- •A project of Liberty Fund, Inc.

- •Frank A. Fetter, Economics, vol. 1: Economic Principles [1915]

- •The Online Library of Liberty Collection

- •Edition used:

- •About this title:

- •About Liberty Fund:

- •Copyright information:

- •Fair use statement:

- •Table of Contents

- •FOREWORD TO ECONOMISTS AND TEACHERS

- •ECONOMIC PRINCIPLES

- •PART I

- •ELEMENTS OF VALUE AND PRICE

- •CHAPTER 1

- •PURPOSE AND NATURE OF ECONOMICS

- •Note

- •CHAPTER 2

- •CHOICE AND VALUE

- •Notes

- •CHAPTER 3

- •GOODS AND PSYCHIC INCOME

- •CHAPTER 4

- •PRINCIPLES OF EVALUATION

- •Note

- •CHAPTER 5

- •TRADE BY BARTER

- •CHAPTER 6

- •MONEY AND MARKETS

- •CHAPTER 7

- •PRINCIPLES OF PRICE

- •CHAPTER 8

- •COMPETITION AND MONOPOLY

- •PART II

- •USANCE AND RENT

- •CHAPTER 9

- •AGENTS FOR CHANGING STUFF AND FORM

- •CHAPTER 10

- •AGENTS FOR EFFECTING CHANGES OF PLACE AND TIME

- •CHAPTER 11

- •CONSUMPTION AND DURATION

- •CHAPTER 12

- •THE PRINCIPLE OF PROPORTIONALITY

- •CHAPTER 13

- •THE CONCEPT OF USANCE-VALUE

- •CHAPTER 14

- •THE RENTING CONTRACT

- •Note

- •CHAPTER 15

- •PRINCIPLES OF RENT

- •PART III

- •VALUABLE HUMAN SERVICES, AND WAGES

- •CHAPTER 16

- •HUMAN BEINGS AND THEIR ECONOMIC SERVICES

- •CHAPTER 17

- •CONDITIONS FOR EFFICIENT LABOR

- •CHAPTER 18

- •THE VALUE OF LABOR AND THE CHOICE OF OCCUPATIONS

- •CHAPTER 19

- •PRINCIPLES OF WAGES

- •Notes

- •PART IV

- •TIME-VALUE AND INTEREST

- •CHAPTER 20

- •TIME-PREFERENCE

- •Note

- •CHAPTER 21

- •RATE OF TIME-PREFERENCE

- •CHAPTER 22

- •MONEY AND CAPITALIZATION

- •CHAPTER 23

- •CAPITALIZATION OF MONETARY INCOMES

- •CHAPTER 24

- •SAVING AND BORROWING

- •CHAPTER 25

- •CAPITALIZATION AND INTEREST

- •PART V

- •ENTERPRISE AND PROFIT

- •CHAPTER 26

- •ENTERPRISE

- •CHAPTER 27

- •MANAGEMENT

- •CHAPTER 28

- •PROFITS AND COSTS

- •Notes

- •CHAPTER 29

- •VARIOUS SHADES OF PROFITS

- •CHAPTER 30

- •COSTS AND COMPETITIVE PRICES

- •CHAPTER 31

- •MONOPOLY-PRICES; LARGE PRODUCTION

- •PART VI

- •DYNAMIC CHANGES IN ECONOMIC SOCIETY

- •CHAPTER 32

- •THE PROBLEM OF POPULATION

- •Note

- •CHAPTER 33

- •VOLITIONAL DOCTRINE OF POPULATION

- •CHAPTER 34

- •DECREASING AND INCREASING RETURNS

- •Note

- •CHAPTER 35

- •BASIC MATERIAL RESOURCES: THEIR USE, CONSUMPTION, AND CONSERVATION

- •CHAPTER 36

- •MACHINERY AND WAGES

- •CHAPTER 37

- •WASTE AND LUXURY

- •CHAPTER 38

- •ABSTINENCE AND PRODUCTION

- •CHAPTER 39

- •VALUE THEORY AND SOCIAL WELFARE

Online Library of Liberty: Economics, vol. 1: Economic Principles

[Back to Table of Contents]

CHAPTER 29

VARIOUS SHADES OF PROFITS

§1. Review of the profit-concept. § 2. Skill in relation to risk. § 3. Union of chance and choice. § 4. Element of pure chance. § 5. Changes in transportation and in landvalues. § 6. The so-called unearned increment. § 7. Element of speculation in business. § 8. Specialization of risk-taking, in produce markets. § 9. Produce speculators as insurers. § 10. Ignorant and dishonest speculation. § 11. Fraudulent and illicit profits.

