Political Theories for Students

.pdf

L i b e r a l i s m

the original statement of the social liberal position of the need for a liberal state to provide positive freedoms for its citizens.

Hayek, F.A. New Studies in Philosophy, Politics, Economics and the History of Ideas, Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1978. Hayek’s essay “Liberalism” is a re–statement of classic liberal doctrine in the late–twentieth century context when liberalism was re–emerging as a dominant doctrine in the developed countries.

Mill, John Stuart On Liberty and Other Essays, John Gray, ed., Oxford University Press, 1991. This collection of 1859 essays contains many of the key statements by the most influential English liberal theorist of the nineteenth century.

SEE ALSO

Capitalism, Conservatism, Federalism

1 9 2 |

P o l i t i c a l |

T h e o r i e s |

f o r |

S t u d e n t s |

OVERVIEW

Despite the obstacles of many centuries, national boundaries, and terminology confusion, the tradition known since the 1950s as libertarianism forms a coherent legacy from its founding by fathers John Locke and Adam Smith in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries through its organization as a U.S. political party in 1971 and beyond. This individualist political theory has spawned classic works, inspired revolutions, fueled activist movements, and earned Nobel Prizes. Its history has included a rise and decline, and the end of the twentieth century revealed a reemergence for this long–lived tradition. Individual rights, property, constitutionalism, and universalism form the heart of libertarianism.

Libertarianism

WHO CONTROLS GOVERNMENT? Restricted officials

HOW IS GOVERNMENT PUT INTO POWER? Group

dissatisfied with previous powers

WHAT ROLES DO THE PEOPLE HAVE? Enjoy rights while

not infringing on others

WHO CONTROLS PRODUCTION OF GOODS? Private

individuals

WHO CONTROLS DISTRIBUTION OF GOODS? Private

individuals

MAJOR FIGURES Ayn Rand; Russell Means

HISTORICAL EXAMPLE Austrian School of Economics

HISTORY

It is not unusual for the term libertarianism to bring blank stares from theorists and politicians alike; one joke suggests that a libertarian is what you get when you cross a libertine with a librarian. Although the term libertarianism is rather new, the political theory it represents—at different times also called liberalism or classical liberalism, among various other things—can be traced back to classical thought. An intellectual child of the West, libertarianism gained supporters and lost momentum in its long history, only to enjoy a new popularity around the globe at the end

1 9 3

L i b e r t a r i a n i s m

CHRONOLOGY

1690: John Locke’s Two Treatises of Civil Government is published.

1776: The Wealth of Nations by Adam Smith is published.

1871: Carl Menger founds the Austrian School of Economics.

1943: Ayn Rand introduces the Objectivist Movement with the publication of The Fountainhead.

1944: Friedrich Hayek’s Road to Serfdom is published.

1962: Calculus of Consent by James Buchanan and Gordon Tullock is published.

1971: The U.S. Libertarian Party is organized.

of the twentieth century and the beginning of the twenty–first. The broad principles of libertarianism allowed the tradition to grow, evolve, and adapt to new political and technological realities across the planet and centuries.

The first seeds of libertarian thought appeared in ancient Greece and Rome. For example, the Greek Sophists embraced the idea of equality among individuals; some went so far as to criticize the prevailing belief in natural slavery. The Athenian Pericles (c. 495–429 B.C.) praised the Greek polis and its system of equality under the law in his famous Funeral Oration. Friedrich Hayek (1899–1992), noted Austrian economist, Nobel Laureate, and libertarian, recognized the Roman statesman Cicero (106–43 BC) as the most influential precursor to libertarianism due to his defense of the concept of natural law. After antiquity, the influence of monotheism—the belief in one god for all—through Judaism and, later, Islam and Christianity reinforced the idea of one central law to which all people are held accountable.

The development of Christianity, in particular, brought new dimensions to proto–libertarian thought. After the Christian church split between East and West (1054), both sides offered important ideas to the young political theory. The Eastern church fathers from the Alexandrine School and beyond contem-

plated the perfectibility of humanity as a theological question. This added the issue of human flourishing and self–betterment to the political dialogue, which anticipated later German contributions to libertarian theory. In the West, especially in the Middle Ages, church leaders preserved the classics in general and studied economics and political science in particular. Different orders and communities developed specialties. For example, the Spanish School of Salamanca combined the study of Greek, Islamic, and Christian philosophy to develop a theory of market prices that informed later economic arguments borne of the Scottish Enlightenment. The second split of Christianity, that of the Reformation (begun in 1517), led to a similar dual influence on libertarianism. Catholic thought continued to explore natural law theory while Protestantism, with its “priesthood of the believer” doctrine, introduced a more potent individualism to the political landscape.

