A Dictionary of Archaeology

.pdf

been tempted to see ‘pre-adaptations’ to the coming agricultural revolution in the intensifying use of plant resources, suggesting that a primitive form of animal husbandry developed in the Mesolithic. They also point to the domestication of the dog, the development of storage facilities and associated semi-sedentism, and the social developments reflected in the advent of ‘cemeteries’ in some regions and the increasing deposition of grave goods. See also discussion in

STATES 1.

J.G.D. Clark: The Mesolithic settlement of northern Europe

(Cambridge, 1936); S.K. Kozłowski, ed.: The Mesolithic in Europe (Warsaw, 1973); G. Clark: Mesolithic prelude

(Edinburgh, 1980, 3–5; M. Zvelebil, ed.: Hunters in transition: Mesolithic societies of temperate Eurasia and their transition to farming (Cambridge, 1986); C. Bonsall, ed.: The Mesolithic in Europe (Edinburgh, 1989); G.L. Peterkin et al. eds: Hunting and animal exploitation in the Later Palaeolithic and Mesolithic of Eurasia, Archaelogical Papers of the American Anthropological Association 4. (1993).

RJA |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Qermez Maltai |

Tepe |

Shanidar |

|

|

|

||

Dera |

|

Gawra |

Zawi Chemi |

|

|

|

|

|

Khorsabad |

|

|

|

|||

Tell |

|

Tell Arpachiyah |

|

|

|

||

Taya |

|

|

|

|

|||

Nineveh Tell Balawat |

|

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|

|

|||

|

Tell |

Tell Nimrud |

Zarzi |

|

|

|

|

|

Hassuna |

Karim Shahir |

|

|

|

||

Umm Dabaghiyah |

|

|

|

||||

|

Jarmo |

|

|

||||

|

Hatra |

Assur |

Nuzi |

|

|

|

|

Yarim Tepe + |

i |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Tell Maghzalya TTigrisis |

|

|

I R A N |

||||

|

|

|

|

|

|||

|

Samarra |

|

|

|

|

Bisitun |

|

|

|

|

|

Tepe Asiab |

|||

|

Tell es-Sawwan |

|

Tell Abada |

Tepe Sarab |

|||

Euphrates |

|

|

Khafajeh |

Choga Mami |

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Dur Kurigalzu |

Tell Asmar |

Tepe Guran |

||||

N |

|

Tell |

Tell Agrab |

|

|

||

|

Harmal |

Ishchali |

|

|

|||

|

|

Sippar |

|

Ctesiphon |

|

Tepe |

|

|

|

Baghdad |

Tell Uqair |

|

|||

|

|

Babylon |

Jemdet Nasr |

|

Sabz |

||

|

|

|

|

Kish |

|

Tepe Ali Kosh |

|

|

|

Borsippa |

Abu Salabikh |

||||

|

|

|

|

||||

|

|

|

|

|

Nippur |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Isin |

Tell Fara |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

I R A Q |

|

|

|

Telloh |

TiTigrisis |

|

|

|

|

Lagash |

|

|||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Larsa + Tell elAwayli |

||

|

|

|

Hajji Muhammed |

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

Ubaid |

Ur |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Eridu |

|

|

S A U D I |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

A R A B I A |

0 |

|

100 km |

|

|||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

KUWAIT |

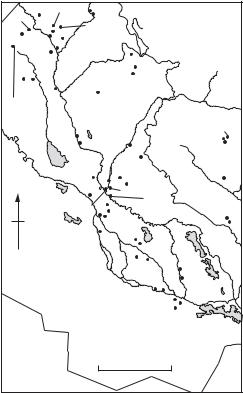

Map 25 Mesopotamia Major sites in Mesopotamia which are mentioned in the main text or have individual entries in the Dictionary.

