A Dictionary of Archaeology

.pdfto watch for game and plan hunting strategies. Binford studied the activities that took place, such as watching for game, eating and talking, crafts, target shooting, how much time was spent on each, and the related discard or placement of items that took place.

Robert Whallon (1984) used Binford’s study of the Mask site as the basis for the first application his

technique of UNCONSTRAINED CLUSTERING. The

data consisted of the exact locations of objects of five types across the site: large bones, bone scraps, wood scraps, tools and projectiles, as well as the positions of hearths and large stones. The first step in the analysis was to smooth the spatial distribution of each type to give a smooth contoured surface the height of which represented the density of objects of

that type (see TREND SURFACE ANALYSIS). At each

point where an object was located, the height of each surface was calculated and expressed as a percentage of the total of all the heights at that location.

A data matrix consisting of the percentages of all the types at all the locations, measured in this way, was subjected to CLUSTER ANALYSIS. The ‘best’ number of clusters was not clear, so both the 7-- cluster and the 13-cluster solutions were plotted (see Fig. 32). Some of the clusters defined in this way formed single contiguous groups of locations, while others formed small numbers of such groups. Finally, Whallon interpreted these clusters in terms of activities that had taken place on the site, such as eating, wood-carving, target practice.

Despite being acclaimed as a major advance in SPATIAL ANALYSIS, Whallon’s approach seems to have serious defects. It seems to complicate rather than simplify or elucidate: from five object types, some with very simple distribution patterns, it derived either 7 or 13 clusters, most of which had two or more sub-clusters. Several spurious clusters were caused by the smoothing technique spreading the density of object types well beyond the area that they actually occupy. Thus a cluster described as comprising 25% of a particular type may have had none of that type within its borders. The root cause seems to be a mismatch between the attempt to define edges of areas, with the use of smoothing techniques which blur any such distinctions. It seems unlikely that this technique would perform well on a real archaeological site of any complexity.

L.R. Binford: ‘Dimensional analysis of behaviour and site structure: learning from an Eskimo hunting stand’ AA 43 (1978), 330–61; R. Whallon: ‘Unconstrained clustering for the analysis of spatial distributions in archaeology’,

Intrasite spatial analysis in archaeology, ed. H. Hietala (Cambridge, 1984), 242–77; H.P. Blankholm: Intrasite

MATENKUPKUM 385

spatial analysis in theory and practice (Aarhus, 1991), 75–90.

CO

mastaba-tomb (Arabic: mastaba, ‘bench’) Type of Egyptian tomb with a rectangular block-shaped superstructure, used from the 1st dynasty (c.3000 BC) until the end of the Old Kingdom (c.2150 BC) primarily in the vicinity of Cairo and the Faiyum. The most basic form of mastaba consisted of a subterranean burial chamber surmounted by a rectangular superstructure made of mud-bricks or stone masonry, usually incorporating offering niches or chapels.

A.J. Spencer: Death in ancient Egypt (Harmondsworth, 1982), 45–111; N. Cherpion: Mastabas et hypogées d’Ancien Empire: le problème de la datation (Brussels, 1989).

IS

Matara Settlement site of the pre-Axumite and Axumite periods, located in the Ethiopian highlands. The earliest occupation levels (dated to c.500–300 BC) include artefacts showing considerable South Arabian influence (as at YEHA); the stratigraphy of this phase has also helped to corroborate the pre-Axumite ceramic sequence, which was previously based primarily on typologies and seriation. By the 8th century AD Matara had acquired a new importance as an Axumite town, perhaps as a result of its geographical position roughly midway between AXUM and ADULIS. The prosperity of the town at this time has been demonstrated by the discovery of a hoard of Roman and Byzantine goldwork, as well as the excavation of several large, multi-room houses similar to those of the elite at Axum.

F. Anfray: ‘Matara’, AE 7 (1967), 33–88.

IS

Matenkupkum Limestone cave on New Ireland, Papua New Guinea (see OCEANIA 2), inhabited between 35,000 and 10,000 years ago. It demonstrates that humans had settled the western Pacific islands by the late Pleistocene, and it is the earliest evidence of island occupation in the world outside southeast Asia. There were low levels of occupation until around 20,000 years ago, with a limited range of animals and stone tools derived from the local rivers; after that date, there is evidence of the introduction of animals, obsidian from New Britain, and structural evidence such as hearths.

J. Allen et al.: ‘Human Pleistocene adaptations in the tropical island Pacific: recent evidence from New Ireland,

386 MATENKUPKUM

a Greater Australian outlier’, Antiquity 63 (1989), 548–61; C. Gosden and N. Robertson: ‘Models for Matenkupkum: interpreting a late Pleistocene site from southern New Ireland, Papua New Guinea’, Report of the Lapita Homeland Project, ed. J. Allen and C. Gosden (Canberra, 1991), 20–45.

CG

material culture studies see ACTUALISM;

CONTEXTUAL ARCHAEOLOGY;

ETHNOARCHAEOLOGY; FORMAL ANALYSIS

Matola Early Iron Age site on the outskirts of Maputo, Mozambique, dated to the 2nd–5th centuries AD. This single-component site was the subject of excavations in 1975 and 1982. No structural features have been found, and little in the way of organic remains. The chief interest of the site lies in its early date, and the clear affinities of the pottery with ceramics of the Early Iron Age (KWALE ware) in the coastal hinterland of Kenya, dated to the 2nd and 3rd centuries AD: a key element in the argument for a coastwise spread of early farming communities from the north.

T. Cruz e Silva: ‘First indications of Early Iron Age in southern Mozambique: Matola IV 1/68’, Proceedings of the 8th Panafrican Congress of Prehistory and Quaternary Studies Nairobi, 5 to 10 September 1977, ed. R.E. Leakey and B.A. Ogot (Nairobi, 1980); J. Morais: The early farming communities of southern Mozambique, Studies in African Archaeology 3 (Stockholm 1988).

