- •Series Editor’s Preface

- •Contents

- •Contributors

- •1 Introduction

- •References

- •2.1 Methodological Introduction

- •2.2 Geographical Background

- •2.3 The Compelling History of Viticulture Terracing

- •2.4 How Water Made Wine

- •2.5 An Apparent Exception: The Wines of the Alps

- •2.6 Convergent Legacies

- •2.7 Conclusions

- •References

- •3.1 The State of the Art: A Growing Interest in the Last 20 Years

- •3.2 An Initial Survey on Extent, Distribution, and Land Use: The MAPTER Project

- •3.3.2 Quality Turn: Local, Artisanal, Different

- •3.3.4 Sociability to Tame Verticality

- •3.3.5 Landscape as a Theater: Aesthetic and Educational Values

- •References

- •4 Slovenian Terraced Landscapes

- •4.1 Introduction

- •4.2 Terraced Landscape Research in Slovenia

- •4.3 State of Terraced Landscapes in Slovenia

- •4.4 Integration of Terraced Landscapes into Spatial Planning and Cultural Heritage

- •4.5 Conclusion

- •Bibliography

- •Sources

- •5.1 Introduction

- •5.3 The Model of the High Valleys of the Southern Massif Central, the Southern Alps, Castagniccia and the Pyrenees Orientals: Small Terraced Areas Associated with Immense Spaces of Extensive Agriculture

- •5.6 What is the Reality of Terraced Agriculture in France in 2017?

- •References

- •6.1 Introduction

- •6.2 Looking Back, Looking Forward

- •6.2.4 New Technologies

- •6.2.5 Policy Needs

- •6.3 Conclusions

- •References

- •7.1 Introduction

- •7.2 Study Area

- •7.3 Methods

- •7.4 Characterization of the Terraces of La Gomera

- •7.4.1 Environmental Factors (Altitude, Slope, Lithology and Landforms)

- •7.4.2 Human Factors (Land Occupation and Protected Nature Areas)

- •7.5 Conclusions

- •References

- •8.1 Geographical Survey About Terraced Landscapes in Peru

- •8.2 Methodology

- •8.3 Threats to Terraced Landscapes in Peru

- •8.4 The Terrace Landscape Debate

- •8.5 Conclusions

- •References

- •9.1 Introduction

- •9.2 Australia

- •9.3 Survival Creativity and Dry Stones

- •9.4 Early 1800s Settlement

- •9.4.2 Gold Mines Walhalla West Gippsland Victoria

- •9.4.3 Goonawarra Vineyard Terraces Sunbury Victoria

- •9.6 Garden Walls Contemporary Terraces

- •9.7 Preservation and Regulations

- •9.8 Art, Craft, Survival and Creativity

- •Appendix 9.1

- •References

- •10 Agricultural Terraces in Mexico

- •10.1 Introduction

- •10.2 Traditional Agricultural Systems

- •10.3 The Agricultural Terraces

- •10.4 Terrace Distribution

- •10.4.1 Terraces in Tlaxcala

- •10.5 Terraces in the Basin of Mexico

- •10.6 Terraces in the Toluca Valley

- •10.7 Terraces in Oaxaca

- •10.8 Terraces in the Mayan Area

- •10.9 Conclusions

- •References

- •11.1 Introduction

- •11.2 Materials and Methods

- •11.2.1 Traditional Cartographic and Photo Analysis

- •11.2.2 Orthophoto

- •11.2.3 WMS and Geobrowser

- •11.2.4 LiDAR Survey

- •11.2.5 UAV Survey

- •11.3 Result and Discussion

- •11.4 Conclusion

- •References

- •12.1 Introduction

- •12.2 Case Study

- •12.2.1 Liguria: A Natural Laboratory for the Analysis of a Terraced Landscape

- •12.2.2 Land Abandonment and Landslides Occurrences

- •12.3 Terraced Landscape Management

- •12.3.1 Monitoring

- •12.3.2 Landscape Agronomic Approach

- •12.3.3 Maintenance

- •12.4 Final Remarks

- •References

- •13 Health, Seeds, Diversity and Terraces

- •13.1 Nutrition and Diseases

- •13.2 Climate Change and Health

- •13.3 Can We Have Both Cheap and Healthy Food?

- •13.4 Where the Seed Comes from?