META-DECISION MAKING |

395 |

||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

Prehistory |

|

|

|

|

|

Palaeolithic period |

70,000 – |

12,000 |

BC |

||

Epipalaeolithic period |

12,000 |

– 9300 BC |

|||

Mesolithic period |

|

9300 |

– 7500 BC |

||

Aceramic Neolithic period |

|

7500 |

– 6000 BC |

||

Pottery Neolithic (Proto-Hassuna) |

|

6000 |

– 5800 BC |

||

Hassuna period |

|

5800 |

– 5500 BC |

||

Samarra period |

|

5600 |

– 5000 BC |

||

Halaf period |

|

5500 |

– 4500 BC |

||

Ubaid period |

|

5000 |

– 3800 BC |

||

History |

|

|

|

|

|

Uruk period |

|

4300 |

– 3100 BC |

||

Jemdet Nasr period |

|

3100 |

– 2900 BC |

||

Early Dynastic I |

|

2900 |

– 2750 BC |

||

Early Dynastic II |

|

2750 |

– 2600 BC |

||

Early Dynastic III |

|

2600 |

– 2350 BC |

||

Lagash Dynasty |

|

2570 |

– 2342 BC |

||

Akkadian Dynasty |

|

2317 |

– 2150 BC |

||

Ur III period |

|

2150 |

– 2000 BC |

||

Isin-Larsa period |

|

2025 |

– 1763 BC |

||

First Dynasty of Babylon |

|

1894 |

– 1595 BC |

||

Old and Middle Assyrian periods |

|

1800 |

– |

884 BC |

|

Mitannian empire |

|

1480 |

– 1300 BC |

||

Second Dynasty of Isin |

|

1157 |

– 1026 BC |

||

Second Dynasty of the Sealand |

|

1026 |

– 1005 BC |

||

Assyrian empire |

|

883 – 612 BC |

|||

Ninth Dynasty of Babylon |

|

713 – 626 BC |

|||

Neo-Babylonian (Chaldaean) Dynasty |

625 – 539 BC |

||||

Achaemenid period |

|

538 – 331 BC |

|||

Macedonian period |

|

330 – 307 BC |

|||

Seleucid period |

|

305 – |

64 BC |

||

Parthian (Arsacid) period |

|

250 BC – AD 224 |

|||

Sasanian Dynasty |

|

AD 224 – 651 |

|||

|

|

|

|

|

|

Table 14 Mesopotamia Chronology of

Mesopotamia.

Mesopotamia Region of western Asia roughly corresponding to modern Iraq. The name Mesopotamia (‘between the two rivers’) refers to the dependence of this large area on the rivers Euphrates and Tigris, both of which flow from Anatolia down to the Persian Gulf.

See AKKAD, ASSYRIA, BABYLON, CHALDAEANS,

DIYALA REGION and SUMER.

H. Frankfort: The art and architecture of the ancient Orient, 4th edn (Harmondsworth, 1970), 20–2, 138–40; M. Roaf:

Cultural atlas of Mesopotamia and the Ancient Near East

(New York and Oxford, 1990); H. Crawford: Sumer and the Sumerians (Cambridge, 1991), 73–6; J.N. Postgate:

Early Mesopotamia: society and economy at the dawn of history (London, 1992).

meta-decision making see DECISION

THEORY

396 METATE

metate A flat or trough-like stone slab, used with a handstone (mano) to grind softened corn kernels into a flour.

PRI

meteoritic iron (China) see T’AI-HSI-TS’UN

Mexica see AZTECS

Miamisburg Large conical earthen mound in southern Ohio, which is the largest ADENA (Early WOODLAND c.1000–200 BC) burial mound in the state, measuring at least 90 m in diameter and over 24 m high when first investigated during the mid-19th century. Archaeological investigation of the site is so far limited to the excavations undertaken by local citizens in 1869, consisting of a shaft descending from the top of the mound to 0.6 m below its base. This effort located a human burial 2.5 m below the mound top and a feature consisting of overlapping flat stones situated about 7 m below the mound summit.

Anon.: ‘The Indian Mound, Miamisburg, Ohio’, OAHSP 14 (1905), 346–7.

RJE

Michelsberg-Pfyn see PFYN

Microblade Tradition Early cultural tradition of the northern Northwest Coast of North America, dating to c.7500–2500 BC, which was typified by the presence of microblade technology and the near absence of bifacial tools. It probably derived from

the PALEO-ARCTIC TRADITION of interior Alaska,

which appears to have emerged several hundred years earlier. The Microblade Tradition is found in the territory occupied by speakers of Tlingit, Haida, and Athabascan-Eyak languages, and may constitute the material culture of the ancestors of these peoples, who introduced microblade technology into northern North America from Siberia. Microblade technology spread south from this region to already occupied sites such as NAMU. The earliest known Microblade Tradition sites are Hidden Falls (Davis, 1989) and Ground Hog Bay, while the remains at Chuck Lake (Ackerman et. al 1985) and the Queen Charlotte Islands are slightly later; their locations are indicative of a maritime tradition.

R.L. Carlson: ‘The far west’, Early man in the New World, ed. R.S. Shutler (Beverly Hills, 1983), 73–96; R.E. Ackerman, K.C. Reid, J.D. Gallison and M.E. Roe:

Archaeology of Heceta Island: A survey of 16 timber harvest units in the Tongass National Forest, Southeastern Alaska

(Pullman, 1985); S.D. Davis: The Hidden Falls site, Baranof Island, Alaska Anthropological Association Monograph (Fairbanks, 1989).

RC

microburin see MICROLITH

microlith Small flint blade, or fraction of blade, often defined as less than 5 mm long and 4 mm thick. Microliths are regarded as the archetypal tool technology of the MESOLITHIC. However, it is now recognized that some industries in the Upper Palaeolithic also manufactured microliths – although they form a much smaller fraction of the lithic assemblages. For example, microliths occur to a limited extent in the MAGDALENIAN, and quite substantially in other Upper Palaeolithic tool-kits (e.g. the Zarzian assemblages in the Zagros, for instance at SHANIDAR, and the CAPSIAN of North Africa). Microliths can be made by striking a very small core (just like making a normal flint blade), or by taking a larger blade, notching it, and then snapping a small portion off. This latter process produces tiny waste chips known as microburins and is known as the ‘microburin method’. Single microliths were sometimes used as the tip of an implement, weapon or arrow. However, multiple microliths also seem to have been hafted together to form composite cutting edges on tools.

