2

Civic Talk and Civic Participation

It seems at least plausible that those explicitly named by respondents as people with whom they discuss politics may be a biased selection of those with whom politics is actually discussed.

—Michael Laver (2005, 934)

n this chapter I lay down the foundation of my argument by examining Ithe existing scholarship on civic talk and civic participation. I then show how our understanding of the relationship between these two phenomena can be made clearer with new evidence. In the chapters that follow, I use a number of different sources of data to show how and why civic talk

affects how we participate in civil society.

What Is Civic Talk?

Civic talk is the informal discussion of politics and current events that occurs within a social network of peers: the friends, colleagues, family members, and other individuals who are present in our social environment. A variety of examples of this type of behavior exist, including talking about the news of the day over a family dinner, discussing the economy during a coffee break at work, chatting among patrons at a bar about the current election, and other such informal discussions. Typically, these types of interactions are not purposively sought. Instead, civic talk is usually an unintended byproduct of people going about their normal daily routine (Downs 1957; Klofstad et al. 2009; Walsh 2004). For example, a husband and wife might sit down to dinner together and end up discussing

12 |

Chapter 2 |

the issues that were covered in the news that day, or a group of friends socializing at a party might end up talking about the current election, or co-workers might end up discussing the state of the local school system during a lunch break.

Because civic talk is “accidental,” it is important to underscore that it is distinct from another form of political discussion that is examined in the political science literature: deliberation. In contrast to the informal nature of civic talk, deliberation is a more formal process where citizens are brought together for the expressed purpose of formulating government policy (Barabas 2004; Conover et al. 2002; Delli Carpini et al. 2004; Mendelberg 2002; Page and Shapiro 1992). Civic talk is not as purposive or formal as deliberation.

If civic talk is a natural part of daily life, how often do we engage in it? Politics and current events may not be at the top of everyone’s list of favorite discussion topics, but most of us do engage in civic talk at least from time to time. For example, respondents to the 2008–2009 American National Election Studies Panel Study were asked, “During a typical week, how many days do you talk about politics with family or friends?” About 91 percent of respondents said they engaged in such discussions at least once a week. On average, respondents reported that they engaged in civic talk about three days per week.1

If most people do engage in civic talk, at least sometimes, then who do they talk to? Because civic talk is a byproduct of going about our normal everyday lives, people do not typically seek out specific individuals with whom to talk about politics and current events. Instead, we tend to talk about these matters with the same set of people with whom we discuss other topics (Huckfeldt and Sprague 1995; Klofstad et al. 2009; McClurg 2006; Mutz 2002; Walsh 2004). Table 2.1 offers an illustration of the overlap between political and non-political discussion networks. These data come from the 1996 Indianapolis–St. Louis Study conducted by Huckfeldt and Sprague (2000). That study is uniquely tailored to answering the question of who we discuss politics and current events with because it used two different methods to collect information on civic talk. Half of the respondents in this study were randomly selected to provide information on the individuals with whom they discussed “important matters” in their life. The other half of the respondents were asked to

1These figures are taken from wave 9 of the study, collected in September 2009. Responses to this question collected in waves 10 (October 2009) and 11 (November 2009) yield comparable results.

Civic Talk and Civic Participation |

13 |

TABLE 2.1 Composition of political and core discussion networks

|

|

|

Subset of |

|

|

|

“important matters” |

|

Political |

“Important matters” |

network that |

|

discussion network |

discussion network |

discusses politics |

|

|

|

|

Spouses (%) |

13 |

16 |

17 |

Other family members (%) |

25 |

30 |

30 |

Coworkers (%) |

23 |

15 |

15 |

“Close” friends (%) |

66 |

73 |

74 |

Sources: 1996 Indianapolis–St. Louis Study (Huckfeldt and Sprague 2000). This table is a partial reproduction of Table 2 in Klofstad et al. (2009).

provide information on the individuals with whom they specifically “discuss politics.”2

The data presented in Table 2.1 show that political discussion networks consist of more or less the same people with whom we discuss other matters. The data in the first two columns of the table suggest that “important matters” discussion networks are, perhaps, a bit more socially intimate. Political discussants are less likely to be spouses (t = −2.45, p =

.01) or family members (t = −3.20, p < .01), and more likely to be coworkers (t = 6.63, p < .01) when compared with “important matters” discussants. And while members of the political discussion network are as likely as “important matters” discussion partners to be considered “friends,” they are less likely to be considered “close friends” (t = −4.36, p < .01). However, while statistically significant, most of these differences are not substantively large. Moreover, comparison of the second and third columns of Table 2.1 shows that the individuals we choose to discuss politics with in our core “important matters” social networks look like the rest of the individuals in that network. Otherwise stated, in going about our daily lives we tend to engage in civic talk with the same people with whom we discuss other topics.

What Is Civic Participation?

The dependent variable of interest in this book is civic participation. “Civic participation” is a term that is used frequently in academic writings and the popular press these days. This is especially the case because many

2For a detailed discussion of these two methods of soliciting data on civic talk, see Klofstad et al. 2009.

14 |

Chapter 2 |

The State

Civil Society

Private Life

Political Participation

(e.g., voting, contacting elected officials, etc. …)

Non-Political Participation

(e.g., participating in voluntary civic organizations)

FIGURE 2.1 What is civic participation?

observers feel that we are in an era of civic disengagement in the United States (see, e.g., Putnam 2000). However, while “civic participation” has become a common term in everyday language, it is important to clarify what this phenomenon is and why it is important for our understanding of how democracy works.

Simply stated, civic participation is activity that draws individuals out of their private lives and into civil society. The diagram in Figure 2.1 presents this definition graphically. The left-hand side of the figure represents a simple society, showing government at the top, and each individual’s private life—or the “private sphere”—at the bottom. In between the state and private life we find civil society, or the “public sphere.” Civil society is the space where citizens are able to step out of their private lives and associate with one another. This space is both literal, as in the local town square where citizens congregate, and figurative, as in the rights to assemble and speak freely while you are in the town square.

The upward-facing arrow in Figure 2.1 illustrates the ways in which civil society upholds popular sovereignty. The arrow symbolizes the ability of citizens to articulate their views to the government by voting, engaging in protests, contacting their legislators, and other such activities. The upward-pointing arrow also symbolizes the fact that participation in public life gives citizens the means to push back against the government to prevent tyranny. In other words, civil society serves as both a bridge and a barrier between the state and the private sphere (Foley and Edwards 1996; Gellner 1995; Hall 1995).3

3It is worth noting that civil society is a necessary, although not sufficient, condition for democracy. For example, civil society was extremely vibrant in the German Weimar Republic. However, because the state was unresponsive to the people during this time period, the

Civic Talk and Civic Participation |

15 |

In addition to protecting popular sovereignty, civic participation is important because it facilitates democratic governance, symbolized by the downward-pointing arrow in Figure 2.1 (Mayhew 1974; Putnam 1993, 2000). For example, Putnam (1993) shows that, despite having similar institutional structures, regional governments in the north of Italy provide better services to their citizens than do those in the south. Even after accounting for a host of alternative explanations, Putnam finds that this variation in governmental performance can be explained by the fact that northern Italians are more active in civil society than are their neighbors to the south (what he calls the strength of the “civic community” or “social capital”). In a more recent study, Putnam (2000) also makes the same claim about the United States. Civil society facilitates democratic governance because civically active citizens demand, and thus tend to get, better policies from the state. Moreover, organizations within civil society can aid in the development and implementation of policy solutions—for example, a soup kitchen can help the state fight hunger and homelessness, an after-school program can help the government combat juvenile delinquency, and the like.

