Political Theories for Students

.pdf

M a r x i s m

CHRONOLOGY

1818: Karl Marx is born.

1848: Marx and Engels complete The Communist Manifesto.

1867: The first edition of Karl Marx’s Das Kapital is published

1883: Karl Marx dies.

1889: The Second International is founded.

1902: Lenin publishes What Is to Be Done?

1917: Bolsheviks, led by Lenin, gain control in Russia.

1919: Founding of the Third International.

1922: Stalin becomes the Communist Party’s general secretary.

1924: Lenin dies; Stalin takes control of Russia.

The Marxist doctrine was refined and changed, especially after Marx’s death. Engels changed the revolutionary propaganda into a more peaceful patience and a quiet confidence of the evolutionary victory of a classless society. Under Vladimir Lenin, Marxism became more removed from the proletariat. According to Lenin, the workers could not organize their own revolt and needed leaders to plan and lead the revolution. Lenin also felt that revolution could and should occur in non–industrialized and non–capitalist nations. Lenin’s version of Marxism is commonly referred to as Marxism–Leninism. Joseph Stalin further altered Marxism to such a degree that it could barely even be called Marxism. His version, more so than Lenin’s, effectively destroyed the equality and freedom that Marxism was designed to promote.

HISTORY

Socialist and Utopian Beginnings

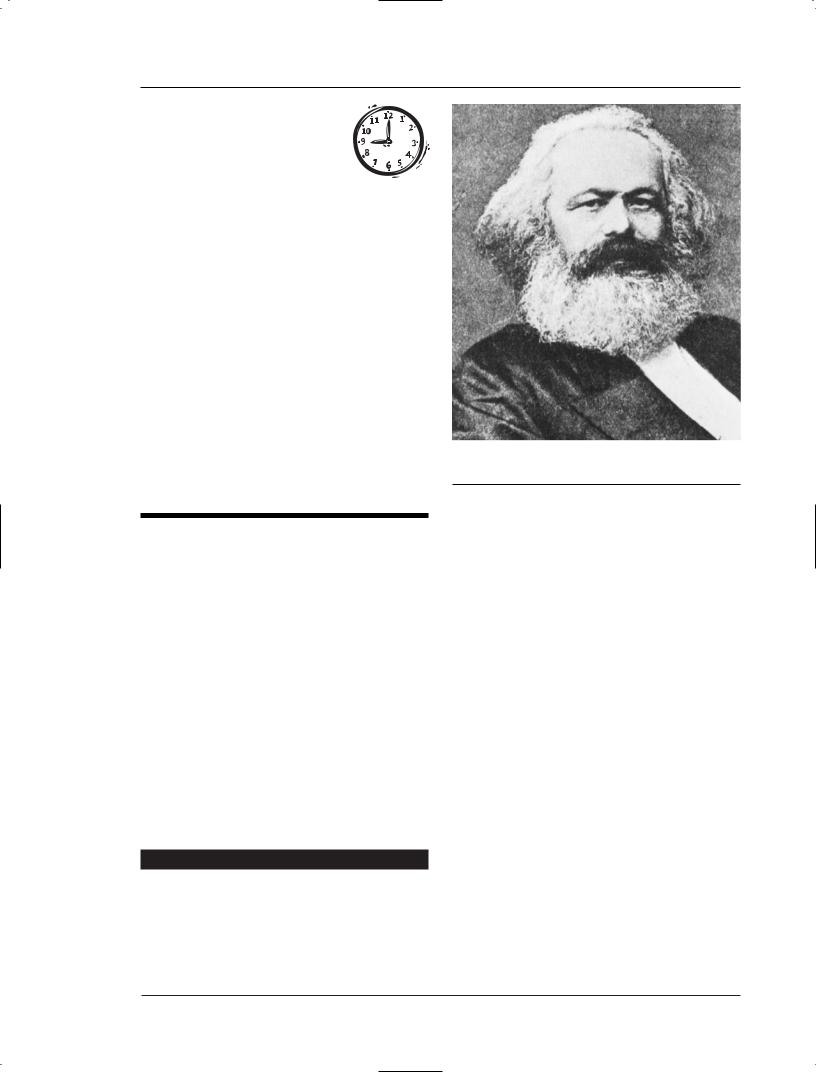

Socialism was labeled as such in the 1820s and has since been used by Karl Marx (1818–1883) and other philosophers to describe ways to organize society. Marxism stems from socialist and communist

Karl Marx.

ideas, though Marxism itself didn’t exist until the middle of the nineteenth century.

Socialists do not agree with capitalism, and believe competition between individuals breeds inequality. Cooperation is a better system to socialists, and a shared ownership of the forces of production and distribution will guarantee equality. Socialists feel that each member of society should have the same materials. Socialism does not necessarily dictate shared government, however, though some socialists are democrats.

Karl Marx was a socialist who molded some of his ideas from the ancient Greek philosopher Plato (428–348 B.C.). Plato wanted to begin a republic free of strife. He did not subscribe to democracy but rather felt that his republic should be run by “philoso- pher–kings,” trained individuals who made the rules for everyone else to obey. Plato felt that the personal interests of the population would not necessarily be helpful for the common good but would inhibit the de- cision–making process. People’s desires would block their judgment. Plato put community above all else.