- •13.5 The Case of Yemen

- •13.7 Conclusions

- •References

- •14.1 Introduction

- •14.2 Components and Features of the Satoyama and the Hani Terrace Landscape

- •14.4 Ecosystem Services of the Satoyama and the Hani Terrace Landscape

- •14.5 Challenges in the Satoyama and the Hani Terrace Landscape

- •References

- •15 Terraced Lands: From Put in Place to Put in Memory

- •15.2 Terraces, Landscapes, Societies

- •15.3 Country Planning: Lifestyles

- •15.4 What Is Important? The System

- •References

- •16.1 Introduction

- •16.2 Case Study: The Traditional Cultural Landscape of Olive Groves in Trevi (Italy)

- •16.2.1 Historical Overview of the Study Area

- •16.2.3 Structural and Technical Data of Olive Groves in the Municipality of Trevi

- •16.3 Materials and Methods

- •16.3.2 Participatory Planning Process

- •16.4 Results and Discussion

- •16.5 Conclusions

- •References

- •17.1 Towards a Circular Paradigm for the Regeneration of Terraced Landscapes

- •17.1.1 Circular Economy and Circularization of Processes

- •17.1.2 The Landscape Systemic Approach

- •17.1.3 The Complex Social Value of Cultural Terraced Landscape as Common Good

- •17.2 Evaluation Tools

- •17.2.1 Multidimensional Impacts of Land Abandonment in Terraced Landscapes

- •17.2.3 Economic Valuation Methods of ES

- •17.3 Some Economic Instruments

- •17.3.1 Applicability and Impact of Subsidy Policies in Terraced Landscapes

- •17.3.3 Payments for Ecosystem Services Promoting Sustainable Farming Practices

- •17.3.4 Pay for Action and Pay for Result Mechanisms

- •17.4 Conclusions and Discussion

- •References

- •18.1 Introduction

- •18.2 Tourism and Landscape: A Brief Theoretical Staging

- •18.3 Tourism Development in Terraced Landscapes: Attractions and Expectations

- •18.3.1 General Trends and Main Issues

- •18.3.2 The Demand Side

- •18.3.3 The Supply Side

- •18.3.4 Our Approach

- •18.4 Tourism and Local Agricultural System

- •18.6 Concluding Remarks

- •References

- •19 Innovative Practices and Strategic Planning on Terraced Landscapes with a View to Building New Alpine Communities

- •19.1 Focusing on Practices

- •19.2 Terraces: A Resource for Building Community Awareness in the Alps

- •19.3 The Alto Canavese Case Study (Piedmont, Italy)

- •19.3.1 A Territory that Looks to a Future Based on Terraced Landscapes

- •19.3.2 The Community’s First Steps: The Practices that Enhance Terraces

- •19.3.3 The Role of Two Projects

- •19.3.3.1 The Strategic Plan

- •References

- •20 Planning, Policies and Governance for Terraced Landscape: A General View

- •20.1 Three Landscapes

- •20.2 Crisis and Opportunity

- •20.4 Planning, Policy and Governance Guidelines

- •Annex

- •Foreword

- •References

- •21.1 About Policies: Why Current Ones Do not Work?

- •21.2 What Landscape Observatories Are?

- •References

- •Index

302 |

T. S. Terkenli et al. |

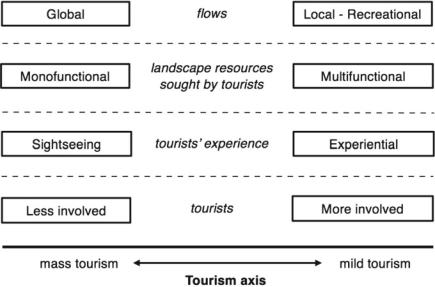

Fig. 18.1 A polarized categorization of types of landscape uses from the demand side of tourism

as complex biophysical and socio-economic systems, worthy of their interest and involvement in and of themselves.

Deeper analysis and a critical approach to the complex relationship of tourism and landscape are, therefore, required, in order to pull out its strengths and weaknesses, as well as its potential and risks. Next, we will focus specifically on the different forms that this relationship may take under various agriculture conditions, in their broader local/regional socio-economic and cultural system.