RJA

Micronesia see OCEANIA 2

microwear see USE-WEAR TRACES

midden settlement see KHARTOUM

MESOLITHIC

Middle Missouri Tradition Tradition of the Plains Village period which begins in about AD 1000 and has direct cultural continuity with the Mandan Indians. Compact villages of earthlodges where a duel subsistence strategy of corn agriculture and bison hunting was practiced are found along the Missouri River and its tributaries from Iowa to North Dakota. The villages were fortified and occasionally show evidence of conflict. Settlements shifted through time several hundred miles up the Missouri River, apparently because of warfare with the Arikara Indians. The area vacated by the villages

was occupied by Coalescent Tradition sites attributed to the Arikara.

W. Wood: An interpretation of Mandan culture history. River Basin Survey Papers 39, Bulletin 198, Bureau of American Ethnology, Smithsonian Institution (Washington, D.C., 1967); D. Lehmer: Introduction to Middle Missouri archeology. Anthropological Papers 1, National Park Service (Washington, D.C., 1971); R. Windham and E. Lueck: ‘Cultures of the Middle Missouri’, Plains Indians, AD 500–1500, ed. K.S. Schlesier (Norman, 1994) 149–75.

WB

middle-range theory Theoretical and methodological development introduced by the American archaeologists Lewis Binford (1968, 1977, 1981) and Michael Schiffer (1972) as a possible means of bridging the gap between archaeological data and general theory (i.e. the establishment of testable hypotheses and COVERING LAWS). The term ‘middle-range theory’ was first coined by Binford, who argued that in order to make robust inferences, archaeology ‘must develop an appropriate language and instruments for measuring variables . . . in the archaeological record’. Such a language and instruments – or mid- dle-range theory – would be devised and tested in a range of intellectual contexts. It could then be applied to justify inferences in other instances, helping archaeologists to avoid simply building up ‘post hoc accommodative arguments’ (Binford 1981). Moreover, the inferential techniques comprising middle-range theory would be specifically archaeological, and suited to linking observations of archaeological data to interpretation. They would provide a tested and certain platform on which more general theories (for example, about social dynamics) could be postulated and tested. During the 1970s and 1980s, the attempt to build and apply a body of middle-range theory was a significant part of the broader movement towards a PROCESSUAL

ARCHAEOLOGY.

A key example of middle-range theory – and perhaps its most lasting endeavour – was the attempt to build a body of theory that explained

SITE FORMATION PROCESSES. In building

these theories, it became clear that most middlerange theory depended on ACTUALISM or ETHNOARCHAEOLOGY to elucidate the logical links between human behaviour and the found archaeological site. Binford (1984), for instance, has used middle-range theory to explore the possibility that many of the supposedly cultural aspects of the archaeological record in the Lower Palaeolithic (such as big-game hunting by early hominids) are

MIDDLE-RANGE THEORY 397

actually the result of natural site formation processes. However, it has been suggested (e.g. Wylie 1989) that ethnoarchaeological studies characteristically rely too heavily on the biases and research agenda of the individual investigator. It has also been pointed out that present-day analogies can only be applied to the past if sufficient aspects of culture or nature are assumed to have been constant over the course of time.

Since the early 1980s, and especially in Europe,

proponents of POST-PROCESSUAL ARCHAEOLOGY

have either abandoned middle-range theory on the grounds of its supposed excessive scientism (Shanks and Tilley 1987) or transformed it into a set of approaches geared to the complexities and particularities of a specific set of archaeological remains (rather than attempting to identify a set of broadly applicable dynamics). There have also been attempts to argue that middle-range theory was doomed to failure for formal reasons; Joseph Kovacik (1993: 31–2), for instance, uses the arguments of the French philosopher J.F. Lyotard to suggest that middle-range theory is a ‘translation device, yet translation is only operable between two genres of discourse within a single phrase universe, and not between two phrase universes’.

In assessing the contribution of middle range theory, it is important to be remember the dual objective of its original proponents. Even critics acknowledge that there has been some success in terms of amassing a body of theory of use to archaeologists when making ‘low level’ interpretations of archaeological evidence, especially concerning noncultural site formation processes. Attempts to build a body of theory dealing with how archaeological data relates to cultural processes have not proved successful in terms of building secure COVERING LAWS; however, the original project aimed only to produce a body of theory that was applicable beyond the particular, and most critics concede that attempts to test middle-range theory have proved useful in forging a more explicit and disciplined approach to building ethnographic analogies.

In the second important aim – to link the growing body of middle range theory to general theory in a way that would allow grander economic and social theories to be tested – even many processual archaeologists admit that the project is incomplete. The debate centres around whether the incompleteness is inevitable: outside the natural sciences, general theories gain plausibility through such a complex relationship with data and other theory sets that, some argue, middle-range theory in its strictest sense will only ever prove to be a small part of the process of verifying (or refuting) them.

