Учебники / Pediatric Sinusitis and Sinus Surgery Younis 2006

.pdfDiagnostic Workup for Pediatric Rhinosinusitis |

45 |

56.Garbutt JM, Gellman EF, Littenberg B. The development and validation of an instrument to assess acute sinus disease in children. Qual Life Res 1999; 8(3):225–233.

57.Kay DJ, Rosenfeld RM. Quality of life for children with persistent sinonasal symptoms. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2003; 128(1):17–26.

58.Garbutt JM, Goldstein M, Gellman E, Shannon W, Littenberg B. A randomized, placebo-controlled trial of antimicrobial treatment for children with clinically diagnosed acute sinusitis. Pediatrics 2001; 107(4):619–625.

59.Anand VK, Panje WR. Practical Endoscopic Sinus Surgery. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1993.

4

Adult Versus Pediatric Sinusitis

Raphael Chan

Bossier City, Louisiana, U.S.A.

Frank C. Astor

Departments of ENT and Otolaryngology, University of Miami, Miami, Florida, U.S.A.

Ramzi T. Younis

Department of Pediatrics, University of Miami, Miami, Florida, U.S.A.

INTRODUCTION

Rhinosinusitis implies inflammation of the mucosa of the nose and paranasal sinuses including infectious and noninfectious processes. Even though this definition is true for children and adults, there are enough age-related variances relevant to its diagnosis and treatment to require specialized expertise.

Differing predisposing factors in the pathogenesis of sinusitis in children and adults contribute to their differences in presentation, clinical course, and management. It is the intention of this chapter to highlight important clinical aspects that physicians will encounter between both groups. Knowledge of sinusitis, with its multifactorial etiologies, continues to evolve as a disease with manifestly age-related characteristics.

ANATOMY

In childhood, the sinuses undergo progressive and continuous growth and development. At birth, only the maxillary and ethmoid sinuses are present to be clinically significant. The maxillary sinuses show two growth spurts,

47

48 |

Chan et al. |

initially within the first three years, and subsequently from 7 to 18 years. Before age nine, the sinus floor sits higher than the nasal floor; thereafter, the sinus floor is lower than the nasal floor. This is a consideration in the planning of intranasal approaches to the maxillary sinuses in children, and in the diagnosis of odontogenic sinusitis in adults. The ethmoid sinuses are not significant in size at birth but are determinable radiologically by age one, reaching adult size by 12 years of age. The frontal sinuses develop slowly and at one year they are just perceptible. By six they can be radiologically demonstrated and grow rapidly from 12 years to reach adult size in the late teens. The frontal sinuses do not generally give rise to infections until after puberty. The sphenoid sinus is small at birth, but progressively invades into the sphenoid bone and, has reached the sella turcica by age seven. Growth of the sphenoid sinus continues into adulthood to wrap adjacent structures that form indentations in the wall of the fully developed sinus.

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

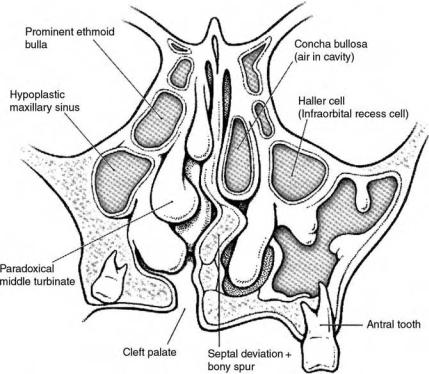

Sinus pathophysiology is largely based on the impaired drainage through the ostia. Normal physiology depends on the integrity and patency of the sinus ostia, the ciliary function, and the quality of the secretions. Pathology involving any of these factors, either singly or in combination, will create an obstruction of the drainage pathways, resulting in the entrapment of secretions (Fig. 1). This pooling of secretions with subsequent inflammatory changes, acidosis and anaerobiosis, forms the environment ideal for microbiological growth.