18.4Tourism and Local Agricultural System

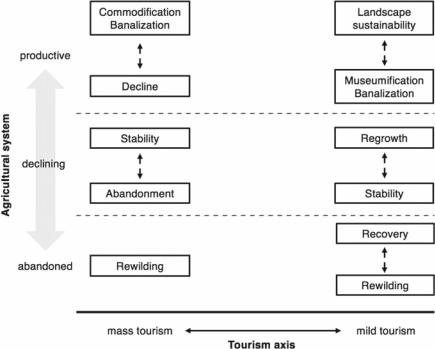

Various types of tourism landscape consumption, as described previously, relate and impact in different ways on the agricultural system, especially according to the type and intensity of agricultural use, ranging from mechanized terrace cultivation to subsistence uses and abandoned terraces. Several questions arise, in this regard: Can tourism be a solution counter terrace abandonment and decline or is it a direct cause of them? Is it even possible to recuperate abandoned and destroyed terraces through tourism? Generalising, how do different forms of tourism produce different impacts on terraced landscapes, in relation to their level of agricultural productivity? The diagram in Fig. 18.2 represents a critical approach to synthesizing the impacts of tourism on the agricultural use of the terraces.

18 The Challenge of Tourism in Terraced Landscapes |

303 |

Fig. 18.2 Impacts of different types of tourism on the agricultural system of terraced landscapes, according to agricultural system capacity

Besides terrace demolition, agricultural mechanization might offer some solutions to terrace maintenance and, at the same time, sustenance of high—or at least competitive—levels of production. Thus, the upper part of the scheme corresponds to the productive terraces, encompassing intense cultivations, run and managed mainly for market destinations, affording enough income for farmers/entrepreneurs, so as to be their one and only occupation, as well as terraces cultivated for local consumption, through cooperative distribution or limited to individual/subsistence uses. A more specific and detailed analysis will, undoubtedly, further distinguish these typological categories of productive terraces, taking into consideration also production techniques, goals and targets.

The second (intermediate) level of agricultural use corresponds to terraces in decline, where a variety of other variables affect the stability of the production. This occurs mainly where crop yields are not especially valuable in terms of farmers’ main source of income, and thus not worthwhile for younger generations to pursue the family’s activity or to invest in new farming technologies. As in the case of the productive (previous) category, this category may also be further split or expanded into more levels and types of decline (structural, economic or social decline).

304 |

T. S. Terkenli et al. |

Finally, the lowest level includes abandoned terraced landscapes, which are often found in the same geographical areas of productive or declining terraces but have been exposed to the least agriculturally favourable conditions, in order for them to continue to be profitably or sustainably exploited. These conditions may refer to the physical realm (morphology, solar irradiation, accessibility of the spot), or to the human/social realm (i.e. economic viability, funding, family characteristics, patterns of land ownership, local development strategies), as explored throughout this volume. On the basis of agricultural use levels, the diagram shows the main impacts under mass or mild tourism conditions–also implying all in-between tourism categories.

Turning now to the bottom-left corner of the diagram (abandoned terraces), we found no bibliographical evidence of any case of terrace restoration from the level of abandonment, strictly due to mass tourism. Therefore, when nearby tourism flows in areas surrounding terraced landscapes, do not consider them as a possible destination, the consequence on the terraced landscape, from the point of view of the agricultural system, is a progressive rewilding, especially in the steepest and mountainous areas. However, moving on the bottom-right part of the diagram, special-interest tourism (such as eco-tourism) has shown to have some potential in the recovery of abandoned terraces, where hiking or climbing-related activities offer incentives to clear and rebuild destroyed drystone walls.

Where agriculture on terraces is in decline, tourism may affect it either in negative or positive ways. In some Greek islands, under strained agricultural conditions, 3Ss tourism may be highly stressful to terraced landscape dynamics (Petanidou et al. 2008; Kizos and Koulouri 2006). When mass 3Ss tourism is not interested in the local culture or nature, meanwhile offering more appealing job opportunities for younger generations, vineyards, olive groves and other cultivations are often abandoned (Terkenli 2001; Tsartas 1996).

Alternative or special-interest forms of tourism might, on the contrary, offer some opportunities to farmers, boosting local and regional economies. In these cases, local farmers are often encouraged to rediscover ancient agricultural practices, and, in combination with modern ones, to provide tourists with high-quality products. Mild, adaptive and sustainable forms of tourism are preferable in these areas, where rural populations are small, services and facilities poor, and accommodations often do not satisfy mass tourism standards and demands, preventing large-scale landscape changes which might compromise ecosystem stability and local cultures survival (Du Cros and McKercher 2015, p. 187; Chan et al. 2016; UNESCO 2008).

Finally, where terraced agricultural systems are highly productive and self-sustained (providing place-based quality products), tourism may impact on the agricultural system mainly in terms of commercial dynamics and with the inclusion of other uses of the terraces along the agricultural one, such as wine and gastronomy tours or cycle tourism. In the case of mass tourism flows, there is a risk that, in order to attract greater tourism demand, terrace cultivation declines due to the dominance of agricultural mechanization and other innovations, leading to the neglect of maintenance of terraced slopes and stonewalls; in these cases, what tends

18 The Challenge of Tourism in Terraced Landscapes |

305 |

to be valued by the tourists are the landscape products, instead of the landscape itself. Other possible impacts might be excessive commodification and banalization of terraced agriculture systems’ characteristics, products and services.