398 MIDDLE-RANGE THEORY

L.R. Binford: ‘Some comments on historical versus processual archaeology’, SJA 24/3 (1968), 267–75. M.B. Schiffer: ‘Archaeological context and systemic context’, AA 37/2 (1972), 156–65; L.R. Binford, ed.: For theory building in archaeology (New York, 1977); L.R. Binford:

Nunamiut ethnoarchaeology (New York, 1978); ––––, ed.: Bones: ancient men and modern myths (New York, 1981);

––––: Faunal remains from Klasies River Mouth (New York, 1984); L.M. Raab and A.C. Goodyear: ‘Middle range theory in archaeology: a critical review of origins and applications’, AA 49 (1984), 255–68; M. Shanks and C. Tilley: Social theory and archaeology (Cambridge, 1987); M.A. Wylie: ‘The dilemma of interpretation’, Critical traditions in contemporary archaeology, ed. V. Pinsky and A. Wylie (Cambridge, 1989); I. Hodder: Reading the past: Current approaches to interpretation in archaeology, 2nd edn (Cambridge, 1991); P. Kosso: ‘Method in archaeology: middle range theory as hermeneutics’, AA 56/4 (1991), 621 ff; J.J. Kovacik: ‘Archaeology as dialogue: Middle Range Theory and Lyotard’s concept of phrase’, ARC 12/1 (1993), 29–38; B.G. Trigger: ‘Expanding middlerange theory’, Antiquity 60/264 (1995), 449–58.

IS

Middle States (Chung-kuo, Zhongguo) Chinese geographical term which is most usefully applied to those ‘princely states’ (chu-hou) that were under Chou feudal suzereignty along with the ROYAL DOMAIN in the 1st millennium BC (see CHINA 2,

EASTERN CHOU and WESTERN CHOU). The

identification of the geographical locations of the ‘states’ themselves has proved difficult. In the philosophical works Meng-tzu and Hsün-tzu, the term is used in a similar way, but in the Ta-hsüeh [The great learning] and the Shi-chi [Memoirs of the historian] – particularly the latter – the Middle States are defined in direct contrast to the ‘barbarian’ regions lying outside the borders of the ‘states’. There is only one instance of the phrase in contemporary inscribed bronzes; it suggests the

and adjacent states, but there is no

H.G. Creel: The origins of statecraft in China (Chicago, 1970), 196, note 1.

NB

migration period Chronological term used in Medieval Archaeology to describe the period between the 5th and 7th centuries when the Roman empire was gradually displaced by ‘barbarians’. The material culture of the phase is reminiscent of that of the late Roman period in Asia and eastern Europe.

Martin Carver, ed.: The age of Sutton Hoo (Woodbridge, 1992).

Millaran culture see LOS MILLARES

Milogradian Iron Age culture of the 7th to 3rd centuries BC, situated in the catchment area of the upper Dniepr river (i.e. northern/central Belarus and the neighbouring area of western Russia and northern Ukraine). The settlements usually take the form of hillforts (gorodisˇcˇe) and are located on the upper river terraces, and on hills in the wetland areas. They are of considerable size (15,000–20,000 sq. m) and often include two rows of fortifications (turf walls and ditches). The inner enclosures are often densely packed with rectangular (4 × 4 m) houses, built of wooden posts and with hearths. The outer enclosure tends to have few houses and was probably intended for corralling animals. Several types of spearhead, iron belt and bronze bracelet have direct analogies in the assemblages of Central Europe. A hoard near the village of Gorshkovo (near Mozyr, southern Belarus) contained 11 bronze and silver bracelets of La Tène-type dated to the 5th–3rd centuries BC. Contact with SCYTHIAN groups further south is documented by numerous finds of Scythian-style arrowheads, ear-rings and hammer-headed pins.

All the sites include slag, fragments of crucibles and blacksmith’s instruments, denoting the local smelting and forging of iron. The rate of domesticates (mainly cattle and horse) in the faunal remains varies between 70 and 90%. Numerous finds of sickles and querns, as well as the impressions of grains (wheats, barley, millet) reveal a highly developed agricultural economy. Both surface graves and kurgan barrows are known; the burial rites included cremation and inhumation. No less than 10 cemeteries have been found: one of the largest, Gorshkovo, included 70 shallow ovalshaped graves with cremated human remains, fragments of ceramics and iron implements (arrowheads, rings and pins). Cemeteries with kurgan barrows are also known, e.g. Duboi, near Brest. One of the barrows contained a grave with the remains of two adults and one child; the grave goods included a golden ear-ring, an iron arrowhead and fragments of a hand-made vessel, suggesting that this was an elite burial.

P.N. Tretyakov: Finno-urgy, balty i slavjane [The FinnoUgrians, Balts and Slavs] (Moscow and Leningrad, 1966); V.F. Isaenko et al.: Ocˇerki po arheologii Belorussi (Essays on the archaeology of Belarus] (Minsk, 1970).