Many different types of behavior fit under this broad definition of civic participation as participation in civil society. The right-hand side of Figure 2.1 splits this large set of activities into two categories: political and nonpolitical civic participation. Under this rubric, civic activities are distinguished based on whether the activity in question directly influences the democratic governing process (Putnam 2000; Tocqueville 2000; Verba et al. 1995; Zukin et al. 2006).

Political civic participation is activity that is aimed at directly influencing the government (see, e.g., Brady 1999; Putnam 2000; Verba et al. 1995). Examples of political civic activities include voting, participating in parties and interest groups, contacting elected officials about important issues, marching or protesting, and working on political campaigns. On the other side of the civic participation coin, we find non-political civic activities. These are activities that pull individuals out of their private lives and into the public sphere but that have no intentional influence on the processes of democratic governance. In practice, non-political civic activity is conceived of and measured as participation in voluntary membership organizations (Putnam 2000; Skocpol 2003; Tocqueville 2000; Verba et al. 1995). Examples include professional associations, philanthropic

door was left open for the Nazis to gain control of the country (Berman 1997). Moreover, the preferences of individuals that choose to participate in civil society are not always representative of those of the wider public (see, e.g., Putnam 2000; Verba et al. 1995).

16 |

Chapter 2 |

organizations, civic leadership groups such as the Elks and the Knights of Columbus, education organizations such as Parent–Teacher Organizations and Parent–Teacher Associations, religious groups, and the like.

In thinking about the distinction between political and non-political civic activities it is important to note that non-political civic activities could have unintended consequences on the governing process. For example, by volunteering in a soup kitchen an individual could have an effect on how the government addresses issues such as homelessness and unemployment. Or by attending a meeting of a religious organization, an individual could be exposed to requests to support a political candidate or party. These examples highlight the fact that the dividing line between political and non-political civic activities is not perfectly definitive. This is especially the case in the United States, where, compared with other industrialized democracies, government is more limited and civil society is more vibrant (Tocqueville 2000; Verba et al. 1995). This said, some method of classifying and distinguishing between the vast numbers of civic acts is needed, and the political–non-political taxonomy serves this purpose. Moreover, as subsequent chapters will show, civic talk can have different effects on how active individuals choose to be in political and non-political civic activities.

A Tautology?

Based on these definitions of “civic talk” and “civic participation,” a question some will have is whether treating civic talk and civic participation as distinct variables is tautological. More specifically, one might argue that informal discussion among peers about politics and current events is itself an act of civic participation. However, while civic talk and civic participation are closely related—this is the central theme of this book—they are distinct concepts.

With reference to Figure 2.1, civic talk is defined and measured as informal discussions that occur in the private sphere. In contrast, civic participation is activity that occurs in the public sphere. The existing body of political science scholarship supports this distinction. For example, through an extensive survey of existing scholarship, Brady (1999, 737; emphasis in the original) concludes that political participation “requires action by ordinary citizens directed towards influencing some political outcomes.” Thus, since “political discussion is not an activity aimed—directly or indirectly—at influencing the government” (Verba et al. 1995, 362), civic talk is not in itself an act of civic participation.

Civic Talk and Civic Participation |

17 |

Social-Level Antecedents of Civic Participation

Now that the independent and dependent variables of interest in this study have been defined, we need to ask what we already know about their relationship to each other. Admittedly, this is not a new research question. Observers as far back as Alexis de Tocqueville, in his seminal study Democracy in America that was conducted in the 1830s, have noted that there is a strong relationship between how individual citizens interact with one another and how well democracy functions.4

In this same spirit, a number of different lines of contemporary social science research have addressed the effect that social-level factors have on various attitudes and behaviors. For example, works in sociology and social psychology show that individuals emulate the attitudinal and behavioral norms of their social network (Festinger et al. 1950; Latané and Wolf 1981; Michener and DeLamater 1999). Economists and sociologists have shown that one’s college roommate can influence a variety of behaviors, such as scholastic achievement (Sacerdote 2001) and binge drinking (Duncan et al. 2005). Research on households shows that people living under the same roof can influence one another to vote (Nickerson 2008). As discussed earlier, the literature on public deliberation shows that individuals become more informed about politics through the process of formulating policy options with other citizens (Barabas 2004; Delli Carpini et al. 2004; Page and Shapiro 1992; Mendelberg 2002). Works on social capital and cooperation illustrate that interacting with fellow citizens causes individuals to have a greater sense of attachment to community, which leads to more frequent participation in civic activities (Dawes et al. 1990; Putnam 2000; Sally 1995). Research on political communication, opinion formation, the mass media, and political socialization shows that the individuals around us influence how we learn about politics because civically engaged individuals provide the rest of us with information about politics (Alwin et al. 1991; Barker 1998; Dawson et al. 1977; Downs 1957; Lazarsfeld et al. 1968; Newcomb 1943; Newcomb et al. 1967; Silbiger 1977; Stimson 1990; Zaller 1992).5

4Or, as Tocqueville (2000, 492) stated it, “Among the laws that rule human societies there is one that seems more precise and clearer than all the others. In order that men remain civilized or become so, the art of associating must be fully developed and perfected among them.”

5Of special relevance in this set of citations is Theodore Newcomb’s “Bennington Studies” (Alwin et al. 1991; Newcomb 1943; Newcomb et al. 1967). Like Newcomb, I assess the socializing effect that college life has on young adults.

18 |

Chapter 2 |

With regard to research specifically on civic talk, a number of works have examined the relationship between political discussion and civic participation (Campbell and Wolbrecht 2006; Huckfeldt and Sprague 1991, 1995; Huckfeldt et al. 1995; Kenny 1992, 1994; Lake and Huckfeldt 1998; McClurg 2003, 2004; Mutz 2002). These studies suggest that civic talk has an influence on how individuals view and participate in politics. For example, using a national survey of the United States, Lake and Huckfeldt (1998) show that the amount of political discussion occurring in an individual’s social network correlates with his or her level of political participation, even after controlling for a host of alternative explanations. Beyond showing a positive relationship between civic talk and civic participation, more recent works on social networks have attempted to identify the mechanisms that allow individuals to translate discussion into action. For example, in an analysis of Huckfeldt and Sprague’s (1995) data set from South Bend, Indiana, McClurg (2003) shows that peers are an important source of information on politics and current events (also see Downs 1957). Information motivates participation because it increases civic competence (the ability to participate) and civic engagement (having an interest in participating in the first place).

Difficulties Producing Evidence of Causation

Based on the large amount of research that has already been conducted on sociological antecedents of civic participation, it is fair to ask why additional study of this phenomenon is needed. While there is a growing body of literature on civic talk and other related sociological phenomena, the vast majority of political scientists have discounted this line of research. Scholars have expressed serious skepticism about the role of civic talk in encouraging civic participation because conclusive evidence of a causal relationship between these two variables has not been found. Causation has not been shown because it is difficult to determine whether the people in our social environment influence us or whether our own patterns of behavior influence how we choose and act with the people around us (Klofstad 2007; Laver 2005; Nickerson 2008).6

An example helps illustrate why it is difficult to show a causal relationship between civic talk and civic participation. Existing works show a

6In reviewing an edited volume dedicated to the study of social networks, one critic even went as far as to say that “few of us really know what to do about implementing rigorous models of complex political interactions with endogenous preferences” (Laver 2005, 934).