Political changes also added ingredients to the tradition. The rise of absolutism in Europe challenged the political, economic, and social freedom of the people. Opponents of powerful kings in England developed the myth of the ancient constitution—a notion of an ideal contract formed over time between ruler and ruled, government and governed, and solidified by the Anglo–Saxons before the Norman invasion of 1066—to justify their claims to individual rights and their conviction that monarchs were not above the law. As early as the English Civil War (1642–1651), political groups such as the Levellers wanted to take the ancient constitution concept a step further and develop a written constitution to mirror the idealized political compact between the people and their state. Perhaps the best example of proto–libertarian thought was Leveller John Overton’s 1746 work An Arrow Against All Tyrants, which articulated a theory of individualism, property, and limited government in order to call for a written constitution.

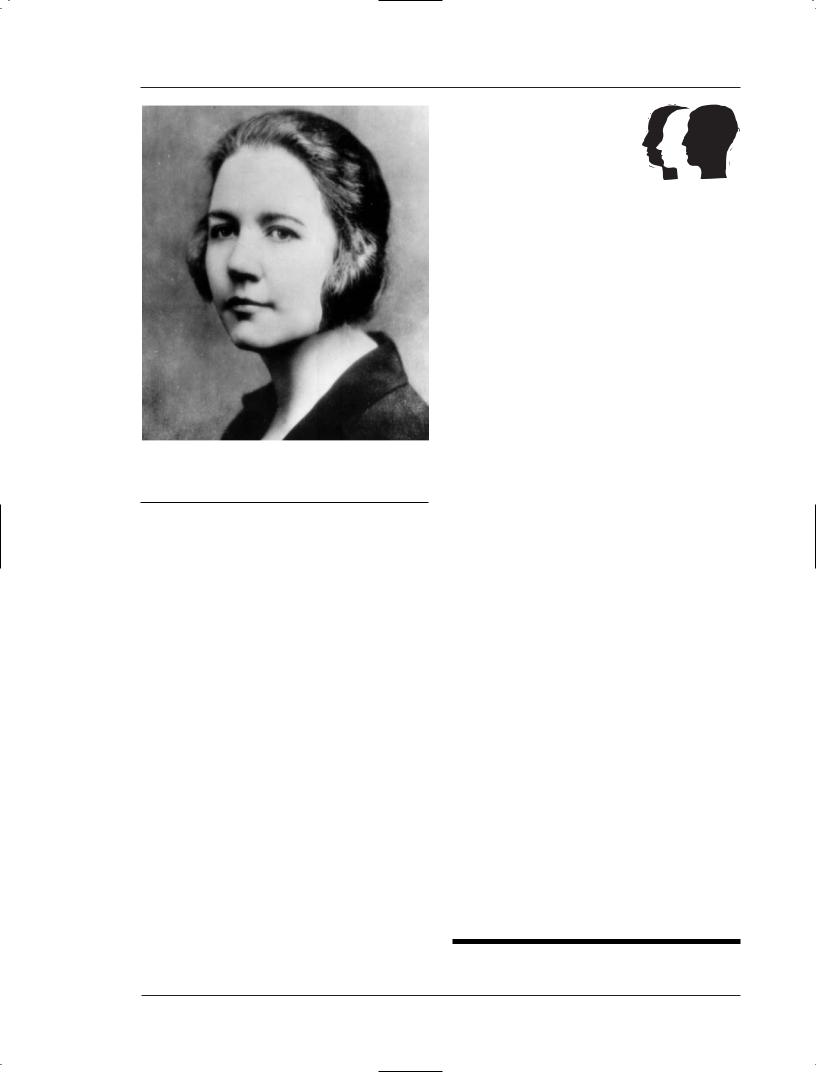

John Locke

Though clear precursors to libertarianism had existed for centuries, the theory itself awaited a systematic, definitive treatment. John Locke (1632–1704) provided this careful and comprehensive discussion and therefore became known as one of the fathers of libertarianism. In groundbreaking works such as A Letter Concerning Toleration (1689), Two Treatises of Civil Government (1690), Some Considerations of the Consequences of the Lowering of Interest, Raising the Value of Money (1692), and A Vindication of the Reasonableness of Christianity (1695), the English Locke made three important contributions to libertarian theory.

