital stock, on the state of technology, and on other things. The relationship between the price level and the quantity of real GDP supplied, holding all other determinants of quantity supplied constant, is called the economy’s aggregate supply curve.

Figure 1 shows a typical aggregate supply curve. It slopes upward, meaning that as prices rise, more output is produced, other things held constant. Let’s see why.

Why the Aggregate Supply Curve Slopes Upward

Producers are motivated mainly by profit. The profit made by producing an additional unit of output is simply the difference between the price at which it is sold and the unit cost of production:

FIGURE 1

An Aggregate Supply

Curve

S |

Price Level |

S |

Real GDP |

Unit profit 5 Price 2 Unit cost

The response of output to a rising price level—which is what the slope of the aggregate supply curve shows—depends on the response of costs. So the question is: Do costs rise along with selling prices, or not?

The answer is: Some do, and some do not. Many of the prices that firms pay for labor and other inputs remain fixed for periods of time—although certainly not forever. For example, workers and firms often enter into long-term labor contracts that set nominal wages a year or more in advance. Even where no explicit contracts exist, wage rates typically adjust only annually. Similarly, a variety of material inputs are delivered to firms under long-term contracts at prearranged prices.

This fact is significant because firms decide how much to produce by comparing their selling prices with their costs of production. If the selling prices of the firm’s products rise

Copyright 2009 Cengage Learning, Inc. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part.

LICENSED TO:

CHAPTER 10 |

Bringing in the Supply Side: Unemployment and Inflation? |

201 |

while its nominal wages and other factor costs are fixed, production becomes more profitable, and firms will presumably produce more.

A simple example will illustrate the idea. Suppose that, given the scale of its operations, a particular firm needs one hour of labor to manufacture one additional gadget. If the gadget sells for $9, workers earn $8 per hour, and the firm has no other costs, its profit on this unit will be

Unit profit 5 Price 2 Unit cost

5 $9 2 $8 5 $1

If the price of the gadget then rises to $10, but wage rates remain constant, the firm’s profit on the unit becomes

Unit profit 5 Price 2 Unit cost

5 $10 2 $8 5 $2

With production more profitable, the firm presumably will supply more gadgets.

The same process operates in reverse. If selling prices fall while input costs remain relatively fixed, profit margins will be squeezed and production cut back. This behavior is summarized by the upward slope of the aggregate supply curve: Production rises when the price level (henceforth, P) rises, and falls when P falls. In other words,

The aggregate supply curve slopes upward because firms normally can purchase labor and other inputs at prices that are fixed for some period of time. Thus, higher selling prices for output make production more attractive.1

The phrase “for some period of time” alerts us to the important fact that the aggregate supply curve may not stand still for long. If wages or prices of other inputs change, as they surely will during inflationary times, then the aggregate supply curve will shift.

Shifts of the Aggregate Supply Curve

So let’s consider what happens when input prices change.

The Nominal Wage Rate The most obvious determinant of the position of the aggregate supply curve is the nominal wage rate (sometimes called the “money wage rate”). Wages are the major element of cost in the economy, accounting for more than 70 percent of all inputs. Because higher wage rates mean higher costs, they spell lower profits at any given selling prices. That relationship explains why companies have sometimes been known to dig in their heels when workers demand increases in wages and benefits. For example, negotiations between General Motors and the United Auto Workers led to a brief strike in September 2007 because GM felt it had to reduce its labor costs in order to survive.

Returning to our example, consider what would happen to a gadget producer if the nominal wage rate rose to $8.75 per hour while the gadget’s price remained $9. Unit profit would decline from $1 to

$9.00 2 $8.75 5 $0.25

With profits thus squeezed, the firm would probably cut back on production.

Thus, a wage increase leads to a decrease in aggregate quantity supplied at current prices. Graphically, the aggregate supply curve shifts to the left (or inward) when nominal wages rise, as shown in Figure 2 on the next page. In this diagram, firms are willing to supply $6,000 billion in goods and services at a price level of 100 when wages are low (point A). But after wages increase, the same firms are willing to supply only $5,500 billion at this

1 There are both differences and similarities between the aggregate supply curve and the microeconomic supply curves studied in Chapter 4. Both are based on the idea that quantity supplied depends on how output prices move relative to input prices. But the aggregate supply curve pertains to the behavior of the overall price level, whereas a microeconomic supply curve pertains to the price of some particular commodity.