Civic Talk and Civic Participation |

19 |

strong correlation between how much a person talks with his or her peers about politics and how active that person is in civic activities (Campbell and Wolbrecht 2006; Huckfeldt and Sprague 1991, 1995; Huckfeldt et al. 1995; Kenny 1992, 1994; Lake and Huckfeldt 1998; McClurg 2003, 2004; Mutz 2002). However, we cannot conclude that a person’s social context is causing him or her to be more civically active with this evidence. One reason is reciprocal causation; an equally plausible explanation for the relationship between talk and participation is that being civically active causes an individual to talk about politics with his or her peers. Another problem is selection bias. Individuals who are more active in civic activities might consciously choose to associate with people who are more interested in talking about politics. Finally, we also need to consider the possibility of endogeneity bias (or, alternatively worded, omitted variable bias). Some factor that we have not been able to be account for could be causing people to both talk about politics and participate in civic activities.

Because of these serious analytical biases, the voluminous political science literature on civic participation has been dominated by theories that focus on individual-level explanations of civic participation. For example, of the thirty-one articles published on civic participation in the American Political Science Review between 2000 and 2009, only four studies directly examined the influence of sociological antecedents.7 Individual-level explanations of civic participation carry more weight in the field of political science because individual-level determinants of behavior are easier to study than social-level factors. Individual-level data are readily available from social surveys such as the American National Election Studies, and standard methods of statistical analysis are well suited to this type of data. In contrast, sociological factors such as civic talk have been relegated to the background of the field because definitive evidence of a causal relationship between social interactions and individual behavior has been hard to come by using existing data sources and methods of analysis.8

7This figure was determined by examining articles whose abstracts contained the following keywords: “civic participation,” “political participation,” or “voter.” The search was conducted with the Cambridge Journals online database, available at http://journals.cambridge

.org.

8A quintessential example of this focus on individual-level characteristics is the Michigan School of political behavior (see, e.g., Campbell et al. 1960). Research in this tradition focuses on partisan identification and other individual-level antecedents and negates the influence of sociological factors (Zuckerman 2004). In fact, the founders of the Michigan School went as far as to say, “By and large we shall consider external conditions as exogenous to our theoretical system” (Campbell et al. 1960, 27).

20 |

Chapter 2 |

Consequently, we are left with an incomplete understanding of participatory democracy.

A Solution: A Quasi-experimental Panel Study

Traditionally, “two-stage” regression models are used to overcome the types of analytical biases described above. In such specifications, the independent variable of interest (in this case, engaging in civic talk) is modeled with instrumental variables that do not correlate with the outcome variable being predicted (in this case, civic participation). This form of analysis is inappropriate for assessing the relationship between political discussion and political participation, however, because it is difficult to identify variables that reliably predict how often one engages in civic talk that are not correlated with one’s level of civic participation.9

If traditional methods for overcoming analytical bias are not an appropriate way to study civic talk, then what is? As illustrated in Table 2.2, one way to get past the biases that have handicapped this line of research would be to conduct an experiment by randomly assigning one group of individuals to be exposed to civic talk (the treatment group) and another group of like individuals not to be exposed to civic talk (the control group). Random assignment to treatment allows us to be confident that the outcomes of the study are actually being caused by civic talk instead of any other observed or unobserved factors.10 Ideally, data on the study population would also be collected over multiple points in time. Panel data further reduce analytical biases if the two phenomena are collected at separated points in time (with talk measured before participation).

But how can we collect data that look like this? A researcher cannot randomly pull people off of the street, force some to engage in civic talk and others not to, and see what happens as these new social networks evolve over time (at least, not very easily). Thus, to execute this research design we need to find a situation that naturally approximates it. Fortunately, such an environment exists: colleges where students are randomly assigned to dormitories.

9However, this type of analysis has been employed when the independent variable of interest is behavior, such as the voting choices of one’s peers, instead of discussion (see, e.g., Kenny 1992).

10Nickerson (2008) uses this type of experimental research design to test whether individuals living in the same household influence one another to vote. However, this study does not examine whether civic talk is the causal mechanism behind civic participation.

Civic Talk and Civic Participation |

21 |

TABLE 2.2 Overcoming analytical biases associated with the study of civic talk

Analytical |

Solution |

Explanation |

C-SNIP execution |

|

problem |

||||

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The individual is no |

|

|

Selection bias |

|

longer able to select |

Study participants |

|

|

|

his or her peer group. |

||

|

Random assign- |

were randomly |

||

|

|

|||

|

ment to peer |

Any explanation of |

assigned to their first- |

|

|

group |

year college room- |

||

Endogeneity |

civic participation that |

|||

|

mate. |

|||

bias |

|

is not accounted for is |

||

|

|

|||

|

|

still orthogonal. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Controlling for past |

Patterns of civic |

|

|

|

patterns of behavior |

||

|

|

participation were |

||

|

Measure patterns |

allows causation to be |

||

|

measured before |

|||

Reciprocal |

of behavior before |

inferred if there is a |

||

and after study |

||||

causation |

and after exposure |

relationship between |

||

participants |

||||

|

to civic talk |

past instances of civic |

||

|

encountered their |

|||

|

|

talk and current |

||

|

|

new peers at college. |

||

|

|

patterns of behavior. |

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

An example of such an environment is the University of Wisconsin, Madison. Random assignment is incorporated into the university’s housingassignment process because students are assigned to first-year college dormitory roommates based on a lottery. Incoming first-year dormitory residents rank the sixteen dormitories in order of where they want to live.11 Students are then “randomly sorted by computer” (University of Wisconsin, Madison, Division of University Housing 2004) to determine the order in which they will be assigned to dormitories. If space is available in the student’s first housing choice at the time his or her name is reached in the randomly sorted list, the student is randomly placed in a room in that dormitory. If space is not available, an attempt is made to place the student in his or her second choice of dormitory, and so on.

To gather information on this population, three surveys were administered between 2003 and 2007: the Collegiate Social Network Interaction Project (C-SNIP) Panel Survey. Survey participants initially completed two survey questionnaires: one at the beginning of the 2003–2004 school

11While this ranking procedure had an effect on the dormitory to which students were assigned, students were still randomly assigned to roommates within that dormitory. Moreover, fixed effects control variables for dormitory assignment, as well as a series of variables that measure why students ranked the dormitories in the way that they did, are included in the analysis.

22 |

Chapter 2 |

year, before they were affected by their college roommates, and a second at the end of the school year. During the first wave of the study, students were asked about their patterns of civic participation during high school. During the second wave of the study, students were asked how civically active they were during their first year of college, as well as about their relationship with their randomly assigned roommates. In the spring of 2007, during their fourth year of college, students who had participated in the 2003–2004 C-SNIP surveys were re-interviewed.

Additional Analytical Precision

via Data Pre-processing

While the process of assigning C-SNIP participants to dormitory roommates was random, these students were allowed to discuss politics and current events with their roommates as much or as little as they wished. Because of this deviation from random assignment, factors that are out of my control could affect both the treatment (the amount of civic talk to which each student was exposed) and the outcome of interest (civic participation) (Achen 1986; Dunning 2008). For example, students who had been active in voluntary civic organizations before they came to college were more likely to discuss politics and current events with their new roommates (r = .19, p < .01). Prior experience participating in voluntary civic organizations also increased subjects’ likelihood of choosing to participate in such activities during their first year of college (r = .37, p <

.01).