PD

IS |

Mimbres see MOGOLLON |

Minaeans see ARABIA, PRE-ISLAMIC

mindalá Corporate, mainly hereditary, group of professional traders specializing in long distance trade of gold, cotton and luxury goods of late prehispanic northern Ecuador.

F. Salomon: ‘Pochteca and mindalá: a comparison of longdistance traders in Mesoamerica and Ecuador’, Journal of the Steward Anthropological Society 9: 1–2 (1977–8), 231–46.

KB

Minoan civilization Civilization of Bronze Age Crete, identified by Sir Arthur Evans after a series of excavations between 1921 and 1935 at the palace and city site of KNOSSOS. Based on the ceramic material from Knossos, Evans divided the Minoan chronology into three main phases: Early (c.3000–2000 BC), Middle (2000–1550 BC) and Late (1550–1100 BC); the phases are defined in stylistic terms and the precise chronology remains contentious.

During the Early phase, before 2000 BC, Minoan culture is believed to have developed independently, perhaps with influence from the Troad, though the archaeological evidence for this period is scant aside from some impressive THOLOI and rectangular tombs that housed increasingly elaborate grave goods (including cult figurines and gold jewellery). From 2000 BC, palaces developed in association with towns, and Crete began to develop the first true civilization of Europe. Substantial fragments of the first major palaces (2000–1600 BC) have been discovered at Knossos, Mallia and Phaistos. Like the later palaces, each is defined by extensive storage rooms often with massive storage jars or pithoi filled with oil, corn and wine; paved ‘public’ areas; finely built or decorated ‘reception’ rooms; and concentrations of luxury materials and craft items. Sealings (clay impressed using carved seal-stones) and inscribed tablets, apparently used for administration, are also present. Although the architectural complexes such as Knossos are called ‘palaces’, it is by no means certain that they were ruled by secular kings; it is equally possible to imagine political or religious oligarchies, or some more subtle political mechanism. With the development of these early palaces, however, Crete is clearly divided up into centralized palace economies (see below); in the early stages, and perhaps throughout most of the following centuries, the palaces seem to have been politically independent of each other while culturally and economically interlinked.

MINOAN CIVILIZATION 399

Around 1600 BC, these first palaces were destroyed – apparently by earthquakes. They were almost immediately rebuilt, and the visible remains today at sites such as Knossos, Phaistos, Mallia and Zakros are largely those of the post-1600 BC complexes. At Knossos, the rebuilding included extensive use of ashlar masonry, stone and wooden pillars, and elegant doorways. The new palace included impressive architectural features such as the paved and colonnaded ‘Grand Staircase’, leading up through three storeys. The palace walls were carefully engineered with foundations of large stone blocks and walls with timber lacing to minimize the effect of tremors, while light wells and verandahs kept the palace airy and open; there is evidence for drains and fresh-water piping. Walls were plastered or finished with gypsum, and the reception and (possibly) cult rooms were decorated with wallpaintings.

Writing seems to have been devised locally by the Minoans, developing from a stylized pictographic script with linear symbols. Linear A script was widely used in Crete, at Phylakopi, Ayia Irini, THERA etc; although it has not been deciphered, the signs show some similarities with Linear B and it was probably used for much the same purposes. Linear B, which probably developed from Linear A, perhaps at Knossos, seems mainly to have been used to record ownership of goods and for administrative purposes – there is no evidence of religious or diplomatic use (Ventris and Chadwick 1973).

Minoan religion is still largely mysterious. The presence of lustral basins and the quasi-religious ritual depicted in many Minoan murals has led some to consider the ceremonial rooms of the palaces as shrines or ritual centres rather than as secular ‘reception rooms’. Outside the palaces, from the earliest period hilltops and caves seem to have sometimes become special places for making votive offerings (including clay figurines). Some sites have yielded numerous figurines of animals and humans in worship poses. Evans believed Minoan religion centred around a single goddess of fertility, but this is now discounted – a pantheon of more or less local deities seems more likely.

Perhaps the most remarkable of the Minoan arts was that of wall-painting. There is fragmentary evidence from the late Neolithic period on, but the finest examples are from the Middle Minoan period at KNOSSOS and THERA. There is a wide variety of themes, from monkeys and birds depicted at Knossos, and the many human and divine scenes, to the famous scenes of youths ‘bull-leaping’. The style is essentially naturalistic, graceful and fluid; it inspired, but is distinct from, the more static and

400 MINOAN CIVILIZATION

formal MYCENAEAN style of mural painting. Other Minoan artforms include elaborate carved stone vessels, and figurines cast in bronze and other materials, for example the bare-breasted ‘goddesses’ wreathed in snakes made from faience from the temple repositories in Knossos. Hard-stone seals were also manufactured; used for ornament as well as sealing, the drilled designs include mythical beasts such as the griffin, and divinities.