Copyright 2009 Cengage Learning, Inc. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part.

LICENSED TO:

202 |

PART 2 |

The Macroeconomy: Aggregate Supply and Demand |

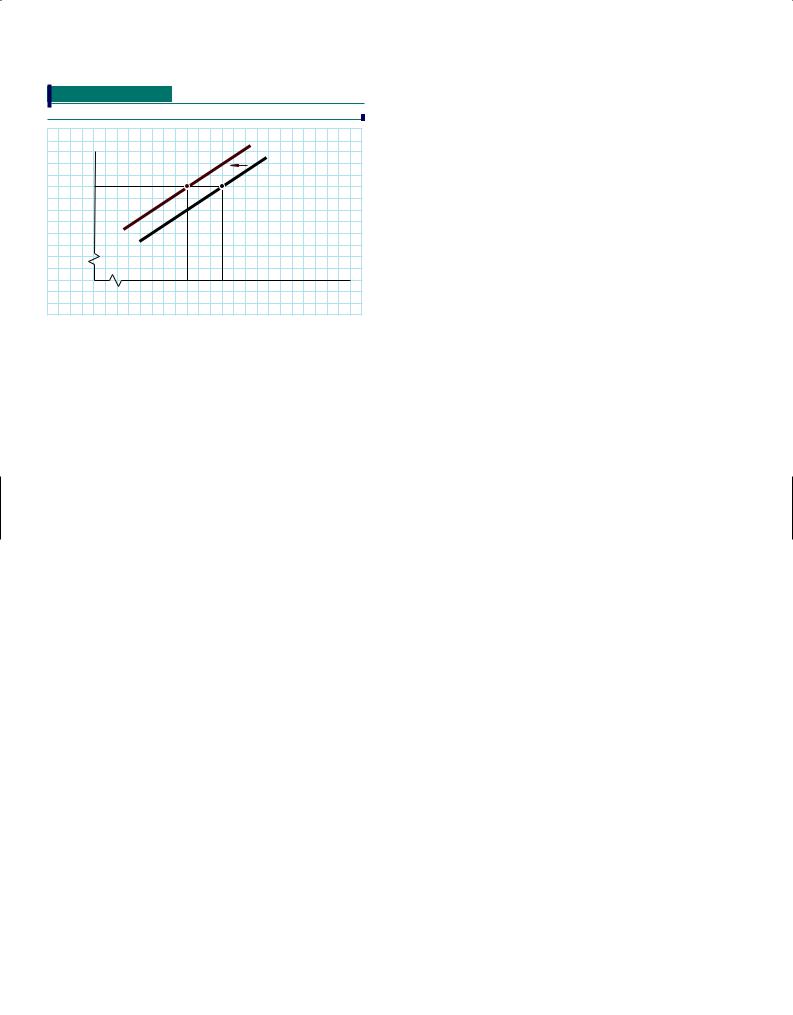

FIGURE 2

A Shift of the Aggregate Supply Curve

price level (point B). By similar reasoning, the aggregate supply curve will shift to the right (or outward) if wages fall.

S1 (higher wages)

S0 (lower wages)

|

B |

A |

(P ) |

100 |

|

|

|

|

Level |

S1 |

|

Price |

|

|

S0 |

|

|

|

|

5,500 6,000

Real GDP (Y )

NOTE: Amounts are in billions of dollars per year.

quantity supplied—from A to

An increase in the nominal wage shifts the aggregate supply curve inward, meaning that the quantity supplied at any price level declines. A decrease in the nominal wage shifts the aggregate supply curve outward, meaning that the quantity supplied at any price level increases.

The logic behind these shifts is straightforward. Consider a wage increase, as indicated by the brickcolored line in Figure 2. With selling prices fixed at 100 in the illustration, an increase in the nominal wage means that wages rise relative to prices. In other words, the real wage rate rises. It is this increase in the firms’ real production costs that induces a contraction of

B in the diagram.

Productivity is the amount of output produced by a unit of input.