A seemingly logical way to address this feature of the data would be to add offending factors such as past patterns of civic participation to the analysis as control variables. Unfortunately, this approach is not a sufficient solution. Including variables in the analysis that are strongly related to both the independent and dependent variables being examined greatly reduces the precision of the analysis (Achen 1986). However, this feature of the C-SNIP study can be accounted for by pre-processing the data with a “matching” procedure (see, e.g., Dunning 2008; Ho et al. 2007a, 2007b, 2007c). Under this procedure, the effect of engaging in civic talk is measured by comparing the civic participation habits of survey respondents who are similar to one another except that one engaged in civic talk and the other did not. By comparing the participatory habits of similar individuals who did and did not engage in civic talk, we can be confident that any observed difference in civic participation between them is

Civic Talk and Civic Participation |

23 |

unrelated to the factors on which the respondents were matched and, as such, is a consequence of civic talk.12 More detail on how this procedure was conducted is included in Appendix C.

Additional Qualitative Evidence

While survey data allow for systematic study of political phenomena, this form of inquiry is limited by the fact that numbers alone cannot give us a full picture of what actually occurs when peers discuss politics and current events. Richer qualitative data are needed to construct a more holistic picture of how civic talk might influence participatory democracy. Therefore, the quantitative findings presented throughout this book are verified with data collected through a series of focus groups that were conducted with the 2007–2008 first-year class of students at the University of Wisconsin, Madison. This group of students is different from the students examined in the panel survey, which allows me to test the claims I am making with the survey data with another case. However, like the C-SNIP Panel Survey participants, the focus group participants were randomly assigned to their first-year dormitories under the same lottery procedure. Thus, while the qualitative and quantitative data presented in this book come from two separate cases, they are comparable cases.

In total, four focus groups were conducted with eight students in each.13 Students were assigned to one of the four groups based on how civically active they had been in high school (“high” versus “low”) and how much civic talk they engaged in with their randomly assigned roommates (“high” versus “low”). Structuring the focus groups in this way allows me to examine not just whether civic talk causes civic participation, but also

12Matching is less precise than in a controlled experiment because the procedure does not account for unobserved differences between individuals who did and did not engage in civic talk (Arceneaux et al. 2006). However, given the extensive set of pre-treatment covariates that were used in the matching procedure (see Appendix C), it is difficult to think of any meaningful unobserved factors that are not accounted for in the analysis. Moreover, unobserved differences between individuals who did and did not engage in civic talk are likely to correlate with observed differences and thus are accounted for by proxy in the matching procedure (Stuart and Green 2008). As such, and given that a true experiment is an extremely difficult (if not impossible) research design to execute for this research question, matching (in concert with panel data and quasi-random assignment to treatment) is arguably a next-best alternative.

13Budget constraints prevented me from conducting more than four groups. Nonetheless, subsequent chapters show that there is striking agreement between the results of the focus groups and the panel survey.

24 |

Chapter 2 |

how the effect might vary from person to person and from peer group to peer group. For example, individuals with prior experience participating in civic activities may be better able to translate civic talk into civic participation than their less experienced cohorts. This and other related questions are addressed in Chapters 5 and 6.

Case Selection and External Validity

In any scientific study, researchers need to be concerned with how representative their findings are vis-à-vis the case or cases that they have selected to study. The number of cases and the method in which they are selected determine how confident we can be in the results that are generated and in how applicable those results are to the wider world. Keeping this in mind, it is necessary to note that the main sources of evidence presented in this book come from two student populations at one university. Nonetheless, the insights we can gain from these data are of broader import to students of participatory democracy for two reasons: for their internal validity (i.e., the ability to make causal inferences) and because collegiate social networks are a “crucial” case of peer influence (i.e., if we are unable to show causation in this case, we are unlikely to find it in other cases).

The Tradeoff between Internal and External Validity

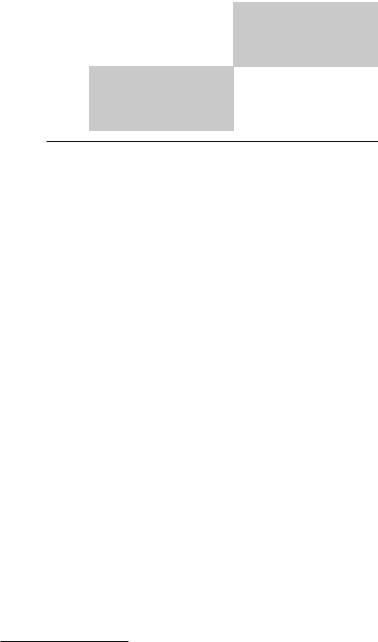

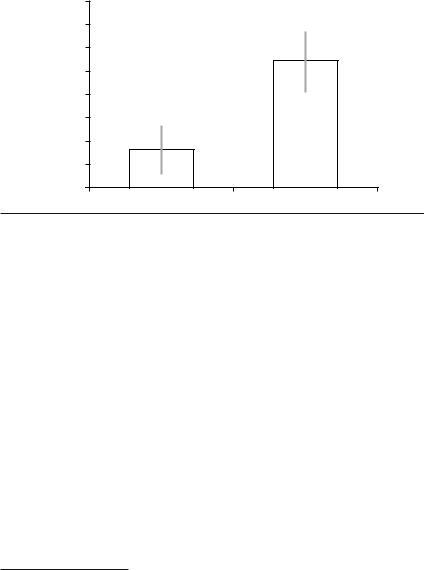

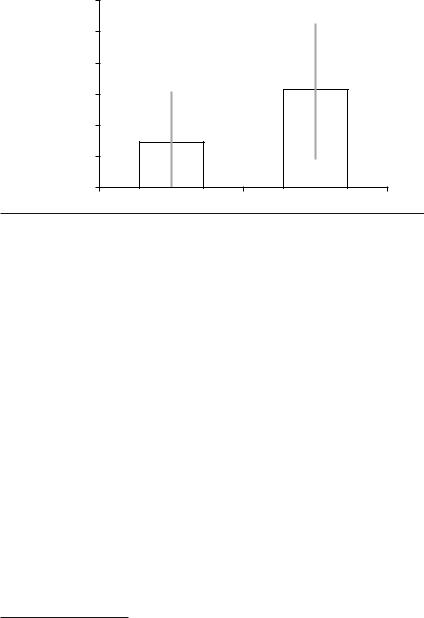

Figure 2.2 illustrates a necessary tradeoff that is made in any scientific study. The figure shows a taxonomy of studies classified on two dimensions: external and internal validity. Ideally, we would like our data to be representative of the entire population in which we are interested (externally valid) while simultaneously allowing us to make definitive claims about causation (internally valid). However, this unique mix of strengths is very difficult, if nearly impossible, to create in one study.

Because it is difficult to maximize both internal and external validity, we are left with the choice of maximizing either one or the other. As addressed earlier, by relying on large-scale social surveys the existing literature on civic talk has already maximized external validity. With these data, we can say with certainty that the types of people who engage in civic talk also participate in civic activities. However, with this type of evidence we have been unable to show that civic talk actually causes civic participation. In response to this persistent problem, I used a different approach to gather the evidence presented in this book: increase internal

Civic Talk and Civic Participation |

25 |

VALIDITY |

High |

EXTERNAL |

Low |

INTERNAL VALIDITY

High |

Low |

|

|

Difficult |

Extant Literature |

|

|

C-SNIP Studies |

Undesirable |

|

|

FIGURE 2.2 Comparing analytic strengths and weaknesses

validity to make more definitive causal claims. The quasi-experimental nature of the data presented in this book allows me to make more reliable causal inferences about the relationship between civic talk and civic participation, an undertaking that had not yet been accomplished.