Another socialist thinker was English statesman and author Sir Thomas More (1478–1535). He transferred the Greek word “utopia” to English to describe an island with an ideal society. The secret of the utopia’s success was socialism. All the wealth was shared, and poverty and crime did not exist. Rulers

2 1 2 |

P o l i t i c a l |

T h e o r i e s |

f o r |

S t u d e n t s |

M a r x i s m

BIOGRAPHY:

Karl Marx

Karl Marx was born May 5, 1818, in the Rhine province of Prussia (Germany). He was the oldest living son in a family of nine children. Both of his parents were Jewish but a year before Karl was born his father converted to the Evangelical Established Church. Young Karl was baptized when he was 6, though he was influenced more by the radical ideas of the Enlightenment than by religion. He was discriminated against because of his Jewish heritage, which may have begun his distaste for social inequality.

At the University of Berlin in 1836, Marx was introduced to George Hegel’s teachings and he began his association with the Young Hegelians. Hegel’s doctrines explained that when there were two ideas or desires in conflict, they would meet and form a third option better suited to both. The Young Hegelians moved toward atheism and political action and the Prussian government began to drive them from the universities.

After graduating in 1841, Marx began to contribute regularly to a newspaper in Cologne the following year. When he was the editor, the newspaper was suspended by the government soon after for its revolutionary ideas. In 1843 Marx married the daughter of a family friend, Jenny von Westphalen, and they moved to Paris. While there Marx began to associate with communist societies. He wrote The German– French Yearbooks, which did not prove very successful but created an alliance with Friedrich Engels which continued until Marx’s death. Marx was expelled from France and he and Engels went to Brussels in 1845. The two men collaborated closely after that.

The Communist League was formed in 1847 and Marx and Engels were asked to write its doctrine. A year later when it was completed, the League adopted it as their manifesto. The Communist Manifesto has become one of the most important documents written about economic theory and social history. It explains

that history is a series of struggles between the classes. It rejects social utopias and philosophical socialism centered around alienation. The Manifesto dictates 10 steps to communism, including progressive income tax and the abolition of inheritance.

In 1848 Marx was indicted for his writings and for advocating the nonpayment of taxes. He was acquitted, but banished from Paris. Marx went to London in 1849 and remained there for the rest of his life. He was frustrated by his failures on mainland Europe and rejoined the Communist League in London. He spent from 1850 to 1864 living in extreme poverty— Engels was supporting him financially—and relative seclusion. Several of his children died and his wife suffered breakdowns. The Marx family lived on scant means as Marx continued to write his theories.

In 1864, the International Working Men’s Association was founded. Marx wrote Das Kapital, which became the bible for the International. He was sought out to be a leader and organized various parties and ideas. The International flourished and intervened in union disputes.

After the Franco–German War in 1870, Marx slowly lost control of the International and it was disbanded in 1876. Marx’s energies waned and he experienced prolonged bouts of depression. He was still consulted on political matters but stayed largely removed. His wife died in 1881 and his eldest daughter in 1883. He died the following year.

Marx’s most famous work, Das Kapital, became known as the “Bible of the working class” by the International Working Men’s Association. The Communist Manifesto had similar weight as well, and despite Marx’s poverty and struggle, he had an enormous impact on the world. Despite the apparent failure of his theories, Marx’s writings remain some of the most influential ideas in human history.

were elected and there was freedom of belief. Farming, which More considered the least–favored work, was divided amongst everyone.

Two hundred years after More, Jean–Jacques Rousseau (1712–1788) created another idea of a perfect society in his works on political theory, most no-

tably The Social Contract. He felt that people were naturally good, and that society’s inequality drove evil into people. He agreed with More and Plato that community was the answer.

The French Revolution, in conjunction with the Industrial Revolution at the end of the eighteenth century

P o l i t i c a l |

T h e o r i e s |

f o r |

S t u d e n t s |

2 1 3 |

M a r x i s m

and the beginning of the nineteenth century, had profound effects on political thinking. Europe’s monarchy was brushed away and the privileges enjoyed by the clergy were invalidated. Liberty swept the land and equality became the battle cry. The populace realized that they had the power to alter the reality with which they were so unhappy. Though the Industrial Revolution was slow, it was unstoppable. Though the standard of living went up and there was more material to go around and less work needed to create it, work days for factory workers were seemingly endless and the conditions horrendous. Women and children worked for low wages and were easier to control than men. They often worked sixteen–hour shifts. Towns became crowded as people looked for work in the factories. Their needs, housing, and sanitation were ignored. Slums sprouted up everywhere. It was this poverty and dissatisfaction that made people begin to think that capitalism was not the best economic and political option.

Charles Fourier (1772–1837) felt that men were generally good and could therefore be organized into utopian societies. He envisioned communal units of 1,500 people per unit. The people would live in buildings called phalansteries, which he described in great detail. He also explained how the groups would relate to each other. Work would only be done a few hours per day, and children, who Fourier said enjoyed getting dirty, would do the unappetizing work that adults shunned. Fourier’s ideas influenced many socialist communities.

