Political Theories for Students

.pdf

M a r x i s m

not agree with Lenin’s party ideas and thought that the central committee would become a dictatorship. This argument led to a split in the Russian Social Democratic Party the next year. The two sections were called the Bolsheviks (the majority) led by Lenin, and the Mensheviks (the minority). Leon Trotsky (1879–1940), a young revolutionary who grew to enormous power in the party, criticized Lenin’s ideas. He said that Lenin’s party would substitute itself for the proletariat, the central committee would substitute itself for the party, and the dictator who took control would substitute himself for the central committee. Many years later, Trotsky ignored his own words and became a Bolshevik, helping to bring them to power.

Lenin also changed another aspect of Marxism. Marxist analysis predicted that the first countries to overthrow their governments and their capitalistic economies would be the most economically advanced, by definition of having to first evolve through capitalism. That meant that Western Europe would have to do it first, given its relative economic success. Lenin didn’t see any evidence of revolutionary ideology in the West and therefore couldn’t accept Marx’s prediction. Lenin argued that when Marx wrote Das Kapital, capitalism had not yet become worldwide. Since Marx’s death, capitalism had swept the planet and had led to exploitation of Asia and Africa. Lenin called this exploitation “imperialism.” He said that imperialism had good points and bad points. One bad point was that the socialist revolution would be put off in the capitalist countries because they were able to boost the living conditions of their proletariat from the goods they’d exploited from Africa and Asia. One good point was that the capitalist–imperialist system had an Achilles’ heel. Russia’s capitalism was much less steady and could, therefore, be the first to collapse— a direct reversal of Marxist theory. This revolution would then spread in reverse order from Marx’s theory, going from the lesser advanced countries to the more advanced.

Lenin felt that his revolutionaries should use any means necessary to overthrow capitalist Russia. Before the Bolsheviks seized control in 1917, Lenin endorsed extortion, fraud, robbery, and other crimes. After he came to power he seemed willing to do anything to keep it. This belief allowed him to commit heinous acts of cruelty to try to create a society that would put an end to such cruelty forever.

Revolution in 1905 Until 1904, the Marxist leaders and Russian revolutionaries remained in exile and were unable to unseat the tsar. In 1904, Russia went to war with Japan. The tsar, Nicholas II, thought it would be easy to defeat the Japanese, but the war

proved to be disastrous. Conditions worsened in Russia. There was a revolution in 1905, which began with peaceful demonstrations but ended in massacre by the tsar’s troops. As the revolution spread to the Russian capital of Moscow, Lenin returned to Russia from Europe to lead the Bolsheviks, and Leon Trotsky led a strike against the government.

After the failed revolt, Lenin was forced into exile from 1907 until 1917 and, from a distance, struggled to keep the Bolsheviks united. To this end he organized the Bolshevik Party Conference in Prague in 1912, which officially separated the Mensheviks from the Bolsheviks.

Through their experiences, the Bolsheviks and the Mensheviks learned separate lessons. The Mensheviks decided that the proletariat was too small for a revolution and that capitalism had to mature before the proletariat would be in the majority. The Bolsheviks felt that waiting for capitalism to mature was a waste of time. Lenin looked for ways to increase the proletariat’s numbers. He decided to try to ally the peasantry with the proletariat. The peasantry wouldn’t hold any decision–making power, but their numbers alone would be useful. Lenin decided that he could win the peasants by giving them a few of their demands. Karl Marx had argued that the peasants were a warped class, but Lenin needed them for his program to have enough support for an uprising to succeed.

Although the 1905 revolution failed, Nicholas II was pressured to make changes. He created a constitution and made some steps toward ensuring the people had civil rights, at least on paper. Russia had its first parliament, the Duma. The Duma had limited power that catered to the upper class but was a step toward democracy. The government also tried to raise the peasantry’s standard of living, improve the army, create opportunities for education, and bolster the industrial revolution. However, despite the changes, the majority of the population remained very poor and the upper classes were displeased with the weak nature of the reforms.

Changes in Russia World War I began in 1914. Russia, France, and England fought against Austria–Hun- gary and Germany. From the onset of the fighting, Russia suffered crippling defeats. The national pride the country felt when the troops first marched off to war quickly faded. Marches and riots swept the country. Workers and soldiers turned against the tsar, and Nicholas II was forced out in March 1917. The 300–year–old Romanov Dynasty was thrown away, and a Provisional Government composed of leaders of the Duma and noblemen was swept into place.