RI

Matupi Later Stone Age (LSA) cave in the Ituri Forest, Zaïre, excavated in 1974. The site is important for its indication that LSA microlithic industries were present from 30,000 uncal BP and possibly much earlier. Also, there is evidence that during the late Paleistocene, at least from the Last Glacial Maximum and through most of the Holocene, the site was in savannah country, with the forest margin an estimated 10 km to the west. The encroachment of the forest is thus a very recent phenomenon. The earliest industries contain few shaped tools; later assemblages contain more retouched pieces, but few geometrics. Reamers and a bored stone are present at levels dating to 20,000 uncal BP.

F. Van Noten: ‘Excavations at Matupi Cave’, Antiquity 51 (1977), 35–40.

RI

Mauryan period First unified state of the Indian subcontinent as a whole. The Mauryan

empire (c.324–184 BC) extended from its core region of Magadha in the Ganges Valley to cover most of South Asia. Prominent rulers include Chandragupta (324–301 BC) and Asoka (273–232 BC). Most knowledge of the Mauryan period derives from such historical sources as the reports of the Seleucid ambassador (c.302 BC) and the Arthashastra, a political exegesis on the nature of kingship attributed to Kautilya, a Mauryan government official (324–301 BC), the preserved text of which was probably written down at some unknown time after the Mauryan period itself. Wooden architecture was prevalent at the Mauryan capital of Pataliputra (modern Patna), leaving little archaeological trace.

See also KAUSAMBI and TAXILA.

R. Thapar: Asoka and the decline of the Mauryas (Oxford, 1961); V.A. Smith: The Oxford history of India, 4th edn (Delhi, 1981), 94–163.

CS

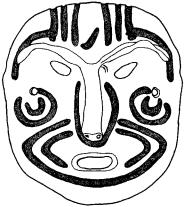

Mawaki Early to Final Jomon site in Ishikawa prefecture, Japan (5000–300 BC; see JAPAN 2 for discussion of Jomon period). Fish remains suggest year-round occupation. The bones from hundreds of dolphins were recovered form the Early–Middle Jomon layers suggesting large-scale communal exploitation. A Late Jomon clay mask and rebuilt circular arrangements of large wooden posts from the Final Jomon point to increased ritual activity in the later phases of the site.

T. Hiraguchi: ‘Catching dolphins at the Mawaki site, central Japan, and its contribution to Jomon society’,

Figure 33 Mawaki Late Jomon clay mask from the Mawaki site, Ishikawa prefecture, Japan (h. 128 mm).

Source: K. Suzuki (ed.): Jomonjin no seikatsu to bunka. Kodaishi Fukugen (Tokyo: Kodansha, 1988), fig. 222.

Pacific Northeast Asia in prehistory, ed. C.M. Aikens and S.N. Rhee (Pullman, 1992), 35–46.

SK

Ma-wang-tui (Mawangdui) Earthen mound, 16 m in height, located 4 km from Ch’ang-sha city, in the province of Hu-nan, China. The central part was excavated early in 1972 and revealed a tomb of the Han period (206 BC–AD 220). This tomb (M1) is remarkable for the excellent preservation of the body and internal organs of the occupant, a 50-year- old female of short stature. Details from the autopsy of the cadaver showed a variety of ills leading up to her death, including coronary arteriosclerosis, pulmonary tuberculosis and gall-stones. Another tomb (M3), excavated in 1973 and precisely dated to 168 BC, is especially noted for the preservation of a large quantity of writings on silk, amounting to well over 10,000 characters. There are some 20 varieties of writings (several illustrated) dealing with such subjects as contemporary philosophical themes, early historical events, military information, astronomical and calendrical matters, geography and medicine.

Anon.: Ch’ang-sha Ma-wang-tui yi-hao Han-mu [The Han period tomb No. 1, Ma-wang-tui, Ch’ang-sha] (Peking, 1973); ––––: Ch’ang-sha Ma-wang-tui yi-hao Han-mu kushih yen-chiu [Examination of the ancient cadaver from Tomb No. 1 Ma-wang-tui, Ch’ang-sha] (Peking, 1980);

––––: Ma-wang-tui Han-mu po-shu [Silk manuscripts from the Han tomb at Ma-wang-tui], vols 1/3/4 (Peking, 1980–85); Ho Chien-chün and Chang Wei-min: Ma- wang-tui Han-mu [The Han period tomb of Ma-wang-tui] (Peking, 1982).

NB

Maya see LOWLAND MAYA

Mayapán Small walled settlement in the northern LOWLAND MAYA area of Mexico. Mayapán, incorporating an area of 4 sq. km, with a population of approximately 12,000 people, was the centre of a confederacy of 16 states during the Late Postclassic period. Headed by the Cocom family, this confederacy broke down, however, and after a revolt against the Cocoms sometime around AD 1450 the city was burned and its inhabitants fled. The site’s main ceremonial complex, said to be a smaller and poorly constructed copy of CHICHÉN ITZÁ, is known for distinctive temple structures and human-figure INCENSARIOS. Structures and ceramics similar to those of the Mayapán are found at Late Postclassic sites throughout the Maya lowlands.

H.E.D. Pollock, R.L. Roys, T. Proskouriakoff and A.L.

MEADOWCROFT ROCKSHELTER 387

Figure 34 Maya Intricate Maya carving on the side of Stele 31, Tikal, Guatemala. Source: W. Coe, Tikal Project, University Museum, University of Pennsylvania, Philadephia.

Smith: Mayapan, Yucatan, Mexico (Washington, D.C., 1962).