Another important socialist and utopian advocate was Robert Owen (1771–1858). Shocked by the working conditions in Britain (and himself the co–owner of a large spinning mill in Scotland), he began to form ideas of his own. In his mill, the work day was only 10 hours long. Children went to school instead of to work in the factories and his workers lived in houses and had sanitation and gardens. Owen still made money, despite his fair treatment of his workers. He began New Harmony, Indiana, as a utopian community but, like the other utopias, it didn’t last long— only from 1824 to 1828.

Marxist Developments

Marx’s ideas on socialism were so convincing that they spawned their own term: Marxism. Marx’s version of socialism not only explained the evolution of society but also examined the reasons for conflict within society. Marx grew up in Germany and was strongly influenced by his father and by his neighbor, Ludwig von Westphalen, an important political figure. Marx studied philosophy at the University of Berlin and joined the Young Hegelians, a group interested in the ideas of German philosopher George

Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel (1770–1831). The group was radical and revolutionary and, because of Marx’s affiliation with them and his political activity, he was unable to get a job in academia when he received his doctorate in 1841.

He turned to journalism to make his living and edited The Rhine Newspaper (Rheinische Zeitung), until the newspaper was shut down five months later for its liberal content. Marx and his wife moved to France where, in the midst of the revolution ideology, Marx developed his theories. Marx met Friedrich Engels (1820–1895) in Paris. Marx had many novel ideas but was less adept than Engels at explaining them in print. Engels had discovered England’s working class at his family’s factory in Manchester in 1842. He was already a communist and began his relationship with Karl Marx two years later in 1844. The two men wrote

The Holy Family and The German Ideology.

Marx’s writings were controversial. He wrote a great deal about the ills of his homeland and, in 1845, Germany convinced France to expel him. Marx moved to Brussels, Belgium. Engels went with him and the two joined a group called the Communist League. In 1847 the League asked them to create a statement about its beliefs, and Marx and Engels wrote The Communist Manifesto. The Manifesto got little immediate attention because of the Revolutions throughout Europe in 1848. Marx and Engels finally got to experience the revolution about which they’d been writing. When the French government fell, Marx went to Cologne, Germany, and became the editor of The New Rhine Newspaper (Neue Rheinische Zeitung). He was in Cologne when the workers rose up in Paris. Marx supported them enthusiastically in his newspaper, but after three days of fighting the workers were defeated. Marx was arrested in Cologne. During his trial, he made a speech about the conditions in Europe and, to the surprise of many, he was acquitted. Unable to jail him, the Prussian government expelled him again. The Marxes moved to London where they spent the remainder of their years.

Marx continued to write and was supported by Engels, who went to take over the management of his father’s Manchester cotton firm factory. Engels also contributed to Marx’s writing of Das Kapital, his critique of capitalism—the economic data and technical information comes from Engels. Engels also completed the second and third editions of Das Kapital after Marx’s death in 1883.

Marxist Decline and Revival

At that time, the industrial nations of Western Europe were in the middle of enormous social, economic,

2 1 4 |

P o l i t i c a l |

T h e o r i e s |

f o r |

S t u d e n t s |

M a r x i s m

MAJOR WRITINGS:

Das Kapital

Marx’s Das Kapital, first published in 1867, took him more than a quarter of a century to complete. It is an analysis of the free market economic system— the text is filled with comprehensive economic equations and hypothetical situations of workers in factories or on plantations. Marx felt that the capitalistic system created more and more wealth but was unable to use it wisely or spread it out equally. The flaws in the system exploited the masses, he said, and would continue to do so until the workers’ frustrations reached the breaking point. Marx frequently breaks out of the technical prose to lash out at what he sees as inequities in the capitalistic system or his theories on economic history:

One thing, however, is clear—nature does not produce on the one side owners of money or commodities, and on the other men possessing nothing but their own labour–power. This relation has no natural basis, neither is its social basis one that is common to all historical periods. It is clearly the result of a past historical development, the product of many economical revolutions, of the extinction of a whole series of older forms of social production. (Chapter VI).

Capital is dead labour, that vampire–like, only lives by sucking living labour, and lives the more, the more

labour it sucks. The time during which the labourer works is the time during which the capitalist consumes the labour–power he has purchased of him.

If the labourer consumes his disposable time for himself, he robs the capitalist.

The capitalist then takes his stand on the law of the exchange of commodities. He, like all other buyers, seeks to get the greatest possible benefit out of the use–value of his commodity. Suddenly the voice of the labourer, which had been stifled in the storm and stress of the process of production, rises. (Chapter X, Section 1).

In modern agriculture, as in the urban industries, the increased productiveness and quantity of labour set in motion are bought at the cost of laying waste and consuming by disease labour–power itself. Moreover, all progress in capitalistic agriculture is a progress in the art, not only of robbing the labourer, but of robbing the soil; all progress in increasing the fertility of the soil for a given time, is a progress towards ruining the lasting sources of that fertility. The more a country starts its development on the foundation of modern industry, like the United States, for example, the more rapid is this process of destruction. Capitalist production, therefore, develops technology, and the combining together of various processes into a social whole, only by sapping the original sources of all wealth—the soil and the labourer. (Chapter XV, Section 10).

and political change. The quality of education rose and population stabilized. Child labor began was discouraged, and the Western European countries began to look for colonies to further bolster their prosperity. This “imperialism” was in the name of trade and resources. Britain, France, and Germany claimed colonies in Africa, the Near East, and Asia.