2 2 2 |

P o l i t i c a l |

T h e o r i e s |

f o r |

S t u d e n t s |

M a r x i s m

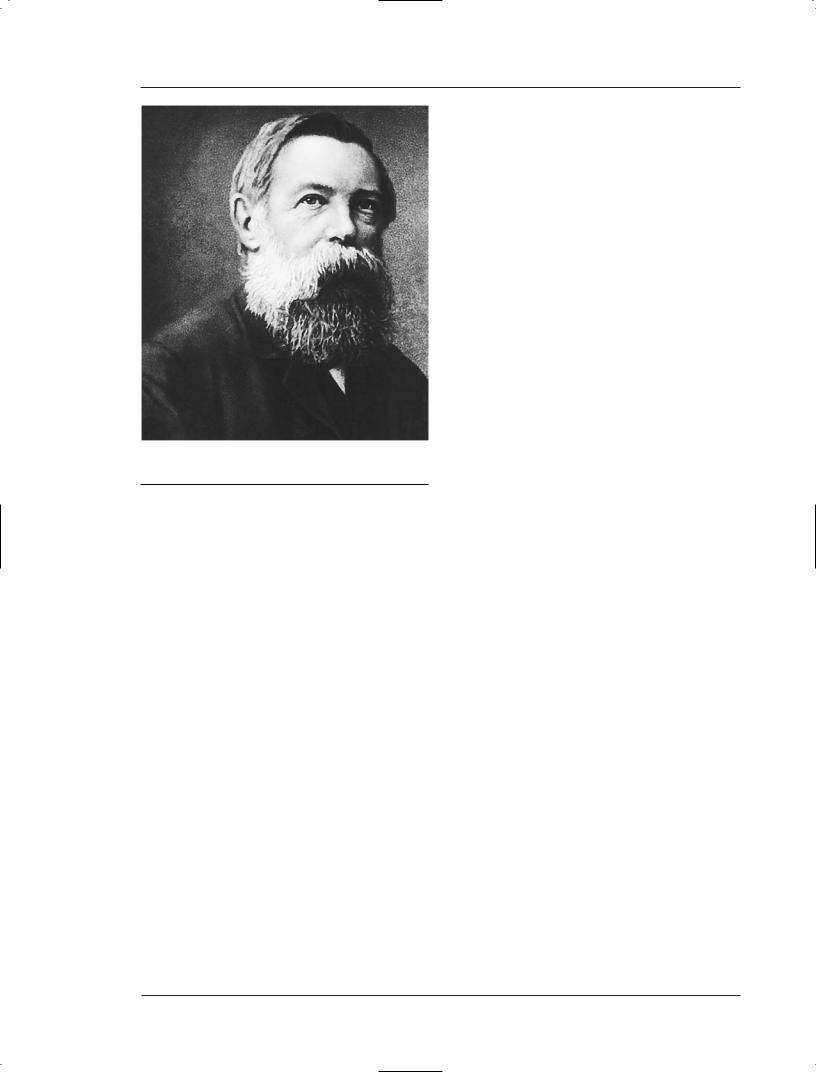

BIOGRAPHY:

Vladimir Lenin

Vladimir Lenin was born April 10, 1870, in Simbirsk, Russia. The founder of the Russian Communist Party, also known as the Bolsheviks, he altered Marxism and formed his own brand of political theory which is commonly called Marxism–Leninism or Leninism.

Lenin was the third of six well–educated children. He was academically successful at a young age and graduated first in his class in high school. Very adept in Greek and Latin, he seemed to be on the road to becoming a professional academic. When he was 16, however, he began to rebel. Along with his siblings, he joined the revolutionary movement to improve the political and civil rights of Russia’s citizens.

Lenin’s father died after having been threatened by the government while Lenin was still an adolescent. Soon after his father’s death, his older brother was hanged for associating with a terrorist group. These two events may have cemented Lenin’s feelings against the government and paved the way for his future success as a revolutionary.

In 1887 Lenin enrolled in Kazan University to study law and Marxism. He became a Marxist in 1889 and passed his law examinations in 1891. He was a practicing lawyer from 1892 to 1893 who served peasants and artisans, helping the poor rather than the rich. He developed a hatred for the legal system’s tendency to favor the wealthy and, in turn, he began to hate lawyers.

Lenin moved to St. Petersburg in 1893 and began to broaden his Marxist associations while working as a public defender. He was sent to meet Russian exiles in 1895. When he returned, he and his Marxist comrades created the Union for the Struggle for the Liberation of the Working Class to unify the Marxist factions. The Union supported the working class, strikes, helped with their education and published information on Marxism. Lenin was thrown in jail for 15 months and afterward was sent to Siberia in exile.

Upon his return to Russia in 1900, Lenin began to build support for his ideas. Marxists were a small minority and to create a revolution that would overthrow the government, Lenin needed to have a majority. Many Russians supported the Populists, who believed that Russia was in the midst of capitalism and that it needed to remain capitalistic to reach its perfection until everyone had reached a high economic level at which point socialism would naturally ensue.

Lenin disagreed, arguing that even if land was divided and properties shared it would not be socialism but rather would be a different type of capitalism. Lenin felt that Marxism was the only way to socialism. He wrote What is to be Done? in 1902, outlining the problems with capitalism and the virtues of socialism.

By 1921 Lenin had crushed all opposition parties arguing that they did not support the Soviet cause. Many of the peasants and members of the working class had become disenchanted with Lenin’s government. The party became overrun with incompetence and even the agency responsible for promoting organization, run by Joseph Stalin, was very inefficient. In 1922, Stalin became the general secretary of the party and consolidated his power. Lenin was frustrated that Russia was so far from his portrait of Socialism in his State and Revolution. He fell ill that spring and never fully recovered. Lenin continued to have episodes of sickness and, though he still wrote socialist propaganda, he never returned to the leadership position. He dictated a series of articles called the “Testament” centering on his fears of instability of the government with dominating people such as Trotsky and Stalin. He died of his third stroke on January 21, 1924. British Prime Minister Winston Churchill later wrote that the Russian people’s worst misfortune was Lenin’s birth; their next worst, Lenin’s death.