Upper respiratory infection (URI) and allergy are the most common predisposing factors to sinusitis in children, commencing with edema and mucosal swelling and concurrent narrowing at the ostio meatal regions. By comparison, because the ostia are smaller in children as compared to adults, these factors play a more significant role in children (2).

Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) is an apparently important condition associated sinusitis, especially in children more than two years old

(3). Many uncontrolled studies have supported this link as the vigorous treatment of GERD in these patients has resulted in the reduction of symptoms. However, the authors are cognizant of the need for prospective doubleblind control studies to conclude that GERD contributes to sinus disease.

Adenoids probably play a role in rhinosinusitis in children (Table 1). By virtue of their size, they can obstruct the normal drainage from the sinuses into the nasopharynx, causing backflow and pooling. However, their significance is called into question when functional endoscopic sinus surgery (FESS) and adenoidectomy have been compared in studies showing the superiority of the former (5). In the adult, adenoids are expected to involute and are not as important. Evidence of lymphoid hyperplasia in the adult nasopharynx should raise suspicion of malignancy.

Adult Versus Pediatric Sinusitis |

49 |

Figure 1 Anatomical factors contributing to sinus disease. Source: From Ref. 1.

Nasal polyps are another major contributing factor in chronic sinusitis by obstructing the ostia. However, they are rare in children and their presence in this age group calls for further investigation for cystic fibrosis, allergic fungal sinusitis, or allergy. The adolescent male that presents with a hemorrhagic polyp should be evaluated for juvenile nasopharyngeal angiofibroma. Patients with cystic fibrosis may initially present with sinusitis since more than 10% develop nasal polyps by three years of age. Children with intractable or chronic sinusitis should also be investigated for immune deficiency states and for ciliary motility dysfunction (6). Presence of nasal polyps in the adult may raise suspicion of neoplasia under special circumstances and require biopsy, particularly if unilateral or with associated invasion or erosion.

MICROBIOLOGY

Community-acquired acute sinusitis studies consistently show the presence of S. pneumoniae, Moraxella catarrhalis, and H. influenzae as the most important pathogens in adults and children. Staphylococcus aureus and

50 |

Chan et al. |

Table 1 Extrinsic and Intrinsic Causes of Chronic Rhinosinusitis

Extrinsic causes of CRS can broadly be broken down into:

Infectious (viral, bacterial, fungal, and parasitic)

Non-infectious/inflammation

Allergic-IgE-mediated

Non-IgE mediated hypersensitivities

Pharmacologic

Irritants

Disruption of normal ventilation or mucociliary drainage

Surgery

Infection

Trauma

Intrinsic causes contributing to CRS:

Genetic

Mucociliary abnormality Cystic fibrosis

Primary ciliary dysmotility Structural Immunodeficiency

Acquired

Aspirin hypersensitivity associated with asthma and nasal polyps Autonomic dysregulation

Hormonal

Rhinitis of pregnancy Hypothyroidism

Structural

Neoplasms

Osteoneogenesis and outflow obstruction Retention cysts and antral choanal polyps

Autoimmune or idiopathic

Granulomatous disorders Sarcoid

Wegener’s granulomatosis Vasculitis

Systemic lupus erythematosus Churg-Straus syndrome

Pemphigoid

Immunodeficiency

Abbreviations: CRS, chronic rhinosinusitis. Source: From Ref. 4.

anaerobic flora are more common in chronic adult sinusitis than in children

(7). Pseudomonas aeruginosa play an important role in cystic fibrosis and in the immunocompromised adult or in nosocomial or intensive care unit (ICU) acquired sinusitis. Nevertheless, although it is worth mentioning

Adult Versus Pediatric Sinusitis |

51 |

the role of opportunistic fungal infections in HIV and diabetic patients, it is beyond the scope of this chapter to further the discussion, except to state that they are seen in all age groups.