This colonialization raised worker dissatisfaction. Not only did citizens have to fight in the colonial wars, but foreign investment meant that factories would be built abroad and that there would be no new jobs at home. At the same time, conditions had improved because of the capitalist systems. France, Germany, and England were becoming increasingly democratic, and labor unions formed in France by 1884. By 1900, there were 2 million union members in England, 850,000 in

Germany, and 250,000 in France. Political parties represented the working class in all three countries.

Socialism wasn’t dead, however. The German Social Democratic Party, a Marxist party, was formed in 1875. Marx hadn’t supported its ideology, which included state–controlled education. Marx had complained that the party’s platform didn’t look at the future. Socialist legislators were elected in Germany, however, despite the problems with the party.

Meanwhile, in England, the Labor Party had formed and had elected members to parliament. In Germany chancellor Otto von Bismarck (1815–1898) was trying to quiet the socialists by giving in to some of their demands. Social legislation was also passed in France and England and conditions in the factories improved.

P o l i t i c a l |

T h e o r i e s |

f o r |

S t u d e n t s |

2 1 5 |

M a r x i s m

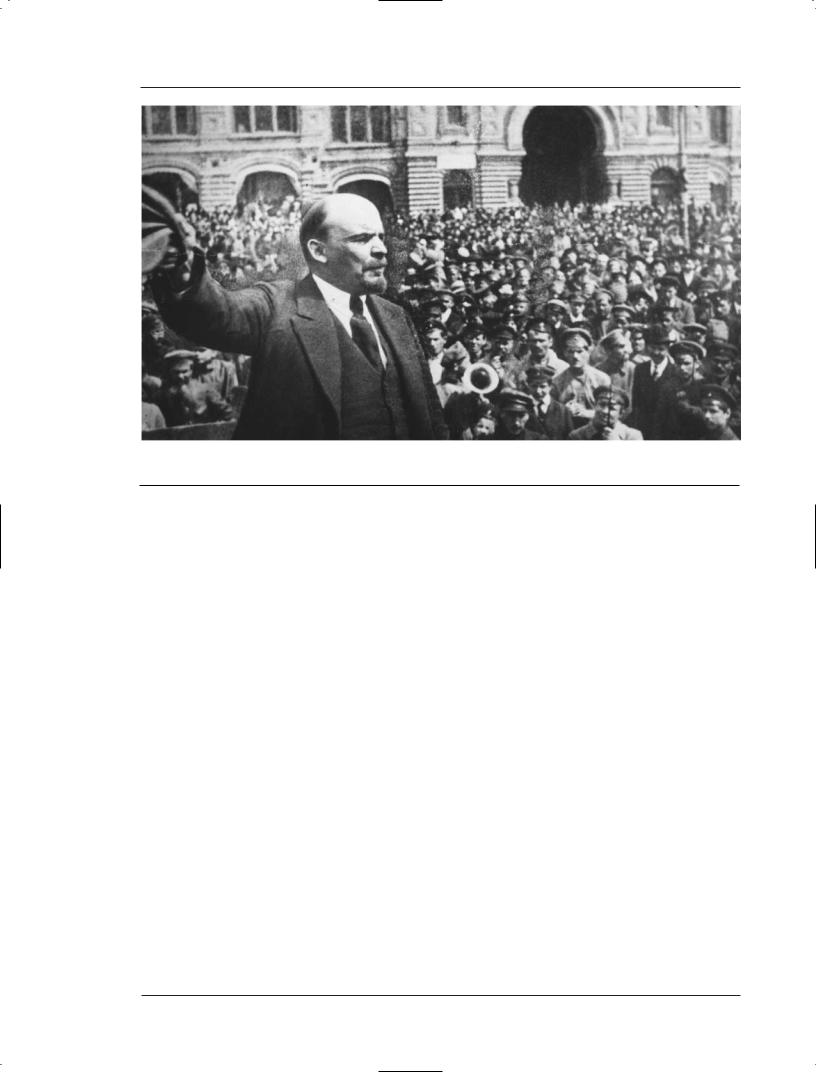

Vladimir Lenin, addressing a crowd of supporters in 1917. (Archive Photos, Inc.)

In the beginning of the twentieth century, England passed social insurance policies providing old age, sickness, and accident insurance. There was also a minimum wage law and unemployment insurance. If Marx had still been alive, he might have seen these successes as cause to alter his ideology. As things stood, Western Europe was moving away from revolutionary Marxism and concentrating on long–term reform. English Fabian Socialism (socialism based on slow change rather than revolution) overtook Marxism in its popularity because of its adherence to gradual social reform. There was skepticism surrounding Marxism, and after Engels’ death in 1895 there was no one left to defend its creation with equal authority.

The German Experience

In Germany, the Marxist Social Democratic party kept growing. The socialists there were dedicated to Marxism but they had trouble relating Marxist ideas to the already improving conditions under capitalism. Marxists split into two groups, the Orthodox Marxists and the Revisionists.

Karl Kautsky (1854–1938) was a leader of the Orthodox Marxists. He edited the New Times (Neue Zeit), a publication of the German Social Democratic party. He agreed with Marx’s economic arguments and centered on the problems with the lives of the working class. He felt that class struggle was evident because

of the impossibility of an agreement between the proletariat and the bourgeoisie. He ignored the idea of revolution, however, and argued that the working class could gain control peacefully.