The Provisional Government planned to create a democracy like those in the West. They wanted to promote capitalism and reform instead of revolution. The government enacted laws expanding civil rights and shortening the work day to eight hours. They freed po-

litical prisoners and planned for a national election. But it wasn’t enough.

Russia was still in the war, and the Provisional Government’s popularity cascaded downward. Lenin returned to Russia from exile in Europe the same year,

P o l i t i c a l |

T h e o r i e s |

f o r |

S t u d e n t s |

2 2 3 |

M a r x i s m

arriving in Petrograd (formerly St. Petersburg) on April 16, 1917. Lenin was determined to overthrow the Provisional Government believing he was the only one who could lead Russia into socialism. He denounced this government as imperialistic despite its claims of democracy.

The Bolsheviks revolt By the autumn of 1917, the Bolsheviks were the majority party and Lenin decided to make his move. Though many of his supporters wanted the Provisional Government replaced by a coalition of the major parties, Lenin convinced them that a dictatorship of one party would be better. Trotsky helped Lenin to win support and, in October, Lenin’s central committee voted to overthrow the government.

The Bolshevik militia, called the Red Guards, deposed the Provisional Government in the first week of November 1917, by seizing important areas in Petrograd and arresting the ministers of the Provisional Government. The takeover was easy and smooth, and much of Russia missed it entirely. In a day, with a relatively small death toll of several hundred, the Russian democratic experiment had ended. The world’s first attempt at Marxism had begun, with Lenin at its helm.

The Bolsheviks initially controlled only Petrograd and the surrounding countryside, but Lenin wanted more. He did two things to increase his popularity and control. He gave Russia’s farmland to the peasants to win their support, and he began negotiations to end the war. The Treaty of Brest–Litovsk, signed by Germany in 1918, gave Russia freedom from the war in exchange for territory—territory, Lenin knew, Russia would get back someday.

The next step for the Bolsheviks was to exterminate their rivals. Lenin met opposition when he fought to make Bolshevik control over the government absolute. He finally allowed a tiny minority party to have a small voice, but after a few months even that was quashed and control became entirely Bolshevik.

Newspapers that were not socialist were shut down and Lenin’s secret police, the Cheka, infiltrated the population and eliminated opposition to their leadership. In 1918 the Bolsheviks got rid of the Constituent Assembly which had been elected the year before.

Lenin’s repression of opposition led to civil war. The fighting lasted until 1920. Virtually everyone who was not Bolshevik, or The Reds, was fighting against them. The Whites, or anti–Bolsheviks, were supported by Britain, the United States, and France.

By using savage and bloody tactics, the Bolsheviks eventually won the civil war. They created the

first concentration camps in history to house their political prisoners. The Cheka crushed worker strikes and stole food from anyone who had it, forcing peasants to give up their grain.

The Bolsheviks seized food, controlled the factories, forbid trade, forced labor, and crushed dissension. These policies killed the Russian economy but supplied the Red Army with food and supplies which was, in Lenin’s view, crucial.

When the civil war ended, the Bolsheviks’ power was shaky. The economy had been flattened, riots and strikes flooded the cities, and a massive famine killed 5 million people from 1921 to 1922. In response, the Bolsheviks met for their Tenth Party Congress to discuss how to bolster the economy and the Bolshevik’s popularity. Lenin suggested an end to the war communism that had confiscated provisions from the peasants. He created the New Economic Policy, designed feed his starving country. It allowed farmers to sell their goods while paying the government a percentage of their profits in tax. Peasants who had lost their incentive to grow crops began to replant. After two years, the country began to feed itself again.

Trouble within the party Many of the Bolsheviks were frustrated by this provision, however, because it stank of capitalism. The war communism, which confiscated goods from the peasants and distributed them among the troops, had been a step toward socialism, and had already failed.

The New Economic Policy created another problem. According to Marxism, in order to achieve socialism the industrial revolution had to continue until it reached modernity. The economic policy didn’t have the resources for this, however, and the industries controlled by the state were too inefficient to amass the profits needed to invest in technology, nor could the taxes be raised without killing the incentives for peasants to produce food. Moreover, Lenin believed the New Economic Policy would relieve the peasants’ fears and ease the transition to communism.

The Bolsheviks were also in the midst of a political struggle. During the civil war the opposition to the Reds had been violently silenced leading to resentment and dissatisfaction with the Bolsheviks. At the Tenth Party Congress that accepted Lenin’s New Economic Policy, the leaders of the Congress created the post of general secretary to organize the party’s regime, giving the post to Joseph (Dzhugashvili) Stalin.

Lenin had not expected party corruption, as it was not in keeping with Marxism. However, the party was overrun with it during the 1920s and officials used their power to satisfy personal whims. Lenin was very

2 2 4 |

P o l i t i c a l |

T h e o r i e s |

f o r |

S t u d e n t s |

M a r x i s m

worried that Stalin was involved in this corruption. Stalin used his title to acquire power and Lenin decided that Stalin should be replaced. Before he could advocate his position, however, Lenin suffered the first of his three strokes. He was confined to his bed for a year and died of his third stroke in 1924.