PRI

Maysar see ARABIA, PRE-ISLAMIC

Meadowcroft Rockshelter Deeply stratified rockshelter in southwestern Pennsylvania which has yielded some of the earliest evidence of human occupation in eastern North America. A series of more than fifty radiocarbon dates indicates that human occupation of the site extended from c.12,500 BC to AD 1000. Flaked stone artefacts

388 MEADOWCROFT ROCKSHELTER

associated with the earlier occupation zones include an unfluted, lanceolate projectile point, prismatic blades, retouched unifacial (Mungai) knives and gravers. Despite the early dates, all of the faunal material associated with the early components is essentially modern. Some archaeologists have challenged the early dates because of the possibility of contamination from coal. Meadowcroft has also yielded information about the ways in which subsequent Archaic, WOODLAND and Late Prehistoric peoples adapted to changing Holocene environmental conditions.

J. Adovasio and R. Carlisle: ‘Pennsylvania pioneers’. Natural History 95 (1986), 20–7; J. Adovasio, J. Donahue and R. Stuckenrath: ‘The Meadowcroft Rockshelter radiocarbon chronology: 1975–1990’, AA 55 (1990), 348–54; K. Tankersley and C. Munson; ‘Comments on the Meadowcroft Rockshelter radiocarbon chronology and the recognition of coal contaminants’, AA 57 (1992), 321–6.

RJE

mean (arithmetic) Statistical term used to describe one of many ‘measures of central tendency’ of a VARIABLE, indicating a ‘typical’ value. It is the sum of the values of the variables, divided by the number of values, often referred to as the ‘average’. For instance, the mean length of 20 flint flakes would be the sum of their lengths divided by 20.

J.E. Doran and R.F. Hodson: Mathematics and computers in archaeology (Edinburgh, 1975), 38; S. Shennan: Quantifying archaeology (Edinburgh, 1988, 35–8; M. Fletcher and G.R. Lock: Digging numbers (Oxford, 1991), 34–8.

CO

Mecca see ISLAMIC ARCHAEOLOGY

Mechta-Afalou Population type or ‘race’, defined by Marcellin Boule and Henri V. Vallois in 1934, on the basis of skeletal material from two sites in eastern Algeria: Mechta el-Arbi, excavated by Gustave Mercier and Albert Debruge in 1907–23, and Afalou bou Rhummel, excavated by Camille Arambourg in 1928–30. The first site is a CAPSIAN ‘escargotière’ and the second an IBEROMAURUSIAN rock shelter, hence the type was from the beginning associated with at least two different ‘EPIPALAEOLITHIC’ industries in the Maghreb.

Classically, the Mechta-Afalou population, which is regarded as ‘Cromagnoid’, is said to be characterized by considerable robustness of form, with marked sexual dimorphism. The average height was 1.72–1.74 m for men and 1.62–1.64 m

for women. The cranium was usually elongated with a protruding glabella and the face short and broad with low rectangular orbits and a wide interorbital region. The mandible was massive with a short vertical ramus and gonial eversion. Evulsion of the upper incisors, and sometimes the lower ones as well, was a common cultural practice among the members of this group.

According to Marie-Claude Chamla, a ‘gracilization’ process can be observed among the 114 ‘Mechtoids’ found in the cemetery of Columnata, but nonetheless the type persisted in the Maghreb through the Capsian and Neolithic periods until Protohistoric times, when it was finally overwhelmed by an incoming ‘Proto-Mediterranean’ population. The type is sufficiently well characterized to have been recognised in areas far from the Maghreb, particularly at Wadi Halfa and Jebel Sahaba in the Nile valley and at Hassi el Abiod in the TAOUDENNI BASIN, in various archaeological contexts. Lubell et al. (1984) take objection to the typological approach employed in earlier studies.

Their MULTIVARIATE ANALYSIS of 6 cranial and

facial measurements on 68 individuals from 4 groups in the Maghreb (Iberomaurusian, Columnatian, Capsian and Neolithic) showed in their view that these populations constituted ‘an almost indistinguishable mass’, and they used this as an argument in favour of population continuity in the area and against any ‘Proto-Mediterranean’ incursion. Nevertheless, they were obliged to concede that Iberomaurusian males did still form ‘a distinct, relatively homogeneous and identifiable group’. With regard to the origins of the MechtaAfalou population, an apparent contradiction has been found to exist between the palaeontological and the archaeological data. There is a technological and typological contrast, and a chronological hiatus, between the Iberomaurusian and the preceding ATERIAN industrial complex; yet, as Denise Ferembach (1986) has shown, the specimens associated with the Aterian at DAR ES-SOLTANE II and other Moroccan sites can well be regarded as ancestral to those of Mechta-Afalou type. She proposes to bridge the gap by postulating a hypothetical migration of the Aterian people to Europe and their return in the guise of Iberomaurusian culture, a ‘tragic adventure’ which Gabriel Camps rejects as ‘incredible.’ Olivier Dutour, on the other hand, points out that anatomically modern populations did exist at this time in the Nile valley, at WADI KUBBANIYA and Nazlet Khater 4 (the latter dated to 33,470 ± 360 BP), and that this is relevant when considering the origins of the ‘Cromagnoids’ in North Africa as a whole.