Eduard Bernstein (1850–1932) wanted to update Marxism to address the improved conditions of the working class. He was a founder of Revisionism and he led the party in its abolition of the call for revolution. Bernstein claimed that the crisis inherent in capitalistic systems would become less frequent as capitalism developed and industry consolidated.

The Orthodox Marxists argued that the proletariat would revolt. They thought the workers would take control of the government, rather than overthrow it as Marx had dictated. They used peaceful methods to explain Marxism to the bourgeoisie to meet some of their goals. The Revisionists argued that Marxism was outdated. Both parties condemned violence and even the Orthodox Marxists were a muted version of what was envisioned by Karl Marx.

World War I brought more challenges to Marxism. A radical wing of the German Social Democratic party criticized the democracy used by the Orthodox and the Revisionist parties. Rosa Luxemburg (1870–1919) was unhappy with what the parties had done to Marxism. Luxemburg changed Marx’s ideas, stretching them to include a theory of imperialism. She looked at the European colonialization from an eco-

2 1 6 |

P o l i t i c a l |

T h e o r i e s |

f o r |

S t u d e n t s |

M a r x i s m

nomic standpoint and argued that colonialization was necessary for capitalistic countries to increase their markets. Without new markets they could not progress and if they could not progress, they would not reach socialism. She felt that when the available markets had been saturated, capitalism would collapse and socialism would sweep up the debris.

Luxemburg believed in Marxism’s class struggle theory. She fought for revolution and encouraged workers to strike and stifle whatever they could as practice for the final revolution that would overturn capitalism forever.

The defenders of Marxism were a loose selection of socialist groups that convened in congresses every three years. Marxism had been one of the competing socialist doctrines of the First International and the most respected during the Second International in 1889. The International reaffirmed the Marxist’s doctrines of class struggle and revolution. When World War I broke out in 1914, the socialist sector splintered and Marxism’s influence declined in Western Europe. At the same time, however, the Marxist Vladimir Lenin (1870–1924) was leading a revolt in Russia.

Marxism in Russia

Marx had dismissed Russia as being too backward to deal with, much as he had dismissed the peasants as being too backward to take control. In 1917 Tsar Nicholas II was ousted and a Provisional Government was put in his place. Soon after that, the Bolsheviks and Marxist-Leninists took over the government. Lenin began to mold Marxism to his methods. He kept Marx’s ideas of revolution and, for the first time, began to implement Marxist ideology.

Lenin had to bend Marxism quite a bit to fit it into Russia. Lenin understood that in Russia the working class was too small to revolt on its own. He gathered the support of the peasantry by turning the land over to the peasants and was rewarded with their support. He talked about common interests and he altered the nature of Marxist revolution. While Marx had felt that revolution would be spontaneous, Lenin felt that the workers only wanted to improve their working conditions and their wages and that this was not enough to create a revolution. He felt that they needed to be led by revolutionaries who would take control, and he felt that the proletariat would not be equipped to handle the power if they got it on their own through revolution.

Marx had described a proletariat dictatorship as a government directly created after revolution with the purpose of bringing in a communist society. Lenin called his beliefs Marxism and considered himself a

Marxist despite his alterations. Lenin felt that a party–controlled government was essential to success and, once in power, he suppressed opposition and silenced objectors in the name of achieving socialism. Instead of the freedom and creativity that Marxism predicted, Lenin’s reality was a repression and lack of equality that was only exaggerated by his successor, Joseph Stalin (1879–1953). Russia under Stalin could no longer be referred to as Marxist; communism, or more specifically, a harsh form later named Stalinism, took its place.

THEORY IN DEPTH

Marxism is a political theory and a means of achieving that theory. Karl Marx developed Marxism in the nineteenth century. He was unhappy with capitalism and felt a need for a new order. He drew his ideas from studies of industrial revolutions, from the ideas of the German philosopher George Hegel, from the European Enlightenment, and from a commitment to social equality and justice. Marxism is centered around the idea of social change and revolution to overthrow the capitalistic injustices heaped upon the common man. It covers three areas: philosophy, history, and economics.

Philosophy

Philosophically, Marxism studies the human mind. It examines the method by which man defines himself and how he decides what is real and what is not. Marx felt that ideas and practices were never fixed but were rather in a state of constant evolution based upon the surroundings at the time. He agreed with his early mentor, Hegel, who felt that change came through two opposing forces which struck each other and through their contact created a third entity. Hegel called this the “synthesis.” The two opposing forces which created the synthesis were the “thesis” and the “antithesis.” In time, the synthesis becomes a thesis with its own antithesis and, through a collision, creates another synthesis.

Though Hegel’s notion of continual change gave Marx a framework, Marx wasn’t fully satisfied with it. Hegel felt that change resulted from “world spirit,” and that this spirit developed freedom. Marx felt that such vague notions made no sense. He believed that people controlled their own future. He rejected the idea that the spiritual world held importance and wanted to bring things back to earth. He applied Hegel’s spiritual metaphors to the physical world, which he found much more practical, viable, and believable.