To restate this point using slightly different language: Those who are critical of research on social networks cannot “have it both ways.”14 On one hand, skeptics have observed that while extant data sets on civic talk are representative of the wider public (i.e., high external validity), these data cannot be used to make causal inferences about social influence (i.e., low internal validity). In this we are in agreement; this persistent problem is what is motivated me to write this book. On the other hand, critics cannot dismiss research solely because of lower external validity when a scholar collects data that can be used to assess causation more accurately. As illustrated in Figure 2.2, the tradeoff between internal and external validity is inevitable. Given that the current goal of social network scholars is (or, at least, should be) to show whether a causal relationship exists between civic talk and civic participation, it is necessary to focus our energy on examining internally valid cases. Once causation is (or is not) established in such cases, we can then tackle issues of external validity by examining additional cases to validate, or reject, previous findings.

College Students as a “Crucial” Case of Peer Influence

In addition to increasing internal validity, the case of first-year college students is also an ideal setting in which to study civic talk because it

14 I thank Scott McClurg for this language.

26 |

Chapter 2 |

represents a “crucial” case of peer influence.15 College is such a case for two reasons. First, college is a “most likely” case of peer influence (Gerring 2001). When a young person leaves his or her family to begin life as an independent adult, peers become highly influential in his or her life (Beck 1977; Campbell et al. 1960). Consequently, we should expect to find evidence of peer effects in this environment. In other words, college is a crucial case to study because if we do not find evidence of a causal relationship between civic talk and civic participation in this environment, we are not likely to find it in other contexts, where peers may be less influential. But if the data presented in this book do show that civic talk has an effect on this collegiate population, we have reason to invest resources in investigating whether this phenomenon occurs in other cases. Possible methods for conducting such further research are discussed in Chapter 8.

In a related vein, a person’s first year of college is also a crucial case because it is a “paradigmatic” case of peer influence (Gerring 2001). A paradigmatic case is one that illustrates the theoretical or conceptual importance of the phenomena being studied. For example, one would not want to study communism without examining the case of the former Soviet Union (Gerring 2001, 219). This case has come to define what communism is and thus is necessary to study when examining that form of governance. In the same vein, collegiate peers define what peer influence is because they are a central facet of the individual’s life as he or she begins adulthood. Moreover, collegiate peers illustrate the importance of peer influence because they are likely to influence the patterns of civic participation that young people carry with them through the rest of their lives. Otherwise stated, and to place this discussion of case selection in a more normative context, steady declines in civic participation over the past half-century have left many wondering whether this dangerous disengagement from public life will continue. If it does, the fate of democracy is in serious peril (Putnam 2000; but see also McDonald and Popkin 2001). Thus, it is incumbent on us to understand how the current generation of young citizens is learning (or not learning) to participate in civic activities. This knowledge will be critically important as scholars and practitioners continue to study and attempt to maintain the strength of civil society.

15Crucial cases are those that are, “for one reason or another, crucial to a concept or to a broader body of theory” (Gerring 2001, 219; see also Eckstein 1975).

Civic Talk and Civic Participation |

27 |

Conclusion

The questions addressed in this book are not new. Because of the critical need for citizens to be involved in the processes of democratic governance, social scientists have always been interested in studying civic participation. Moreover, there is a growing literature on the influence that civic talk within social networks has on civil society. However, the extant literature has not shown a causal relationship between civic talk and civic participation. For this reason, this line of research has been heavily discounted, and our understanding of civic participation is incomplete because it centers on individual-level antecedents of human behavior. Moreover, the inability to establish causation means that second-order questions, such as which causal mechanisms drive the civic talk effect and whether the effect varies under different circumstances, have been understudied.

In response, what is new and innovative in this study is the way I have chosen to gather my data. By leveraging a situation in nature that approximates an experiment, collecting data over time, making use of data preprocessing, and verifying results from survey data with rich qualitative focus group data, I present results in the following chapters that add to our understanding of how participatory democracy works. In the next chapter, I begin this task with a descriptive examination of civic talk and civic participation. I then show that a causal link exists between these two variables.

3

Does Civic Talk Cause

Civic Participation?

Political discussions with roommates and floormates have allowed me to see my own political ignorance and have made me want to read [and] learn more about current events.

—C-SNIP Panel Survey respondent

he experience this student had during her first year in college is a Ttextbook example of what we would see if civic talk has a meaningful effect on how individuals choose to participate in civil society.

The student came to college with a given set of characteristics and patterns of behavior. She was then placed into a new social setting in her dormitory, where the interactions she had with her randomly assigned roommate had an influence on how she looked at and participated in civil society. In other words, engaging in civic talk led the student to have what we could call a civic “awakening,” a moment that led her to become more engaged with the processes of democratic governance.

Chapter 2 introduced the concept of civic talk and showed how quasiexperimental panel survey data and rich qualitative focus group data can be used to overcome analytical biases that have remained unresolved in the literature on civic participation. In this chapter, I use these two data sets to test whether the experience described above is the exception or the rule. I begin by describing how civic participation and civic talk are measured. I then test whether these two phenomena are causally related to each other. The results of the analysis show that civic talk leads individuals to participate in civic activities. These data also show that the magnitude and certainty of the civic talk effect varies based on the civic

30 |

Chapter 3 |

act in question. In short, the evidence shows that civic talk encourages individuals to participate in civic activities, but only in those activities in which they are interested in engaging.

Measuring Civic Talk

The primary measure of civic talk used in this study is based on the C-SNIP Panel Survey question, “When you talk with your roommate, how often do you discuss politics and current events: often, sometimes, rarely, or never?” Use of self-reports is standard practice in this area of research (see, e.g., Campbell and Wolbrecht 2006; Huckfeldt and Sprague 1991, 1995; Huckfeldt et al. 1995; Kenny 1992, 1994; Lake and Huckfeldt 1998; McClurg 2003, 2004; Mutz 2002). An alternative to relying on students’ self-reports about how much civic talk occurred between roommates, however, would be to use a more exogenous measure: the report supplied by each subject’s roommate. This strategy depends on correctly identifying roommate pairs. Based on the small number of subjects who were willing to report their dormitory addresses, only eight-four roommate pairs could be identified. Unfortunately, this sample is not large enough to conduct a thorough investigation of the relationship between civic talk and civic participation. That said, this small amount of data suggests that the use of self-reports is a valid approach. An analysis of the amount of civic talk reported by these roommate pairs shows that roommates agree on how much civic talk they engaged in during their first year of college (t = −1.14, p = .16). Thus, in this population self-reports of civic talk behavior are likely to be observationally equivalent to an exogenous measure of civic talk.

Frequency of Civic Talk

In line with measurements taken in adult populations (see the “What Is Civic Talk?” section in Chapter 2), civic talk is pervasive but not at the top of everyone’s list of discussion topics in the two C-SNIP study populations. On average, C-SNIP Panel Survey respondents reported that they conversed with their randomly assigned roommates somewhere between “sometimes” and “often” (an average of 2.4 on the 0–3 scale ranging from “never” to “often”). In comparison, when specifically asked how often they engaged in civic talk, C-SNIP respondents reported that they participated in these types of conversations somewhere between “rarely” and “sometimes” (an average of 1.4 on the 0–3 scale ranging from “never” to “often”).