In Valtellina (Italy) for example, traditional vineyards used to be oriented perpendicularly to the terraces, while nowadays they tend to be positioned more in parallel to the terraces, to allow small machines to pass through the cultivated rows. This, of course, constitutes a transformation in the landscape, with a definitive loss, in terms of longstanding traditions and product quality (banalization), but it has allowed farmers to implement innovations and stem the decline of terraced agriculture. In addition, the presence of cycling and walking routes through vineyards allows locals to convey cultural knowledge and expose the value of their products to the tourists. In this case, it seems that agriculture and tourism can benefit from one another, operating as a system of assets which concur towards landscape sustainability. Nevertheless, Puleo (2013) warns about a possible ‘parasitic’ approach, which, on the one hand, through a process of selection and separation, involves the abandonment of terraces not productive or valuable enough, while, on the other hand, through processes of tourist exploitation, relegates the terraces to mere images, for external consumption. In this case, both tourists and tour operators grasp only the scenic dimension of the terraces, their aesthetic value and the impressive effect of the heroic work of generations—accompanied by its appropriate rhetoric—with no further or deeper impact on their knowledge about them or of actual territorial interrelations.

Each of the previous examples is paradigmatic of the main issues that are at stake when agriculture coexists with tourism on the terraces. In general, tourism often seems to conflict with agriculture on terraces, because, here, ecological, social and economic balances are extremely delicate and cannot sustain excessive crowds of visitors. When agriculture survives, it is either in the form of a residual practice, part of the exotic and nostalgic dimension of these landscapes, or it constitutes an innovative activity, as mechanized as possible, and strongly dependent on a market niche, which often uses terraces as a ‘brand’, but tends to ignore or destroy those less productive terraces, just around the corner.

18.5Tourism and the Socio-Economic System

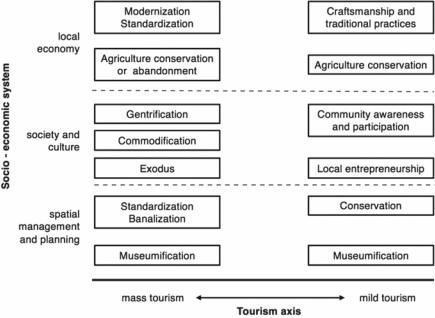

If the impacts of tourism on agriculture affect directly the terraced landscape, the effects of tourism on the broad socio-economic system act mostly indirectly on it, altering it significantly (Fig. 18.3).

As already mentioned, tourism primarily brings about an increase in incomes and jobs, instigating their shift from other economic sectors to tourism itself. These processes occur in different ways, at different destinations, depending on the robustness of the other economic sectors, the types and characteristics of tourism promoters (insiders or outsiders; local small entrepreneurs or large tour operators), the intensity of tourist flows and the type of tourism promoted and developed. Of

306 |

T. S. Terkenli et al. |

Fig. 18.3 Impacts of different types of tourism on the socio-economic system of terraced landscapes

course, when large tourist flows occur, a large shift towards employment in tourism can carry along a decrease of agricultural jobs, especially among the younger population cohorts, with the risk of consequent abandonment of agricultural practices. This is the case in the Philippine rice terraces of the Ifugao region, a UNESCO World Heritage Site, where young people easily and readily find employment in tourism, and traditional know-how of preservation and upkeep of the terraced landscape is no longer transmitted from elderly farmers to the next generations. Such trends may lead to the destruction of the terraced landscape that represents the very basis of the tourist attraction (Christ 2015). In other situations, where tourism only partially contributes to the family income, farming may maintain its importance and rural exodus may be curbed, with opposite—positive— effects on the conservation of these terraced landscapes, as already shown.

Furthermore, the direct involvement and participation of indigenous people in various tiers and posts of the local tourism industry, but especially as active investors, entrepreneurs and managers, keep tourism in local hands, which tends to recycle profits and benefits (and costs, also, of course) in the local societies, thus enhancing tourism development and/or prompting more general local and regional development. This direct involvement and control of local tourism by the local side contribute to the continuation of the traditional activities (agriculture, but also craftsmanship), which also serve and support tourism, interlinked, or even creating a multiplier effect in the local/regional economy. The same effect may be achieved