5

Do You Matter?

MODERATOR: Do you guys ever talk with your roommates about getting involved in student organizations or political groups?

PARTICIPANT: Yes.

MODERATOR: And what? Can you tell . . .

PARTICIPANT: Well, he mostly talks. He prompts me to get me involved, and I usually tell him I’m not interested.

—C-SNIP Focus Group Study participant

n the preceding chapters, I showed that the people in our social environ- Iment have a meaningful impact on how we choose to participate in the processes of democratic governance. Evidence from a quasi-experimental panel survey and a series of qualitative focus groups shows that, when we discuss politics and current events with our peers, we are more likely to participate in civic activities. This relationship between civic talk and civic participation exists because of resources, engagement, recruitment, and norms. Conversations about politics and current events provide us with information about how to participate in civic activities, enhance our sense of psychological engagement with civil society, subject us to blandishments to participate in civic activities, and lead us to greater acceptance of civic-minded attitudes. Further analysis shows that of these four factors, engagement and recruitment carry the most weight when attempting to

explain the causal link between civic talk and civic participation.

While the preceding chapters have shown that the influence of civic talk on participatory democracy is meaningful, however, we cannot assume that the process of translating civic talk into civic participation will work in the same way in all cases. Two intervening factors need to be considered when studying the effects of engaging in civic talk: our own characteristics and those of our peers. The role of individual characteristics is addressed in this chapter; Chapter 6 examines how the characteristics of our peers affect the relationship between civic talk and civic participation.

72 |

Chapter 5 |

Relying again on the C-SNIP data sets, the evidence presented in this chapter offers a number of insights into how our own characteristics can both enhance and mitigate the influence of civic talk.1 More specifically, the preponderance of the data shows that individuals who are willing and able to participate in civic activities experience a larger boost in their level of civic participation after engaging in civic talk than do their less willing and able counterparts.

Who Should Get More Out of Civic Talk?

Individuals with Weaker Ability to Participate

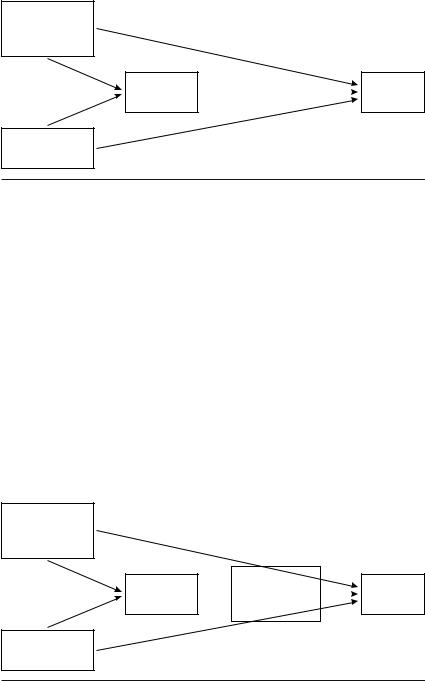

As depicted in Figure 5.1, from the simplest of perspectives, human behavior can be viewed as a product of our personal characteristics (P), our environment (E), and the interaction between these two factors (P × E). Consequently, as P becomes weaker in this model, one’s environment will have more of an influence in determining one’s patterns of behavior. Conversely, as P becomes stronger, the forces in one’s environment will have less influence in determining one’s patterns of behavior. In other words, this model predicts that individuals with weaker predilections to participate in civic activities should be more influenced by discussing politics and current events with their peers.

Research in the field of social psychology offers evidence that supports this hypothesis (see, e.g., Festinger 1954; Marsden and Friedkin 1993; Meyer 1994; Michener and DeLamater 1999; Petty and Cacioppo 1986; Silbiger 1977). For example, in his work on social comparison theory, Festinger (1954) found that human beings have an innate need to compare their own opinions and behaviors to those of the members of their social network. We feel this overwhelming need to compare ourselves with our peers to verify that our actions and attitudes are “correct.” Moreover, through their development of the Elaboration Likelihood Model of persuasion, Petty and Cacioppo (1986) found that individuals are more likely to mimic the attitudes and behaviors of their peers when their own attitudes are uncertain. In short, what these and other studies suggest is that individuals with less ability and less desire to participate in civic activities will be more likely to be influenced by their social network of peers.

1Individual-level characteristics also intervene in how social networks affect their members in non-human animals (see, e.g., Pike et al. 2008).