§1. Review of the profit-concept. Profit is the legal residual share of the total income yielded by an enterprise, the share (positive or negative, profit or loss) that is left to the owners of the enterprise. Every enterprise, however simple, involves ownership of agents and product, and between the investing and the accounting at the end of any period, there is financial responsibility and profit or loss. This may be minimized by one owner by contract with another, the one thus becoming more passive and safe, tho still having some risk, and the other, taking at a price the active control of wealth and services and selling the results for whatever he can get. The laborer still runs the risk of becoming incapacitated by illness or accident, or of being thrown out of employment. The lender still has some risk of failure of the debtor, etc. But the laborer sells his labor, and the capitalist sells the use of his wealth—horses, lands, equipment, and of his loanable capital, and accepts a definite income and the legal responsibility of the borrower to repay the loan.

§2. Skill in relation to risk. In most enterprises and under normal conditions of business the largest factor in determining whether there will be anything left for profits is the skill with which the business is planned and managed, from the first investment to the last little detail by the wellchosen agents of the enterprisers. There are many chances and risks, but few of them are completely objective, of a kind utterly beyond the control of the enterpriser. Even loss by lightning, flood, fire, and other “acts of God” (in legal phrase) are more or less liable according to the judgment and foresight in the construction and location of buildings, care in their oversight, etc. This power to minimize risk, the restless watchfulness and the intuitive anticipation of dangers, and often the discovery of ways to convert them into advantages, is a large part of what is meant by skill of management. The risk of business is not that of the throwing of dice in which (if it is fair) skill plays no part, and gains in the long run offset losses. Business risk is rather that of the rope-walker in crossing Niagara; the task is easily undertaken by the skilful Blondin, it is fatally dangerous to the man of unsteady nerve and limb. The skilled workman, handling, with sure touch, the delicate and costly materials, can not be said to be incurring a great risk of spoiling his work, however great the risk to the novice or the bungler.

Looking at this large phase of the problem, profits are seen to be due not to the existence of risks, but to comparative skill in taking risks which in many cases is the

PLL v4 (generated January 6, 2009) |

210 |

http://oll.libertyfund.org/title/2088 |

Online Library of Liberty: Economics, vol. 1: Economic Principles

ability to make the risk dwindle or disappear. Some men are more able to perform the function of enterprise than others, and profits are high or low just as fruits are bountiful on fertile soil and scanty on barren soil. In this aspect profits in the long run are the share (non-contractual) of skill and ability in the function of enterprise; and our illustrations above have largely been drawn from industries in which this seems to be the true view.

§3. Union of chance and choice. But there is another aspect of the subject. Profits, just because it is the actual residual, is the most complex and varying share. The enterpriser, to the extent of his credit and financial strength, undertakes to assume the risks for all the other factors. Profits is the catch-all for every unforeseen or variable change of price between each act of investment and the ultimate sale of the goods. Chance therefore has its part; but the temptation is to exaggerate its importance. Many cases of profit said to be due to chance are found on closer knowledge to be due to superior judgment. They result from a union of happy chance with deliberate choice. The adventurer who, on the discovery of gold, goes at once to California or to Alaska, may stumble upon a gold-mine. It is luck; but he has gone to a place where goldmines are comparatively plentiful. If he stays at home it is more likely that he will stumble over an ash-heap. Throughout life there is constant opportunity, but it must be sought. One who has the good judgment to be ever at the right time at the place where he has the best chance of finding a good thing, usually gets the advantage, and men call it luck. The more the causes of success in general are studied, the larger is found the element of choice, the smaller that of luck.