The widespread influence of Minoan civilization is apparent at sites such as THERA. Minoan art and the concept of the ‘palace economy’ fundamentally influenced the development of the MYCENAEAN civilization of the Greek mainland, which developed from about 1550 BC. From the mid-15th century BC (Late Minoan period) the Mycenaeans came to dominate Crete and the Aegean. The Mycenaean influence is manifest in a growing Mycenaean-style of wall-painting at Knossos – for example, the ‘throne-room’ design – and the use of Linear B (which is related to ancient Greek). While it is often assumed that the Mycenaeans exerted political and economic control over some of the palace economies, the nature of their hegemony is still debated.

In around 1425 BC, virtually all the known sites on Crete were destroyed by fire and were then abandoned. The volcanic eruption on Santorini (Thera) was once believed to have caused this wave of destruction, but the eruption is now dated to at least a century or so too early and this theory has been abandoned. The only palace to survive was Knossos, which seems to have been occupied for a further generation or two, arguably by an elite that shows a marked increase in Mycenaean influence – particularly in the adoption of Linear B script, deciphered by Michael Ventris as Mycenaean Greek.

The palace economies as ‘redistributive centres’. It seems clear from the evidence of archives and the massive storage rooms that palaces such as Knossos gathered together and controlled much of the agricultural and craft produce of the economy. It is often assumed that the palaces therefore functioned as the nodal point of a ‘redistributive economy’, with a political or quasi-religious elite bringing together surpluses which could be redistributed to ameliorate the uncertainties of agricultural production. To keep control of the surpluses and to keep a tally of the work and reward of craftsmen, a more sophisticated writing system – Linear A – replaced the earlier hieroglyphic system. If the ‘redistributive’ model of the palace economy is accepted, one implication is that storage centres might have become vulnerable to control by an elite – who per-

haps institutionalized and exaggerated the process for their own benefit. The further implication is that this elite subverted a part of this surplus to support an increasingly specialized, and dependent, ‘service’ economy of administrators and craftsmen. There is relatively little evidence of Minoan society outside the major centres, but a limited number of excavations suggest that smaller Minoan settlements may have had distinctly larger ashlar buildings at their centre which may have controlled the settlements for the benefit of larger centres; ‘villa’ type buildings without associated settlements may also have dotted the countryside, organizing and controlling the pressing of olives and grapes. THERA, although Minoan-influenced rather than strictly Minoan, provides the most detailed evidence for how a street in a Minoan settlement might have looked. The importance of international trade to the palace system is increasingly clear. The workshops depended upon imported tin and copper

– various stores of ox-hide ingots have been discovered. Recent discoveries at TELL EL-DABðA (ancient Avaris) in the Nile delta, including an apparent Minoan sanctuary with wall-paintings of bull-leapers, suggest that a distinct colony of Cretan merchants may have existed there in the 16th century BC. Minoan pottery is known from as far south as Aswan, and Cretans (‘Keftiu’) are pictured in a few Egyptian wall paintings.

A.J.Evans: Palace of Minos at Knossos (London, 1921–36); J.D.S. Pendlebury: The archaeology of Crete (London, 1939); M. Ventris and J. Chadwick: Documents in Mycenaean Greek (Cambridge, 1973); G. Cadogan:

Palaces of Minoan Crete (London, 1976); H. Van Effenterre: Le palais de Mallia et al cité minoenne (Rome, 1980); M.S.F. Hood and D. Smyth: Archaological survey of the Knossos area (London, 1981); P.P. Betancourt: The history of Minoan pottery (Princeton, 1985); J.W. Graham: The palaces of Crete (Princeton, 1987); R. Hägg and N. Marinatos: The function of the Minoan palaces (Stockholm, 1987); P. Halstead: ‘On redistribution and the origin of the Minoan – Mycenaean palatial economies’, Problems in Greek prehistory, ed. E.B. French and K.A. Wardle (Bristol, 1988), 519–30; M. Bietak: ‘Minoan wallpaintings unearthed at ancient Avaris’ Egyptian Archaeology: Bulletin of the EES 2 (1992), 26–8; J.W. Myers et al.: The aerial atlas of ancient Crete (London, 1992); K.A. Wardle: ‘The palace civilizations of Minoan Crete and Mycenaean Greece, 2000–1200 BC’, The Oxford illustrated prehistory of Europe, ed. B. Cunliffe (Oxford, 1994) 202–43.

RJA

Minyan ware Distinctive ware characteristic of the Middle Helladic period (2000–1400 BC) in Greece. The first wheel-made ware in Greece, and

closely related to wares found in Asia Minor in the same period, it is very finely produced with a polished surface and elegantly angular forms including ‘wine goblet’ and two-handled bowls. Minyan ware was named by Schliemann following his excavations at ORCHOMENOS in Boeotia, Greece

– the seat of the legendary King Minyas. The earliest and most common Minyan ware, produced from the end of the 3rd millennium BC until around 1500 BC, is fired so as to be uniformly grey (Grey Minyan); a rarer variant (Yellow Minyan) appeared around 1700–1600 BC and continued to be produced into the 15th century BC. Minyan ware was used contemporaneously with other forms including painted, handmade forms – Minyan itself is undecorated aside from wheel-turned ridging – and in its latest stages it is found associated with Mycenaean ware.