Do You Matter? |

73 |

Personal

Characteristics

(P)

Interaction |

|

Human |

(P×E) |

|

Behavior |

Environment

(E)

FIGURE 5.1 A simple model of human behavior

Individuals with Stronger Ability to Participate

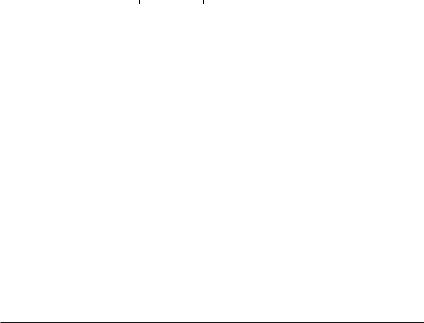

While research in social psychology implies that individuals with weaker ability and desire to participate in civic activities will be more affected by civic talk, the opposite could be true if we take into consideration how individuals weigh the costs and benefits associated with their actions. To account for this facet of decision making, Figure 5.2 complicates the model presented in Figure 5.1 by breaking down the process of human behavior into two stages: a data gathering phase and a data analysis phase. In the data gathering phase, as originally depicted in Figure 5.1, people collect information about how to behave from themselves and from their environment. However, to act on the data they have gathered, Figure 5.2 shows

Data Gathering Phase |

Data Analysis Phase |

Personal

Characteristics

(P)

Interaction |

|

Consideration |

|

Human |

|

of Costs and |

|

||

(P×E) |

|

|

Behavior |

|

|

Benefits |

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Environment

(E)

FIGURE 5.2 Modified simple model of human behavior

74 |

Chapter 5 |

that people will first weigh the costs and benefits associated with taking action. In this model, only when costs are low and benefits are high will people choose to act on what they have learned after consulting with themselves and taking cues from their environment (Downs 1957; Olson 1965; Verba et al. 1995).

But what determines the costs and benefits associated with participating in civic activities? As discussed in Chapter 4, the extensive body of literature on civic participation has come to a consensus that individuals are not automatically equipped to participate in civil society. Instead, a person needs a number of different resources and motivations to participate in civic activities. For example, Verba and his colleagues (1995) show that a person will find the costs of participating in civil society low enough, and the benefits high enough, when he or she is equipped with resources (time, money, and civic skills), has a sense of psychological engagement with politics and current events, and has been recruited by someone, such as a member of his or her social network, to participate. However, the analyses conducted by Verba and colleagues show that, of these three factors, resources and engagement are the most important in determining whether the benefits of civic participation outweigh the costs. As they state it, “Participation can, and does, take place in the absence of specific requests for activity. In contrast, it is hard to imagine activity without at least a modicum of resources and some political engagement” (Verba et al. 1995, 270). In other words, if we are not willing or able to participate in civic activities, no amount of cajoling by our social network of peers will force us to act.

McClurg (2003) also addresses the question of how personal characteristics might influence the effect of civic talk through an analysis of data on social networks collected in South Bend, Indiana, by Huckfeldt and Sprague (1991, 1995). In line with the social psychology literature, McClurg hypothesizes that individuals with low levels of education will experience more of a participatory boost from civic talk than their more educated counterparts. As he states it, “Social interaction should make up the absence of personal resources and we should see a meaningful increase in the propensity to participate among low status individuals who discuss politics” (McClurg 2003, 457). However, the data from South Bend lead to the opposite conclusion: Less-well-educated individuals actually experienced less of a participatory boost from engaging in civic talk than their better-educated counterparts. In fact, McClurg finds that the civic participation gap between the well educated and the poorly educated actually increases as both groups engage in higher amounts of civic talk (McClurg 2003, 459, table 4).

Do You Matter? |

75 |

In summation, what these and other studies suggest is that individuals need to be equipped with certain personal characteristics to be able to respond to stimuli in the environment. In contrast to the social psychology literature, then, political science research on civic participation predicts that if a person lacks the ability or desire to participate in civil society, civic talk should have less of an effect on his or her patterns of civic participation.

Who Gets More Out of Civic Talk?

Survey Evidence

Previous Experience with Civic Participation

Do our predilections to engage in civic activity mitigate or enhance the effect of engaging in civic talk? To address this question, I start by examining how active C-SNIP Panel Survey subjects were in civic activities before engaging in civic talk (i.e., civic participation in high school). The data show that subjects who participated in civic activities at an above average rate in high school were more civically active during their first year of college (participation in voluntary civic organizations: t = 10.42, p < .01; voter turnout: t = 3.30, p < .01). Thus, past experience might have an intervening influence on the civic talk effect. What is unclear, however, is how an individual’s repertoire of past experience participating in civil society will interact with the amount of civic talk in which he or she engages.

