A Dictionary of Archaeology

.pdfskilfully curved inwards to facilitate roofing (probably of timber and thatch). The use of large blocks of stone has led many authorities to describe the temples as MEGALITHIC, even though the stones are carefully dressed and there seems to be no connection with the megalithic tradition of the Atlantic seaboard. The care taken over temple design is revealed by the possible architectural models discovered at Tarxien (limestone carving) and Hagar Qim (terracotta). A love of architectural detail is also apparent in the underground complex of the Hypogeum. Here, a rock-cut temple connected to tombs reproduces in high-relief carving the lintels and orthostats of the surface temples; the monument performed a funerary role in its final phases but may not have been constructed with that intention. The Hypogeum has preserved wall decoration in the form of painted spirals. Many of the surface temples must also have been plastered and painted, while others are still adorned with simple ‘area pitting’ and low-relief carvings. The most striking carvings are of beautifully balanced spiral designs; at the late temple of Tarxien there are also simple animal friezes. The Maltese monuments are believed to have been temples partly because they contain no evidence of burials and partly because interior features (such as decorated stone ‘altars’) suggest repeated ceremonies. This theory is corroborated by the surviving half of a giant statue at Tarxien, which seems to represent a hugely corpulent, skirted deity; smaller examples have been found at other temples.

J.D. Evans: The prehistoric antiquities of the Maltese Islands

(London, 1971); D. Trump: ‘Megalithic architecture in Malta’ The megalithic monuments of Western Europe, ed. C. Renfrew (London, 1981), 64–76.

RJA

Malwa Cultural phase in the Indian Deccan region (c.1800–1400 BC), named after the Chalcolithic sites on the Malwa plateau, to the east of the BANAS valley. The Malwa culture is defined by buff or orange-slipped pottery painted in black and dark brown. Painted motifs are typically found on the upper section of vessels, and include linear and triangular geometric designs, along with naturalistic motifs including plants, animals and human figures (Dhavalikar 1979: 238). Settlements were small, consisting of wattle and daub houses, and the inhabitants exploited a range of domesticated plant and animal resources including domestic wheat, barley, lentils and peas, as well as wild deer, fish and domestic cattle and pig. Small quantities of copper tools are known from -

MAN-CH’ENG 375

several Malwa sites, including INAMGAON and

NAVDATOLI.

H.D. Sankalia, S.B. Deo and Z.D. Ansari: Chalcolithic Navdatoli (Pune, 1971); M.K. Dhavalikar: ‘Early Farming Cultures of Central India’, Essays in Indian protohistory, ed. D.P. Agrawal and D.K. Chakrabarti (Delhi, 1979), 229–45 (relevant pages of article, 236–43); ––––: ‘The Malwa Culture in Maharashtra’, Srinidhih: perspectives in Indian archaeology, art, and culture, ed. K.V. Raman (Madras, 1983), 17–21; ––––: The first farmers of the Deccan (Pune, 1988).

CS

Malyan, Tal-i (anc. Anshan) Largest surviving PROTO-ELAMITE site, located in southern Iran to the north of modern Shiraz, which was excavated by William Sumner in the 1970s. The lower strata include the remains of ‘Banesh’-period houses with wall-paintings (Nickerson 1977), dating to the 4th millennium BC. After the 3rd millennium BC it became known as Anshan, and, together with the city of SUSA, it formed the nucleus of the kingdom of ELAM. In the early 7th century BC, after a short period of relative obscurity, the city of Anshan was conquered by Teispes, the son of Achaemenes (the founder of the Achaemenid dynasty) and became an important city of the PERSIAN empire, along with

PERSEPOLIS and PASARGADAE.

J. Hansman: ‘Elamites, Achaemenians and Anshan’, Iran 10 (1972), 101–26; Preliminary reports on the Tal-i Malyan excavations by W. Sumner published in Iran 12–14 (1975–6); J.W. Nickerson: ‘Malyan wall paintings’, Expedition 19 (1977), 2–6.

IS

mammisi (birth-house) Invented Coptic term, literally meaning ‘place of birth’, which was first used by the Egyptologist Jean-François Champollion to refer to the buildings in several Late Period, Ptolemaic and Roman temples (e.g. EDFU and DENDERA), in which the birth of the god was celebrated. It may have its origins in the reliefs concerning the divine birth of the king in temples dating at least as early as the 18th dynasty (c.1550–1307 BC), such as LUXOR and the temple of Hatshepsut at DEIR EL-BAHARI.

E.Chassinat: Le mammisi d’Edfou, 2 vols (Cairo, 1939);

F.Daumas: Les mammisi des temples égyptiens (Paris, 1958);

J.Junker and E. Winter: Das Geburtshaus des Tempels der Isis in Philä (Vienna, 1965).

IS

Man-ch’eng (Mancheng) Han-Dynasty site in the province of Ho-pei, China, where two tombs (M1 and M2), each hewn from the solid rock in a

376 MAN-CH’ENG

hillside 1.5 km southwest of Man-ch’eng-hsien, were excavated in 1968. M1 was the tomb of Liu Sheng, Prince Ching of Chung-shan-kuo (d. 113 BC), and M2, contained his concubine, TouWan (named Chun Hsu). Tomb M1 measured 51.7 m long, 37.5 m wide and 6.8 m high, with an overall volume of 2,700 cubic metres, while the equivalent dimensions in M2 are 49.7 m, 65 m, 7.9 m and 3000 cubic metres. It has been estimated that it would have taken about a year to hollow out M1 with present-day excavation facilities, using a labour-force of 100 men.

The two tombs yielded more than 4000 artefacts, including chariots and horses, a suit of ‘fish-scale armour’ (yü-lin-chia) comprising 2859 lames of perforated wrought iron, jade, pottery, lacquer, bronze vessels, complex bronze articulated joinery, bronze (and some iron) chariot and equine equipment, gold and silver medical implements (for acupuncture?), textile fragments and coins. The bodies were both clothed in jade suits, the larger comprising about 2500 individually shaped pieces, each piece being interlocked with the next by means of gold wire-like thread.