Does Civic Talk Cause Civic Participation? |

31 |

Participants in the C-SNIP Focus Group Study painted a similar picture of how frequently civic talk occurred. When asked to list the topics that they discussed with their roommate, politics and current events were always on the list, although never at the top of the list. Instead, classes and course work, music, television shows, celebrity gossip, sports, plans for the future, and dating were among the various discussion topics that were mentioned sooner and more frequently throughout the course of each of the focus group sessions. In addition, when asked to directly compare how often civic talk occurred relative to the discussion of other topics, the vast majority of the focus group participants reported that they discussed politics and current events with their roommate less frequently than other subjects.

Through further discussion, the focus group participants expressed two reasons for why civic talk is less frequent than other types of conversations. One reason is conflict avoidance: In each of the focus groups, the desire to avoid disagreements or arguments with one’s roommate was a common explanation for why civic talk was infrequent, and sometimes actively avoided. This type of exchange was typical in all four of the focus groups:

PARTICIPANT: I think my roommate has the opposite view that I do. I don’t know, because I don’t really talk to her, but I get that impression. So I figure I will just avoid it just to save time so we don’t fight about it or, like, I don’t know, get in a disagreement.

MODERATOR: That’s interesting. So it’s a way to avoid conflict?

PARTICIPANT: Yeah.

Moreover, the focus group sessions revealed that some students would avoid engaging in civic talk even when they had similar political preferences to their roommates’. As one participant stated:

We’re both pretty liberal. But I still disagree with him a lot, and so, like, every once in a while we’ll talk about it. But it’s different between me and, like, a friend where we can talk about it and, like, not get along and then leave and see each other again, and it wouldn’t be that big of a deal. But if you kind of get in, like, a fight with your roommate, it kind of sucks.

Statements of conflict avoidance like these are not, perhaps, very surprising given that these students had an incentive to maintain positive

32 |

Chapter 3 |

relationships with the person they shared small dormitory rooms with for an entire academic year.1

The second most commonly stated reason for why civic talk is not as prevalent as other types of discussions is a lack of interest in politics, either on the part of the individual or on the part of his or her roommate. When directly asked why politics and current events were not frequently discussed, a number of participants in each of the focus groups made statements such as, “My roommate doesn’t like politics,” “It’s almost like a boring topic,” and “Politics usually gets old pretty quickly.” One participant went as far as to say, “My roommate’s more or less mystified by anyone interested in politics.” Another participant summarized his experience by saying, “I asked my roommate once if he was interested in politics or the election or anything, and he said no, so that was the extent of our political conversation.”

Subject Matters and Sources of Civic Talk

Perhaps not surprisingly, the focus groups revealed that civic talk conversations typically occurred in response to current events. A variety of topics were discussed by roommates, including the Iraq war, a student who had recently been murdered near the university campus, the recent election of a student to the City Council, genocide in Darfur, global climate change, and the 2008 presidential primaries. Given that the focus group sessions were conducted in the early spring of 2008, the presidential primaries were the most common topic of conversation. The election was especially in the forefront of conversations between roommates because the State of Wisconsin had just held a presidential primary election on February 19, and each of the major candidates from both parties had held campaign rallies on or near the University of Wisconsin campus. Arguably, the most salient of these events was the large rally held by Barack Obama on February 13, the night of his victories in the “Potomac Primaries” in Virginia, Maryland, and the District of Columbia. The vast majority of the focus group participants reported that they had talked about this rally with their roommates, and many reported having attended (or having attempted to attend) the event.2

1The effect that disagreement has on the relationship between civic talk and civic participation is examined in Chapter 6.

2Senator Obama filled the university’s main indoor stadium to capacity, with more than 19,000 attendees, many of whom were students at the University of Wisconsin, Madison. His main opponent at the time, Senator Hillary Clinton, held a much smaller rally of

Does Civic Talk Cause Civic Participation? |

33 |

Along with highlighting the specific topics discussed when engaging in civic talk, the focus groups revealed two conduits through which politics and current events were brought up during conversations between roommates. One was news media consumption. A majority of the students mentioned that civic talk would occur during normal everyday conversation in relation to what was in the news that day. Statements such as these were common in all of the focus groups:

I would tend to just like read the news on CNN, and so, like, if something pops up usually that I’m opinionated about, then that’s when we starting talking. So it just kind of depends on that.

Well, like, we read the paper, so usually we, like, discuss what’s in the paper.

It usually doesn’t come up unless, like, there’s something [on] TV on it, and then we’re, like, “Oh, that’s kind of interesting,” and then we’ll start talking about it.

The second most often mentioned sources of civic talk were the personal interests and extracurricular activities of individuals and their roommates. Statements such as these were common in each of the focus groups:

We talk a lot more about social issues, too, and like I said before, [my roommate is], like, a really big environmentalist, so she always has something to say about a candidate and what they think about recycling and stuff like that. So we talk a lot about that.

I always talk about Barack Obama, because I’m a huge fan.

We talk a lot about [health maintenance organizations] and doctors and things because she’s going into med[ical] school now as a doctor, so I think we just relate on it. And we talk because I am really passionate about Darfur in Africa, and so we can talk about that.

Measuring Civic Participation

As discussed in Chapter 2, civic participation is a form of activity that pulls an individual out of his or her private life and into civil society. This

approximately 2,000 attendees at an off-campus location on February 18. None of the focus group participants mentioned that they had attended the Clinton event or discussed it with their roommates.

34 Chapter 3

TABLE 3.1 Patterns of civic participation during high school and college

|

Mean activity level |

Percentage inactive |

||

|

High |

1st year |

High |

1st year |

Civic activities |

school |

of college |

school |

of college |

|

|

|

|

|

Participation in voluntary |

|

|

|

|

civic organizations |

|

|

|

|

(0–21 point activity scale) |

6.60 |

2.43 |

5 |

35 |

Participation in political activities |

|

|

|

|

(0–6 point activity scale) |

1.16 |

.56 |

44 |

68 |

Voter turnout (2004 presidential |

|

|

|

|

primary) (%) |

|

51 |

|

49 |

Source: C-SNIP Panel Survey.

Note: As is common in studies of voter turnout, the figures are likely inflated. For example, data from the U.S. Census Bureau’s Current Population Survey show that in the 2004 presidential election, only 47 percent of citizens between eighteen and twenty-four turned out to vote (Faler 2005).

large set of activities can be broken down into two categories: political civic activity and non-political civic activity. The analyses in this chapter examine three such forms of behavior: voter turnout, participation in other types of political activities, and membership in voluntary civic organizations. A summary of how active students in the C-SNIP Panel Survey were in these activities during high school and their first year of college is presented in Table 3.1.

Voter Turnout and Participation in

Other Political Activities

The C-SNIP Panel Survey collected information on two forms of political participation. One measure was derived from how active each student reported being in three different activities: contacting an elected official about an issue, participating in a march or protest, and working for a political campaign at any level of government (including student government campaigns). For each type of activity, students were asked to rate how many times they had participated over the previous year: “never,” “once,” or “more than once.” Participation in these activities was coded as the sum of the three activity scales.

A second measure of political participation was based on each student’s self-reported voter turnout in the 2004 presidential primary. Voting is similar to the other political activities described above in that each of

Does Civic Talk Cause Civic Participation? |

35 |

these acts is motivated by the individual’s desire to influence the government. However, voting is treated separately in this analysis because it is the only behavior that allows citizens to have a direct voice in selecting their leaders. Moreover, despite declines in voter turnout over the past fifty years, voting differs from other political activities because it is the least costly and most widely participated in political act in the United States (Verba et al. 1995, 51).