1 9 4 |

P o l i t i c a l |

T h e o r i e s |

f o r |

S t u d e n t s |

L i b e r t a r i a n i s m

John Locke. (The Library of Congress)

First, he examined the nature of individual rights. He argued that individuals were not bound to obey governmental laws that ignored their rights and therefore contradicted natural law. Second, Locke articulated a positive view of human nature that challenged the prevailing view of humans as incapable of peaceful coexistence without intrusive state interference. Third, he explained the idea that governments derived legitimacy from the consent of the governed. The compact, or agreement, between the state and its citizens placed duties on both; if the government failed to meet its responsibilities and breached the contract, citizens, according to Locke, possessed the right to revolt. Last, Locke argued that liberty was dependent on private property. A state that protected private property ensured the freedom of its citizens. Locke defined property as an act of creation—mixing labor with land grew crops, which therefore were property—and thus expanded the term to include political ideas, religious beliefs, and even an individual’s self. Locke’s contribution to political theory in general and libertarianism in particular cannot be overstated.

The Scottish Enlightenment

The first movement of libertarianism took place on the heels of Locke’s foundational work, and this time it originated in Scotland. The Scottish Enlightenment (1714–1817) began with the 1714 publication of

BIOGRAPHY:

John Locke

John Locke was born in 1632, the son of a Puritan country lawyer of Wrighton. He taught Greek and rhetoric at Oxford while completing his studies in medicine and science. His interests turned to moral and political theory thanks to his father’s enthusiasm for the parliamentary cause during the English Civil War and the influences of his colleagues—specifi- cally, his friendship with Lord Ashley and his relationship with Robert Boyle through the Royal Society. Locke held minor official positions until the Duke of York took the English throne in 1683, which forced Locke to flee to Holland. Locke returned to his homeland after the Glorious Revolution to widespread popularity, new positions, and favor in the eyes of William and Mary. He published numerous works of political theory and philosophy in many languages. His most influential books include A Letter Concerning Toleration (1689), Two Treatises of Civil Government (1690), Some Considerations of the Consequences of the Lowering of Interest, Raising the Value of Money (1692), and A Vindication of the Reasonableness of Christianity (1695).

Locke’s greatest contribution to political theory was his systematic exploration of the concepts that compose libertarianism; his was the first such comprehensive treatment of the tradition. For example, he explored the ideas of natural law, private property, and toleration, and he examined the nature of the social contract, the implicit agreement binding the government to the governed. He argued that all individual rights ultimately draw justification from self–owner- ship, through which a person’s thoughts, beliefs, possessions, and labors are his or her own. His defense of life, liberty, and property—and the right of revolution for citizens whose government fails to protect these rights—influenced revolts such as the American and French Revolutions, documents such as the American Declaration of Independence, and even activism such as the U.S. Civil Rights Movement. By illuminating the values and issues of individualism, Locke provided the framework for an ongoing dialogue and earned the title of father of libertarianism.

P o l i t i c a l |

T h e o r i e s |

f o r |

S t u d e n t s |

1 9 5 |

L i b e r t a r i a n i s m

BIOGRAPHY:

Adam Smith

Adam Smith’s father died before his son and namesake was born in Scotland in 1723. The junior Adam Smith studied at the University of Glasgow, where he was influenced greatly by Professor Francis Hutcheson. Hutcheson introduced Smith to the realm of moral philosophy, which included natural religion, morals, jurisprudence, and government. Smith longed to discover a natural law to explain human action in the same way that Isaac Newton articulated laws for the natural world. His first work, 1759’s The Theory of Moral Sentiments, suggested that people are motivated by the need for approbation. Individuals, Smith argued, know what society expects of them thanks to internal “impartial spectators,” mechanisms that remind people of the approval and/or disapproval of others.

This effort, at once psychological, sociological, and anthropological, was followed by the 1776 tome

An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations, which added economics to the list of Smith’s achievements. In this work, Smith identified the division of labor as the key to increased production, and therefore wealth. He defined the ingredients of price as rent, wages, and profit—an insight that became a standard fact of elementary economic understanding. Smith’s most famous contribution, however, was the metaphor of the invisible hand to describe the spontaneous order of free markets and the natural harmony of interests they produce.