Anon: Man-ch’eng Han-mu fa-chüeh pao-kao [Report on the excavation of the Han tombs at Man-ch’eng] (Peking, 1980); Hua Chüeh-ming: Chung-kuo ye-chu-shih lun-chi

[Collected essays on the history of Chinese metallurgy] (Peking, 1986), 65–70.

NB

Manching One of the largest of the OPPIDA of the late Iron Age, in the vicinity of the Danube in Bavaria, south Germany, which flourished in the 2nd and 1st centuries BC. The earliest stage of the site is known only through a small inhumation cemetery, but it probably began as a small cluster of farmsteads during the middle part of the La Tène (La Tène B). Favoured by its location on a major trade route (attested, for example, by the presence of Mediterranean ceramics from the south and raw amber from the north). Manching developed into a trade and manufacturing centre. By the end of La Tène C it had become one of the most populous centres in western and central Europe. Extensive excavations have revealed streets laid out from east to west, lined with small houses; other structures include longer buildings and buildings enclosed in palisades. Whether Manching qualifies as being ‘proto-urban’ depends largely on how that term is defined: there is some evidence to suggest specialised craft production (high-quality pottery, metal-working, glass-making, amber-working etc), the minting of coins, dedicated craft areas, dedi-

cated ‘shops’ or trading and storage spaces, and semi-organized planning of the settlement layout; there is no evidence to suggest strict planning, public buildings, carefully thought out drainage systems, properly surfaced roads etc. Interestingly, the site is not in an easily defensible location and as late as the end of La Tène C Manching was still an open settlement – though ramparts of the murus gallicus type enclosing c.380 ha were added in La Tène D.

Die Ausgrabungen in Manching, various volumes (Stuttgart, n.d.) [no author cited].

RJA

Manda see SWAHILI HARBOUR TOWNS

mandala Term used by I.W. Mabbett and O.W. Wolters to describe the indigenous states of Southeast Asia. In Indian political philosophy, the mandala was perceived as a circle or polity, surrounded by other such circles. Adjacent circles were seen as enemies, but other mandalas might be fostered as allies. The resultant polities were based more on the notion of the centre manifested by its leader, but with fluid boundaries, than a state with fixed territorial limits. The durability of a mandala depended on the charisma of its leader, and the concept becomes less useful following the establishment of ANGKOR, when a degree of permanence based on a dynastic succession was achieved.

Several variables can be identified in any attempt to understand how such complex centralized polities developed. The first and critical point is that Southeast Asian societies had reached a considerable level of sophistication by the end of the 1st millennium BC. The craft specialization seen in the field of pottery at KHOK PHANOM DI (2000–1500 BC) is further attested at BAN DON TA PHET in the expertise associated with bronze working. Iron forging was also widespread, and some communities, as at NON CHAI, had grown in size to the point that we can easily envisage regional centres of political and economic power. The leaders within such networks encountered new opportunities when both Chinese and Indian contact quickened towards the end of the 1st millennium BC. Those which commanded strategic locations, as on a frequented coast or riverine exchange node, were able to control the flow of a new range of exotic goods and ideas. Glass and etched carnelian beads are the physical evidence, but of equal importance was the selective adoption of political, legal and, above all, religious ideas originating in India.

Saivism, the worship of Siva, was prominent in providing emerging leaders with the means whereby semi-divine status could be obtained. The temples to Siva, and other members of the Hindu pantheon, are prominent in the archaeological record in the middle Mekong polities of the ZHENLA CULTURE, while Buddhism was favoured among the polities of the DVARAVATI CULTURE in the Chao Phraya valley. Leaders also adopted the Sanskrit language in taking exotic names and having commemorative stelae erected to advertise their achievements and status.

The critical role of attracting followers to the court centres provided the challenge of sustaining them with food and water. The drought of the long dry season was overcome by digging large reservoirs and moats around the centres, and these served a dual purpose, since, apart from supplying water and aquatic food, they also symbolized the lakes around Mount Meru, the home of the Hindu gods. If the moats represented the lakes, then the temples within were stone representations of the sacred mount. As the rulers assumed the aura of divinity, so their temples were transformed into personal mausolea, where they were worshipped in life as in death.

The identification of agricultural intensification, quickening exchange, the provision of food for specialist craftsmen and soldiers, religious legitimization and establishment of both a legal code and rights of accumulating tribute allow us some insight into the interrelationships between key variables. The archaeological manifestation of this trend is seen in the many court centres, as at Isnapura, MI

SON, MUANG FA DAET, MUANG SIMA and U

Thong. Archaeology has tended to concentrate on the more visible central temples and sacred precincts at the expense of secular remains. We can therefore not be sure of the extent to which a permanent populace would qualify such centres as urban rather than cermonial centres. Excavations away from the large and obvious surviving remains would contribute to this important issue, but at present we can be assured from surviving Chinese accounts that Isanapura, at least, included a substantial royal palace and population measured in thousands rather than hundreds.

I.W. Mabbett: ‘Kingship at Angkor’, JSS 66/2 (1978), 1–58; O.W. Wolters: History, culture and religion in Southeast Asian perspectives (Singapore 1982).

CH

Manekweni Royal settlement of the Zimbabwe period (see GREAT ZIMBABWE), situated a few kilo-

MAPUCHE 377

metres inland from the Mozambique coastal town of Vilanculos. Paul Sinclair’s work at nearby Chibuene shows that this coastal stretch was the source of glass beads found at Schroda, K2 and MAPUNGUBWE. An occupation of the 12th–13th centuries AD, predating the stone enclosure at Manekweni, may be associated with this trade; the main occupation encompasses both the Zimbabwe and Khami periods. Barker’s faunal analyses showed that cattle made up 40–50% and small stock 30–35% of the bone sample associated with the enclosure, while a commoner midden contained only 16% cattle and 50% small stock. Besides this status difference, no calves and few old beasts were present. Barker’s environmental study suggests that cattle had to be kept some distance away during the dry season because of the tsetse fly and poor surface water. As a result of these findings, Peter Garlake proposed that most Zimbabwe-period sites were temporary pastoral nodes on a transhumance cycle; his interpretation, however, is not supported by Portuguese records, by Shona and Venda traditions or by archaeological data pertaining to settlement organization and political hierarchies.