THE CLINICAL DIAGNOSIS OF SINUSITIS

The categorization of sinusitis in children and adults is similar and arbitrarily based on the duration of symptoms rather than on severity. Clinical diagnosis of acute sinusitis has been defined by major and minor criteria for symptoms that exist for longer than seven days (Table 2). The presence of any two major criteria or one major and two or more minor criteria are highly suggestive of acute or sub-acute sinus disease (8). Acute sinusitis is

Table 2 Clinical Diagnosis of Rhinosinusitis

Signs and symptoms

Major criteria

Purulent nasal discharge

Purulent pharyngeal drainage

Cough

Minor criteria

Periorbital edemaa

Headacheb

Facial painb

Tooth painb

Earache

Sore throat

Foul breath

Increased wheeze

Fever

Diagnostic tests

Major criteria

Waters’ radiograph with opacification, air fluid level, or thickened mucosa50% of antrum

Coronal CT scan with thickening of mucosa or opacification of sinus Minor criteria

Nasal cytologic study (smear) with neutrophils and bacteremia Ultrasound studies

Probable sinusitis

Signs and symptoms: 2 major criteria or 1 major and minor criteria Diagnostic tests: 1 major ¼ confirmatory, 1 minor ¼ supportive

aMore common in children. bMore common in adults. Source: From Ref. 8.

52 |

Chan et al. |

characterized by symptoms persisting more than seven days, by resolution of disease between bouts, and occurring less than four times per year. Sub-acute sinusitis has been defined as disease with symptoms and signs lasting four weeks to three months. It is generally agreed that chronic sinusitis refers to disease lasting more than three months, associated with irreversible disease such as osteal obstruction or polyposis.

Children

The most common presentations of sinus disease in children are cough and rhinorrhea. The cough is typically worse at night, the rhinorrhea purulent and associated with nasal obstruction. Other complaints may include fever, halitosis, irritability, pallor, wheezing, or periorbital edema. The child harboring a ‘‘cold’’ that seems more severe than normal with high fever, purulence, and discharge could signify a sinus infection complicating a viral URI. In children with allergy, sinusitis should be considered when not responding to historically effective treatment or if resolution is rapidly followed by recurrence (9).

Older children, who are able to vocalize, may complain of headache, sore throat, or earache. Since these are uncommon complaints under the age of eight, their presence denotes the ominous possibility of sinus complications (10). In contrast with adults, the initial presentation of sinusitis in children is the complication of the sinusitis. Up to 60% of children with chronic sinusitis present with associated middle ear disease (11). Other presentations in chronic disease include laryngitis, bronchitis, and periorbital cellulitis.

Adults

Adult symptoms are more frequently localized to the specific sinus involved. Sinus pain and tenderness are significant complaints. There is accompanying nasal congestion and mucopurulence. Severe infections correlate with more prominent symptoms and signs such as headaches, pyrexia, and even delirium.

In acute sinusitis, the pain is often sharp and stabbing. Even though often localized, sinus pain will radiate to other regions of the head and neck. Bending, straining, and coughing aggravate its intensity. Maxillary pain initiates from the inner canthus of the eye or cheeks and may radiate to the molars or the ears. Ethmoid sinus pain is localized over the bridge of the nose and behind the eye. Eye movements intensify it. Frontal sinus pain clinically occurs over the forehead and may radiate to the temples or the occiput. Isolated sphenoid sinusitis is rare and often late in being recognized, presenting as ill-defined headache often associated with neurological deficits of adjacent cranial nerves.

Adult Versus Pediatric Sinusitis |

53 |

DIAGNOSTIC AIDS

Transillumination

The increased thickness of the soft tissue and bony vault in children under 10 years of age limits the clinical usefulness of transillumination in children. The use of transillumination in adults will give information as to the state of the maxillary and frontal sinuses, but will not be effective in evaluating the ethmoid and sphenoid sinuses. In adults, transillumination had a sensitivity of 73% and a specificity of 54% when compared with a positive sinus radiograph (12).