Smith’s gift lay in synthesizing large amounts of detailed information into a useful, interdisciplinary analysis and translating his understanding to language many people could understand. He believed that liberty could focus self–interest into socially beneficial activity, and his works communicated his message successfully. His writings were translated into many languages during his lifetime and they remain classics; his scientific approach to issues of freedom complemented the theoretical views of Locke and made Smith the second father of libertarianism.

Bernard Mandeville’s Enquiry into the Origin of Moral Virtue, or The Fable of the Bees. This controversial book suggested self–interest, not morality, fueled the actions of individuals; it also marked a shift from interest in political theory to more expansive attention on economic and philosophical matters with regard to individual liberty. Adam Ferguson (1723–1816), David Hume (1711–1776), and Henry Homes, or Lord Kames, continued the movement with contributions in history, political science, philosophy, and economics. Perhaps the most noteworthy member of the Scottish Enlightenment also became known as the second fa- ther—the co–parent with John Locke—of libertarianism: Adam Smith (1723–1790). Smith did for moral philosophy and economics what Locke had done for political theory. In his most famous work, the 1776 An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations, Smith drew a portrait of societies in which people acted out of self–love, and yet the unplanned, uncoordinated market, or “invisible hand,” coordinated their decisions and provided for the common good. His vision of the harmony of interests created by free trade made Smith not only the foremost economist of his era and the father of capitalism, but was also one of the lasting visionaries of libertarianism.

Other Western Influences

If libertarianism proper first came together as a coherent theory in England and Scotland thanks in part to the atmosphere of order, stability, and individualism provided by Whig leadership after the Glorious Revolution, then it blossomed in France, where its ideas rebelled against the more feudalistic French institutions of state and church. The first wave came in the form of the French Enlightenment (1717–1778). Key philosophers such as Voltaire, Baron de Montesquieu (1689–1755), and Marquis de Condorcet (1743–1794) challenged the intolerance and arbitrariness of established authorities and called for rational inquiry, free speech, and greater individual liberty. The French Enlightenment, then, was essentially a libertarian affair. The products of its greatest minds became some of the foundational literature of libertarian thought. A later, second movement, the French Physiocratic movement (1759–1776), was to economics what the French Enlightenment was to philosophy. Leaders such as Françoise Quesnay (1694–1774) and Jacques Turgot (1727–1781) argued against the traditional policy of mercantilism, which included the hoarding of precious metals as well as planned industry and protectionism, in favor of free trade, open markets, and limitations to government involvement in the economy. Put in practice, many of the French philosophers’ and physiocrats’ ideas—

1 9 6 |

P o l i t i c a l |

T h e o r i e s |

f o r |

S t u d e n t s |

L i b e r t a r i a n i s m

BIOGRAPHY:

Frederic Bastiat

If Adam Smith learned how to reach a broader audience with his ideas about free markets, then Frederic Bastiat made an art of it. Bastiat was born in Mugron, France in 1801. Deeply opposed to the protectionism practiced on behalf of some industries by the French state, Bastiat wrote to limit government intervention in the economy. He founded the Associations for Free Trade in 1846. The organization’s journal Le Libre–Change, or Free Trade, became a vehicle for Bastiat’s views. His most popular work, however, formed part of the 1845 book, titled in English Sophisms of Protection. In his “Candlemakers’ Petition,” Bastiat effectively parodied the rationale behind protectionism by presenting a fictional petition to the state: candlemakers asked for protection against the sun, explaining that candlemaking and related industries would profit greatly if the sun were eliminated as a competitor in providing light to the world. The ridiculousness of the petition underscored Bastiat’s critique of governmental interruption of markets on behalf of special interests and became a staple of economics texts for over a century thereafter.

Bastiat used metaphors to capture the imagination and opinion of his reading audience. In his essay “What is Seen and What is Not Seen,” he used the image of a boy breaking a window to explain opportunity cost—money spent on one thing costs the opportunity for that money to be spent on something else—and challenged the prevailing view that war and other acts of destruction actually benefited the economy.

Have you ever been witness to the fury of that solid citizen, James Goodfellow, when his incorrigible son has happened to break a pane of glass? If you have been present at this spectacle, certainly you must also have observed that the onlookers...seem with one accord to offer the unfortunate owner the selfsame...‘Everybody has to make a living. What would become of the glaziers if no one ever broke a window?’