P.S. Garlake: ‘An investigation of Manekweni, Mozambique’, Azania 11 (1976), 25–47; G. Barker: ‘Economic models for the Manekweni Zimbabwe, Mozambique’, Azania 13 (1978), 71–100; P.S. Garlake: ‘Pastoralism and Zimbabwe’, JAH 19 (1978), 479–93; P.J.J. Sinclair: ‘Chibuene: an early trading site in southern Mozambique’, Paideuma 28 (1982), 150–64.

TH

Mangaasi Pacific pottery style with incised and applied-relief decoration which dates from 2700 BP until about 700 years ago; it is thus contemporary with, and post-dates, the

COMPLEX. It is best known from Vanuatu, but is also known from the Solomon islands, New Caledonia and Fiji. Some of the later assemblages from the Bismarck Archipelago bear some resemblance to this style.

J. Garanger: Archéologie des Nouvelles-Hebrides (Paris, 1972).

CG

Manneans see HASANLU

mano see METATE

Mapuche Modern indigenous group of people in southern central Chile. Ethnoarchaeological studies of the Mapuche have yielded important

378 MAPUCHE

information concerning the delineation and utilization of ritual space, including ceremonial plazas and elite burial mounds and the iconography of material goods in a series of interconnected small chiefdoms. The mechanics of social evolution and change among the Mapuche have considerable bearing on archaeological theory concerning cultural change and the development of complex societies.

T.D. Dillehay: ‘Mapuche ceremonial landscape, social recruitment, and resources rights’, WA 22/2 (1990), 225–41; ––––: ‘Keeping outsiders out: public ceremony, resource rights, and hierarchy in historic and contemporary Mapuche society’, Wealth and hierarchy in the Intermediate area, ed. F.W. Lange (Washington, D.C., 1992).

KB

Mapungubwe Hill Part of a complex of Iron Age sites on the farm Greefswald, N. Transvaal, South Africa (see BAMBANDYALANO). This site is particularly notable for the rich haul of gold objects from a grave on the summit of the hill. Subsequent excavations show that it was occupied initially from the late 10th century AD. The original population was replaced about AD 1100 when earlier structures were burned, Bambandyanalo was abandoned, and new settlement was restricted to Mapungubwe summit and the southern terrace slopes. Stone walling is associated with the hilltop settlement. The ‘gold burial’ evidently belongs to a late stage of the occupation, prior to final abandonment of the site about AD 1200. The economy was based on livestock supported by cultivation of millet, sorghum and beans; iron, copper and gold were smelted on the site, and fine ceramics produced. The site was probably the political centre of a group of dependent settlements engaged in trading networks extending to the east coast. It is probably no coincidence that the decline of Mapungubwe is accompanied by the rise of the Zimbabwe state (see GREAT ZIMBABWE) and a new Arab dynasty at

Kilwa on the coast (see SWAHILI HARBOUR TOWNS).

L. Fouché, ed.: Mapungubwe: ancient Bantu civilization on the Limpopo (Cambridge, 1937); G.A. Gardner: Mapungubwe II (Pretoria, 1963); J.F. Eloff and A. Meyer: ‘The Greefswald sites’, Guide to archaeological sites in the northern and eastern Transvaal, ed. E. Voigt (Pretoria, 1981), 7–22.

RI

Maputo Matola see SILVER LEAVES

marae A combination of rectangular court and raised platform used for ritual purposes in central

Polynesia (southern Marquesas, Tuamotus, Societies, Australs and Cooks). There are variations from island to island, but most marae seem to be late prehistoric, dating from the last few hundred years.

K.P. Emory: ‘A re-examination of the east Polynesian marae’, Studies in Oceanic culture history, ed. R.C. Green and M. Kelly (Auckland, 1970), 73–92; P. Bellwood:

Man’s conquest of the Pacific (New York, 1978), 329–30.

CG

Marajó Large island at the mouth of the Amazon in Brazil, where remains of villages on high artificial platforms, groups of ovens, and large cemeteries of urn burials with elaborate polychrome ceramics have been found, all dating to the Marajoara phase (c.AD 1000–1500). Marajó is currently the focus of an argument concerning the ability of the relatively poor and often seasonally inundated lands to support large sedentary populations. This argument has considerable bearing not only on the reconstruction of Amazon prehistory, but upon political rhetoric and development schemes in the Amazon today.

A.C. Roosevelt: Mound builders of the Amazon: geophysical archaeology at Marajo Island, Brazil (Orlando, 1991); B.J. Meggers: ‘Amazonia: real or counterfeit paradise?’, The Review of Archaeology 13/2 (1992), 25–40.

KB

Marana Platform-mound community of the Hohokam culture, dating to the early Classic period (AD 1100–1300), located in the northern Tucson Basin, southern Arizona. Full-coverage survey directed by Paul and Suzanne Fish of the Arizona State Museum has revealed multiple agricultural technologies and underlined the importance of agave as a food and fibre crop.

S.K. and P.R. Fish and J.H. Madsen: The Marana community in the Hohokam world (Tucson, 1992).

JJR

Marden Massive HENGE monument in Wiltshire, England, radiocarbon dated to 2000 BC. The bank and internal ditch form a 14 ha incomplete oval, punctured by two entrances. The henge encloses the remains of at least one circular timber structure (10.5 m in diameter) and, like nearby Avebury and comparable ceremonial structures at Durrington Walls and Mount Pleasant, it is associated with GROOVED WARE.

G.J. Wainwright: ‘The excavation of a later Neolithic enclosure at Marden, Wiltshire’, A J, 51 (1971).