§4. Element of pure chance. But after all these qualifications, cases remain in which profits can only be said to be the result of pure chance or luck. It still sometimes appears better to be born lucky than to be born rich. What is luck? A result that is not calculable, coming to pass in conditions where a rational choice is not possible, is called luck, for lack of another name. There is bad luck as well as good luck. According to the law of chance, in the tossing of a coin for “heads or tails,” one side is as likely to come up as the other, and in the long run the number of heads and tails will be equal. Taking all together the pure accidents of certain kinds, in the community, they are so numerous that losses and gains distribute themselves about a general average by what is called the law of averages, or the law of large numbers. The individual’s risk then may be eliminated by insurance, as that against fire, flood, lightning, against sickness of the employer, which would cripple the business, or against his death, which would check it. But many factors evade all attempts to reduce them to rule and there is no possibility of insuring against them: war, changes in markets, good and bad harvests, financial crises, etc. One year the enterprise gains, another it loses. One man makes a success because he happened to engage in business at that time, another man fails because he happened to undertake it at another time, with no more real judgment in the one case than in the other.

§5. Changes in transportation and in land-values. The union of choice and chance in varying proportions is seen in many instances of the increase in the value of land. The rapid changes in transportation since the beginning of the nineteenth century have wrought great changes in the value of lands for many purposes, and thus have brought great chance profits (and often great losses) to individuals. To take a few examples.

PLL v4 (generated January 6, 2009) |

211 |

http://oll.libertyfund.org/title/2088 |

Online Library of Liberty: Economics, vol. 1: Economic Principles

The Erie Canal, completed in 1825, increased the trade of the ports of New York and Buffalo, brought prosperity to many cities on its waters, increased the value of agricultural lands on and near the Great Lakes, but reduced the value of many farms in New York and New England. The completion of the Boston and Albany railroad in 1841 and the later opening of the Hoosac tunnel probably helped the mechanical and depressed the agricultural industries of New England. The spread of the railroads in the United States from 1850 to 1880 went on with unparalleled rapidity, and opened up to settlement great areas of rich lands which rose in value. At the same time the large new supplies of agricultural produce so reduced prices in the great markets, and the incomes from lands in eastern America and in western Europe fell so greatly that many farmers were bankrupted. Timber lands bought from the government at fifty cents an acre made enormous fortunes for the so-called “lumber kings” of the Northwest. The Panama Canal raised the efficiency of ships plying between New York and San Francisco, enabling them to carry freight more quickly and in greater amounts. The railroads must lower some freight rates and even then lose a part of their traffic, and many of the lands on the Pacific coast must rise in value.

Changes in transportation alter the location and character of all kinds of enterprises. After the building of the railroads in Pennsylvania new forges were built where deposits were richer or where materials and products could be more cheaply shipped, and many prosperous small forges on the country roads became valueless. A similar change has relocated the flour milling, the mechanical, and the textile industries of a large part of the country. As population has been growing rapidly in Christendom in the past century or more, farms have become villages, villages have become cities, lowpriced residential lots have become expensive business sites.

§ 6. The so-called unearned increment. Such changes and chances as these have resulted in profits and losses to great numbers of landowners, who as investors have seen their lands rise above or fall below the price for which they bought the land. The name “unearned increment” has frequently been applied especially to this kind of profit of the landowner. It is true that in many ways the ownership of a piece of land may give unexpected gains. Farm land of the poorest kind often is found to contain valuable mineral deposits. Such a lucky find lifted the mortgage from a farm in eastern Pennsylvania, from which, in two or three years, feldspar was taken exceeding in value the agricultural products of the same land in the fifty years before. The discovery of building stone, coal, natural gas, or oil beneath the surface has brought riches to many a poor landowner. A mineral spring, because of the supposed or proved healing properties of its waters, may be as good as a mine. Fitness to produce nettles is not ordinarily a virtue in land, but the discovery that certain fields produce a superior quality of the nettle used for heckling cloth, causes them to rise in price. Marsh land, almost valueless, found to be peculiarly fitted for the cultivation of celery, becomes very valuable. While the income of the owners of these lands is increased, that of other owners may be diminished, as a result of the fall of prices and the shift of demand.