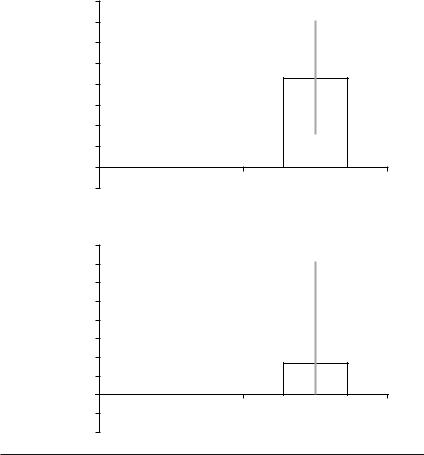

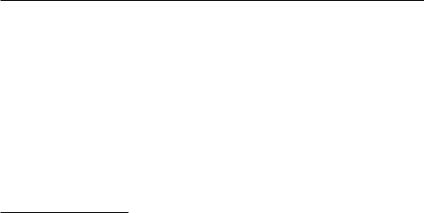

To examine the effect of prior participatory experience on the relationship between civic talk and civic participation, C-SNIP Panel Survey respondents were split into two groups based on how civically active each subject had been in high school, either above average or below average. The regression analysis in Chapter 3 (see Tables 3.3 and 3.5), which showed the causal effect of civic talk on civic participation for the entire pool of C-SNIP Panel Survey respondents, was then conducted separately on the two subsets of respondents. This procedure allows the civic talk effect to be estimated for individuals with above average and below average levels of prior experience participating in civic activities. The results of this analysis are in Figure 5.3.

The data in Figure 5.3 show that prior experience participating in civic activities enhances the relationship between civic talk and civic participation. Focusing on the top portion of the figure, the data show that the effect of civic talk on participation in voluntary civic organizations increases as the individual’s level of prior experience increases. In

76 |

Chapter 5 |

|

Participationin |

2.5 |

|

1.0 |

|

|

|

2.0 |

|

|

1.5 |

|

Change |

0.5 |

|

|

|

|

Expected |

0 |

|

–0.5 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

–1.0 |

Likelihood |

|

0.25 |

|

0.15 |

|

|

|

0.20 |

Changein |

Votingof |

0.10 |

|

|

|

Expected |

|

0.05 |

|

0 |

|

|

|

|

|

–0.05 |

|

Voluntary Civic Organizations

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Below |

Average |

|

Above Average |

|

|||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Prior Participatory Experience

Voter Turnout

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Below |

|

Average |

|

Above Average |

|

|||||

|

|||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Prior Participatory Experience

FIGURE 5.3 The intervening effect of participatory experience on the relationship between civic talk and civic participation

Source: C-SNIP Panel Survey

Notes: The line on each bar represents the 95 percent confidence interval about the estimate. The effect of civic talk is calculated as the level of civic participation estimated to have been engaged in by individuals who were exposed to civic talk, minus that of those who were not exposed, all other factors in the model held at their means.

fact, the civic talk effect is only statistically significant when the student has an above average level of prior experience participating in civic activities. The results in the bottom portion of Figure 5.3 tell a similar story for voter turnout: Only the above average cohort experienced a statistically significant increase in voter turnout due to engaging in civic talk.

Do You Matter? |

77 |

Along with experience participating in civic activities, an individual’s upbringing provides a window into his or her prior experience with politics and current events. The extant literature on political socialization shows that children who were raised by civically active and engaged parents are civically active and engaged as adults (for a summary of this literature, see McIntosh et al. 2007). Data from the C-SNIP Panel Survey corroborate these findings. Subjects raised by parents who were active and interested in politics and current events were also more civically active during their first year of college (participation in voluntary civic organizations: t = 2.81, p < .01; voter turnout: t = 2.42, p = .02).