RJA

Mardikh, Tell see EBLA

Mari (Tell Hariri) Mesopotamian city site, located beside the River Euphrates on the border between modern Syria and Iraq, which was occupied continuously from the Jemdet Nasr period (c.3200–2900 BC) to the Seleucid dynasty (c.305–64 BC). Mari was the principal commercial centre on the trade route between Syria and Babylonia; the Early Dynastic remains include a number of substantial mud-brick buildings identified as temples and palaces, although Margueron (1982: 86) argues that the buildings identified as royal residences by the excavator, André Parrot, may have actually been sanctuaries.

The settlement flourished during the Old Babylonian period (c.1894–1595 BC) and it is to the early part of this phase that the extensive palace complex of Zimri-Lim has been dated. The complex comprises over three hundred rooms, including stables, storerooms, archives and bitumen-lined bathrooms, covering a total area of over two and a half hectares. It was never rebuilt after its destruction at the hands of the Babylonian ruler Hammurabi in c.1759 BC, although ironically this has ensured unusually good preservation, with some of the mud-brick walls still standing to a height of five metres and often bearing fragments of plaster and paintings. One surviving mural depicts

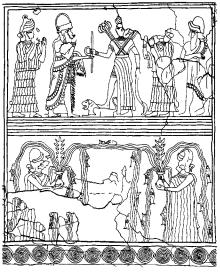

Figure 31 Mari Wall-painting from Mari known as ‘The investiture of Zimri-Lim’, showing the King before the goddess Ishtar and other deities. Source: J. Oates: Babylon, 2nd ed. (Thames and Hudson, 1986), fig. 42.

MARINE ARCHAEOLOGY 379

the ruler of Mari in the presence of various deities, including Ishtar in the form of the goddess of war. An unusual FUNCTIONALIST architectural interpretation has been applied to the palace and its most important courtyard (al-Khalesi 1978).

Undoubtedly the most important discovery in the palace at Mari is the archive of some 23,000 Old Babylonian cuneiform tablets dating from c.1810 to 1760 BC (Dossin et al. 1946–). The cache includes scientific and economic texts, as well as several thousand items of diplomatic correspondence, including a vital set of letters between the ruler of northern Mesopotamia, Shamshi-Adad, and his son, Yasmah-Adad, the ruler of Mari. This archive, still incompletely published, provides enormously detailed information on the society and history of the northern Mesopotamian cities in the 18th century BC.

G. Dossin, J.R. Kupper, J. Bottéro, M. Birot et al: Archives royales de Mari (Paris, 1946–). [ongoing series, currently nearly thirty volumes consisting of transliterations and translations of the cuneiform texts from Mari]; A. Parrot:

Mission archéologique à Mari II: le palais, 3 vols (Paris, 1958–9); ––––: Mari, capitale fabuleuse (Paris, 1974); Y. alKhalesi: The court of the palms: a functional interpretation of the Mari palace (Malibu, 1978); J. Margueron:

Recherches sur les palais mésopotamiens de l’âge due bronze

(Paris, 1982).

IS

Marib see ARABIA, PRE-ISLAMIC

Marietta Earthworks and mound complex located along the Muskingum River in southeastern Ohio (USA), near the confluence of the Muskingum and Ohio rivers (c.200 BC–AD 400). The site consists of two large square earthworks enclosing 20 and 11 ha, respectively. A graded ‘roadway’ extends about 180 m from the west side of the larger earthwork. Several large flat-topped mounds are located inside the larger earthwork, while the smaller one contains four conical mounds. A large conical mound surrounded by a ditch and exterior wall is located just to the east of the smaller square earthwork. The Marietta Works are associated with the Middle

cultural manifestation.

J. Maclean: ‘Ancient works at Marietta, Ohio’, OAHSP 12 (1903), 37–66; G.E. Squier and W.H. Davis: Ancient monuments of the Mississippi Valley (Washington, D.C., 1848 reprinted 1973).

RJE

marine archaeology see MARITIME

ARCHAEOLOGY

380 MARITIME ARCHAEOLOGY

maritime archaeology Study of the material evidence for human activity on the seas and inland waterways. The main concern of maritime archaeology is shipwrecks; other aspects include boat ethnography and experimentation, the recording of submerged coastal structures (such as harbours), and the anthropology of seafaring communities. One specialization, nautical archaeology, primarily concerns ship and boat technology. The term underwater (or at sea marine) archaeology refers to the package of techniques necessary to carry out underwater investigations to the standards of land archaeology.

As well as being complex artefacts of great intrinsic interest, wrecked hulls often contain assemblages of artefacts that offer unique information about seaborne transport. One strength is the typical nature of a wreck as a contemporaneous assemblage that was not consciously pre-selected for discard. It has unusually fine grain, or high resolution and integrity as a body of evidence, owing to the relative homogeneity, respectively, of the events or conditions whose by-products are present in the deposit, and of the agents responsible for those materials. A wreck cargo allows the pottery typologist to establish contemporaneous form variability, and a close date can be obtained from associated finds such as coins. The archaeologist of trade has an unparalleled opportunity to study packaged consumables in transit. In addition to their inferential advantages, wrecks are waterlogged sites that commonly preserve organic materials ranging from timbers to foodstuffs.

Underwater archaeology is conventionally dated from 1960, when George Bass excavated a wreck of the late 2nd millennium BC at GELIDONYA, southwestern Turkey, and demonstrated that scientific wreck investigation was possible (Bass 1966). The major technical breakthrough occurred 18 years earlier, however, when Jacques Cousteau and Emile Gagnan perfected the ‘aqualung’ (or SCUBA: ‘self-contained underwater breathing apparatus’), a regulated compressed-air device that allows untethered access to the maximum safe airdiving depth of about 50 m. The archaeological significance of the first ancient wrecks reported by sport divers, off the south coast of France in the late 1940s, was swiftly recognized, but many sites were looted, and some excavations amounted to little more than salvage. Since 1960, matters have improved, with more diving archaeologists, many high-quality underwater projects world-wide, better protective legislation, and specialist institutes and journals.