After Lenin died, his version of Marxism became called Leninism or Marxism–Leninism. Lenin had warped many of the ideas of Marxism to rationalize revolution in Russia and his dictatorship. His version was very different from that of Marx and Engels, and even more distant from the moderate reform sector of Marxism that had swept through Western Europe.

ANALYSIS AND CRITICAL RESPONSE

As with so many other political systems, Marxism in practice didn’t work exactly as it did in theory. Marx and Engels assumed that corruption wouldn’t be a problem under communism and that the negative vices and traits that caused such corruption were spawned from the inequality and dissatisfaction of capitalism. Since Marxism would provide for all, there would be no dissatisfaction and, therefore, no reason for criminal activity. Perhaps it is impossible to say if this would be the case, as a true Marxist state has never really been reached.

There has not been a Marxist success without simultaneous abuses by those in power. Marx’s ideas have been called idealistic. It is utopian, to use Marx’s own word, to believe that a society can exist without a class struggle of some kind. It was unrealistic to expect that work would be done voluntarily, crime would not exist, political and religious differences would be forgotten, and everyone would live happily. One of Marxism’s major failings is placing so much emphasis on economic matters while downplaying—almost dismissing—factors such as religion and ethnic pride. For example, in today’s Middle East, if all economic problems were suddenly solved, it’s difficult to imagine that all other problems would go away, too

Many of the details of Marxism didn’t blend with one another. Marx’s moral disagreement with capitalism and particularly his studies which showed communism was unavoidable don’t seem to hold up when measured against modern history—Japan, Germany, and the United States have had thriving capitalist economies for decades; and yet, at the dawn of the twenty–first century, a Marxist revolution in any of the three seems almost inconceivable. Marx’s contention that capitalism had to first mature to its fullest state before the inevitable communist revolution was

also disproven in the reverse—Russia hardly had a thriving capitalist economy when the Bolsheviks took over in 1917.

Moreover, Marx’s views on the causes of imperialism were also at odds with events that occurred long after his death. Today’s Isms states: “Communist imperialism cannot be explained in Marxian economic terms, according to which imperialism is the last phase of an advanced capitalist economy with an abundance of capital that it seeks to invest in less developed areas.” Indeed, modern–day Germany and Japan are two examples of capitalist governments that don’t seem to have any imperical ambitions, while the cash–strapped Soviet Union of the mid–twentieth century aggressively set up communist satellite states all over Eastern Europe. Of course, by the mid–twentieth century Stalin had so twisted communist theory that Marx himself likely would’ve been disappointed if he had seen what the first country to base itself on his ideas had become. The truly ironic thing is if Marx had been around in the 1930s to express those disappointments in Stalin’s Russia, he probably would’ve found himself exiled to Siberia—or worse.

Marx also believed that, after the communist revolution, the class structure of society would disappear. But that was not the case in Soviet Russia. Indeed, the proletariat fell even further behind the small class of quasi–intellectual government officials who—in the name of the state—controlled the means of production. In fact, it has been the advanced capitalist economies that showed a change for the better. Of the twentieth–century capitalist societies, Eugene O. Porter writes in Fallacies of Karl Marx: “The mid- dle–class is not disappearing, but increasing, as a result of the greatly expanding educational system which produces professional men and women—doctors, lawyers, teachers, etc., most of whom are property owners and therefore of the petty bourgeoisie as defined by Marx.”

Marx and Engels claimed that, scientifically, socialism was the only way history could end. They called this theory “scientific” socialism and considered it much more sound than the idealistic dreams of the utopians. Engels, after Marx’s death, hinted that their theories may need modification, given that socialism had yet to ensue.

After Vladimir Lenin came to control Russia in 1917, his version of Marxism became known as Marx- ism–Leninism. He altered many of Marx’s ideas to rationalize his seizure of power and the atrocities committed by his Bolshevik party. He justified the ends by the means and was willing to do anything to force socialism onto tsarist Russia.

P o l i t i c a l |

T h e o r i e s |

f o r |

S t u d e n t s |

2 2 5 |

M a r x i s m

Friedrich Engels.

Lenin added to Marxism the idea that a new party had to be created to control the working class. He also added the idea of Marxist revolution in one country instead of the worldwide revolution that Marx had predicted. Lenin sought control rather than leadership. His dictatorship became more severe when he encountered opposition that could force him from power. He felt compelled to silence it, and did.

The Bolsheviks changed their name to the Communist Party in 1918 to distinguish their revolutionary selves from the moderate Marxists in Western Europe. The Communist International, set up by the Bolsheviks in 1919, was separate from the Second International’s organization of socialist parties. Lenin wanted only revolutionary socialism and so created the Communist International to allow for a split.

Marxism–Leninism, signified socialist ideology in tandem with mass murder. Lenin voiced some comments on Marxism that shed light on some of the causes of its struggle in Russia. In his 1923 speech, “Better Fewer, But Better,” Lenin spoke about some of the areas in which his Marxism had strayed from the vision recorded by Karl Marx.