G. Camps: Les civilizations préhistoriques de l’Afrique du Nord et du Sahara (Paris, 1974); K.P. Oakley, B.G. Campbell and T.I. Molleson: Catalogue of fossil hominids, Part 1: Africa, 2nd edn (London, 1977); M.C. Chamla: ‘Le peuplement de l’Afrique du Nord de l’épipaléolithique à l’époque actuelle’, L’Anthropologie 82 (1978), 385–430; D. Lubell, P. Sheppard and M. Jackes: ‘Continuity in the Epipaleolithic of Northern Africa with emphasis on the Maghreb’, AWA 3 (1984), 143–91; P.M. Vermeersch, E. Paulissen, G. Gijselings, M. Otte, A. Thoma, P. van Peer and R. Lauwers: ‘33,000 yr old chert mining site and related Homo in the Egyptian Nile Valley’, Nature 309 (1984), 342–4; D. Ferembach: ‘Les hommes du paléolithique supérieur autour du Bassin Méditerranéen’, L’Anthropologie 90 (1986), 579–87; G. Camps: ‘Un Scénario de “préhistoire catastrophe”, l’odysée des Atériens et le retour des Ibéromaurusiens’,

Bulletin de la Société Préhistorique Française 84/3 (1987), 67–8; O. Dutour: ‘Les Cro-Magnons sont-ils originaires de Nord de l’Afrique?’, DA 161 (1991) 68–73.

PA-J

Medes Indo-Iranian people who are first mentioned in cuneiform texts in the early 1st millennium BC, although they probably settled in northern and western Iran as early as the 14th century BC. Possible early Median sites are Tell Gubba, in the Hamrin Basin, and Tille Höyük in southern Anatolia. The Medes were at first dominated by the late ASSYRIAN rulers of the 9th–8th centuries BC, but by c.700 BC – benefitting from the political vacuum left by the collapse of ELAM – they had begun to create their own empire, covering large areas of Iran, northern Mesoptamia and eastern and central Asia Minor (where they inherited much of the kingdom of URARTU). Between 614 and 612 BC they conquered the Assyrian cities of Assur, Nineveh and Kalhu, although it was their allies the Babylonians who eventually inherited the principal Assyrian territories. The capital of Media was the western Iranian city of Ecbatana (modern Hamadan), which later became an important PERSIAN city under the Achaemenid dynasty. In the mid-6th century BC Cyrus the Great defeated the Medes, thus effectively absorbing Media into the empire of the Persians, their former vassals.

The material culture of the Medes is still relatively undocumented, and few Median textual records have survived; although their palace at Ecbatana has not yet been excavated, the fortified sites of Godin Tepe and Tepe Nush-i Jan, both situated close to Ecbatana, were investigated during the 1960s and 1970s. The Central Temple at Tepe Nush-i Jan appears to have incorporated a FIRE ALTAR dating to the 8th century BC, while the excavations of the main fortress revealed a cache of

MEGALITHIC 389

321 silver items buried in a bronze vessel in c.600 BC.

W. Culican: The Medes and Persians (London and New York, 1965); D. Stronach: ‘Tepe Nush-i Jan, a mound in Media’, BMMA 27 (1968); J. Curtis: Nush-i Jan III: The small finds (London, 1984).

IS

median Statistical term referring to the ‘middle’ one of a set of values of a VARIABLE, or the midpoint of the middle two if there is an even number of them. Thus the median diameter of three pots, the diameters of which are 15 cm, 20 cm and 40 cm, would be 20 cm, whereas the MEAN diameter would be 25 cm. Sometimes this value is used as an alternative to the mean, especially in NON-PARAMETRIC

STATISTICS.

J.E. Doran and F.R. Hodson: Mathematics and computers in archaeology (Edinburgh, 1975), 39; S. Shennan: Quantifying archaeology (Edinburgh, 1988), 38–40; M. Fletcher and G.R. Lock: Digging numbers (Oxford, 1991), 33–4.

CO

medieval archaeology see EUROPE,

MEDIEVAL AND POST-MEDIEVAL 1

Medina see ISLAMIC ARCHAEOLOGY

Medinet Habu (anc. Djamet; Jeme) Egyptian temple complex of the New Kingdom (c.1550–1070 BC) at the southern end of the Theban west bank, opposite modern Luxor. Most of the archaeological and epigraphic work at the site was undertaken by the Chicago Epigraphic Survey in the 1920s and 1930s. The earliest section of the complex was a small temple built by Hatshepsut and Thutmose III in the early 15th century BC, but this was eclipsed about 300 years later by the construction of the mortuary temple of Ramesses III (c.1198–1166 BC). Murnane (1980) discusses the significance of New Kingdom mortuary temples. See also RAMESSEUM

(on which the basic plan of Ramesses III’s mortuary temple was modelled).

Epigraphic Survey, Chicago: Medinet Habu, 8 vols (Chicago, 1930–70); U. Hîlscher: The excavation of Medinet Habu, 5 vols (Chicago, 1934–54); W.J. Murnane:

United with eternity: a concise guide to the monuments of Medinet Habu (Chicago and Cairo, 1980).

IS

megalithic From the early Neolithic onwards, megalithic (literally, ‘large stone’) architecture formed one of the most distinctive and enduring

390 MEGALITHIC

features of prehistoric European architecture. The term megalithic is applied to any prehistoric monument or building that makes use of very large, unshaped blocks of stone as a principal component

– although earth, rubble, drystone and timber often form subsidiary materials. By contrast, when blocks are carefully shaped and fitted – in Mycenaean architecture, for example – the term CYCLOPEAN is preferred. (STONEHENGE and the MALTESE TEMPLES, built of carefully shaped stones but conventionally regarded as prime examples of megalithic design, are among the exceptions that prove this rule.)