The increment of land values seems especially unearned when it arises as an incident to the holding of the land for other purposes, as for farming, or for one’s own residence. The striking fact in the extreme cases of chance increments of land values

PLL v4 (generated January 6, 2009) |

212 |

http://oll.libertyfund.org/title/2088 |

Online Library of Liberty: Economics, vol. 1: Economic Principles

is that profits accrue to quite unenterprising landowners. Many dramatic changes of fortune have resulted and in many a case some half-miserly old farmer doing nothing to improve the community and opposing all change, has left a fabulous fortune to his heirs. And yet, comparatively speaking, such cases are about as rare among landowners as are capital prizes in a lottery, and there are many cases of profit in things other than lands, where there is a similar profit due to chance. Stocks of goods are worth more or less, horses, cattle, grain, go up and down in price in the hands of farmers or of produce merchants. All profit involves this element. Land profit is but one notable example of a general fact.

Moreover, while the change of land values is on the whole upwards where population is increasing, many pieces of land fall in price; there are undeserved decrements as well as unearned increments. So far as increases in land value can be foreseen they are included in the present worth of the land, and the new purchaser does not thereafter, viewed as an investor, get any “unearned” increment except from unforeseen or miscalculated changes.

As a matter of the theory of profits there is nothing peculiar in the unearned increment of land. A question calling for separate consideration is whether it is expedient to adopt a different policy as to property in land, by special landtaxation, or by appropriating the profit (increment) which now goes to the owners in advancing neighborhoods, or by any other limitations.

§ 7. Element of speculation in business. A still further specialization of risk-taking is effected by means of insurance and of certain forms of speculation. In its broadest sense speculation means looking into things, examining attentively, studying deeply. In a business sense the speculator is one who studies carefully the conditions and the chances of a change of prices; hence arises the thought that speculation is connected with chance. The enterpriser should be able to estimate these chances better than most men. Every enterpriser is to some extent specializing as a risk-taker. He relieves the other agents of part of the risk, and he insures both laborer and capitalist against future fluctuations of prices. Some of the profits of successful enterprise are speculative gains of this sort. Offsetting them, however, in large measure, are the speculative losses, by which in many cases the investment is swept away altogether. The cautious business man tries to reduce chance as much as possible by insurance, where a regular system prevails, and to confine his thought and worry to the parts of the productive process where his ability counts in the result. A man can better concentrate his thought and effort upon running a flour mill, if some one else will, for a price, take the risks of fire, of loss in shipment, and of a rise in the price of grain needed to fill outstanding orders. Insurance being the economical way to cover risk, the reckless will, in the long run, more likely be eliminated from the ranks of enterprisers.1

PLL v4 (generated January 6, 2009) |

213 |

http://oll.libertyfund.org/title/2088 |

Online Library of Liberty: Economics, vol. 1: Economic Principles

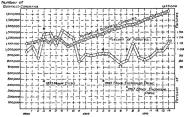

Fig. 45. Business Failures in the U.S., 1890-1914.*

§8. Specialization of risk-taking in produce markets. In some lines the risk of marketing and carrying large stocks becomes highly specialized, so that ordinary enterprisers shift it to a small group of risk-takers. In buying and selling large quantities of produce there is required the closest and most exclusive attention of a small group of men. The marketing of some staple products requires the most minute acquaintance with world conditions. To foretell the price of wheat one must know the rainfall in India, the condition of the crop in Argentina, must be in touch as nearly as possible with every unit of supply that will come into the world market. Such knowledge is sought by the great produce speculators in the central markets. If all means of communication—telegraph, cables, mails—are open to all, competition among these speculators becomes intense, and the result is great efficiency. Their survival depends on the development of acute insight into market conditions. The margin at which farm produce is sold in the great wholesale markets is a very narrow one. These products are marketed along the lines of the least resistance; that is, of the greatest economy. The function of the commercial specialists is to foresee the markets, and to ship to the best place, at the right time, in the right quantities. If a product shipped to Liverpool will, by the time it arrives there, be worth more in Hamburg, there is a loss. Such difficult decisions can be made best by a small group of men selected by competition. When handling actual products they perform a real economic service.