Underwater and land techniques of excavation

are fundamentally similar, with adaptations such as air-bags for raising artefacts and air-lifts for removing spoil (Dean et al. 1992). The treatment of waterlogged wreck materials has been at the forefront of archaeological conservation (e.g. Pearson 1987). Underwater fieldwork, however, is typically 8–15 times more expensive than that on land, and time and performance on-site are constrained by depth and conditions. The situation has been improved to some extent by the provision of timesaving survey equipment, such as SHARPS (sonic high accuracy ranging and positioning system), and the use of mixed-gas SCUBA, substituting a different inert gas for nitrogen, which in air-diving becomes dangerously toxic below 50 m and must also be allowed to dissipate from the bloodstream as the diver surfaces. Excavation in abyssal depth may eventually be possible using robots and manned submersibles (Gibbins 1991). Most work, however, will doubtless continue to take place in shallow water, at depths of less than 30 m, where sites are easier to investigate and often provide information comparable with that obtained from deeper wrecks.

The evolution of nautical technology has dominated maritime scholarship, with over a hundred well-preserved hulls excavated worldwide (Steffy 1994). In the Mediterranean, the Ulu Burun wreck (see GELIDONYA), dating to the 14th century BC, demonstrates the early foundation of mortise- and-tenon construction, in which planks were edge-joined and the frames added later. This construction technique is best exemplified by ships of the late Roman Republic (c.150–27 BC), such as MADRAGUE DE GIENS, and it may only have been replaced by wholly frame-first construction a few centuries before the appearance in the Mediterranean of sturdy northwestern European ships such as the cog (13th-century AD). Many wrecks of the Roman Imperial period (c.27 BC–AD 476) are below the minimum acceptable size for seagoing ships inferred from ancient authors, underlining the unreliability of historical evidence for the study of ancient economics and technology (Houston 1988). The socio-economic implications of ship size and shell-first construction – requiring more artistry and labour than frame-first – are now being explored. Also of interest are the sewn hulls of the Archaic Greek period (c.750–480 BC); this technique, easier but less durable, may reflect the scarcity of specialist shipwrights in the ‘Dark Age’ following the collapse of Bronze Age Aegean civilization (Mark 1991).

Ethnography and experimentation

ARCHAEOETHNOGRAPHY and EXPERIMENTAL

ARCHAEOLOGY) have improved understanding of

ship construction and performance, for instance among prehistoric craft of northwestern Europe (McGrail 1987). Omani dhows and Sri Lankan outriggers are among traditional craft that have been recorded (e.g. Kapitän 1991). Full-scale sailing replicas have included a 4th century BC Hellenistic Greek merchantman and a 9th century AD Norse boat (‘Kyrenia 2’ and ‘Gokstad faering’ respectively; see McGrail 1977; Gould 1983: 189–206); other reconstructions have been more conjectural, based on written accounts and artistic depictions, although some cases, such as the reconstruction of a Greek trireme (Morrison and Coates 1986), are very convincing.

Theorists have predominantly addressed the bridge between wreck and ship, part of the maritime variant of MIDDLE-RANGE THEORY (Gibbins 1990). The need for site formation and assemblage analysis is heightened by the ‘fine grain’ of wrecks, their unfamiliarity, and the prevalence of sites in which material is missing or disordered. Pioneering research was carried out by Keith Muckelroy, who developed a methodology based on the ‘scrambling’ and ‘extracting’ effects of the wreck process (Muckelroy 1978). His primary case study for these methods was the Kennemerland, a wreck dating to the 17th century AD for which manifests had survived, making it an excellent example of historical archaeology. At undocumented wrecks, the likely components of shipboard material may be inferred from similar but better-preserved assemblages (e.g. Parker 1992).

Muckelroy’s preservational categories of British wrecks, correlated with variables such as depth, slope and current, have a Mediterranean counterpart (Parker 1980), and have led to work on environmental transforms (e.g. Ferrari and Adams 1990), artefactual contamination (Parker 1981), and the distinction between a scattered wreck and other sites of similar appearance, such as an anchorage or eroded shore deposit (Muckelroy 1979).

Research is increasingly concentrating on the study of trade and the anthropology of seafaring. A particular challenge is the integration of maritime data into a wider archaeological or historical context, and the development of appropriate research strategies. Thus, in the study of Roman amphorae, a cargo is a reflection not only of transport but also of production, packaging and consumption (MADRAGUE DE GIENS). Questions to be asked of wreck data may arise from the complementary investigation of kiln or wharf-side deposits. A recent example is a programme of ceramic

NEUTRON ACTIVATION ANALYSIS in which the

wreck results highlight the organisation of produc-

MARITIME ARCHAEOLOGY 381

tion. Similarly, the material culture of shipboard life may be seen to reflect societal norms of behaviour and expression, as well as the constraints and adaptations of that life-style (e.g. Gould 1983: 37–64).

Another aspect of maritime middle-range theory is the quantification of actual sailings which may be suggested by wrecks, an acute problem if wreck data are to provide a ‘statistics’ of transport. The proportion of known to actual wrecks is a function of the extent of exploration, taking into account searoutes, the relative likelihood of wrecks in shallow waters, and the visibility of different types of cargo in different preservational circumstances. Wreck incidence among unrecorded sailings may be estimated from comparative historical data, if the parameters appear similar; an example is the use of medieval maritime assurance records to gauge wreck incidence.