P o l i t i c a l |

T h e o r i e s |

f o r |

S t u d e n t s |

2 1 7 |

M a r x i s m

Marx also declared that philosophy had to become real. It was not enough to observe and comment on the world—one must try to change it and to make it better. Marx thought that knowledge centered around an analysis of ideas and that, without taking the next step to action, things became stymied. He looked at each problem in relation to others and then related them in turn to economic and political realities.

Marx’s philosophy on the causes of revolution was unlike most prominent thinkers of his time. In the nineteenth century, major historical events such as revolution were usually explained in terms of great and dynamic leaders or religious figures. Marx sought to explain revolution in economic terms. He stated that when technological improvements are made in society, the power structure impedes that technology from being used in the best way. In the case of capitalism, Marx thought that its rules of private property ownership would stand in the way of the developing technology that was greatly increasing the production of goods and services.

This theory did have a historical precedent—dur- ing the Middle Ages, when technological progress in society was a leading factor in the demise of feudalism and the birth of capitalism. Centuries later, the advancements of the Industrial Revolution would lead, according to Marx, to the only possible outcome: the destruction of capitalism by violent revolution. As Today’s Isms states: “Marx could find no instance in history in which a major social and economic system freely abdicated to its successor. On the assumption that the future will resemble the past, the communists, as the Communist Manifesto says, ‘openly declare that their ends can be attained only by the forcible overthrow of all existing social conditions.’ This is a crucial tenet of Marxism–Leninism, and one that clearly distinguishes it from democracy.”

History

Marxism also examines history. It explains that history is a series of conflicts and arrangements of social arenas. Labor helps to define the social groups. The way in which people labor with the tools available and the groups in which they operate are what defines the different sections of history. Marx labels five historical chapters in the way labor is conducted: the slave state, feudalism, capitalism, socialism, and finally, Marxism. He argues that capitalism exploits the workers in the same way that the slave state does and, for this reason, cannot last. The inequalities of capitalism will lead to revolution to equalize resources. Socialism will ensue, and after the wrinkles are ironed out of socialism, Marxism will replace it.

Marx felt that history could only be explained in terms of what people had done in, and to, the material world. The pattern was the same as Hegel’s thesis, antithesis, and synthesis. Continual conflict created new items to create new conflict, and so on.

Marx also said that every society had a “superstructure.” This structure was comprised of the religious beliefs, laws and customs, and the political institutions and ideas. The superstructure protected the upper classes more than the lower. Religion, for example, would teach the poor that it was a virtue to live in poverty and to concentrate on the afterlife rather than on the life being lived at the moment. The poor would therefore not have a good reason to object to their condition, given the explanation of its worth.

Marx talked at length about this class struggle and the barriers it created. He felt that change was inevitable, and that the lower class would eventually reach a breaking point at which they would revolt to improve their condition.

It was this sort of class struggle, according to Marx, that would bring societal change. Mankind has traveled through history this way, from the phases of slavery to feudalism to capitalism. When farming took over hunting and gathering, a more distinct superstructure was necessary. When feudalism followed slavery, serfs with their increased freedom created a new class, the bourgeoisie. Eventually, this group overthrew the feudal lords and capitalism swept in.

Economics

Marxism’s main focus is economics. Marx’s program for man begins with satisfying one’s needs. Men need to satisfy certain needs such as food and shelter. Their means of achieving this are a struggle with nature. Hunting and building disturb nature. Through this disruption, man finds himself human because of his own labor. At the same time, he appreciates his mastery of nature. Born in nature, man becomes human, ironically, by fighting nature. Marx contends that all of history is the struggle between man and nature through his labor. Man is self–sufficient and free only when he manipulates the nature that created him.

Capitalism, Marx believed, stole freedom. Marx dissects capitalism to explain its inadequacies. A laborer is paid for the work he does, for example, but is paid an amount to allow him to support his family rather than an amount based on the profit he has given his employer. The laborer is separated, alienated, from his product. This destroys his freedom. The capitalists profit enormously, according to Marx, while the workers make a subsistence living regardless of the worth of their creations. Workers are not paid according to

2 1 8 |

P o l i t i c a l |

T h e o r i e s |

f o r |

S t u d e n t s |

M a r x i s m

their value, and this injustice will lead to dissatisfaction and the collapse of capitalism. Since there is a lack of freedom, capitalism is not a viable long–term option.

The workers are a class of their own, the proletariat, while the owners of production are a higher class, the capitalists. There is middle class, the bourgeoisie, who don’t labor in the same way as the proletariat but rather organize the labor and work from offices to direct and manage the factories. Marxism dictates that the struggle between the capitalists and the proletariat will end in socialism. Socialism will be the synthesis of the thesis and antithesis of the proletariat and the capitalist.

The most important thing about any society, Marx said, is the way in which it provides for itself. Its economic means, for example, could include hunting and gathering or factories and grocery stores. Marx called these methods a society’s modes of production. The modes of production could be very simple or infinitely complicated, depending on the society. The means of production were the tools the society used to satisfy its needs, such as knives and spears or machinery and computers.

The relations of production were the owners of the means of production. The capitalists, the village chiefs, the monarchs, or the elders could be the relations of production. The relations of production were either owned by society as a whole or were privately owned by individuals. Marx felt that private property allowed inequality and provided a way to create different classes—a small upper–class that had almost everything and a large lower class with virtually nothing to sustain itself.