§9. Produce speculators as insurers. Many of the speculators in staples, wheat, corn, wool, rarely handle the material things, the real products. They make it their business to study the world conditions and to buy or sell for future delivery. Regular merchants buy and sell “futures” from or to these men; that is, they promise to deliver or take the produce or pay the difference between the contract and the actual price at the time of maturity. Mere speculators on the produce markets may and do at times thus perform service as risk takers. When a miller buys ten thousand bushels of wheat that will remain in the mill three months before they are marketed as actual flour, he “hedges”; that is, he at the same time sells that number of bushels to a speculator for future delivery. If wheat goes down in price the loss on the actual wheat is balanced by the gain on the “future,” and vice versa. Or selling flour for future delivery the miller buys a future in wheat; if wheat goes up in price, the miller’s loss on his contract for flour is offset by the gain on the “future.” In either case he cancels the chance of loss or gain, giving up the chance of profit in the rise of wheat in exchange for protection from the loss of the product on his hands. To him this is legitimate insurance, for he is striving not to create an artificial risk, but to neutralize one that is inseparable from the ordinary conditions of his business.

PLL v4 (generated January 6, 2009) |

214 |

http://oll.libertyfund.org/title/2088 |

Online Library of Liberty: Economics, vol. 1: Economic Principles

How can the speculator profit if the miller in the long run benefits? There are unsuccessful speculators and at any rate their losses go to the successful as a sort of gambling profit. But, further, the sales to legitimate purchasers should net a gain to the abler speculator. In proportion as his estimates are correct, there will remain a regular slight margin of profit to him. If he sells wheat at eighty-five cents to be delivered in three months, he expects it to be a little less at that time; if he buys a future he expects the price to be a little more at that time. In the long run the speculator to be successful must buy at a little less and sell at a little more than the price really proves to be. This means that the merchants in the long run pay something for protection against changes in prices, just as they pay something for insurance. And yet this is the cheapest way to reduce risk, and a man engaged in milling is, it is said, at a disadvantage if he neglects this method of insurance.

§10. Ignorant and dishonest speculation. What has just been described is the more legitimate phase of buying on margin, not its darker aspect. One who, having no special opportunities to know the market, buys or sells wheat, or other commodities or securities, on margin, is called a “lamb.” He is simply betting. He has no unusual skill; he can not foresee the result. The commission paid to brokers “loads the dice” slightly; the opportunities of the larger dealer of anticipating information load the dice heavily against the “lambs.” Secret combinations and all kinds of false rumors cause fluctuations large enough to use up the margins of the small speculator. At times a number of powerful dealers unite to cause an artificially high or low price, a situation called “a corner,” in which both other professional speculators and the outsiders are made to pay heavily. But this is little other than gambling between bettors.

§11. Fraudulent and illicit profits. Interwoven with profits in many cases is a dark thread of fraud. Caveat emptor is by law the rule of the market, and the salesman often uses the subtle arts of misrepresentation. Undoubtedly honesty is the best policy, but it is not always the most profitable policy in a pecuniary sense. Cheating, lying, breaking of contracts, bribery of public officials, and many similar acts may increase individual incomes. One man gains a temporary success by acts that are later punished as crimes; another, guilty of like deeds, escapes conviction for lack of evidence or on technicalities, and enjoys ill-gotten wealth. More fortunes, however, are due to actions on the border-line of law which society is not yet wise enough to condemn or efficient enough to prevent. No code of laws can be framed that will make possible the punishment of all evil acts in trade. Any law that would catch all the guilty would injure many of the innocent. The efforts of social reformers are being directed toward detecting and preventing the fraud, intimidation, and extortion that still make up no inconsiderable part of private profits. It may be noted that under the English common law, for centuries past, monopoly has been tainted with illegality, so that all monopoly profits that are not legally protected (such as incomes from patents, copyrights, fairly obtained franchises, etc.) must be classed under this heading.

PLL v4 (generated January 6, 2009) |

215 |

http://oll.libertyfund.org/title/2088 |