The most influential theorist in maritime archaeology has been Muckelroy, a Cambridge proponent of NEW ARCHAEOLOGY, whose achievements included a rigorous approach to site evaluation (see above), the application of spatial and statistical analysis, and a systemic model of shipboard dynamics. A group of American anthropologists more explicitly advocated

methods which seek behavioural regularities and underline the cross-cultural similarities of maritime data (Gould 1983). Various attempts have been made to adopt post-processual approaches, includ-

ing CONTEXTUAL ARCHAEOLOGY and FEMINIST

ARCHAEOLOGY (Spencer-Wood 1990) The most important recent development has been the notion of the ‘maritime cultural landscape’ (Westerdahl 1992), stressing the cellular nature and interrelationships of maritime regions, and encompassing the totality of evidence for seafaring, coastal settlement and inland influences; this has given a new focus for general accounts of ships and shipping (e.g. Hutchinson 1994), and a wider context for the study of regional traditions in ship and boat technology (e.g. Westerdahl 1994). The impetus to these developments continues to be the archaeological characterization and publication of sites, including ports and their wrecks (e.g. Marsden 1994), ‘treasure’ wrecks (Marken 1994), recent historic wrecks in the Americas and elsewhere (Bass 1988), and ancient Mediterranean wrecks, which now amount to over 1300 known sites (Parker 1992).

For case-studies see GELIDONYA, MADRAGUE DE

GIENS, and SERÇE LIMAN.

G.F. Bass: Archaeology underwater (London, 1966); S. McGrail: ‘Aspects of experimental boat archaeology’,

382 MARITIME ARCHAEOLOGY

Sources and techniques in boat archaeology, ed. S. McGrail (London, 1977), 23–45; K.W. Muckelroy: Maritime archaeology (Cambridge, 1978); ––––: ‘The Bronze Age site off Moor Sand, near Salcombe, Devon. An interim report on the 1978 season’, IJNA 8 (1979), 189–210; A.J. Parker: ‘The preservation of ships and artefacts in ancient Mediterranean wreck sites’, Progress in Underwater Science

5 (1980), 41–70; ––––: ‘Stratification and contamination in ancient Mediterranean shipwrecks’, IJNA 10 (1981), 309–35; R.A. Gould, ed.: Shipwreck anthropology (Albuquerque, 1983); J.S. Morrison and J.F. Coates: The Athenian trireme (Cambridge, 1986); S. McGrail: Ancient boats in northwestern Europe (London, 1987); C. Pearson, ed.: Conservation of marine archaeological objects (London, 1987); G.F. Bass: Ships and shipwrecks of the Americas

(London 1988); G.W. Houston: ‘Ports in perspective: some comparative materials on Roman merchant ships and ports’, AJA 92 (1988), 553–64; B.J. Ferrari and J. Adams: ‘Biogenic modifications of marine sediments and their influence on archaeological material’, IJNA 19 (1990), 139–51; D.J.L. Gibbins: ‘Analytical approaches in maritime archaeology: a Mediterranean perspective’, Antiquity 64 (1990), 376–89; S. Spencer-Wood, ed.: ‘Stretching the envelope in theory and method’,

Underwater Archaeology: Proceedings from the Society for Historical Archaeology Conference, ed. T.L. Carrell (Tucson, 1990), 20–45; D.J.L. Gibbins: ‘Archaeology in deep water – a preliminary view’, IJNA 20 (1991), 163–8; G. Kapitän: ‘Records of native craft in Sri Lanka’, IJNA 20 (1991), 23–32; S.E. Mark: ‘Odyssey 5.234–53 and Homeric ship construction: a reappraisal’, AJA 95 (1991), 441–5; M. Dean, B. Ferrari, I. Oxley, M. Redknap and K. Watson: Archaeology underwater: the NAS guide to principles and practice (London, 1992); A.J. Parker: Ancient shipwrecks of the Mediterranean and the Roman provinces

(Oxford, 1992); C. Westerdahl: ‘The maritime cultural landscape’, IJNA 21 (1992), 5–14; G. Hutchinson:

Medieval ships and shipping (London, 1994); M.W. Marken: Pottery from Spanish shipwrecks 1500–1800

(Gainesville, 1994); P. Marsden: Ships of the port of London, first to eleventh centuries AD (London, 1994); J.R. Steffy: Wooden ship building and the interpretation of shipwrecks (College Station, 1994); C. Westerdahl, ed.:

Crossroads in ancient shipbuilding (Oxford, 1994); D.J.L. Gibbins: ‘The Roman wreck of c.AD 200 at Plemmirio, near Siracusa (Sicily): fifth interim report’, IJNA 24 (1995); J.P. Delgado, ed.: The British Museum encyclopedia of underwater and maritime archaeology (London, 1997).

DG

Marlik Tepe Early Iron-Age cemetery-site near the Caspian Sea in northwestern Iran, consisting of rich CHAMBER-TOMB burials in which the deceased were often laid on stone slabs. About 20 of the tombs (varying between 2 and 5 m in length) were excavated by an Iranian expedition in 1961–2. The Marlik culture – also known as the Amlash culture after the nearby site of that name – dates to the late

2nd/early 1st millennium BC, and is particularly characterized by gold and silver vessels and jewellery. The grave goods bear certain resemblances to items at contemporaneous ASSYRIAN, Mannean and SCYTHIAN sites.

E.O. Negahban: A preliminary report on Marlik excavation: Gohar Rud expedition: Rudbar 1961–1962 (Tehran, 1964); C.K. Wilkinson: ‘Art of the Marlik culture’, BMMA 24 (1965), 101–9; E.O. Negahban: Metal vessels from Marlik

(Munich, 1983); ––––: Marlik: the complete excavation report, 2 vols (Philadelphia, 1996).

IS

Marpole Type-site of the Marpole culture in the Strait of Georgia region of the northwest coast of North America. This large, deep habitation site, consisting mostly of a SHELL MIDDEN situated at the mouth of the Fraser river in British Columbia, was first investigated around the turn of the century by archaeologists H.I. Smith and Charles HillTout, and then again in the 1950s by Charles E. Borden. The major monograph which defines the Marpole phase and culture by comparison with other sites in the Strait of Georgia region was written by David Burley in 1980.

The eighteen components of the Marpole phase were dated to between 400 BC and AD 400 using a combination of three approaches: MULTI- and Manhattan city block metric distances, based on a

two-dimensional plot of scaled distances, and a set of chronologically-ordered radiocarbon dates. SYS- has also been used to create a model of the development of the Marpole cultural sub-

systems (Burley 1980).