Now, this formula of condolence contains a whole theory that it is a good idea for us to expose...in this very simple case, since it is exactly the same as that which, unfortunately, underlies most of our economic institutions.

Suppose that it will cost six francs to repair the damage. If you mean that the accident gives six francs’ worth of encouragement to the aforesaid industry, I agree...The glazier will come, do his job, receive six francs, congratulate himself, and bless in his heart the careless child.

This is what is seen.

But if, by way of deduction, you conclude, as happens only too often, that it is good to break windows, that it helps to circulate money, that it results in encouraging industry in general, I am obliged to cry out: That will never do! Your theory stops at what is seen. It does not take account of what is not seen.

It is not seen that, since our citizen has spent six francs for one thing, he will not be able to spend them for another. It is not seen that if he had not had a windowpane to replace, he would have replaced, for example, his worn–out shoes or added another book to his library. In brief, he would have put his six francs to some use or other for which he will not now have them....

From which, by generalizing, we arrive at this unexpected conclusion: ‘Society loses the value of objects unnecessarily destroyed’...‘Destruction is not profitable.’

Toward the end of his life, Bastiat opposed the rise of socialism and communism, which he saw to be inextricably linked with protectionism. His position won him seats in the Constituent Assembly and Legislative Assembly of 1849. He died shortly thereafter, hailed by the famous economic theorist Joseph Schumpeter as “the most brilliant economic journalist who ever lived.” Bastiat’s gift for metaphor allowed him to draw persuasive and enduring illustrations of libertarian economy theory and reach a new audience with the ideas of free markets.

pro–individual, anti–state—led directly to the French Revolution.

One of the characteristics of the rise of libertarian thought was the fact that the ideas evolved in different nations almost simultaneously, and different strains and traditions informed and influenced others. This was the case with the Democratic–Republicans

(1776–1820) in the English Colonies–turned–United States; much of the theory embraced by Thomas Jefferson (1743–1826), father of the Declaration of Independence, and James Madison (1751–1836), father of the U.S. Constitution, with regard to individual rights, natural law, and the social contract came from the British libertarian tradition. In turn, the U.S. interpre-

P o l i t i c a l |

T h e o r i e s |

f o r |

S t u d e n t s |

1 9 7 |

L i b e r t a r i a n i s m

MAJOR WRITINGS:

Social Statics

If John Locke and Adam Smith represented the mainstream foundation of libertarianism, then Herbert Spencer illustrated one of its peripheries. Spencer’s works revealed his search for a broad, holistic, scientific pattern to explain social phenomena; this contrasted with some other libertarian theorists’ belief that human action was too complex to be categorized or planned. Nonetheless, Spencer made one contribution that did find its way to the mainstream of libertarian theory: his law of equal freedom. This law proposed that, morally, every person should be free to do as he or she wills, provided that he or she does not infringe on anyone else’s freedom to do the same. In his 1850 Social Statics, Spencer’s logical means of following each argument to its ultimate conclusion led him to argue that, under the law of equal freedom, individuals have the right to ignore the state:

As a corollary to the proposition that all institutions must be subordinated to the law of equal freedom, we cannot choose but admit the right of the citizen to adopt a condition of voluntary outlawry. If every man has freedom of any other man, then he is free to drop connection with the state—to relinquish its protection and to refuse paying toward its support. It is self–evident that in so behaving he in no way trenches upon the liberty of others, for his position is a passive one, and while passive he cannot become an aggressor. It is equally self–evident that he cannot be compelled to continue one of a polit-

ical corporation without a breach of the moral law, seeing that citizenship involves payment of taxes; and the taking away of a man’s property against his will is an infringement of his rights. Government being simply an agent employed in common by a number of individuals to secure to them certain advantages, the very nature of the connection implies that it is for each to say whether he will employ such an agent or not. If any one of them determines to ignore this mutual–safety confederation, nothing can be said except that he loses all claim to its good offices and exposes himself to the danger of mal- treatment—a thing he is quite at liberty to do if he likes. He cannot be coerced into political combination without a breach of the law of equal freedom; he can withdraw from it without committing any such breach, and he has therefore a right to withdraw....