Lenin’s speech, by title and content, included the idea that rule was better controlled by a small, competent minority than by the masses. This was a direct split from Marx’s contention that the revolutionary

party would succeed because of its control by the masses, or the proletariat (the working class.) Lenin’s statement, “We must follow the rule: Better fewer, but better,” was a switch from the Marxist ideals he planned to follow.

Lenin also felt that it was important to progress slowly and that change that was forced quickly would eventually ring false. His simultaneous need to be able to defend his country from aggressors was an obstacle, however. The two desires could not find a way to coexist. Lenin stated: “We must show sound scepticism (sic) for too rapid progress . . . we must remember that we should not stint time on building it, and that it will take many many years.” At the same time, Lenin felt: “What interests us is . . . the tactics which we, the Russian Communist Party . . . should pursue to prevent the West–European counter–revolutionary states from crushing us.”

Lenin’s own claims are that to reach a Marxist world, progress could not be rushed, yet at the same time it was imperative to have a powerful country to protect Marxist ideals. Though Lenin said that “. . .

we shall be able to keep going not on the level of a small peasant country, not on the level of universal limitation, but on a level steadily advancing to large–scale machine industry,” he wanted these conflicting goals to happen simultaneously. These plans could have led to their own failure.

Marxism was designed to be a road to equality and freedom. Society would be fair and repressive methods would be unnecessary. The Marxist reality in Russia was very different from the ideology it claimed to follow. The state did not whither into nothing but rather grew until it virtually destroyed everything else. The state controlled everything—industry, agriculture, education, art, and the media. Travel was only allowed with permission and the state spied on its citizens so that it could bury dissension.

There is some debate as to why the quest for Marxism created such blood bath in Russia. Marx believed that checks and balances, as found in the Constitution of the United States, were unnecessary. He felt that the evils of the world would disappear when equality took over because it was the poverty and need caused by capitalism that created the evils to begin with. The Russian experiment of Marxism was a failure. The freedom and equality that Marxism was created to promote were ignored. Crime flourished at the highest level: It did not melt away as Marx had predicted. Marxist theorist Rosa Luxemburg (1871– 1919), commented on the problems of freedom when she said, “Freedom only for the supporters of the government, only for the members of one party—how-

2 2 6 |

P o l i t i c a l |

T h e o r i e s |

f o r |

S t u d e n t s |

M a r x i s m

ever numerous they may be—is no freedom at all. Freedom is always and exclusively freedom for the one who thinks differently.” In Soviet Russia, the ones who thought differently were quite often killed, which may help to explain why freedom was so thoroughly lacking and why, despite good intentions at the onset, Soviet Russia endured such violence in the name of so–called equality.

TOPICS FOR FURTHER STUDY

•Does the evolution of Marxism end with Marx’s death? With Engels’ death? Can Marxists in the twentieth century alter the meaning of Marxism and still call it Marxism, or is Marxism necessarily the philosophy set down by Karl Marx?

•Is Marxism fatally flawed in its assumption that crime will not exist with equality, or is it simply that the world has never really seen equality and thus crime has never had a chance to snuff itself out?

•Although Marxism failed in Soviet Russia, could it succeed elsewhere?

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Sources

Ebenstein, Alan, William Ebenstein, and Edwin Fogelman. Today’s Isms, Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Feinberg, Barbara Silberdick. Marx and Marxism, New York: Franklin Watts, 1985.

Klages, Mary. “Marxism and Ideology,” University of Colorado, Boulder, 1997.

Kort, Michael G. Marxism In Power—The Rise and Fall of a Doctrine, Connecticut: The Millbrook Press, 1993.

Laidler, Harry W. History of Socialism, New York: Thomas Y. Crowell Company, 1968.

Martin, Joseph. A Guide to Marxism, New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1980.

Marx, Karl and Engels, Friedrich. The Communist Manifesto, New York: Verso, 1998.

Porter, Eugene O. Fallacies of Karl Marx, Texas Western College at El Paso, 1962.

Service, Robert A History of Twentieth–Century Russia, Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1998.

Volkov, G.N., ed. The Basics of Marxist–Leninist Theory,

Moscow: Progress Publishers, 1982.

Further Readings

Dunayevskaya. Marxism and Freedom: From 1776 Until Today, Humanity Books, 2000. Traces the history of Marxist Socialism and explains why its opposition to freedom led to its demise.

Marx, Karl and Friedrich Engels. The Manifesto of the Communist Party, 1848. This call to arms to the workers was written by Marx and Engels in the middle of a revolutionary upheaval throughout Europe.

Pelinka, Anton. Social Democratic Parties in Europe, New York: Praeger Publishers, Inc., 1983. Provides more information on the political background which influenced Karl Marx.

Volkov, G.N., ed. The Basics of Marxist–Leninist Theory,

Moscow: Progress Publishers, 1982. Describes Marxist-Lenin- ist theory and its relationship to capitalism.