Non-Political Civic Activity: Participation in

Voluntary Membership Organizations

In total, this analysis accounts for seven different types of voluntary civic group affiliations: charitable and voluntary service; leadership and civic training; groups that “take stands on political issues or current events”; partisan groups; student government; student publications such as newspapers; and speech clubs and teams (e.g., forensics, debate). For each of these types of organizations, students were asked to rate how active they were on a 0–3 point scale, ranging from “not at all active” to “very active.” Participation is coded as the total amount of organizational activity in which each student engaged (i.e., the sum of the seven 0–3-point scales).

These voluntary civic organizations may from time to time engage in politically relevant activities. For example, members of the university’s student government might lobby the state legislature to provide more resources to the university, or a service organization dedicated to helping the homeless might lobby the local government to provide more shelters. Nonetheless, it is important to underscore that the act of participating in one of these voluntary civic organizations is distinct from engaging in one of the political activities described above. As discussed in Chapter 2, voluntary civic associations may be politically relevant. However, they are not classified as political activities because they do not directly influence the processes of governance (i.e., they do not involve citizens explicitly attempting to directly affect decisions made by the government or determine who is selected to run the government by influencing electoral outcomes).

Trends in Civic Participation across Activities

The data in Table 3.1 show that C-SNIP Panel Survey respondents participated in political activities far less frequently than in voluntary civic organizations. Overall, 5 percent of students reported that they had not participated in any voluntary civic membership organizations during high

36 |

Chapter 3 |

school, compared with 44 percent who claimed that they had not participated in any political activities. This trend continued into the first year of college, where 35 percent of students reported not participating in any voluntary organization activities, compared with 68 percent who reported not participating in any political activities.

Participants in the C-SNIP Focus Group Study provided a similar picture of the gap between political and non-political civic participation. When asked to describe the civic participation in which they had engaged during their first year of college, the vast majority of the activities mentioned by the focus group participants were non-political in nature. The one notable exception to this trend, however, was voting. Many of the focus group participants spontaneously mentioned that they had voted in the 2008 presidential primary, and the vast majority of participants reported that they had voted when specifically asked whether they had. As mentioned in a previous section, the majority of the focus group participants also reported that they had attended (or had attempted to attend) the large rally staged by Senator Barack Obama on February 13, 2008. The prevalence of voting and engagement with the 2008 primary elections makes sense, given the close proximity of the Wisconsin primary to when the focus groups were conducted and the broad appeal of the Obama campaign among young people.

Engagement with the 2008 election aside, what explains the sizeable gap between political participation and participation in voluntary civic organizations in these two student populations? A likely explanation for why these students are not politically active is because they are not politically engaged. For example, in the C-SNIP Panel Survey, subjects were asked, “In general, which do you think is the better way to solve important issues facing the country, through political involvement (for example, voting, working for political candidates, and the like) or through community involvement (for example, volunteering in the community, and the like)?” Students vastly preferred community involvement to political involvement in both high school (77%) and during their first year of college (72%).3 Not surprisingly, political engagement and political participation are related to each other. Students who cited “community involvement” as their preferred mode of civic activity were less active in political activities both in high school (t = −2.07, p = .04) and during their first year of college (t = −2.03, p = .05).

3These figures are commensurate with national samples of college students: see, e.g., Harvard University Institute of Politics 2000.

Does Civic Talk Cause Civic Participation? |

37 |

This said, while this student population was politically apathetic, it still adhered to civic-minded norms (for similar findings, see Zukin et al. 2006). For example, while political disengagement correlates with low levels of political participation, panel study respondents were equally likely to participate in voluntary civic organizations in high school (t = −.17, p = .87) and during the first year of college (t = −1.12, p = .27), regardless of whether they cited “political involvement” or “community involvement” as their preferred mode of civic expression. Moreover, when asked in wave 2 of the panel study, “How important do you think it is for people like you to be active and interested in politics and current events: very, somewhat, not very, not at all?” 91 percent of the respondents said that civic participation was somewhat or very important.4 In short, the C-SNIP Panel Survey respondents understood the virtues of participating in civil society. They did not, however, see politics as a desirable venue for such activity.

The focus group participants offered a similar assessment of the gap between political and non-political activity. A number of students mentioned that they were less engaged with politics than with non-political matters. These two comments especially illustrate this attitude:

I’m not exactly really involved in a politically affiliated group as far as, like, a party goes, but I do feel like it’s important to at least represent yourself in a number form [sic] with like humanitarian kind of things.

The reason I don’t get involved in a lot of these political groups, is I think it’s, like, really bureaucratic and not that effective. And as much as I care about it, I really don’t want to, you know, walk around posting fliers or handing out stickers or [sit] in a booth at whatever event. It seems, like, really boring, really boring.

In a similar vein, some students mentioned that they felt unqualified or unprepared to participate in political activities. As one student put it, “We don’t talk about political activities, because we don’t know about anything.” Or, as articulated in this exchange between the moderator and two participants:

MODERATOR: And how about the more political activities?

PARTICIPANT 1: I wish I could get involved in more. It’s just kind of overwhelming at first. There’s just so much stuff going on and

4This question was not asked of students in the high school questionnaire.

38 |

Chapter 3 |

stuff, so I’m interested in politics and stuff and even, like, the other side of politics. I don’t know. Hopefully, next year I’ll be a little bit more involved with that.

PARTICIPANT 2: I like to know what other people think about it, but I don’t know anything about it, so I feel stupid.

Low levels of political participation, engagement, and efficacy are not very surprising, given the relatively young age of the populations examined in the C-SNIP studies. As shown by the high number of politically inactive students reported in Table 3.1, these young people did not have extensive prior experience participating in political activities before coming to college.5 In contrast, the vast majority of the students in the study did have some form of prior experience participating in non-political civic activities—that is, only 5 percent reported that they had not participated in any civic organizations before coming to college, compared with 44 percent who reported that they had never participated in political activities before coming to college. Past patterns of civic behavior are meaningful because civic participation, like any other form of behavior, is habitual (Brady et al. 1999; Burns et al. 2001; Fowler 2006; Gerber et al. 2003; Plutzer 2002; Putnam 2000; Rosenstone and Hansen 1993; Verba et al. 1995). Since the students examined in this study did not gain extensive experience participating in political activities during high school, it is not surprising that they were not very active in or engaged with politics during their first year of college.

Trends in Civic Participation over Time

A second notable trend in Table 3.1 is that this population of students was less civically active during the first year of college than in high school. Data from the focus groups lead to a similar conclusion. When specifically asked to compare how civically active they had been in high school with how active they had been during their first year of college, the vast majority of the focus group participants reported that they had been more active during their high school years.

One explanation for this marked drop in participation between high school and the first year of college is that the first year of college is a period of significant transition in one’s life. After leaving home and family

5This lack of experience is sometimes legally mandated, as in the case of the right to vote being extended at age 18.

Does Civic Talk Cause Civic Participation? |

39 |

for college, young people are forced to adjust to a new and very different lifestyle as independent adults. Consequently, participation in civic activities should be expected to become less of a priority when a person needs to spend his or her time and energy learning how to navigate a new town, make new friends, learn how to study, and the like. Existing research in the fields of higher education, psychology, and political science offer support for this hypothesis. The transition to college has been documented to be a stressful and life-changing process as the student leans how to find his or her place in a new social and academic environment (Boyer 1987; Compas et al. 1986; Cutrona 1982; Takahashi and Majima 1994; Terenzini et al. 1994). Moreover, studies have shown that civic engagement and participation drop during times of transition and relocation (Putnam 2000, 204).