There are two key expressions of megalithic building: tomb-building in the Neolithic (discussed in this article), and the erection of ceremonial monuments in the Neolithic and the Bronze Age (see STONE CIRCLES). Megalithic tombs are known throughout much of northwestern and western Europe, particularly along the Atlantic seaboard. They are commonly grouped into key architectural forms such as PASSAGE

GRAVES, GALLERY GRAVES and ALLÉES

COUVERTES, with many regional variants such as the BOYNE VALLEY passage graves and SEVERNCOTSWOLD gallery graves (Joussaume 1988 provides a regional survey). Until the advent of radiocarbon dating, there were many attempts to trace the evolution of these regional styles through an inter-linked evolutionary tree, sometimes taken to begin in Iberia, Egypt or the Near East (see also DIFFUSIONISM). However, during the 1960s radiocarbon dates led archaeologists such as Colin Renfrew to suggest that the Breton tombs were among the earliest examples: the chronological sequences suggested by the diffusionary schemes thus became untenable, and it was suggested that megalithic construction might have been invented independently in several regions. The emphasis shifted to trying to understand why groups building megalithic structures were receptive to the idea of monumental architecture, rather than the construction of elaborate stylistic family trees.

Such explanations have stressed the collective and (supposedly) egalitarian nature of many of the burials; the monumental effect of the building within the natural landscape; and the ‘legitimizing’ symbolism of maintaining contact with dead ancestors. This suggests to many researchers that megalithic tombs were linked to concerns about establishing rights over agricultural land, and the reinforcement of social cohesion – perhaps in answer to pressure from neighbouring groups. Other analyses have thrown doubt on the egalitarian nature of burial in megalithic tombs (e.g. Bradley

1984), suggesting that some more elaborate tombs reveal signs of internal social competition. Various studies have also tried to link megalithic monuments to territories and to calculate local populations (notably Renfrew 1976).

Another long-running theme within megalithic studies has been the attempt to identify ALIGNMENTS in the orientation of the covering barrows and architectural elements of the tombs. The roofbox of NEWGRANGE is the most dramatic example of this, apparently aligned to allow winter sun to fill the chamber around the time of the winter solstice. More recently, studies (e.g. Hodder, 1992) have attempted to reveal the symbolism of Neolithic tombs as ‘houses for the dead’, while there have been renewed attempts to understand the ritual breaking of pottery, feasting and other activities that seem often to have taken place in the tomb forecourt. There have been suggestions, too, that the symbols and curvilinear designs of megalithic art found most notably on Breton and Irish passage tombs (surveyed by Shee Twohig, 1981) may be related to SHAMANISTIC practices (LewisWilliams, 1993).

C. Renfrew: ‘Megaliths, territories and populations’,

Acculturation and continuity in Atlantic Europe, ed. S. De Laet (Bruges, 1976), 198–220; C. Renfrew, ed.: The megalithic monuments of western Europe (London, 1981); E. Shee Twohig: The megalithic art of Western Europe (1981); R. Bradley: The social foundations of prehistoric Britain

(London, 1984); R. Joussaume: Dolmens for the dead; megalith building throughout the world (London, 1988); I. Hodder: ‘Burials, houses, women and men in the European Neolithic’, Theory and practice in archaeology, ed. I. Hodder (London, 1992), 45–83; J.D. LewisWilliams and T.A. Dawson: ‘On vision and power in the Neolithic: evidence from the decorated monuments’, CA 34 (1993), 55–65.

RJA

megalithic yard Since at least the time of the antiquary William Stukeley in the mid-18th century, researchers into the megalithic stone circles of the British Isles have suggested that the structures were laid out using a standard unit of measurement. The strongest exponent of the idea in recent years was Professor Alexander Thom, who in 1955 analysed the diameters of 46 megalithic rings and found that they tended to be set at multiples of about 1.657 m. Heggie (1981) summarizes the evidence, concluding that there is a case for a regular unit of measurement, but that it need not have been as precise or as standardized as Thom has claimed.

A. Thom: ‘A statistical examination of the megalithic sites in Britain’, J.R. Stat. Soc, A118 (1955), 275–95; A. and

A.S. Thom: ‘The megalithic yard’, Measurement and control 10 (1977), 488–92; D. Heggie: Megalithic science (London, 1981), 32–60.

RJA

megaron Distinctive architectural form employed in the Aegean Bronze Age, and typically consisting of a large hall with a central hearth, one or more anterooms, and a porch. The most famous examples form key elements of the great MYCENAEAN palaces such as PYLOS, built in the second half of the 2nd millennium BC.

RJA

Megiddo (Tell el-Mutesellim) CANAANITE – and later ISRAELITE – settlement in the southern Jezreel valley of Israel, about 35 km southeast of Haifa. Megiddo was the setting for the Egyptian king Thutmose III’s victory over MITANNI in c.1503 BC, and it was subsequently transformed into an Egyptian garrison during the 15th and 14th centuries BC. Tell el-Mutesellim was identified with Megiddo when it was first excavated by J. Schumacher in 1903–5. The subsequent excavations of Clarence Fisher and Yigael Yadin revealed approximately twenty-five major phases of occupation from the Chalcolithic period (c.3300 BC) to the Persian domination (c.4th century AD).

C.S. Fisher: Excavations of Armageddon (Chicago, 1929); C. Watzinger: Tell el-Mutesellim II (Leipzig, 1929); R.S. Lamon and G.M. Shipton: Megiddo I (Chicago, 1939); G. Loud: The Megiddo ivories (Chicago, 1939); ––––: Megiddo II (Chicago, 1948); G.I. Davies: Megiddo (Cambridge, 1986).

IS

Mehi see KULLI COMPLEX

Mehrgarh Early agricultural settlement dating back to the 7th millennium BC, located in the Kacchi plain in western Pakistan. The site of Mehrgarh, comprising a series of mounds spread along the banks of the Bolan River, was excavated from 1974 to 1986 by Jean-François Jarrige. The stratigraphy at Mehrgarh has been divided into seven periods, of which the earliest three belong to the Neolithic period, when agriculture was first developing in South Asia.