SEE ALSO

Capitalism, Communism, Socialism, Utopianism

P o l i t i c a l |

T h e o r i e s |

f o r |

S t u d e n t s |

2 2 7 |

OVERVIEW

Nationalism is sometimes labeled a political phenomenon or ideology that is not truly a theory. Some political activists and scholars see nationalism not as something to be theorized about but merely as a strong, sentimental feeling about one’s own country, a patriotic fervor directed toward advancing the “national interest.” Others view nationalism as the driving philosophy behind social movements that can both infect and inspire (depending on one’s viewpoint) large numbers of people living in the same geographical region to attack other groups or countries for the anticipated benefit of one’s interests. Still others see nationalism as a phenomenon that can be appropriately conceptualized and described, analyzed, and explained in theoretical terms. The variety of perspectives on nation- alism—whether, for example, nationalism simply exemplifies overzealous feelings for one’s country or is rightfully placed within the scope of political theo- ries—has fluctuated over time. At certain periods in history, no one talked about “nationalism” per se, although the concept of “nations” appeared during European Middle Ages, if not earlier. Nationalist movements seem not to have occurred before the eighteenth or early nineteenth century. Beginning with the fall of the French Emperor Napoleon in the early 1800s and the expansion of European imperialism across Africa and Asia in the late nineteenth century, nationalism increasingly appeared as a phenomenon whereby those seeking independence from imperial powers claimed rights to self–determination and gathered support for their national liberation movements.

Nationalism

WHO CONTROLS GOVERNMENT? State officials

HOW IS GOVERNMENT PUT INTO POWER? Crisis situation

WHAT ROLES DO THE PEOPLE HAVE? Support the nation

WHO CONTROLS PRODUCTION OF GOODS? Owners of

capital

WHO CONTROLS DISTRIBUTION OF GOODS? Owners of

capital

MAJOR FIGURES Ernest Renan; Johann Gottfried

Herder

HISTORICAL EXAMPLE Republic of Turkey, 1923–

present

2 2 9

N a t i o n a l i s m

CHRONOLOGY

c.1142: Dekanawidah establishes the

Haudenosaunee (Iroquois) confederacy of five Native American nations.

1320: Growing nationalism among the Scots and warfare with England results in the Scots’ Declaration of Arbroath.

1800: German theologian Johann Gottfried Herder publishes his Outline of a Philosophy of a History of Man.

1806–1807: German philosopher Johann Gottlieb Fichte delivers his lectures, “Addresses to the German Nation.”

1882: Ernest Renan lectures on “Qu’est–ce qu’une nation?” (“What is a nation?”).

1914–1918: World War I devastates Europe.

1939–1945: World War II ravages Europe, North Africa, East Asia, and Southeast Asia.

1944: Hans Kohn publishes The Idea of Nationalism: A Study of Its Origins and Background.

1950s—1960s: National liberation movements in many African colonies of European imperial powers produce a rapid succession of newly independent African states.

1981: Anthony D. Smith publishes The Ethnic Revival in the Modern World.

1983: Ernest Gellner publishes Nations and Nationalism.

tion of national identities and of nationalism as something far more complex than can be adequately summarized into two categories. Similarly, differences of opinion are to be found as to whether nationalism is a modern phenomenon, appearing only when societies shifted from feudalism to capitalism and began to form independent states, or whether nationalism has existed for centuries, if not millennia, as the natural expression of people’s deepest sense of their cultural and ancestral roots. By the late twentieth century, many assumptions typical of the earlier theoretical approaches to nationalism were challenged by the rise of movements throughout the world advocating ethnic separatism and irredentism (“consolidationist” movements, in the words of Deborah Larson of the University of California at Los Angeles, as cited by Kristen Williams in Despite Nationalist Conflicts). The growing demands of indigenous peoples for political and cultural self–determination and the increasing heterogeneity of populations in multicultural societies in much of the developed world also are challenging traditional notions of nationalist theory at the start of the new millennium.

HISTORY

Nationalism, as a field of study, is fraught with controversial interpretations, including disagreement over when nationalist thinking and nationalist movements first appeared. The historical review presented here of the development of nationalism in theory and in practice thus should be read with an awareness of this lack of consensus among scholars as to the exact nature of nationalism, the causes for its arising in particular societies and periods of history, and the best way it should be theorized.

In the late twentieth century, particularly after the demise of the Soviet Union in 1991, the study of nationalism became a well–developed field, crossing the disciplinary boundaries of political science, sociology, anthropology, international relations, and history. Theories of nationalism can be divided into roughly two major categories: ethnic nationalism, based on concepts of shared ethnic identity, and civic nationalism, based on shared appreciation and respect for key political values.

Other theorists, including scholars from the developing world, have viewed the theoretical construc-

Beginnings

That said, it is worth noting that early examples of the concept of the nation can be found in both the European and the non–European world, together with rather precise political formulations of how nations should function and work together. For example, at some point between the eleventh century and the early sixteenth century (estimates of the exact date range from 1142 to 1450), Dekanawidah, known as The Peacemaker, emerged from the Native American nation of the Hurons in the Great Lakes region to establish the Haudenosaunee (pronounced “ho–dee– no–sho–nee,” known by the French as the Iroquois), a political confederation of five (later, six) Native American nations living in the northeastern region of what would later be the United States of America.