RJA

Mirgissa (anc. Iken?) Egyptian site of the 2nd and 1st millennia BC, located in Lower Nubia, immediately to the west of the southern end of the 2nd Nile cataract, 350 km south of modern Aswan (now submerged under LAKE NASSER). The site was dominated by a large rectangular Middle Kingdom fortress surrounded by a ditch and inner and outer enclosure walls. Covering a total area of some 4 ha, it was the largest of 11 fortresses built in the reign of the Egyptian Middle Kingdom pharaoh Senusret III (c.1878–1841 BC) between the 2nd and 3rd cataracts, protecting the royal monopoly on trade from the south. On the island of Dabenarti, about 1 km east of Mirgissa, are the remains of a small unfinished fortified mud-brick garrison, apparently of similar date.

D. Dunham: Second cataract forts II: Uronarti, Shalfak, Mirgissa (Boston, 1967), 141–76; J. Vercoutter: Mirgissa, 3 vols (Paris and Lille, 1970–6); S.T. Smith: Askut in Nubia (London, 1995).

IS

Mi Son (Mi-son’n) The greatest of all CHAM religious centres, situated in the province of Quangnam in central Vietnam. Building commenced in the 7th century AD under Vikrantavarman I; numerous sanctuaries, characterized by singlechambered structures surrounded by rectangular walls, were added until the reign of Jayaindravarman in the 11th century AD.

M.H. Parmentier: Inventaire descriptif de monuments Cams de l’Annam (Paris, 1918).

CH

MITANNI 401

Mississippian Term used to describe archaeological complexes distributed across the southern Midwest and Southeast in North America that share certain similarities in artefact inventories, architectural features, subsistence practices and sociopolitical organization. Although dates vary from one region to another, Mississippian societies had developed in many places by AD 1000. Some of them were contacted by mid-16th century Spanish expeditions. These were sedentary agricultural peoples who grew maize and other cultigens, hunted game, fished, and collected wild plants. They lived in ranked societies known as chiefdoms, although some were more populous and powerful than others. Principal sites were marked by mounds which served as platforms for important buildings, including residences for highly ranked people, charnel houses for the bones of their ancestors, and community-related structures.

B.D. Smith, ed.: Mississippian settlement patterns (New York, 1978); D.G. Anderson: The Savannah River chiefdoms: political change in the late prehistoric Southeast

(Tuscaloosa, 1994); J. Muller: Mississippian political economy (New York, 1991).

GM

Mitanni HURRIAN kingdom in northern Mesopotamia and the Levant which flourished during the 14th and 15th centuries BC. The heartland of Mitanni appears to have been the fertile area between the upper Tigris and Euphrates now known as the plain of el-Jazira, which forms a natural link between northern Iraq and Syria. Although Mitanni was at first assumed to be a separate entity from the land of the Hurrians (see Contenau 1934), the two are now generally agreed to have been virtually synonymous by the mid-2nd millennium BC at least (Liverani 1962).

At its height, the empire of Mitanni severely curbed Egyptian ambitions in Syria (see MEGIDDO) and also checked the resurgence of ASSYRIA and BABYLONIA in Mesopotamia. However, by the late 14th century BC, when the rulers of Mitanni were in correspondence with the Egyptian pharaohs of the 18th dynasty (see EL-AMARNA), the Mitannian sphere of influence had begun to diminish, probably in direct response to the growth of the Hittite empire.

Although much of the general population of Mitanni was clearly Hurrian, there is some controversy regarding the ethnic origins of their ruling elite. Many of the names of the rulers and deities are Indo-Aryan rather than Hurrian, and the term applied to the aristocracy as a whole, maryannu

402 MITANNI

(‘young warriors’) may derive from an Indo-Aryan word. However, it has been argued that such IndoAryan connections were already characteristic of the areas occupied by the Mitannians rather than their elite in particular (Diakonoff 1972). In archaeological terms, Mitannian sites are characterized by fine white-painted pottery (‘Nuzi ware’) and objects made from frit. A small Hurrian temple has been excavated at the Syrian site of TELL BRAK, which was evidently a Mitannian town of some importance.

Neutron activation analysis and the search for Washshukanni. The location of the capital of Mitanni, Washshukanni, may be Tell Fakhariya, but this is a matter of some debate, and the two bestdocumented Mitannian sites (TELL ATCHANA and NUZI) lie at the western and eastern edges of the kingdom respectively. In the 1940s and 1950s, three archaeological expeditions were launched specifically in order to find Washshukanni (McEwan and Moortgat working at Tell Fakhariya, and Lauffray at Tell Chuera), but none produced any conclusive evidence.