B. and R. Allchin: The rise of civilization in India and Pakistan (Cambridge, 1982), 105–8; J.-F. Jarrige: ‘Chronology of the earlier periods of the greater Indus as seen from Mehrgarh, Pakistan’, South Asian archaeology, 1981, ed. B. Allchin (Cambridge, 1984), 21–8.

CS

MELKA-KUNTURE 391

Meidum Egyptian funerary site, located at the entrance to the Faiyum basin, where one of the earliest pyramid complexes was constructed. The stone-built pyramid at Meidum is thought to have been built by Sneferu (c.2575–2551 BC) for the burial of his father Huni. Since Sneferu also constructed two pyramids for himself at DAHSHUR, in the southern part of the Memphite necropolis, he is generally regarded as the first Egyptian ruler to experiment with the engineering techniques necessary to accomplish the transition from the ‘step-pyramids’ of the 3rd-dynasty rulers (see SAQQARA) to the ‘true pyramids’ of the 4th dynasty at GIZA. The Meidum pyramid is surrounded by the rubble of its outer masonry, evidently indicating a dramatic collapse perhaps resulting from unsatisfactory methods of construction – opinions differ, however, as to whether the collapse took place before the completion of the monument (Mendelsson 1973) or as late as the 14th century BC (Edwards 1974). The pyramid is surrounded by a number of MASTABA-TOMBS of similar date, including those of Nefermaat and Ity, which contained surviving decoration in the form of inlaid pigments and paintings depicting scenes of daily life (including the famous ‘Meidum geese’).

W.M.F. Petrie: Meydum (London, 1892); ––––, E. Mackay and G.A. Wainwright: Meydum and Memphis III (London, 1910); K. Mendelsson: ‘A building disaster at the Meidum pyramid’, JEA 59 (1973), 60–71; I.E.S. Edwards: ‘The collapse of the Meidum pyramid’, JEA 60 (1974), 251–2.

IS

Meir Group of decorated rock-cut tombs in Middle Egypt (about 50 km northwest of modern Asyut) dating to the 6th and 12th dynasties (c.2323–2150 and 1991–1783 BC respectively). The tombs, badly pillaged during the 19th century, were excavated and recorded by Aylward Blackman over the course of several seasons between 1912 and 1950. They contained the funerary remains of the governors of Cusae, as well as members of their families. There are few remaining traces of the town of Cusae itself, about 7 km to the east, which was the capital of the 14th province of Upper Egypt.

A.M. Blackman: The rock tombs of Meir, 6 vols (London, 1914–53).

IS

Melanesia see OCEANIA 2

Melka-Kunture Site in Ethiopia where very deep ACHEULEAN/OLDOWAN stratigraphy

392 MELKA-KUNTURE

(stretching back to over 1.5 million years ago) was excavated. Finds have included lithics as well as the remains of hominids, but the excavations themselves have not yet been fully published.

F. Hours: ‘Le Middle Stone Age de Melka-Kunturé: résultats acquis en 1971’, Documents pour Servir à l’Histoire des Civilizations Ethiopiennes 4 (1973), 19–29; J. Chavaillon: ‘Mission archéologique Franco-Ethiopienne de Melka-Kontouré’, L’Ethiopie avant l’Histoire 1 (1976), 1–22.

IS

Melos see PHYLAKOPI

Meluhha Akkadian word referring to an unidentified geographical zone that is frequently mentioned in cuneiform texts from SUMER. Along with Magan (see UMM ANN-NAR), it was part of an extensive trading network centred on the Persian Gulf during the Akkadian and Ur III periods (c.2317–2000 BC) (see Tosi 1984). A seal from the Akkadian period apparently bears a depiction showing a Meluhhan acting as interpreter on behalf of a group of foreigners (Lamberg-Karlovsky 1981). In the 2nd and 3rd millennia BC the term probably refers to the INDUS CIVILIZATION, but by the 1st millennium BC it may have designated NUBIA.

C.C. Lamberg-Karlovsky: ‘Afterword’, Bronze Age civilization of Central Asia, ed. P. Kohl (New York, 1981), 386–7; M. Roaf: ‘Weights on the Dilmun standard’, Iraq 44 (1982), 137–42; M. Tosi: ‘Early maritime cultures of the Arabian Gulf and the Indian Ocean’, Bahrain through the ages, ed. Shaikha Haya al Khalifa and M. Rice (London, 1984), 94–107; K. Kitchen: Documentation for ancient Arabia I (Liverpool, 1994), 153–62.

IS

Memphis (anc. Mn-nfr) Located only 30 km from the head of the Egyptian Delta, the ancient city of Memphis occupied a crucial geographical position at the junction between Upper and Lower Egypt. It was the principal city of Egypt from c.3000 BC to the Arab conquest of AD 641, and the Memphite necropolis extended from ABU ROASH in the north, through SAQQARA to DAHSHUR in the south. The remains of the city of Memphis have suffered greatly from the proximity of the suburbs of modern Cairo, but archaeologists from the early 1800s to the present day have gradually pieced together parts of the network of temples, palaces and private houses, including the palaces of Merenptah (1213–1203 BC) and Apries (589–570 BC), and a large temple complex dedicated to the local god Ptah. Most of the recorded buildings tend

to date from the New Kingdom onwards, although a survey of the entire site undertaken by the Egypt Exploration Society in the 1980’s (Jeffreys 1985) has begun to reveal aspects of the earlier phases of the city.

W.M.F. Petrie: Memphis I (London, 1909); R. Anthes: Mitrahina 1956 (Philadelphia, 1965); D.G. Jeffreys: The survey of Memphis (London, 1985); –––– and A. Tavares: ‘The historic landscape of Early Dynastic Memphis’, MDAIK 50 (1994), 143–74.