D.V. Burley: Marpole: anthropological reconstructions of a prehistoric Northwest Coast culture type Burnaby, 1980); C.E. Borden: ‘Prehistoric art of the Lower Fraser Region’,

Indian art traditions of the Northwest Coast, ed. R.L. Carlson (Burnaby, 1983), 131–66.

RC

Marquis of Tsai see TS’AI HOU LUAN TOMB

Marxist archaeology Marxists regard each human society as defined and shaped by its MODE OF PRODUCTION, which comprises both ‘forces of production’ (i.e. science, technology and all other human and natural resources) and ‘relations of production’ (i.e. the ways in which people relate to one another in order to facilitate the production and distribution of goods).

Among Western archaeologists, Gordon Childe was famously influenced by Marxist theory, par-

ticularly in the emphasis he placed on the forces of production as the most fundamental influences on prehistoric economies, societies and ideologies. However, his promotion of DIFFUSIONISM as a motor of social advance ran counter to Russian Marxist belief at the time. Childe’s ambivalence prefigured the significant divide that came to exist between ‘Soviet-style’ Marxism and the ‘neoMarxist’ theory employed by some Western archaeologists in the late 20th century (e.g. Spriggs 1984).

Neo-Marxists employ Marxist analysis and concepts without necessarily accepting orthodox Marxist explanations and research priorities. They form a heterogeneous group, although recurring themes in their work include: contradictions between social groups with different relations to the mode of production; contradictions as a motor for social change – often put forward as an antidote to the homeostatic (stabilizing) mechanisms assumed in a purely SYSTEMS THEORY approach to social dynamics; and concern with ideology and symbolism and its relation to economic exploitation and political power. Perhaps the key difference between orthodox and neo-Marxist analysis, mirrored in modern archaeological writing, is the discussion over whether the ‘base’ of any social structure (in essence, the way in which the relations of production are organized) determines, or is simply in dialogue with, the legal and political ‘superstructure’. A central concern of neo-Marxist analysis is the exploration of the latter proposition.

At the same time, the explicitly political content of modern Marxist archaeology is often low, and in the case of many studies the label ‘Marxist’ says more about the intellectual stance of the writer than the content of the research, or even the nature of the interpretation. Furthermore, useful Marxist concepts have been absorbed into a whole range of enquiries that are not explicitly Marxist – notably economic theory, structure, relations between social entities, ideology and symbolism. For example, a combination of Marxism, STRUCTURALISM and anti-positivism is said to have at least partially inspired the emergence of ‘SYMBOLIC ARCHAEOLOGY’ in the 1980s. The idea that symbolic ideologies mask realities, but also actively transform social relations, is one of the more obvious neoMarxist influences. Similarly, archaeological discussions of pre-state social systems often reveal a creative mix of concepts and non-exclusive approaches ranging from neo-Marxism to economic

FUNCTIONALISM and SYSTEMS THEORY. As a final

example, Marxist theorists are keenly aware of the effect of dominant world-views on the shaping of

MASJID AL-JAMIð (ISFAHAN) 383

our views of past peoples; in a more self-critical sense, this has proved to be a key strand of enquiry

in POST-PROCESSUAL ARCHAEOLOGY.

See CHINA 2 for a discussion of the application of Marxist theory to the SHANG culture, and see also

CRITICAL THEORY.

M. Bloch, ed.: Marxist analyses and social anthropology

(London, 1975); S. Frankenstein and M. Rowlands: ‘The internal structure and regional context of Early Iron Age society in south-western Germany’, Bulletin of the Institute of Archaeology, 15 (1978), 73–112; J. Friedman and M. Rowlands, ed.: The evolution of social systems (London, 1978); J. Gledhill: ‘Time’s arrow: anthropology, history, social evolution and Marxist theory’, Critique of Anthropology 16 (1981), 3–30; M. Spriggs, ed.: Marxist perspectives in archaeology (Cambridge, 1984); M. Bloch:

Marxism and anthropology (Oxford, 1985); B.G. Trigger:

A history of archaeological thought (Cambridge, 1989), 212–43, 251–63, 340–7; I.M. Diakonoff and P.L. Kohl, eds: Early Antiquity (Chicago, 1991); I. Hodder: Reading the past, 2nd edn (Cambridge, 1991), 57–79; R.H. McGuire: A Marxist archaeology (New York, 1992).

IS

Masada (Aramaic; mezad, ‘fortress’) Naturally fortified settlement located on a plateau at the edge of the Judaean desert, beside the Dead Sea. It was occupied from at least the Chalcolithic period (c.4000 BC) onwards but it flourished particularly during the Iron Age. Most of the surviving ceremonial buildings and fortifications date to the Hasmonean Dynasty and the period of Roman domination of Syria-Palestine; Herod the Great (c.37–4 BC) constructed a palace complex, like that at the fortress of Herodium, as well as granaries, baths and water cisterns. In AD 73 the site achieved lasting fame as the stronghold in which almost a thousand Zealots committed mass suicide rather than surrender to the 10th Roman Legion; there is good archaeological evidence for the Zealots’ re-use of the Herodian palace, including the construction of a synagogue and a pair of ritual baths (mikvah). The discovery of a cache comprising an ostracon and two Biblical scrolls suggests connections with the Essenes at QUMRAN.

M. Avi-Yonah et al.: ‘Masada, survey and excavations, 1955– 1956’, Israel Exploration Journal 7 (1957), 1–60; Y. Yadin: Masada (London, 1966).

IS

Masjid al-Jamið (Isfahan) Mosque in the Iranian city of Isfahan, the underlying foundations of which were examined during restoration, thus presenting an unusual archaeological opportunity, since Islamic religious concerns tend to prevent ex-

384 MASJID AL-JAMIð (ISFAHAN)

cavation when such buildings are still in use. The core of the standing mosque is Seljuk (11th century AD) and its innovative domed plan was the inspiration of numerous other Seljuk and post-Seljuk mosques in Iran, Anatolia, Egypt and elsewhere. However, excavation revealed the foundations of the 9thand 10th-century Buyid mosque, a period for which monuments in Iran are extremely rare. The excavation showed the proximity of the mosque’s design to those of Iraq and elsewhere in the 9th century and the continuing impact of SASANIAN building techniques in southwestern Iran.