Prices of Other Inputs In this regard, wages are not unique. An increase in the price of any input that firms buy will shift the aggregate supply curve in the same way. That is,

The aggregate supply curve is shifted to the left (or inward) by an increase in the price of any input to the production process, and it is shifted to the right (or outward) by any decrease.

The logic is exactly the same.

Although producers use many inputs other than labor, the one that has attracted the most attention in recent decades is energy. Increases in the prices of imported energy, such as those that took place over most of the period from 2002 until this book went to press, push the aggregate supply curve inward—as shown in Figure 2. By the same token, decreases in the price of imported oil, such as the ones we enjoyed briefly in the second half of 2006, shift the aggregate supply curve in the opposite direction—outward.

Technology and Productivity Another factor that can shift the aggregate supply curve is the state of technology. The idea that technological progress increases the productivity of labor is familiar from earlier chapters. Holding wages constant, any increase of productivity will decrease business costs, improve profitability, and encourage more production.

Once again, our gadget example will help us understand how this process works. Suppose the price of a gadget stays at $9 and the hourly wage rate stays at $8, but gadget workers become more productive. Specifically, suppose the labor input required to manufacture a gadget decreases from one hour (which costs $8) to three-quarters of an hour (which costs just $6). Then unit profit rises from $1 to

$9 2 (3⁄4) $8 5 $9 2 $6 5 $3

The lure of higher profits should induce gadget manufacturers to increase output— which is, of course, why companies constantly strive to raise their productivity. In brief, we have concluded that

Improvements in productivity shift the aggregate supply curve outward.

We can therefore interpret Figure 2 as illustrating the effect of a decline in productivity. As we mentioned in Chapter 7, a slowdown in productivity growth was a persistent problem for the United States for more than two decades starting in 1973.

Available Supplies of Labor and Capital The last determinants of the position of the aggregate supply curve are the ones we studied in Chapter 7: The bigger the

Copyright 2009 Cengage Learning, Inc. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part.

LICENSED TO:

CHAPTER 10 |

Bringing in the Supply Side: Unemployment and Inflation? |

203 |

economy—as measured by its available supplies of labor and capital—the more it is capable of producing. Thus:

As the labor force grows or improves in quality, and as investment increases the capital stock, the aggregate supply curve shifts outward to the right, meaning that more output can be produced at any given price level.

So, for example, the great investment boom of the late 1990s, by boosting the supply of capital, left the U.S. economy with a greater capacity to produce goods and services—that is, it shifted the aggregate supply curve outward.

These factors, then, are the major “other things” that we hold constant when drawing an aggregate supply curve: nominal wage rates, prices of other inputs (such as energy), technology, labor force, and capital stock. A change in the price level moves the economy along a given supply curve, but a change in any of these determinants of aggregate quantity supplied shifts the entire supply schedule.

EQUILIBRIUM OF AGGREGATE DEMAND AND SUPPLY |

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

Chapter 9 taught us that the price level is a crucial deter- |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

minant of whether equilibrium GDP falls below full |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

employment (a “recessionary gap”), precisely at full em- |

|

|

D |

|

|

|

|

S |

||

ployment, or above full employment (an “inflationary |

) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

(P |

130 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||

gap”). We can now analyze which type of gap, if any, will |

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||

Level |

120 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||

occur in any particular case by combining the aggregate |

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||

110 |

|

|

|

E |

|

|

||||

supply analysis we just completed with the aggregate de- |

100 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||

Price |

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||

mand analysis from the last chapter. |

|

90 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

80 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||

Figure 3 displays the simple mechanics. In the figure, the |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||

aggregate demand curve DD and the aggregate supply |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

D |

||

|

|

S |

|

|

|

|

|

|||

curve SS intersect at point E, where real GDP (Y) is $6,000 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||

billion and the price level (P) is 100. As can be seen in the |

|

|

5,200 |

5,600 |

6,000 |

6,400 |

6,800 |

|||

graph, at any higher price level, such as 120, aggregate |

|

|

||||||||

|

|

|

Real GDP (Y ) |

|

||||||

quantity supplied would exceed aggregate quantity de- |

|

|

|

|

||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||

manded. In such a case, there would be a glut of goods on |

NOTE: Amounts are in billions of dollars per year. |

FIGURE 3 |

||||||||

the market as firms found themselves unable to sell all their |

||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||

output. As inventories piled up, firms would compete more vigorously for the available |

|

Equilibrium of Real |

||||||||

customers, thereby forcing prices down. Both the price level and production would fall. |

|

GDP and the |

||||||||

|

Price Level |

|||||||||

At any price level lower than 100, such as 80, |

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

quantity demanded would exceed quantity |

TABLE 1 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

supplied. There would be a shortage of goods |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||