Ultrasonography

The use of A-mode ultrasound is popular in Europe with numerous studies showing high correlation between mucosal thickening on plain sinus films, ultrasound, and antral puncture. Ultrasonography (US) was met with initial enthusiasm in the United States but later studies did not support its usefulness. US may have a role in the diagnosis of acute sinusitis during pregnancy given all its inherent limitations, obviating the need for radiation exposure (13).

Radiology

Radiological studies may not be helpful in children under six years of age. Furthermore, CT scans may over diagnose rhinosinusitis by documenting an overwhelming presence of abnormal CT scan findings in children and infants who had a preceding URI of two weeks (14). For adults, the incidental changes on CT are not dissimilar (15). Although rarely ordered by the specialist, plain films may be indicated in the primary setting in adults (16). Indications for magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) in children and adults remain similar and MRIs are used mostly to exclude intracranial disease or to distinguish inflammatory and neoplastic margins.

Endoscopy

In the adult, office endoscopy allows for the complete examination of the nasal cavity and the nasopharynx, enabling the detection of anatomical abnormalities or findings that may contribute to the development of rhinosinusitis. Indeed, 9% of patients with normal sinus CT scans had abnormal endoscopic findings in one study (17). A most accurate diagnosis of sinusitis, endoscopy relies on the visualization of mucous draining from the middle meatus (18). Purulent crusting may be seen with the effects of drying and dehydration. Swelling over the affected sinuses, polypoid degeneration, or frank polyposis may also be observed. However, endoscopy is not an easy task in children, who may resist any attempts at inspection. Endoscopy requires full cooperation from the patient and hence it is not generally suitable in the ambulatory setting in very young children.

54 |

Chan et al. |

COMPLICATIONS

Odontogenic Sinusitis

The normal adult size of the maxillary sinus is not reached until approximately 20 years of age. In the fully developed maxillary sinus, the two upper premolars and the upper molars may be separated from the antral cavity by just the periosteum. Sinusitis of dental origin is hence more common after the second decade (19).

Acute odontogenic sinusitis is always unilateral with exquisite tenderness on palpation or percussion of the diseased molar or premolar tooth. Odontogenic sinusitis accounts for 5 to 10% of acute sinusitis. Anaerobes are found in 50% of all these patients and accounts for the feculent odor that accompanies these infections. The presence of zinc in aspergillosis maxillary sinusitis is related to the overfilling of dental paste. Zinc has been found to stimulate the growth of Aspergillus fumigatus. In one series, a radiopaque foreign body was seen in 94% of the cases (20). Root canal therapy can provoke periapical inflammation adjacent to the floor of the maxillary sinus. Instrumentation can introduce bacteria into the sinus and cases of sinusitis have followed endosseeous implant into the posterior maxilla.

Orbital Complications

The ethmoid sinuses are present since birth, and infections of the ethmoid sinuses can arise at any age. Approximately 80% of all orbital complications from ethmoid sinusitis are in children (21). The paper-thin bony plates that separate the ethmoid and maxillary sinuses from the orbit are easy conduits for infections to spread in this age group (22). Chandlers’ classification describes the progressive orbital infection from sinusitis.

Intracranial Complications

The intracranial spread of frontal, ethmoid, and sphenoid sinuses can lead to the development of meningitis, brain abscess, and peridural abscesses. Brain abscess is one of the most common intracranial complications of sinusitis exceeded only by orbital complications. In younger children, the ethmoid and maxillary sinuses are present at birth and are the most common sources of intracranial complications in this age group. The frontal and sphenoid sinuses are rarely implicated due to their later development in life. Whereas intraorbital complications are more frequent in younger children, intracranial sequelae are most common in older children and adults (Table 3). Brain abscesses are most likely to occur in the frontal lobe, either due to direct extension of the infection or through venous transmission.

The maxillary sinuses are rarely involved in direct intracranial spread because of the distance from the cranium (23). Isolated sphenoid sinusitis has been associated with ipsilateral involvement of the ophthalmic or