E. Galdieri: Isfahan: Masgid-i Guma 2 vols (Rome, 1972–3).

GK

Masjid-i Suleiman see PERSIA, MAP 28

Maskhuta, Tell el- (anc. Per-Temu Tjeku) Town-site and capital of the 8th nome of Lower Egypt during the Late Period (c.712–332 BC),

N

A

A A

located at the eastern edge of the Delta, 15 km west of modern Ismailiya and the Suez Canal. On the basis of its ancient name, Per-Temu, the site was identified with the Biblical city of Pithom, but more recent excavations (Holladay 1982) have disproved this theory, demonstrating that there was a HYKSOS level below the remains of the city. The late period town was founded by Necho II (c.610–595 BC), and it was still flourishing in the Roman period. The fluctuating importance of the site appears to have been closely linked to the fortunes of the Wadi Tumilat, through which an ancient canal connected the apex of the delta with the Red Sea.

H.E. Naville: The store-city of Pithom and the route of the Exodus (London, 1885); J.S. Holladay, Jr.: Cities of the Delta III: Tell el-Maskhuta (Malibu, 1982).

IS

Mask site Modern Eskimo site in north-central Alaska, studied by Lewis Binford (1978) as part of his ethnoarchaeological work concerning the material culture of prehistoric hunter-gatherers. The site is a hunting stand, where men congregated

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

C |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

1 |

|

|

|

|

C |

C CC C C |

CCCC C |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

|

|

|

|

C |

|

|

|

C |

C |

C C |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

1 |

|

|

|

|

|

C |

|

C |

|

C CC |

CCC CC |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|

CC |

|

|

|

CCC |

C |

C |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

1 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

C |

C C |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

C |

C C |

|

C C |

|

C |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

C C |

|

CC |

CCCC |

C |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

C |

|

|

|

|

|

B D |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

6 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

C |

|

|

|

|

|

|

D |

|

|

|

1 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

A |

|

A |

|

|

|

D |

|

1 1 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

A |

|

A |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

6 |

|

6 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

A |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

6 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

A |

|

4 |

|

4 |

|

|

1 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

A |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

4 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

AA |

|

|

|

|

|

|

4 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

2 |

|

|

|

|

|

A A |

|

|

|

|

|

|

4 |

4 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

9 |

|

|

A A |

A |

ABA |

|

|

|

|

|

4 |

|

|

|

|

5 |

5 |

|

|

|

|

9 |

|

BBBB |

BA |

BB |

|

|

|

|

|

|

4 |

|

|

|

|

5 |

5 |

|

333 |

|

|

9 |

|

BB |

BBBB |

D D |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

5 |

5 |

|

|

|

9 |

99 |

B B BB |

C |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||

5 |

5 |

5 |

|

4 44 |

9 |

9 BB B BBBD |

DD |

|

|

|

|

|

|

B |

|

B |

|||||

|

55 5 5 |

|

2 2 2 4 9 |

|

99 B BB |

DD |

D |

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||

5 |

5 |

5 5 |

|

2 2 2 2 22 |

|

9 |

9 |

BBB |

|

|

D |

|

|

D |

|

|

BBB |

|

|

||

|

5555 5 |

|

3 222 2 222 2 9 |

|

9 B |

|

|

|

D D |

D |

|

DD DDD |

D |

|

|

D |

|||||

|

555 |

|

3 3 322 2 |

2 2 |

9 BBB B |

|

D |

D |

D |

|

DD |

D |

DD |

|

|

D |

|||||

|

|

5 |

3 33 3 2 2 2 22 9 9 9 |

B |

|

|

D |

|

|

DD |

D |

|

|

D |

|||||||

|

|

|

3 33 3 3 2 2 2 2 |

9 B BB BB |

|

|

|

|

DD D |

|

|

D DD |

1 |

||||||||

|

5 |

5 |

3 |

3 3 3 3 3 22 |

|

|

99 |

B |

|

B |

D |

|

|

|

DDD |

D |

|

D |

|

|

|

|

|

5 |

|

3 3 3 |

2 |

2 |

|

9 |

|

|

|

CC |

|

|

|

8 |

|

DD |

|

|

|

|

|

5 5 3 3 3 3 3 2 |

|

99 9 9 AA AA |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||

|

|

|

|

5 3 |

2 |

|

|

A A A |

A |

8 |

|

|

8 |

8 |

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

5 |

3 3 |

|

|

|

A AA A |

|

|

|

8 |

|

8 |

8 |

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

5 |

|

|

2 |

|

|

|

A A A |

|

88 8 |

8 8 8A 8 88 |

|

|

|

|

|||||

|

|

|

|

55 |

2 |

|

|

|

|

A |

8 |

|

|

8 |

8 |

8 |

C |

|

|

7 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

2 |

|

|

|

|

A |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

6 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

7 |

7 |

7 |

1 |

|

|

|

|

1 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

7 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

1 |

1 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

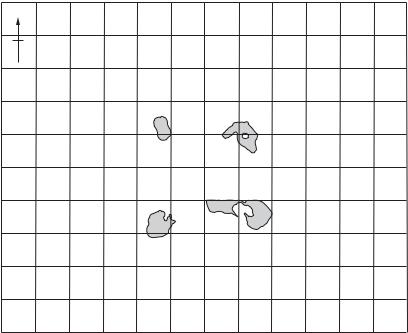

Figure 32 Mask site Spatial distribution of all item points over the Mask site, identified by cluster assignment in the 13-cluster solution (the shaded areas are hearths). Source: R. Whallon: ‘Unconstrained clustering for the analysis of spatial distributions in archaeology’, Intrasite spatial analysis in archaeology, ed. H. Hietala (Cambridge University Press, 1984), fig. 15.