2 3 0 |

P o l i t i c a l |

T h e o r i e s |

f o r |

S t u d e n t s |

N a t i o n a l i s m

Across the Atlantic, at about the same time, the system of feudal states and monarchical rule established during the European Middle Ages gradually was reshaped as commerce grew, urban areas developed, and the Renaissance introduced new concepts of the position of man (and woman) within European society. Among the earliest European groups to build a national identity were the Scots, who between 1296 and 1328 fought King Edward I (1239–1307) and the English in the Scottish Wars of Independence. Prepared on April 6, 1320, the Declaration of Arbroath, the Scottish nation’s formal declaration of independence from England, was drawn up at the Monastery of Arbroath in Scotland and sealed by 38 Scottish lords. Addressed to the Pope, the Declaration spoke of the Scottish nation and urged the Pope to disregard the English claim on Scotland, which the Pope subsequently did.

On October 24, 1648, the Treaty of Westphalia was signed between the King of France, the Holy Roman Emperor, and their allies, ending the Thirty Years’ War between Catholics and Protestants in Europe and marking new boundaries for European states. For the most part, however, a genuine sense of national identity had yet to develop among the peoples living in each of these European states. Although religious influence on political affairs would continue to shape history, governments would now be based more on a secular rather than religious rule. In 1690, a half–century after the Treaty of Westphalia, English physician John Locke (1632–1704) published his “Second Treatise on Government,” further developing English philosopher Thomas Hobbes’ (1588–1679) “social contract theory” to identify civil government as resting on the consent of the governed. Locke’s writings are now seen by many as having sparked the “Age of Enlightenment” in Europe—a period in history when the rights of individuals were enumerated and exalted and the concept of government based on the will of the people took hold. Interest in democratic self–governance and political self–determination grew among European and American philosophers and ordinary citizens alike.

Transformations

France, one of the most powerful European countries at the time, underwent profound political changes in 1789. On July 14 an angry mob stormed the Bastille Prison in Paris, sparking the French Revolution with the goal of achieving “Liberty, Equality, and Fraternity” for all citizens living in France. The growth of a “bourgeois” middle class had led to demands by commoners for a greater say in their governance, which up to then had been controlled mainly by the

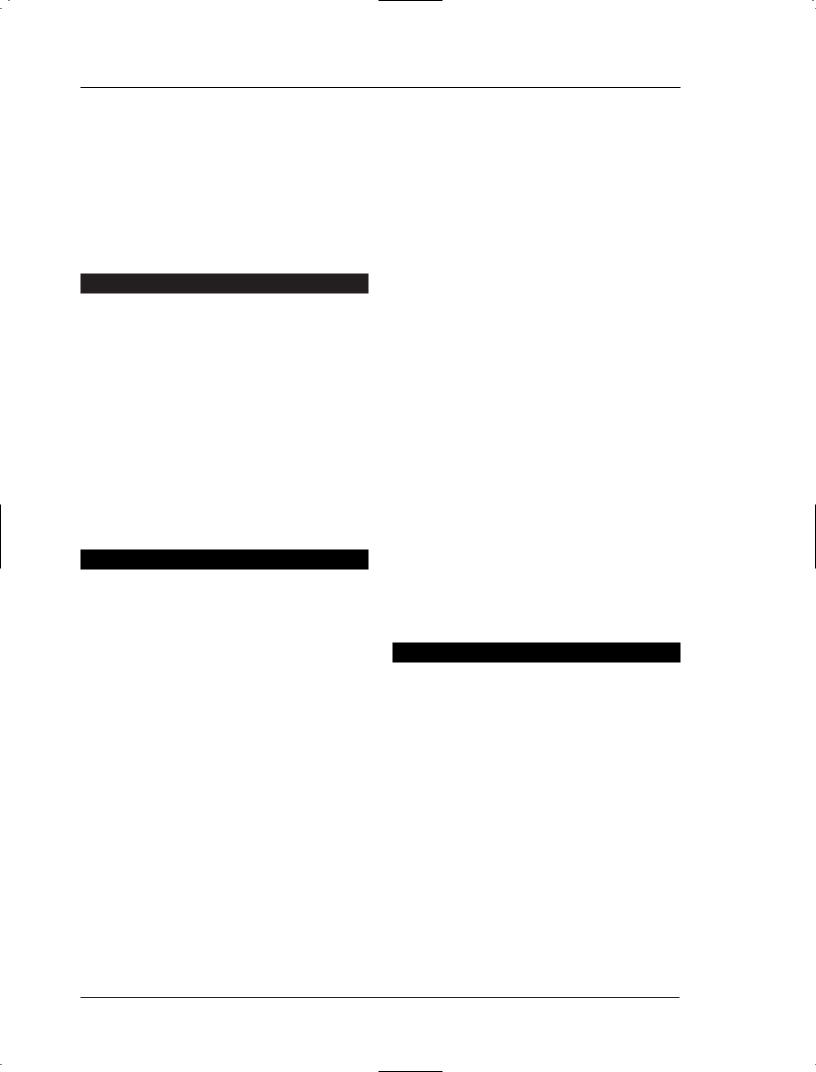

Johann Gottfried Herder.

clergy and the nobility. October 16, 1793 saw the execution by guillotine of Queen Marie Antoinette and King Louis XIV of France, ending royal rule in France and paving the way for an attempt at democratic rule. However, the repression and violence visited upon those unwilling to subscribe to the new method of government was so enormous that the country fell back into disarray under the “Reign of Terror” of the Jacobins, who wished to instill an excessive degree of control and order on French society and to eliminate all who they deemed enemies. A decade later, Napoleon Bonaparte, a general in the French army, led the French people on an expansive campaign to conquer Europe.