Marxism identifies “alienation” as a central problem with capitalism. Since labor isn’t directly related to its value, it is alienated labor. The worker is also alienated from himself because he is selling his labor and has become a commodity. He is further alienated by specialization. His task becomes so minute that he can perform it very quickly which speeds up production, but his expertise is so limited that he is virtually useless. Adam Smith (1723–1790), the “father of capitalism,” argued that such specialization, though marvelous for capitalists, rendered the worker worthless in any real measure. The worker is then alienated from his humanness. It is this alienation, in addition to exploitation of the workers by the capitalists, which form the contradictions that will disband capitalism.

Marx goes on to say that private property becomes a principal means of alienating oneself. It is this private ownership that separates one from the collective and creates individual existences separate from the whole.

The economic alienation is coupled with a political alienation. The capitalistic society of the bourgeoisie is separated into economics and politics. Marx viewed the political arena as the vessel for separating the classes and for allowing one class to dominate the next.

The market Marx analyzed the market system in depth in his Das Kapital. He studied the economy wholly rather than in parts. His ideas center on the belief that economic value comes directly from human labor. Marx felt that capitalism would develop to include more and more contradictions. The inequality of the laborer’s pay versus the capitalist’s profit was the first contradiction. In addition, technology invites trouble. A machine will allow a capitalist to produce more at a lower cost, but competition keeps him from realizing more gain. He must keep up with the latest machinery to remain competitive, which means transferring money once designated for workers and applying them to technology instead. As a result, his rate of profit declines.

The market will also be shaken by crisis periodically. This instability creates increasing poverty, as people are not able to keep up with the fluctuating market. The separation of the proletariat and the capitalists increases and the classes are even more distinct. The monetary assets are controlled by fewer and fewer people and what remains is shared by more and more.

Class struggle Marx also explains how the worker’s position will lead to revolution. One thing the working class will gain is knowledge about group activity. The factory workers learn to work cooperatively and will eventually see that they can channel this cooperative effort into a movement to better their condition. This is what Marx calls class consciousness. The realization of one’s condition will lead to a greater understanding and, in turn, to conflict between the classes. Pressures build and the workers begin to demand change.

Marx spoke at great length about this class struggle, which is the focal point of his social evolution. When man is conscious of his alienation, he will move toward revolution. This will be the beginning of communism. There are two forms of revolution for Marx. The first is a standard uprising of the proletariat after having been exploited past their breaking point. The second type of revolution is more permanent—a provisional merger between proletariat and bourgeoisie rebelling, together, against capitalism. Later on, when there is a proletariat majority to the coalition, power

P o l i t i c a l |

T h e o r i e s |

f o r |

S t u d e n t s |

2 1 9 |

M a r x i s m

BIOGRAPHY:

Friedrich Engels

Friedrich Engels was born on November 28, 1820, in the Rhine province of Prussia (Germany). He was a friend and colleague of Karl Marx and the co–author of the Communist Manifesto, which became the bible of the Communist Party.

Engels grew up in a liberal family of Protestants loyal to Prussia. His father owned a textile factory in Bremen and expected Engels to be a part of the family business. Because of this, Engels led a double life.

When Engels was 18 he began work with his father. During working hours, Engels was an apprentice and an athlete. He also studied language. After hours, however, he read revolutionary works and became interested in the Young Hegelians, leftists following the ideas of the philosopher George Hegel, who asserted that progress and change come from opposing views that, when they clash, form a new ideology. The Young Hegelians were trying to accelerate the process by denouncing all things they found oppressive.

In 1841, Engels returned to Bremen and enlisted in an artillery regiment in Berlin. He frequented university lectures, though he wasn’t enrolled, and the articles he’d written got him accepted into the Young Hegelian group of “The Free.” After he finished his service a year later, Engels met Moses Hess. It was Hess who sparked his interest in communism, explaining that the consequence of the Hegelian idea was communism.

In 1842 Engels went to Manchester, England, to help with his father’s partnership in a cotton plant. He

continued to live his double life, writing communist articles after hours and meeting radical personalities.

Engels laid out an early form of scientific socialism in two articles he wrote for the “German–French Yearbooks.” He found contradictions in liberal economics and felt that private property ownership created a chasm between the rich and the poor. By then Engels had begun to collaborate with Karl Marx, whom he’d met in France. Their first joint work was The German Ideology, which denounced those who didn’t support revolution. Marx had formed a notion, which Engels endorsed, of history which ended, necessarily, in communism.

The Communist League held its first congress in 1847. At the second congress, Marx and Engels drafted the communist principles to which the League would subscribe. This Communist Manifesto became the bible to the Communist League.

Though Marx was the central creator of Marxism, Engels was his specialist on questions of the military, international affairs, science, nationality, and economics. It was Engels who sold Das Kapital with his review of the book. When Marx died in 1883, Engels became the central Marxist figure. He finished volumes two and three of Das Kapital from Marx’s notes and manuscripts.