Determination of the Equilibrium Price Level |

|

|

|

|

||||||

on the market. With inventories disappearing |

|

|

|

|

||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

and customers knocking on their doors, firms |

(1) |

(2) |

|

(3) |

(4) |

|

|

|

(5) |

|

would be encouraged to raise prices. The price |

|

Aggregate |

Aggregate |

Balance of |

|

|

|

|||

level would rise, and so would output. Only |

|

Quantity |

|

Quantity |

Supply and |

|

|

Prices |

||

when the price level is 100 are the quantities of |

Price Level |

Demanded |

Supplied |

Demand |

|

|

will be: |

|||

real GDP demanded and supplied equal. |

80 |

$6,400 |

$5,600 |

Demand |

|

|

Rising |

|||

Therefore, only the combination of P 5 100 and |

|

|

|

|

exceeds supply |

|

||||

Y 5 $6,000 is an equilibrium. |

90 |

6,200 |

5,800 |

Demand |

|

|

Rising |

|||

Table 1 illustrates this conclusion by using a |

|

|

|

|

exceeds supply |

|

||||

100 |

6,000 |

6,000 |

Demand |

|

|

Unchanged |

||||

tabular analysis similar to the one in the previ- |

|

|

||||||||

|

|

|

|

equals supply |

|

|

||||

ous chapter. Columns (1) and (2) constitute an |

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||

110 |

5,800 |

6,200 |

Supply |

|

|

|

Falling |

|||

aggregate demand schedule corresponding to |

|

|

|

|

exceeds demand |

|

||||

curve DD in Figure 3. Columns (1) and (3) con- |

120 |

5,600 |

6,400 |

Supply |

|

|

|

Falling |

||

stitute an aggregate supply schedule corre- |

|

|

|

|

exceeds demand |

|

||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

sponding to aggregate supply curve SS. |

NOTE: Quantities are in billions of dollars. |

|

|

|

|

|

||||

Copyright 2009 Cengage Learning, Inc. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part.

LICENSED TO:

204 |

PART 2 |

The Macroeconomy: Aggregate Supply and Demand |

The table clearly shows that equilibrium occurs only at P 5 100. At any other price level, aggregate quantities supplied and demanded would be unequal, with consequent upward or downward pressure on prices. For example, at a price level of 90, customers demand $6,200 billion worth of goods and services, but firms wish to provide only $5,800 billion. In this case, the price level is too low and will be forced upward. Conversely, at a price level of 110, quantity supplied ($6,200 billion) exceeds quantity demanded ($5,800 billion), implying that the price level must fall.

INFLATION AND THE MULTIPLIER

To illustrate the importance of the slope of the aggregate supply curve, we return to a question we posed in the last chapter: What happens to equilibrium GDP if the aggregate demand curve shifts outward? We saw in Chapter 9 that such changes have a multiplier effect, and we noted that the actual numerical value of the multiplier is considerably smaller than suggested by the oversimplified multiplier formula. One of the reasons, variable imports, emerged in an appendix to that chapter. We are now in a position to understand a second reason:

Inflation reduces the size of the multiplier.

The basic idea is simple. In Chapter 9, we described a multiplier process in which one person’s spending becomes another person’s income, which leads to further spending by the second person, and so on. But this story was confined to the demand side of the economy; it ignored what is likely to be happening on the supply side. The question is: As the multiplier process unfolds, will firms meet the additional demand without raising prices?

If the aggregate supply curve slopes upward, the answer is no. More goods will be provided only at higher prices. Thus, as the multiplier chain progresses, pulling income and employment up, prices will rise, too. This development, as we know from earlier chapters, will reduce net exports and dampen consumer spending because rising prices erode the purchasing power of consumers’ wealth. As a consequence, the multiplier chain will not proceed as far as it would have in the absence of inflation.