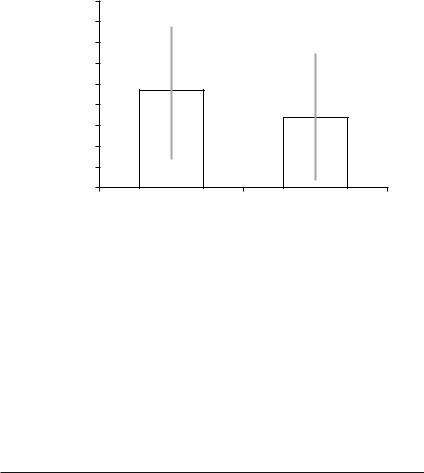

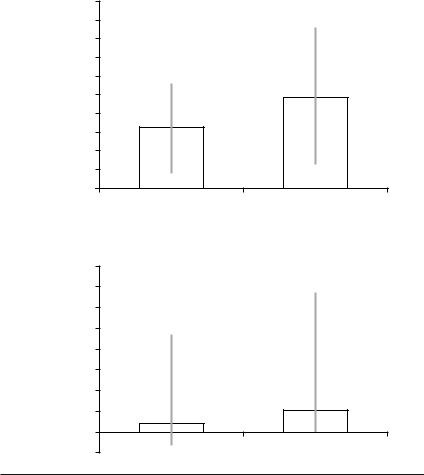

Employing the same procedure used to produce Figure 5.3, Figure 5.4 presents the intervening effect that home life during high school has on the relationship between civic talk and civic participation during the first year of college. These data mirror the results in Figure 5.3.2 The effect of engaging in civic talk on participation in civic organizations and voter turnout is larger for subjects who grew up with parents who were interested and active in politics and current events. In fact, only subjects who were exposed to above average levels of parental civic interest or activity at home before coming to college experienced a statistically significant increase in civic participation due to engaging in civic talk during the first year of college.

Further analysis of the data presented in Figure 5.4 shows that there is a gendered component to the relationship between home life during high school and patterns of civic participation in college. For example, the relationship between the total amount of parental civic activity and interest to which one was exposed (pooling mother’s and father’s activity and interest, as was done in Figure 5.4) and one’s level of participation in voluntary civic organizations during the first year of college is roughly the same for male and female students (male students: r = .09, p = .10; female students: r = .08, p = .04). However, when this result is broken down by gender of parent, we see that these students were more likely to be affected by the parent who shared their gender. More specifically, male respondents appeared to be more likely to mimic the attitudes and behaviors of their fathers than those of their mothers (father: r = .11, p = .06; mother: r = .03, p = .62), while female respondents appeared to be more responsive to their mothers than to their fathers (father: r = .05, p = .18; mother: r = .10, p = .01).

2Similar results are found when examining how much civic talk each subject was exposed to in the home before coming to college.

78 |

Chapter 5 |

Expected Change in Likelihood

Participationin |

1.6 |

|

1.4 |

||

|

||

|

1.2 |

|

|

1.0 |

|

Change |

0.8 |

|

0.4 |

||

Expected |

0.6 |

|

0.2 |

||

|

||

|

0 |

|

|

–0.2 |

|

|

0.16 |

|

|

0.14 |

|

|

0.12 |

|

Votingof |

0.10 |

|

0.04 |

||

|

0.08 |

|

|

0.06 |

0.02

0

–0.02

–0.04

Voluntary Civic Organizations

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Below |

|

Average |

Above Average |

||

|

|||||

Parental Interest and Activity

Voter Turnout

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Below |

Average |

Above Average |

||

Parental Interest and Activity

FIGURE 5.4 The intervening effect of parents’ civic activity and interest on the relationship between civic talk and civic participation

Source: C-SNIP Panel Survey

Notes: The line on each bar represents the 95 percent confidence interval about the estimate. The effect of civic talk is calculated as the level of civic participation estimated to have been engaged in by individuals who were exposed to civic talk, minus that of those who were not exposed, all other factors in the model held at their means.

Civic Engagement

As discussed in Chapter 4, individuals who are interested in politics and current events are more likely to participate in civic activities (Verba et al. 1995). Data from the C-SNIP Panel Survey corroborate this; respondents with above average levels of interest during high school were more

Do You Matter? |

79 |

civically active during their first year of college (participation in voluntary civic organizations: t = 8.80, p < .01; voter turnout: t = 5.37, p < .01). As discussed in the previous chapter, people who feel that their actions will make a difference—those with a sense of efficacy—are also more likely to participate in civil society (Verba et al. 1995). Data from the C-SNIP Panel Survey corroborate this as well; subjects with above average levels of political efficacy during high school were more likely to participate in civic activities in college (participation in voluntary civic organizations: t = 3.87, p < .01; voter turnout: t = 2.48, p = .02).