IS

Mendes (anc. Per-banebdjedet) Egyptian settlement site consisting of two mounds (Tell el-Rub’a and Tell Timai) in the central Nile Delta, about 95 km north of Cairo. At the northwestern edge of Tell el-Rub’a is a cemetery of rams sacred to the local ram-god Banebdjedet. The site was already occupied in the late predynastic period and by the 26th dynasty it had developed into one of the principal Lower Egyptian cities.

H. De Meulenaere and P. Mackay: Mends II (Warminster, 1976); D.J. Brewer and R.J. Wenke: ‘Transitional late pre- dynastic-Early Dynastic occupations at Mendes: a preliminary report’, The Nile Delta in transition: 4th–3rd millennium BC, ed. E.C.M. van den Brink (Tel Aviv, 1992), 191–7.

IS

Merimda Beni Salama Egyptian prehistoric site (c.4880 to 4200 BC), about 25 km northwest of Cairo, which is the earliest surviving predynastic village in Lower Egypt, preceded only by the less substantial FAIYUM A encampments along the northern shores of Lake Qarun. It is the typesite of the Merimda phase of the Lower Egyptian predynastic (Neolithic) sequence, roughly corresponding to the late BADARIAN and AMRATIAN periods in Upper Egypt. The principal features of the Merimda assemblage were decorated pottery, pear-shaped stone maceheads, chipped stone axes, saw-edged sickle-blades, spindlewhorls, bone harpoons, fish-hooks and diorite vases. It used to be suggested that the contrast with the microlithic technology of the preceding EPIPALAEOLITHIC period was so great that the Merimda population must have been an intrusive non-Egyptian group. However, earlier Egyptian sites in the eastern Sahara, such as NABTA PLAYA, show strong evidence of continuous cultural development from the Epipaleolithic toolkit to that of the Neolithic.

H. Junker: Vorläufer Bericht über die Grabung der Akademie der Wissenschaften in Wien auf der neolitischen Siedlung von Merimde-Beni Salâme, 6 vols (Vienna, 1929–40); B.J. Kemp: ‘Merimda and the theory of house burial in pre-

historic Egypt’, CdE 43 (1968), 22–33; M.A. Hoffman: Egypt after the pharaohs (New York, 1979), 167–81; J. Eiwanger: Merimde-Benisalâme, 2 vols (Mainz, 1984–8).

IS

Meroe, Meroitic Town in the Butana region of Sudan, excavated by John Garstang (1911), George Reisner (Dunham and Chapman 1952–63) and Peter Shinnie (1967), which became the centre of the Kushite kingdom in the Meroitic period (c.300 BC–AD 350). Near the town is the site of Begarawiya, a cemetery of small pyramidal royal tombs of the Meroitic period, the earliest of which were located in the south. The settlement includes a number of two-storeyed palaces, a temple of Isis dating to the Napatan period (c.1000–300 BC) and a temple of Amun which was established in the 7th century BC and elaborated in the 1st century AD. To the east of the town there was also a temple of Apedemak, the Nubian lion-god, dating to the 3rd century BC. The presence of large slag heaps once led to the suggestion that iron-smelting was an important part of the city’s economy, which perhaps involved the supply of iron to the rest of Africa. More recently, however, it has been pointed out that the quantities of iron artefacts found either in the settlement or in the cemetery are by no means unusually high – it is therefore likely that iron did not become an important economic factor until the post-Meroitic period.

The Meroitic period was roughly contemporary with the Ptolemaic and Roman periods in Egypt. The archaeological traces of commerce with GrecoRoman Egypt have survived both in the form of a cache of ebony and ivory, excavated at the trading centre of Wad Ban Naga, and the numerous imported grave goods which are found alongside the distinctive Meroitic pottery and metalwork at sites

such as FARAS, GEBEL ADDA and KARANOG.

The material culture and political structure of the Meroitic period do not seem to have differed greatly from their NAPATAN counterparts, the main indication of the transferral of power from Napata to MEROE being the appearance of royal cemeteries at Begarawiya near Meroe in the early 3rd century BC. This was the first truly literate phase of indigenous Nubian culture. There were two forms of script used to write the Meroitic language; one comprised 23 signs derived from the Egyptian hieroglyphic system and the other was a more cursive script similar to DEMOTIC. Although Francis Griffith succeeded in deciphering the script in 1909, the lack of any surviving languages derived from the ancient Meroitic tongue has hindered most attempts at

MERSIN 393

actually translating the surviving texts.

J. Garstang et al.: Meroe: city of the Ethiopians (Oxford, 1911); D. Dunham and S. Chapman: The royal cemeteries of Kush, III–V (Boston, 1952–63); P.L. Shinnie: Meroe: a civilization of the Sudan (London, 1967); –––– and F.J. Kense: ‘Meroitic iron working’, Meroitic Studies, ed. N.B. Millet and A.L. Kelley (Berlin, 1982), 17–28; L. Török:

Meroe city: an ancient African capital (London, 1997); D. Wildung, ed.: Sudan: ancient kingdoms of the Nile (Paris, 1997), 204–417.

IS

Mersa Matruh (anc. Paraetonium) Site of a lagoon and harbour on the Egyptian Mediterranean coast, about 200 km west of Alexandria, which was the Ptolemaic city of Paraetonium. A small settlement of the Late Bronze Age (c.1400–1150 BC), situated on an island in the lagoon to the east of the Ptolemaic town, appears to have been occupied by colonists from the Eastern Mediterranean. The material excavated on the island includes large quantities of Cypriot, Syro-Palestinian, Minoan and Mycenaean potsherds, indicating extensive trading contacts between the Aegean region and the north African coast at the time of the Egyptian New Kingdom (c.1505–1070 BC). The earliest traces of Egyptian occupation in the area are the remains of a fortress built by Ramesses II (c.1290–1224 BC) at Zawiyat Umm el-Rakham, about 20 km to the west of Paraetonium.