How much inflation results from a given rise in aggregate demand? How much is the multiplier chain muted by inflation? The answers to these questions depend on the slope of the economy’s aggregate supply curve.

For a concrete example, let us return to the $200 billion increase in investment spending used in Chapter 9. There we found (see especially Figure 10 on page 186) that $200 billion in additional investment spending would eventually lead to $800 billion in additional spending if the price level did not rise—that is, it tacitly assumed that the aggregate supply curve was horizontal. But that is not so. The slope of the aggregate supply curve tells us how any expansion of aggregate demand gets apportioned between higher output and higher prices.

In our example, Figure 4 shows the $800-billion rightward shift of the aggregate demand curve, from D0D0 to D1D1, that we derived from the oversimplified multiplier formula in Chapter 9. We see that, as the economy’s equilibrium moves from point E0 to point E1, real GDP does not rise by $800 billion. Instead, prices rise, cancelling out part of the increase in quantity demanded. As a result, output rises from $6,000 billion to $6,400 billion—an increase of only $400 billion. Thus, in the example, inflation reduces the multiplier from $800/$200 5 4 to $400/$200 5 2. In general:

As long as the aggregate supply curve slopes upward, any increase in aggregate demand will push up the price level. Higher prices, in turn, will drain off some of the higher real demand by eroding the purchasing power of consumer wealth and by reducing net exports. Thus, inflation reduces the value of the multiplier below what is suggested by the oversimplified formula.

Copyright 2009 Cengage Learning, Inc. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part.

LICENSED TO:

CHAPTER 10 |

Bringing in the Supply Side: Unemployment and Inflation? |

205 |

||

Notice also that the price level in this example has been |

|

|

||

FIGURE 4 |

|

|

||

pushed up (from 100 to 120, or by 20 percent) by the rise |

|

|

|

|

|

Inflation and the Multiplier |

|

||

in investment demand. This, too, is a general result: |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

As long as the aggregate supply curve slopes upward, any outward shift of the aggregate demand curve will increase the price level.

The economic behavior behind these results is certainly |

|

|

D1 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

not surprising. Firms faced with large increases in quan- |

) |

|

|

|

S |

|

D0 |

|

|

||

tity demanded at their original prices respond to these |

(P |

|

|

|

|

|

$800 |

|

|

||

Level |

130 |

|

|

||

changed circumstances in two natural ways: They raise |

billion |

|

|

||

120 |

E1 |

|

|||

production (so that real GDP rises), and they raise prices |

Price |

110 |

E |

|

|

(so the price level rises). But this rise in the price level, in |

|

|

|||

100 |

|

|

|

||

turn, reduces the purchasing power of the bank accounts |

|

90 |

|

|

|

|

80 |

|

|

D1 |

|

and bonds held by consumers, and they, too, react in the |

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

natural way: They reduce their spending. Such a reaction |

|

|

S |

|

D0 |

amounts to a movement along aggregate demand curve |

|

|

|

|

|

D1D1 in Figure 4 from point A to point E1. |

|

|

6,000 |

6,400 |

6,800 |

Figure 4 also shows us exactly where the oversimpli- |

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|

|

|

fied multiplier formula goes wrong. By ignoring the ef- |

|

|

Real GDP (Y ) |

|

|

fects of the higher price level, the oversimplified formula |

|

|

|

|

|

erroneously pretends that the economy moves horizon- |

NOTE: Amounts are in billions of dollars per year. |

|

|

||

|

|

|

|||

tally from point E0 to point A—which it will not do unless |

|

|

|

|

|

the aggregate supply curve is horizontal. As the diagram clearly shows, output actually |

|

|

|||

rises by less, which is one reason why the oversimplified formula exaggerates the size of |

|

|

|||

the multiplier. |

|

|

|

|

|

RECESSIONARY AND INFLATIONARY GAPS REVISITED

With this understood, let us now reconsider the question we have been deferring: Will equilibrium occur at, below, or beyond potential GDP?