To test whether civic engagement enhances the effect of civic talk in the same way that prior experience does, the split-sample style of analysis presented in Figures 5.3 and 5.4 was used to take each subject’s level of political interest and efficacy before engaging in civic talk into account. Figure 5.5 shows the intervening effect of prior interest in politics and current events. The results more or less mimic those presented in the previous figures. The higher the subject’s level of interest in politics and current events was before being engaging in civic talk, the larger the effect of civic talk is for participation in voluntary civic organizations. Moreover, the relationship between civic talk and civic participation for individuals with below average levels of civic engagement is not statistically significant. The results for voter turnout in the bottom half of Figure 5.5 are not as conclusive because the effect of civic talk was not statistically significant for the above average half of the sample. However, the data at least suggest a trend of a stronger relationship between civic talk and voter turnout as prior interest in politics and current events increases.

Figure 5.6 (see page 81) tells a somewhat different story for past levels of political efficacy. For participation in voluntary civic organizations, the estimated effect of civic talk is positive and statistically significant in both the below average and above average efficacy cohorts, and the error bars for the two estimates overlap. Thus, these results show that efficacy neither enhances nor mitigates the effect of civic talk on participation in voluntary civic organizations. In contrast, the bottom half of Figure 5.6 shows that the effect of civic talk on voter turnout increases as efficacy increases. Moreover, the civic talk effect is not statistically significant for those individuals with below average levels of political efficacy.

A likely explanation for the difference between the top and bottom portions of Figure 5.6 is that efficacy, as it was measured in the C-SNIP Panel Survey, is more germane to political acts than it is to participation in voluntary civic organizations. The C-SNIP Panel Survey question used to measure efficacy asked respondents, “How much would you agree or

80 |

Chapter 5 |

Expected Change in Likelihood

Participation |

1.8 |

|

1.0 |

||

|

1.6 |

|

|

1.4 |

|

|

1.2 |

|

in |

0.8 |

|

Change |

||

0.6 |

||

|

||

Expected |

0.4 |

|

0.2 |

||

|

||

|

0 |

–0.2

–0.4

|

0.25 |

|

|

0.20 |

|

Voting |

0.15 |

|

0.10 |

||

|

||

of |

0.05 |

|

|

||

|

0 |

|

|

–0.05 |

|

|

–0.10 |

Voluntary Civic Organizations

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Below |

|

Average |

|

Above Average |

|

|||||

|

|||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Prior Political Interest

Voter Turnout

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Below Average |

|

Above |

Average |

|

|||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Prior Political Interest

FIGURE 5.5 The intervening effect of interest in politics and current events on the relationship between civic talk and civic participation

Source: C-SNIP Panel Survey

Notes: The line on each bar represents the 95 percent confidence interval about the estimate. The effect of civic talk is calculated as the level of civic participation estimated to have been engaged in by individuals who were exposed to civic talk, minus that of those who were not exposed, all other factors in the model held at their means.

disagree with this statement: ‘People like me don’t have any say about what the government does?’” Thus, it could be the case that subjects’ attitudes about the government were not important in their decision to participate in non-political student organizations. In contrast, the feeling that one’s actions will (or will not) have a tangible effect on the actions

Do You Matter? |

81 |

Participationin |

1.8 |

|

1.6 |

||

|

||

|

1.4 |

|

|

1.2 |

|

Change |

1.0 |

|

0.6 |

||

Expected |

0.8 |

|

0.4 |

||

|

0.2

0

Likelihood |

|

0.25 |

|

0.15 |

|

|

|

0.20 |

Changein |

Votingof |

0.10 |

|

|

|

Expected |

|

0.05 |

|

0 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

–0.05 |

Voluntary Civic Organizations

Below Average |

Above Average |

Prior Political Efficacy

Voter Turnout

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Below |

Average |

|

Above Average |

|

|||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Prior Political Efficacy

FIGURE 5.6 The intervening effect of political efficacy on the relationship between civic talk and civic participation

Source: C-SNIP Panel Survey

Notes: The line on each bar represents the 95 percent confidence interval about the estimate. The effect of civic talk is calculated as the level of civic participation estimated to have been engaged in by individuals who were exposed to civic talk, minus that of those who were not exposed, all other factors in the model held at their means.

of the government is more logically related to the decision of whether to vote. It is therefore not surprising that political efficacy affects the relationship between civic talk and voter turnout but does not affect the relationship between civic talk and participation in voluntary civic organizations.