Nay, indeed, have we not seen that government is essentially immoral? Is it not the offspring of evil, bearing about it all the marks of its parentage? Does it not exist because crime exists? Is it not strong—or, as we say, despotic—when crime is great? Is there not more lib- erty—that is, less government—as crime diminishes? And must not government cease when crime ceases, for very lack of objects on which to perform its function? Not only does magisterial power exist because of evil, but it exists by evil. Violence is employed to maintain it, and all violence involves criminality. Soldiers, policemen, and jailers; swords, batons, and fetters are instruments for inflicting pain; and all inflection of pain is in the abstract wrong...Wherefore, legislative authority can never be ethical—must always be conventional merely.

tation of the right of revolution and the experience of constitution building influenced the French libertarian tradition. Writers such as Thomas Paine (1737–1809) and leaders such as the Marquis de Lafayette (1757–1834) divided their time between the continents to participate in both the American and French Revolutions. The anti–authoritarian individualism of the revolutionary age made it one of the high impact points of libertarianism; the theory quite literally changed the face of nations and the lives of millions.

Over the next century, different individuals pushed the Western consensus on political theory, much of which was libertarian, to further conclusions. Brits William Godwin (1756–1836) and Mary Wol-

stonecraft (1759–1797) introduced new ideas about self–perfectibility and feminism. Their political works also influenced art through their daughter, Mary Shelley of Frankenstein fame, and the Romantic poets in her circle. Another couple, the French Germaine de Stael (1766–1817) and Benjamin Constant (1767–1830) provided libertarian critiques of the French Revolution’s successes and failures. Wilhelm von Humboldt (1767–1835) produced a Germanic, Romantic notion of self–cultivation and liberty. Economists such as the French Jean Baptiste Say (1767–1832) and the English David Ricardo (1772–1823) brought new scientific tools to bear on the legacy of the Scottish Enlightenment and French

1 9 8 |

P o l i t i c a l |

T h e o r i e s |

f o r |

S t u d e n t s |

L i b e r t a r i a n i s m

Physiocrats. French theologian Felicite Robert de Lamennais (1782–1854) linked the idea of freedom of religion with the goal of state decentralization. The French Frederic Bastiat (1801–1850) took this a step further with journalistic writing in favor of the lais- sez–faire economics pioneered by Adam Smith.

The libertarian approach also influenced the humanities, as scholars such as the British Herbert Spencer (1820–1903) and American William Graham Sumner (1840–1910) applied the tools of science to anthropology and history in search of broad patterns of human behavior. The visibility of renowned thinkers such as Alexis de Tocqueville (1805–1859) and John Stuart Mill (1806–1873) brought even further attention and validity to the tradition. American Elizabeth Cady Stanton (1815–1902) articulated an activist libertarian feminism and organized the first U.S. bid for women’s suffrage. The international, interdependent work of such minds proved the importance and popularity of libertarian ideas during the nineteenth century.

Others experimented with putting these ideas into practice. For example, the Manchester School (1835–1859) in England organized in support of libertarian ideas such as free trade, or laissez–faire economics, international markets, and pacifism, and in opposition to outdated rules such as the medieval Corn Laws that granted government monopolies to certain producers and protected others from competition. Led by Richard Cobden, the movement succeeded in repealing laws and propelling advocates into national office. In the United States, the Transcendentalist Movement (1835–1882) took the views of Godwin, Condorcet, and Humboldt on human perfectibility and employed them in writings, speeches, and even experimental utopian communities. The passive resistance plan of Henry David Thoreau, which influenced modern world leaders from Gandhi to Martin Luther King, Jr., was but one lasting contribution of the Transcendentalists.

After centuries of proto–libertarian Western thought, libertarianism coalesced around the figures of John Locke and Adam Smith and went on to achieve prominence in the nineteenth century. A number of historical events conspired to make the time ripe for libertarian thought. European culture allowed scholars, philosophers, authors, and activists the opportunity to travel, compare notes, test assumptions, and communicate effectively. This exchange of information ensured that economic or political authoritarianism in the form of protectionism or absolutism could no longer confine citizens, since they readily could compare their lots with those across the border. It also meant that new ideas could have ripple effects across

MAJOR WRITINGS

Two Treatises of Civil

Government

Two Treatises of Civil Government appeared in 1690. In the Second Treatise, Locke posed the question: if individuals naturally are free, why should they ever choose to cede some of their natural rights to government? The answer, Locke argued, was that the state was necessary to protect property and liberty. Where protection ended, he continued, so did the legitimate authority of government:

123.If man in the state of nature be so free, as has been said; if he be absolute lord of his own person and possessions, equal to the greatest, and subject to nobody, why will he part with his freedom? Why will he give up this empire, and subject himself to the domination and control of any other power? To which ’tis obvious to answer, that though in the state of nature he hath such a right, yet the enjoyment of it is very uncertain, and constantly exposed to the invasion of others. For all being kings as much as he, every man his equal, and the greater part no strict observers of equity and justice, the enjoyment of the property he has in this state is very unsafe, very insecure. This makes him willing to quit this condition, which however free, is full of fears and continual dangers: and ’tis not without reason, that he seeks out, and is willing to join in society with others who are already united, or have a mind to unite for the mutual preservation of their lives, liberties and estates, which I call by the general name, property.

124.The great and chief end therefore, of men’s uniting into commonwealths, and putting themselves under government, is the preservation of their property. To which in the state of nature there are many things wanting....

131. But though men when they enter into society, give up the equality, liberty, and executive power they had in the state of nature, into the hands of the society, to be so far disposed of by the legislative, as the good of the society shall require; yet it being only with an intention in everyone the better to preserve himself his liberty and property; (for no rational creature can be supposed to change his condition with an intention to be worse) the power of the society, or legislative constituted by them, can never be supposed to extend further than the common good....

P o l i t i c a l |

T h e o r i e s |

f o r |

S t u d e n t s |

1 9 9 |

L i b e r t a r i a n i s m

Rose Wilder Lane, author and advocate of libertarianism.

national boundaries; the American and French Revolutions are good examples of this interplay between countries. Older policies such as mercantilism also failed during this period, leaving a vacuum for new approaches that libertarian ideas filled. In the dual realms of ideas and action, libertarianism found success in the nineteenth century.

Decline and Return

Many of the conditions in the West that led to the rise of libertarianism in theory and practice changed at the turn of the century, however. Rapid industrialization created new economic problems; ethnic pride and nationalism destroyed international trade and the flow of information; communism and Nazism not only increased the size and scope of government within nations, but also forced other countries to expand their states to meet the challenge of world war; depression left citizens dependent on entitlements rather than jealous of their individual rights. By the dawn of the twentieth century, libertarian thinkers offered quiet critique of a mainstream that had left their ideas behind. Two economic movements, the Austrian School (1877–pre- sent) and Chicago School (1927–present), formed to oppose the trend of centralized economic planning, but their voices remained on the periphery of the Western debate about political theory.

BIOGRAPHY:

Ayn Rand

Many of the most prominent libertarian theorists made their marks through specialized scholarship or political office. Ayn Rand, however, chose to communicate her individualistic beliefs through works of fiction and popular philosophy. The results left her a bestselling author and a one–woman intellectual movement. Born in St. Petersburg, Russia, Rand emigrated to the United States after the Bolshevik Revolution, where she was haunted by her experience with communist totalitarianism in Russia and her frustration toward the West’s drift toward socialism. Her first novel, We the Living, appeared in 1936, but her breakthrough work came in 1943 with The Fountainhead. She followed its tremendous success with non–fiction such as Capitalism: The Unknown Ideal (1946) and The Virtue of Selfishness (1964) and fiction such as

Anthem (1853) and Atlas Shrugged (1957). From 1961 to 1976, she also published The Objectivist Newsletter (renamed The Ayn Rand Letter in 1971) to support her views further.

In all of her works, Rand promoted the philosophy she called objectivism, a subset of traditional libertarianism. Objectivism, according to Rand, meant that individual effort and ability served as the sole source of genuine achievement; all individuals’ highest moral end was their own happiness, and any notion of a group threatened all people as individual rights–bearers. She believed that altruism and sacrifice for the so–called “common good” was a vice that rewarded non–producers and penalized creative entrepreneurs. Laissez–faire economic systems and limited states, she argued, created the best atmosphere for the exercise of talent and pursuit of happiness. Her fictional characters—creative individuals who escaped society to follow their own ends—became live through various film adaptations, and her books sold by the millions. In 1991, nine years after her death and fifteen after her newsletter ended publication, a Gallop Survey ranking the most influential literature in the United States found the fiction of Ayn Rand to be second in national influence, surpassed only by The Bible.