Witnessing the transformation of European states away from monarchical rule, German theologian Johann Gottfried Herder (1744–1803) published his Outline of a Philosophy of a History of Man, a set of theories developed by Herder between 1774 and 1781, which detailed his views on the proper identity of nations and on the growth of nationalism. In this document and others he wrote over the next two decades, Herder promoted the idea that true nations are comprised of persons who share a common ancestry and linguistic heritage, along with common cultural and religious traits. His idea of “romantic nationalism” was one of the earliest theoretical portraits of nationalism as stemming from the desires of language

P o l i t i c a l |

T h e o r i e s |

f o r |

S t u d e n t s |

2 3 1 |

N a t i o n a l i s m

BIOGRAPHY:

Johann Gottfried Herder

Johann Gottfried Herder was born on August 25, 1744, in Mohrungen, East Prussia, a Central European state with a population largely Germanic in ancestry. Herder began his formal academic studies in the field of medicine but later switched to theology. Listening to lectures of the famous philosopher Emanuel Kant during his studies from 1762–64, Herder became particularly interested in Kant’s geography lectures on the relationships among “meteorological, physical, and human factors.” Through his studies with Kant, Herder also came to know the writings of French philosopher Jean–Jacques Rousseau and the English empirical philosophers. In 1764 Herder moved to Riga in the Russian Empire, where he preached and taught for five years. In 1767 Herder was ordained a minister, served in two churches in Riga, and taught in the Cathedral School there. Increasingly well known and respected as a writer, Herder published his first book, Uber die neuere deutsche Litteratur. Fragmente (Excerpts from Recent German Literature) at age twenty–three.

In 1769 Herder moved to France, keeping a diary of his voyage by sea, which was published after his death and revealed his hopes of becoming a world– famous writer and a significant political actor. Herder apparently wished to reform the Russian education system and to devise a new constitution for Russia.

After arriving in France, Herder increasingly saw himself as German and felt depressed by the decay of French political and social life in the decades preceding the French Revolution. In 1770 Herder was invited to tutor the son of the Prince of Holstein back in Prussia and to travel with his young student to Italy.

Disenchanted by life in the French capital and attracted by this new offer, Herder quickly left Paris and moved to Eutin, Holstein’s capital city, in March 1770 to begin tutoring. On the way to Italy with the prince’s son, Herder stopped in Hamburg and Darmstadt, where he met the woman he later would marry, Caroline Flachsland. However, apparently feeling humiliated by how he was treated as a tutor, Herder quit his job after reaching Strasbourg with the prince’s son in July 1770. There, Herder sought treatment at the Strasbourg Faculty of Medicine for an eye problem that had afflicted him since childhood. While in Strasbourg, Herder started up a lifelong friendship with the German poet Goethe, leading to his eventual move to Weimar, where Goethe was minister of the court of Duke Karl August. In 1776, Goethe convinced the Duke to make Herder Superintendent of Schools, Chief Pastor, and Court Preacher. Herder came to Weimar, where he spent a quarter of a century, dying there on December 18, 1803.

communities to shape their own destinies and to create their own territorial states.

Johann Gottfried Herder

Johann Gottfried Herder was one of the earliest of the European writers on nationalism. His principal works include A Treatise upon the Origin of Language (1772) and Outline of a Philosophy of the History of Man (1784–91). Herder’s concept of nationalism focused on the cultural side of nation formation, with ethnicity figuring much more significantly in the development of nationhood than the more “civic” aspects featured by later theorists. In Herder’s Social and Political Thought: From Enlightenment to Nationalism, F.M. Barnard described Herder’s life and the development of his nationalist vision, noting that Herder’s conception of nationalism emerged during the German Romantic period that began in the eighteenth century. At that time, the idea of a German national identity

grew in popularity across the feudal states that eventually would be united as the German Confederation of 1815 and later, in 1871, as the German Empire.

Despite his personal charisma and ability to attract others to take part in stimulating intellectual discussions and correspondence with him, Herder became increasingly isolated in his work and views and dissatisfied with life as he aged. Nonetheless, he reportedly was a keen observer of his surroundings and enjoyed being of service to others. Herder’s discontent with the social and political life of his times had much to do with the lack of democratic practices in eighteenth century German society. Concerned with social justice, Herder objected to the exclusionary nature of German hereditary politics, nobility, and feudal structures, to the arbitrariness of political tyrants, and to the continual warfare of nations that sought to dominate each other. He was especially opposed to slavery and colonialism.

2 3 2 |

P o l i t i c a l |

T h e o r i e s |

f o r |

S t u d e n t s |