82 |

Chapter 5 |

Political Preferences

The strength of one’s political preferences is also an indicator of his or her willingness to participate in civil society (Verba et al. 1995). As with civic engagement, individuals with strong political preferences are more likely to feel the need to participate in civil society. Data from the C-SNIP Panel Survey corroborate this. For example, subjects who reported stronger-than-average ideological identifications in high school were more active in civic activities during their first year of college (participation in voluntary civic organizations: t = 2.37, p < .05; voter turnout: t = 5.47, p < .01).3

But what effect, if any, does this correlation between strength of political preferences and frequency of civic participation have on the effect of engaging in civic talk? To answer this question, Figure 5.7 presents the relationship between civic talk and civic participation for individuals with above and below average ideological preferences. For both participation in voluntary civic organizations and voter turnout, strength of political preferences enhances the effect of civic talk. In fact, the relationship between civic talk and civic participation is not statistically significant for individuals who adhered to weaker political preference before engaging in civic talk.4

The results in Figure 5.7 document the intervening effect of the strength of one’s political preferences, but what about the direction of those preferences? Do liberals experience a larger boost in civic participation than conservatives after engaging in civic talk, or do conservatives get more out of civic talk than liberals? Or is civic talk “value-free,” in the sense that liberals and conservatives experience similar effects after engaging in such discussions?

These questions are of special importance to the C-SNIP study and the case of the University of Wisconsin, Madison. Throughout history, the State of Wisconsin and the University of Wisconsin, Madison, have adhered to a culture of progressive political thought.5 This culture is reflected in the C-SNIP Panel Survey data. On a five-point scale, running from “very conservative” to “very liberal,” subjects on average scored 3.4 during their first year of college (moderate, yet leaning toward the liberal side of the

3Similar results appear in an analysis of strength of partisan identity.

4Similar results appear in an analysis of strength of partisan identity.

5This tradition is exemplified by prolific political leaders such as the Progressive Party’s “Fighting Bob” La Follette and by dark moments in history, such as the violent Vietnam War protests on the University of Wisconsin, Madison, campus during the late 1960s and early 1970s (Bates 1993).

Do You Matter? |

83 |

Expected Change in Likelihood

Participation |

2.0 |

|

1.5 |

||

|

||

in |

1.0 |

|

|

||

Change |

0.5 |

|

Expected |

0 |

|

|

||

|

–0.5 |

|

|

0.20 |

|

|

0.15 |

|

Voting |

0.10 |

|

0.05 |

||

|

||

of |

0 |

|

|

–0.05

–0.10

–0.15

Voluntary Civic Organizations

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Below |

Average |

|

Above Average |

|

|||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Prior Ideological Strength

Voter Turnout

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Below |

Average |

|

Above Average |

||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Prior Ideological Strength

FIGURE 5.7 The intervening effect of strength of ideological preferences on the relationship between civic talk and civic participation

Source: C-SNIP Panel Survey

Notes: The line on each bar represents the 95 percent confidence interval about the estimate. The effect of civic talk is calculated as the level of civic participation estimated to have been engaged in by individuals who were exposed to civic talk, minus that of those who were not exposed, all other factors in the model held at their means.

spectrum).6 Moreover, the more liberal C-SNIP subjects were before they came to college, the more civically active they were during the first year of college (participation in voluntary civic organizations: r = .05, p = .08; voter turnout: r = .16, p < .01).7 The fact that the correlation between

6Similar results appear in an analysis of partisan identity.

7Similar results appear in an analysis of partisan identity.

84 |

Chapter 5 |

Participation |

2.0 |

|

1.8 |

||

|

||

|

1.6 |

|

|

1.4 |

|

in |

1.2 |

|

|

||

Change |

1.0 |

|

0.8 |

||

|

||

Expected |

0.6 |

|

0.4 |

||

|

||

|

0.2 |

|

|

0 |

Likelihood |

|

0.16 |

|

|

0.10 |

||

|

|

0.14 |

|

Changein |

Votingof |

0.12 |

|

0.08 |

|||

|

|

||

|

|

0.06 |

|

Expected |

|

0.04 |

|

|

0 |

||

|

|

0.02 |

|

|

|

–0.02 |

Voluntary Civic Organizations

Conservative |

Liberal |

Subject’s Ideology

Voter Turnout

Conservative |

Liberal |

Subject’s Ideology

FIGURE 5.8 The intervening effect of ideology on the relationship between civic talk and civic participation