Data from the C-SNIP Panel Survey also offer evidence in support of this hypothesis. For example, in the first and second waves of the study respondents were asked, “How much free time have you had during the average week to participate in the types of organizations you answered questions about at the beginning of this survey: a lot of time, a moderate amount of time, very little time, or no time at all?” Survey participants reported having significantly less free time to dedicate to civic participation during their first year of college than they had in high school (t = −19.22, p < .01). Respondents were also asked, “Generally speaking, how much would you say that you know about politics and current events: a great deal, some, or not much?” Comparing the responses to this question given during the first and second waves of the survey shows that the students felt they were more informed about politics and current events during high school than they had been during the first year of college (t = 7.28, p < .01). In the first and second waves of the panel survey students were also asked, “How many days per week, on average, have you read or watched the news to learn about politics and current events?” Compared with their habits during high school, this population consumed significantly less news about politics and current events during the first year of college (t = −7.36, p < .01).

Do these measures help explain the participation gap between high school and the first year of college? Logically, we would expect that people with less free time would be less civically active. Time is a resource that is requisite for participation in civil society (Putnam 2000; Verba et al. 1995). However, the results in Table 3.2 show that available free time does not correlate with how civically active these students chose to be during their first year of college. The data do show, however, that political

40 |

Chapter 3 |

TABLE 3.2 Free time, political knowledge, media use, and patterns of civic participation during the first year of college (correlations)

|

|

Knowledge about |

News |

|

Free |

politics and |

media |

Civic activities |

time |

current events |

usage |

|

|

|

|

Participation in voluntary civic organizations |

.05 |

.32*** |

.24*** |

Participation in political activities |

.05 |

.31*** |

.30*** |

Voter turnout (2004 presidential primary) |

.05 |

.22*** |

.20*** |

Source: C-SNIP Panel Survey.

***p ≤ .01.

knowledge and news media usage are highly correlated with all three forms of civic participation. For this reason, declines in knowledge and media use between high school and the first year of college help explain declines in civic participation over this same time period.

The idea that civic participation becomes less of a priority as people transition to life on their own at college was also a pervasive theme in the focus groups. Statements such as these were typical throughout the sessions:

In the beginning of the year, I was just kind of stressed with school and getting used to everything here, and I didn’t really pay attention to any of that kind of stuff.

I felt for the first, maybe first, semester, I was completely removed. I stopped reading the news. I was just figuring stuff out and became busy. . . . [I]n addition, . . . a large part of my political involvement was, like, you know, talking with my family at dinner. So mixing that up in a new environment [at college], it really caused me to do a lot less.

At the beginning of the year when we first got here, they had a club fair, but I was just so busy meeting people that I didn’t really think of it then.

While civic disengagement is a satisfying explanation for the drop in participation between high school and college, an additional explanation is the prevalence of service learning opportunities in American primary and secondary schools. These programs lower the costs of civic participation by providing prepackaged opportunities for students to become active. Moreover, the programs can raise the costs associated with not

Does Civic Talk Cause Civic Participation? |

41 |

participating, because participation is often mandated as a requirement for graduation or course credit. Such programs became increasingly popular at the time that the C-SNIP Panel Survey participants were completing elementary and secondary school. On the federal level, these programs started receiving support when President George H. W. Bush enacted the National and Community Service Act of 1990, which created the Commission on National and Community Service (Public Law 101-610). The commission’s main duty was to create and support service learning programs. President Bill Clinton extended federal support for service learning programs by reauthorizing the National and Community Service Act under the National and Community Service Trust Act of 1993 (Public Law 103-82). This legislation merged a number of different agencies focused on civic involvement into the Corporation for National and Community Service. The act also established Learn and Serve America, a program that supports service learning programs.

In response to actions taken on the federal level, the American states have increased their commitment to providing service learning opportunities to school-age children. This has especially been the case in the State of Wisconsin, where 72 percent of the C-SNIP Panel Survey participants attended high school. For example, the state’s Department of Public Instruction established the Cooperative Educational Service Agency to promote service learning programs and to act as a liaison between schools and the federal Learn and Serve America program. The state also allows school districts to “require a pupil to participate in community service activities in order to receive a high school diploma” (Wisconsin Statute 118.33).

In summary, the populations studied in this book completed primary and secondary school as service learning education was growing in popularity across the United States. Moreover, the vast majority of the students had attended high school in a state where service learning is a requirement for graduation. Participating in mandatory service learning programs likely led these students to take part in an abnormally high number of activities during high school because civic activities are easier to engage in when opportunities to act are arranged for you or if sanctions are placed on those who choose not to participate (Olson 1965; Rosenstone and Hansen 1993; Verba et al. 1995). On entering college, these students no longer had built-in incentives to participate. Consequently, it is not surprising that participation levels fell after leaving high school.

The focus group participants corroborated the notion that civic participation was easier to engage in during high school because it was required

42 |

Chapter 3 |

or because structured opportunities were provided. A number of participants made comments such as these:

[I’m] a lot less involved now, I guess, just because in high school it was much more convenient, because it was either before or after class, so you’re already right there. It was just more of a clear-cut commitment.

I miss the structure. I think it’s in a way hurt me. Like, I have a lot of free time, and I don’t know what to do with it.

I think during high school I put more time into it only because I was in government class and we had hours required for that.

In a related vein, a number of students in the focus groups also appeared to be using their time at college to take a break from the civic participation requirements they were obliged to fulfill in high school.

I guess I kind of lost motivation for it. It used to be a mandatory part of my life to volunteer and be a part of things for school or other organizations. But now it’s, like, up to me, and I’d rather not.

I was student council president and stuff like that. I actually had a class hour dedicated to filling out forms and talking to people higher up than me, going and talking to everyone in their school and stuff. And I had to organize one volunteer thing a month and stuff like that. So I was very happy to get rid of all that and have time off from that.

I haven’t done as much this year, but I think it’s more like for my first year, I’m a freshman, and so I just, like, want to get settled in and not have to worry about that stuff as much. I figure I could do it later if I wanted to.

Does Civic Talk Cause Civic Participation?

Survey Evidence

Participation in Voluntary Civic Organizations

To what extent does civic talk influence how active a person chooses to be in civil society? I begin to answer this question with a regression analysis of how active the C-SNIP Panel Survey respondents were in voluntary

Does Civic Talk Cause Civic Participation? |

43 |

TABLE 3.3 The effect of civic talk on participation in voluntary civic organizations during the first year of college (regression analysis)

|

Matched |

Unmatched |

|

(1) |

(2) |

|

|

|

Civic talk |

.81** |

.86*** |

|

(.30) |

(.18) |

Participation in voluntary civic organizations |

.22*** |

.25*** |

during high school |

(.03) |

(.02) |

Constant |

1.67 |

.78 |

|

(1.76) |

(1.20) |

Adjusted R2 |

.13 |

.18 |

Source: C-SNIP Panel Survey.

Model Type: Ordinary least squares (Imai et al. 2007c).

Note: Dormitory assignment fixed effects were included in the analysis but are omitted from the table (none of the coefficients were statistically significant). Standard errors are in parentheses. N = 1,044.

*p ≤ .10; **p ≤ .05; ***p ≤ .01.