D. White: ‘The 1985 excavations on Bates’ Island, Marsa Matruh’, JARCE 23 (1986), 51–84; ––––: ‘Provisional evidence for the seasonal occupation of the Marsa Matruh area by Late Bronze Age Libyans’, Libya and Egypt, ed. M.A. Leahy (London, 1990), 1–14.

IS

Mersin (Yümüktepe) Neolithic and Chalcolithic tell-site near the southern coast of Turkey, at the western edge of the plain of Adana, which was excavated by John Garstang (1953). The presence of

HASSUNA, HALAF and UBAID ceramics in the

Chalcolithic levels has enabled the site’s chronological sequence to be synchronized with sites in Mesopotamia. The stratum dating to the mid-5th millennium BC (level XVI) contained the remains of a mud-brick fortress surrounded by a thick enclosure wall complete with towered gateway and slit windows. Although the fortress was somewhat smaller than the earlier citadel at HAÇILAR, its defensibility was greatly enhanced by its location at the summit of the Neolithic settlement mound; the surviving piles of sling-pellets indicate the principal weapon used by its defenders. Each of the houses consisted of a single room and a walled courtyard.

394 MERSIN

A larger multi-roomed building to the south of the gate was perhaps occupied by the ruler of the settlement. The fortress was destroyed by fire in the late Chalclithic but the site was re-settled in the Middle Bronze Age and subsequent occupation continued until the Islamic period.

J. Garstang: Prehistoric Mersin (Oxford, 1953); I.E.S. Edwards, C.J. Gadd and N.G.L. Hammond, eds.:

Cambridge Ancient History I/1, 3rd edn (Cambridge, 1970), 317–26.

IS

Mesolithic (Middle Stone Age) Period sandwiched between the Palaeolithic (Old Stone Age) and Neolithic (New Stone Age), and often taken to begin with the onset of the Holocene at the end of the last Würm glaciation and to end, at various times in various regions, with the advent of food production. This rather awkward definition reflects the retarded interest shown in the period by early archaeologists: for a long time the term Mesolithic was simply a catch-all for the uninteresting time between the glories of Palaeolithic art and the economic and social ‘revolution’ of the Neolithic. Graham Clark (1980) records the reasons why the term Mesolithic tended to be avoided by archaeologists (e.g. Childe) earlier this century, and charts the first uses of the term.

A more positive definition of the period is that it begins with the invention of geometric microliths; the interval between the MAGDALENIAN and this shortened Mesolithic is then reclassified as the EPIPALAEOLITHIC. This can confuse the wideranging reader, however, as the term Mesolithic is rarely employed in the archaeology of southeast Europe, north Africa and south-west Asia. Instead ‘Epipalaeolithic’ is generally used to describe any assemblages after the main Würm glaciation that have a microlithic component. Furthermore microliths can occur in non-Mesolithic contexts (see

MICROLITH).

Mesolithic cultural adaptions. Like the other major divisions of prehistory, the Mesolithic is associated with fundamental socio-economic (as well as technological) changes. Some authorities (e.g. Kozłowki 1973, p.332) have regarded the term Mesolithic as synonymous with the particular type of hunting, fishing and gathering economy that evolved as a response to post-glacial environmental changes such as afforestation. This adaption is most marked in northern and western Europe, where from c.8000 BC to c.6000 BC a rise in temperature led to the end of dry, open cold environments in favour of dense woodlands, especially of hazel. The great

herd animals died away in favour of forest-loving fauna such as boar and roe deer. The flooding of the North Sea and the creation of the English Channel, separating Britain from Europe, were only the most dramatic events in a general flooding of low-lying coastal areas and river valleys.

In early accounts of the Mesolithic, the disappearance of the specialized herd-animal hunting economy as a result of this climatic change seemed to explain the period’s ‘cultural impoverishment’ – i.e. the absence of rich naturalistic art and impressive stone and bone industries. This change in material culture is now seen in a more positive light, as a gradual and successful adaptation to a more broadly based economy and more varied diet. The economic and material culture advances made during the Mesolithic include extensive forest clearance and an associated technology of mattocks, and tree-felling axes; elaborate seasonal scheduling of resource exploitation; domestication of the dog; the use of the bow and the development of microlithic technology; the development of river canoes and sea-going craft together with sophisticated fishing gear including the first evidence for nets and hooks; skis; and long-range exchange networks evidenced by the spread of Mediterranean obsidian and Polish chocolate-coloured flint. Furthermore, while Mesolithic assemblages are rarely visually impressive, microliths originally formed the cutting edge of a sophisticated and adaptable composite tool-type that made a far more efficient use of flint resources than its Palaeolithic predecessors. An important point is the proportion of arrowheads in Mesolithic assemblages (up to 60% in Tardenoisian assemblages), which is distinctly higher than in the Magdalenian and has led to the characterisation of the Mesolithic as ‘essentially the era of hunting with a bow’.

The components of the diversifying Mesolithic economy show great variation from region to region, and the new methodological approach of FORAGING THEORY is increasingly applied to try to explain these complex strategies. In the Pyrenees and in many areas of northern and western Europe, red deer (e.g. STARR CARR) and wild pigs became a principal prey, while at sites in both northern and southern Europe (e.g. FRANCHTHI) there is evidence for specialized marine fishing. The impressive shellfish middens of the ASTURIAN and ERTEBØLLE economies attest to intense, but probably seasonal, exploitation of coastal resources. There is general agreement that the Mesolithic economy made increasing use of plant foods, although, hazelnuts aside, the direct evidence for this remains relatively puny. Some scholars have