Source: C-SNIP Panel Survey

Notes: The line on each bar represents the 95 percent confidence interval about the estimate. The effect of civic talk is calculated as the level of civic participation estimated to have been engaged in by individuals who were exposed to civic talk, minus that of those who were not exposed, all other factors in the model held at their means.

liberalism and civic participation is stronger for voter turnout than for participation in voluntary civic organizations makes sense because the liberal–conservative ideological spectrum is more germane to the realm of politics than it is to non-political civic activity.

Do You Matter? |

85 |

Does the correlation between liberalism and civic participation in the C-SNIP Panel Survey population affect the relationship between civic talk and civic participation? In the same mode as the previous split-sample analyses, Figure 5.8 breaks out the estimated effect of engaging in civic talk on civic participation for liberals and conservatives.8 The top portion of the graph shows that liberals and conservatives alike experienced a significant increase in participation in voluntary civic organizations. In contrast, the bottom portion of Figure 5.8 shows that civic talk does not have a significant effect on voter turnout among conservatives but does among liberals. Mirroring the results for political efficacy presented in Figure 5.6, then, these results shows that ideology plays an intervening role in the relationship between civic talk and the explicitly political act of voting, but not between civic talk and participation in non-political voluntary civic organizations.

Knowledge and Education

One final factor that may affect the relationship between civic talk and civic participation is civically relevant knowledge. Individuals who are more knowledgeable about politics and current events are better equipped, and feel more need, to participate in civic activities (Verba et al. 1995). Data provided by the C-SNIP subjects verify this. Individuals who were more knowledgeable about politics and current events before coming to college were more civically active in college (participation in voluntary civic organizations: t = 6.88, p < .01; voter turnout: t = 3.26, p < .01).9

The results in Figure 5.9 show that knowledge about politics and current events affects the relationship between civic talk and civic participation. However, instead of individuals with higher levels of knowledge experiencing a larger civic talk effect, subjects with below average levels of knowledge appeared to experience a larger and more statistically reliable bump in civic participation after engaging in civic talk.10 With regard to participation in voluntary organizations, the civic talk effect is only statistically significant among those with below average levels of knowledge. With regard to voter turnout, the effect of civic talk on those with

8Similar results appear in an analysis of partisan identity.

9Similar results occur if one examines news media usage in high school as a proxy for knowledge about politics and current events.

10Similar results occur if one examines news media usage in high school as a proxy for knowledge about politics and current events.

86 |

Chapter 5 |

Expected Change in Participation

Change in Likelihood |

of Voting |

Expected |

|

Voluntary Civic Organizations

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Below Average |

|

Above |

|

Average |

|

|||||

|

|||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Prior Knowledge about Politics and Current Events

Voter Turnout

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Below Average |

Above |

Average |

|||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Prior Knowledge about Politics and Current Events

FIGURE 5.9 The intervening effect of knowledge on the relationship between civic talk and civic participation

Source: C-SNIP Panel Survey

Notes: The line on each bar represents the 95 percent confidence interval about the estimate. Figures are based on the matched data regression analyses in Tables 3.3 and 3.5. The estimated effect of civic talk on civic participation is calculated as the level of civic engagement estimated to have been engaged in by individuals who were exposed to civic talk, minus that of those who were not exposed, all other factors in the model held at their means.

below average knowledge is relatively large but falls just outside the minimal threshold of statistical significance (p = .14). In contrast, the effect of civic talk on voter turnout among those with above average knowledge is relatively small and does not come close to a recognized

Do You Matter? |

87 |

level of statistical significance (p = .98). Consequently, contrary to the results presented thus far in this chapter, the evidence in Figure 5.9 is more in line with the expectations of social psychology scholars that individuals with less civically relevant knowledge will be more influenced by their social environment.11

It is also worth examining the potentially intervening effect of education. Educational attainment works in the same way as knowledge about politics and current events: Those with more of it tend to engage in more civic activity (Lake and Huckfeldt 1998; Verba et al. 1995). While the students in the C-SNIP Panel Survey were at the same level of education when the surveys were administered, variance in academic achievement can be assessed by examining the educational background of respondents’ parents, under the assumption that the educational attainment of parents affects the educational prospects of offspring (Croll 2004; Gimpel et al. 2003).