Engels developed cancer and died at the age of 75 in 1895 in London, England. With Marx, he helped to create Marxism and to shape the communist views that would later be used (and abused) by Vladimir Lenin and Joseph Stalin in Soviet Russia.

is transferred completely to the proletariat. It was this revolution that would bring capitalism to an end and allow socialism and, finally, Marxism, to take its place. After the establishment of a Marxist economy, class structure would disappear from society.

Engels’ View

Friedrich Engels, Marx’s friend and the co–au- thor of The Communist Manifesto, added his comments to Marx’s capitalism critique. Engels felt that man’s mentality could be its own prison. Ideologies allowed people to understand themselves and where they fit into the puzzle. These ideas masked the true

picture, their exploitation. Ideologically, for example, the capitalist will give the workers the impression that he is working in their best interest. The workers will feel that, though they are paid small sums, they are appreciated and cared for. But in reality, the capitalist will simply be spouting words to boost morale and encourage loyalty, so that he can continue to get as much labor from his workers as possible, and for the lowest price. According to Engels, workers focus on the ways in which they are not exploited rather than on all the ways in which they are.

In addition to the Marxism drawn out by Mark and Engels, there is Soviet Marxism. It is debatable

2 2 0 |

P o l i t i c a l |

T h e o r i e s |

f o r |

S t u d e n t s |

M a r x i s m

as to whether or not the version of Marxism practiced by Vladimir Lenin in Russia was still true Marxism or whether it was so distorted that it became something else entirely.

would be read because of its difficult style). The first Russian Marxist group, The Liberation of Labor, was formed in 1883. The Russian Marxists were a small minority and the majority of the socialists didn’t subscribe to Marx’s call for world revolution.

THEORY IN ACTION

When Marx and Engels died at the end of the nineteenth century, Marxism’s evolution was inherited by the revolutionaries of the next generation. In Western Europe at that time, conditions improved for factory workers. Economic prosperity meant improved living standards across the board. Workers formed unions and were able to negotiate better working conditions and earnings. Many European countries were becoming more democratic, moving away from Marxism, and were prospering.

In Western Europe the people felt satisfied and, rather than jeopardizing what they’d gained by having a revolution, they worked to gradually improve their conditions. Marxism fizzled into smaller groups of intellectuals who, in order to gain any support at all, stressed reform in place of revolution.

When the Second International was formed as the latest communist entity, it was an international organization of socialist parties. Its members slowly lost their revolutionary spirit in favor of long–term reform. Democratic socialist writer Eduard Bernstein said that capitalism was making life better, not worse. He pointed out that violent struggles between the classes was not the best way to create change. Capitalism would gradually evolve into socialism, he said. His ideas were called revisionism and were considered an updated version of Marxism. The Second International went along with his ideas.

While Marxism was shrinking away in Western Europe, it was spreading into Russia and gaining momentum. Much of Russia’s population was poor. The majority were peasants who had been liberated from serfdom and slavery by Tsar Alexander II (1818– 1881) in 1861 but who lived in the same conditions they had before their freedom. Though Russia was also going through an industrial revolution, it was far behind Europe. To make matters worse, the tsar had almost complete power over his people. There was a huge class difference between the minute elite and the uneducated mass peasant population. The groups did- n’t interact at all. Ironically, most of the revolutionaries were from the elite class and knew little of the life of the people for whom they were concerned.

Das Kapital was translated into Russian in the 1870s (ironically, the tsarist censors didn’t think it

Marxism Under Lenin

Vladimir Lenin was born in 1870. He grew up in a middle class family and had a happy childhood. During his adolescence, however, two significant things happened that helped lead him down the road to professional revolutionary. When Lenin was 16 his father, a schoolteacher, died of a stroke; the following year his brother was hanged for being involved in a revolutionary plot to kill the tsar.

Lenin was expelled from the university he was attending for participated in a student protest. Studying from home he learned about revolutionary leaders and read Das Kapital. Lenin became one of the most important leaders of Russian Marxism and spent the next 17 years helping the communists gather momentum. He became a Marxist in the 1890s, taking some of his ideas from Marxism and combining them with Russian revolutionary tradition. His version of Marxism is commonly known as Leninism or Marxism–Leninism.

Lenin’s ideas Lenin did not agree with Marx’s assumption that a society must pass through capitalism before it reaches socialism. Lenin desperately wanted socialism. He did not want to wait for Russia to go through capitalism—he wanted change to happen quickly, so he organized a political party. In keeping with Russian socialist tradition, Lenin distrusted the masses. The masses, at the time, wanted the Marxist party to be modeled after the German Social Democratic Party. Lenin, however, felt that the party workers would be happy with minor changes and would ignore the need for revolution. They would not reach “revolutionary consciousness,” Lenin said. He organized his ideas in a pamphlet published in 1902 called What Is to Be Done? named in honor of a book written by Nicholas Chernyshevsky (1828–1889), a Russian revolutionary.

Lenin felt that a group of professional revolutionaries should be in control of the revolution. This group would make the decisions instead of the proletariat. Decisions would be made by the leaders, the central committee. Policy could be debated but when a decision was reached, it was to be followed. In addition, Lenin’s party was to be kept secret to avoid censorship by the government.

This party model was also taken from Chernyshevsky’s book. Many of the Marxists in Russia did

P o l i t i c a l |

T h e o r i e s |

f o r |

S t u d e n t s |

2 2 1 |