We could not answer this question in the previous chapter because we had no way to determine the equilibrium price level, and therefore no way to tell which type of gap, if any, would arise. The aggregate supply-and-demand analysis presented in this chapter now gives us what we need. But we find that our answer is still the same: Anything can happen.

The reason is that Figure 3 tells us nothing about where potential GDP falls. The factors determining the economy’s capacity to produce were discussed extensively in Chapter 7. But that analysis could leave potential GDP above the $6,000 billion equilibrium level or below it. Depending on the locations of the aggregate demand and aggregate supply curves, then, we can reach equilibrium beyond potential GDP (an inflationary gap), at potential GDP, or below potential GDP (a recessionary gap). All three possibilities are illustrated in Figure 5 on the next page.

The three upper panels duplicate diagrams that we encountered in Chapter 9.2 Start with the upper-middle panel, in which the expenditure schedule C 1 I1 1 G 1 (X 2 IM) crosses the 45o line exactly at potential GDP—which we take to be $7,000 billion in the example. Equilibrium is at point E, with neither a recessionary nor an inflationary gap. Now suppose that total expenditures either fall to C 1 I0 1 G 1 (X 2 IM) (producing the upperleft diagram) or rise to C 1 I2 1 G 1 (X 2 IM) (producing the upper-right diagram). As we read across the page from left to right, we see equilibrium occurring with a recessionary gap, exactly at full employment, or with an inflationary gap—depending on the position

2 Recall that each income-expenditure diagram considers only the demand side of the economy by treating the price level as fixed.

Copyright 2009 Cengage Learning, Inc. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part.

LICENSED TO:

206 |

PART 2 |

The Macroeconomy: Aggregate Supply and Demand |

FIGURE 5

Recessionary and Inflationary Gaps Revisited

|

|

Potential |

Potential |

|

|

Potential |

|

|

|

|

GDP |

|

GDP |

|

|

GDP |

|

|

|

|

45° |

|

|

45° |

|

45° |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Expenditure |

|

|

|

|

|

|

B |

E |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Inflationary |

|

|

|

|

C + I0 + G + |

|

|

|

gap |

|

|

|

|

(X – IM) |

E |

C + I1 |

+ G + |

|

C + I2 + G + |

|

|

|

|

|

|

(X – IM) |

|||

Real |

|

|

|

|

(X – IM) |

|

|

|

E |

|

Recessionary |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

B |

gap |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

6,000 |

7,000 |

7,000 |

|

|

7,000 |

8,000 |

|

|

|

Real GDP |

Real GDP |

|

|

Real GDP |

|

|

|

|

Potential |

Potential |

|

|

Potential |

|

|

|

|

GDP |

|

GDP |

|

|

D2 GDP |

|

|

|

|

S |

|

|

S |

|

S |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

D1 |

|

|

|

B |

E |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Inflationary |

D2 |

Level |

D0 |

|

|

|

|

|

gap |

|

|

|

E |

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

E |

|

Recessionary |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Price |

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

B |

gap |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

D1 |

|

|

||

|

S |

|

S |

|

|

S |

|

|

|

|

|

D0 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

6,000 |

7,000 |

7,000 |

|

|

7,000 |

8,000 |

|

|

|

Real GDP |

Real GDP |

|

|

Real GDP |

|

|

NOTE: Real GDP is in billions of dollars per year.

of the C 1 I 1 G 1 (X 2 IM) line. In Chapter 9, we learned of several variables that might shift the expenditure schedule up and down in this way. One of them was the price level.

The three lower panels portray the same three cases differently—in a way that can tell us what the price level will be. These diagrams consider both aggregate demand and aggregate supply, and therefore determine both the equilibrium price level and the equilibrium GDP at point E—the intersection of the aggregate supply curve SS and the aggregate demand curve DD. But there are still three possibilities.

In the lower-left panel, aggregate demand is too low to provide jobs for the entire labor force, so we have a recessionary gap equal to distance EB, or $1,000 billion. This situation corresponds precisely to the one depicted on the income-expenditure diagram immediately above it.

In the lower-right panel, aggregate demand is so high that the economy reaches an equilibrium beyond potential GDP. An inflationary gap equal to BE, or $1,000 billion, arises, just as in the diagram immediately above it.

Copyright 2009 Cengage Learning, Inc. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part.