While parents’ education does not correlate with how civically active C-SNIP participants were during their first year of college (participation in voluntary civic organizations: t = −1.35, p = .19; voter turnout: t = −.54, p = .54), the results in Figure 5.10 show that it can play an intervening role in the relationship between civic talk and civic participation. As with civically relevant knowledge, subjects who were raised by parents with below average levels of education appear to have gained more from civic talk than those raised by better-educated parents. In light of the results in Figure 5.9, however, this is not surprising because subjects who were raised by less-well-educated parents were less knowledgeable about politics and current events when they arrived for their first year of college (t = −1.96, p = .05).

Who Gets More Out of Civic Talk?

Focus Group Evidence

In short, the qualitative focus group data also show that individuals with greater ability and desire to participate in civic activities are more affected by engaging in civic talk. As discussed in Chapter 4, the focus groups showed that recruitment attempts during civic talk conversations were only effective when a student has some basic level of interest in becoming

11These results echo the focus group data presented in Chapters 3 and 4, which show that the majority of civic talk conversations center on sharing civically relevant knowledge—that is, facts and opinions about politics and current events, typically in response to what is being covered in the news media.

88 |

Chapter 5 |

|

Participation |

2.0 |

|

1.5 |

|

|

|

|

|

in |

1.0 |

|

|

|

|

Change |

0.5 |

|

Expected |

0 |

|

|

|

|

|

–0.5 |

Likelihood |

|

0.25 |

|

0.15 |

|

|

|

0.20 |

Changein |

Votingof |

0.10 |

|

|

|

Expected |

|

0.05 |

|

0 |

|

|

|

|

|

–0.05 |

|

Voluntary Civic Organizations

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Below Average |

|

Above |

|

Average |

|

|||||

|

|||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Parents’ Education

Voter Turnout

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Below Average |

|

Above |

Average |

|

|||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Parents’ Education

FIGURE 5.10 The intervening effect of parents’ educational attainment on the relationship between civic talk and civic participation

Source: C-SNIP Panel Survey

Notes: The line on each bar represents the 95 percent confidence interval about the estimate. The effect of civic talk is calculated as the level of civic participation estimated to have been engaged in by individuals who were exposed to civic talk, minus that of those who were not exposed, all other factors in the model held at their means.

active in civil society. As one student said, in response to being asked whether civic talk with his roommate caused him to participate in civic activities, “I want to get involved, but sometimes I just lose my motivation. Either I don’t care enough or I would much rather waste my time doing other things.”

Do You Matter? |

89 |

Conclusion

This chapter examined the intervening role that one’s characteristics have in the relationship between civic talk and civic participation. The extant literature suggests two competing hypotheses. Social psychologists suggest that individuals with weaker participatory predilections should be more affected by their social setting. In contrast, political science research on civic participation shows that individuals are not automatically equipped to participate in civil society. Thus, the influence of the social network is expected to be larger when the individual has the desire and ability to participate in civic activities.

The majority of the evidence presented in this chapter shows that individuals who are predisposed to participate in civil society before engaging in civic talk get a larger participatory boost out of engaging in civic talk with their peers. In fact, in most cases, the effect of engaging in civic talk is not statistically significant among those individuals who are less predisposed to engage in civic activities. The two notable exceptions are knowledge about politics and current events and parents’ levels of education. In these cases, individuals with below average knowledge and who were raised by parents with below average levels of educational attainment actually gained more from talking to their peers about politics and current events. So in some cases, the effect of civic talk promotes civic participation among individuals who might not do so unless they are pushed into it by their social network of peers.

This said, from a normative perspective the results presented in this chapter should serve as a cautionary example to scholars of social influence. In this current era of civic engagement in the United States, some have argued that increased social connectedness may be a means by which to revive civil society. For example, Putnam (1994, 2000) found that communities with higher levels of societal interaction and connectedness have higher levels of citizen involvement in public affairs and, as a consequence, are governed more effectively. In the same spirit, the data presented throughout this book confirm that a causal link exists between interpersonal interaction and the strength of participatory democracy. However, the evidence in this chapter shows that, by and large, only those of us who are predisposed to be civically active reap the benefits of engaging in civic talk. Thus, these results suggest that civic talk is not a panacea for civic disengagement. This issue, and the broader question of how we might use social networks to maintain and strengthen participatory democracy, will be given deeper consideration in Chapter 8.