2 0 0 |

P o l i t i c a l |

T h e o r i e s |

f o r |

S t u d e n t s |

L i b e r t a r i a n i s m

The tide turned once again in favor of libertarianism in the middle of the twentieth century, however. The experience of world war, depression, and totalitarianism suggested that the short–term solutions of centralized planning, government intervention, and collectivism had not only failed to offer viable solutions, but also had created other problems in terms of everything from economic inefficiencies to political stalemates to human rights abuses. The simultaneous publication of four influential and contrasting works in 1943 and 1944—the Russian Ayn Rand’s philosophical novel The Fountainhead, the American Rose Wilder Lane’s political manifesto The Discovery of Freedom, the American Isabel Patterson’s journalistic commentary God of the Machine, and the Austrian Friedrich Hayek’s economic analysis The Road to Serfdom—heralded the return of libertarianism as, if not a mainstream consensus, at least a credible voice of opposition. In 1944, Friedrich Hayek’s The Road to Serfdom helped to usher in the reemergence of libertarianism on the Western, and eventually world, stage; it remains the most well known work of libertarianism’s most long–lived movement, the Austrian School of Economics. In this work, Hayek warned that centralized economic planning by its very nature would lead to totalitarianism in whatever nation it was practiced.

The laissez–faire economic approaches of the Austrian and Chicago schools gained ground among scholars, and Ayn Rand’s individualistic Objectivist Movement (1943–1976) appealed to a popular audience, as well. By 1971, a third political party, the Libertarian Party, had formed in the United States with a platform supporting free markets, civil liberties, non–intervention, peace, and free trade.

No single success illustrated the reemergence of libertarianism better than the Public Choice School of Economics (1969–present). Founded after the 1962 publication of The Calculus of Consent by James Buchanan (1919– ) and Gordon Tullock (1922– ), the movement analyzed public policy from a market angle. Accordingly, they viewed politics as exchange, and asserted that politicians, lobbyists, bureaucrats, and others involved in policymaking acted with the same self–interest that motivates other actors in the private sector. This idea led to a myriad of methodological innovations in economics, political science, and public policy studies, and supported libertarian conclusions about the limitation of state power. This approach held important implications for analyzing government and policy, and by the twenty–first century had inspired everything from the New Economic History methodology to the burgeoning field of free market environmentalism, with influences felt as far

and wide as the United States, India, China, and the former Soviet bloc. Buchanan cemented his legacy by cofounding (1969) and for a time directing the Center for the Study of Public Choice. His work with the libertarian–inspired public choice theory earned him a Nobel Prize in Economics in 1986.

The new millennium opened with a record number of libertarian organizations and institutions worldwide devoted to political, economic, historical, and philosophical inquiry. In 2000, a Rasmussen Research poll revealed that 16 percent of U.S. citizens were ideologically libertarian; in the same year, the Libertarian Party’s candidates for the U.S. House of Representatives won 11.9 percent of the vote, which set a record for votes received for any third party in the nation’s history. The tradition born in antiquity and raised in the Enlightenment found new life in the Information Age.

THEORY IN DEPTH

Defining Libertarianism

A tradition as long–lived and diverse as that of libertarianism often suffers problems of definition. In fact, many who embraced or embrace libertarianism would disagree even about the name of the political theory. Until Leonard Read, founder of the Foundation for Economic Education, began to call himself a libertarian in the 1950s, no one had applied the term to the tradition. Before that, depending on the time and place, libertarians might have self–identified as individualists, voluntaryists, whigs, radical republicans, democratic–republicans, free thinkers, or liberals; moreover, proponents of individual movements within the libertarian framework often adopted the labels of the subset—from the Levellers and the Transcendentalists to the Austrian economists and objectivists— rather than the larger title. To complicate things further, there remains a strong urge from many within the libertarian community to disassociate with the frequently misunderstood term “libertarianism” and use the name “classical liberalism” instead.

Considering the complexity of the terminology issue, it is not surprising that those who try to define the tradition do so in somewhat different ways. For example, E. K. Bramsted, co–editor of the monumental anthology Western Liberalism: A History in Documents from Locke to Croce (1978), asserted that libertarianism champions 1) the rights of individuals, with careful attention to the more endangered rights of minorities, 2) the right of property in particular, 3) the government’s obligation to protect property, 4)

P o l i t i c a l |

T h e o r i e s |

f o r |

S t u d e n t s |

2 0 1 |