In the 1970s, the problem was instead approached with the use of

ANALYSIS. This method is most commonly applied to pottery, but in this case it was used to attempt to determine the geographical origins of a set of 13 clay cuneiform letters sent from Tushratta, king of Mitanni, to the Egyptian king Akhenaten in the mid-14th century BC (Dobel et al. 1977). It was hoped by this means to arrive at an approximate idea of the location of Washshukanni, where the letters (found at EL-AMARNA in the Middle Egypt) might be assumed to have originated. The distinctive ‘Tushratta fingerprint’ resulting from the analysis of the 13 tablets could therefore be compared with a number of different locations in the region. There were marked differences between the ‘Tushratta’ and Tell Fakhariya profiles, particularly with regard to the proportions of nickel, thorium and hafnium, thus suggesting that this site should perhaps be finally abandoned as a possible location of Washshukanni. Although there was evidence to suggest a reasonable amount of diversity in terms of the chemical composition of clays in different parts of the Khabur triangle, none of the sampled clays within this region could be matched up with the ‘Tushratta’ profile. The geographical position of Washshukanni therefore remains something of an enigma, until clay samples are sampled from other areas associated with Mitanni, such as the Middle Khabur valley.

G. Contenau: La Civilization des Hittites et des Mitannienes

(Paris, 1934); M. Liverani: ‘Hurri e Mitanni’, Oriens

Antiquus 1 (1962), 253–7; I.M. Diakonoff: ‘Die Arier im Vorderen Orient: Ende eines Mythos’, Orientalia 41 (1972), 91–120; A. Dobel, F. Asaro and H.V. Michel: ‘Neutron activation analysis and the location of Wassukanni’, Orientalia 46 (1977), 375–82; H. Klengel: ‘Mitanni: Probleme seiner Expansion und politische Struktur’, Revue hittite et asianique 36 (1978), 94–5; G. Wilhelm: The Hurrians (Warminster, 1989);

For further bibliography see HURRIANS.

IS

Mitla see ZAPOTEC

Mixtecs One of two major cultural and linguistic groups in the Oaxaca region of Mesoamerica (the other group being the ZAPOTECS), the Mixtecs occupied the western portions of the state during the Late Postclassic period (c.AD 1200–1521). Known for exquisite metal and lapidary work and their CODICES that tell of the genealogies of their kings, the Mixtecs also used parts of

at times in the Late Postclassic.

R. Spores: The Mixtec kings and their people (Norman, 1967); K.V. Flannery and J. Marcus, eds: The cloud people: divergent evolution of the Zapotec and Mixtec civilizations

(New York, 1983); ‘Special section: rethinking Mixtec codices’, AM 1/1 (1990) [whole journal]; J. Monaghan:

The covenants with earth and rain: exchange, sacrifice and revelation in Mixtec sociality (Norman, 1995).

PRI

moa Large flightless bird of the ratite family found only in New Zealand and hunted to extinction by the 18th century (at the latest). Large moa hunting and butchery sites are common in the South Island of New Zealand.

A. Anderson: Prodigious birds: moas and moa hunting in prehistoric New Zealand (Cambridge, 1989).

CG

mobiliary art (art mobilier, portable art)

Generic term used to describe smaller movable art objects. In the Upper Palaeolithic, it contrasts with the parietal or cave art of the same period. The term itself implies no particular style or period within the Upper Palaeolithic: it embraces the smaller sculptures, such as the ‘VENUS FIGURINES’, clay objects, the engraved and sculpted bone and antler tools, and other decorated objects such as PLAQUETTES. Although mobiliary art is defined as art that is portable, it should not be assumed that all these different types of objects (especially the plaquettes) were actually moved from site to site. Mobiliary art has been found in various regions

across the whole Euroasian land mass, from western France to Siberia, and thus has a far wider distribution than parietal art; as it is generally recovered from an archaeological context, and is often made of organic material, it is usually also easier to date.

J. Clottes, ed.: L’art des objets au paléolithique 2 vols (Paris, 1990).

RJA

model (mathematical) A simplified representation of a complex reality, ranging from small ‘tactical’ issues such as the break-up of pottery, to large ‘strategic’ problems such as the spread of agriculture. The nature of the simplification depends on the uses of the model. Consisting of one or more mathematical statements and/or equations describing chosen aspects of a topic, it may range from a simple descriptive statement about a single VARIABLE (e.g. the size of pottery fragments) to a large interrelated set of equations which are intended to reproduce the workings of some system or process (e.g. a foraging system, see LATION). Models form an essential link between

archaeological THEORY and DATA (see STATISTI-

CAL CYCLE); the extent to which they are made explicit depends on the complexity of the situation and the numeracy of the archaeologist. Many methods of statistical analysis are based on a model in which a certain VARIABLE has a certain

STATISTICAL DISTRIBUTION; if this condition is

not met (i.e. the model is incorrect), the use of the technique may not be valid. Techniques for examining whether a DATASET is adequately described by a particular model are known as GOODNESS-OF-FIT tests. If no model (distribution) can be found which appears to fit a particular dataset, it can be studied by the use of

PARAMETRIC STATISTICS, which do not rely on

such assumptions.

D.L. Clarke: Models in archaeology (Cambridge, 1972); A.J. Ammerman and L.L. Cavalli-Sforza: ‘A population model for the diffusion of early farming in Europe’ The explanation of culture change, ed. C. Renfrew (London, 1973), 343–57 [spread of farming]; C. Renfrew, ed.: The explanation of culture change (London, 1973); J.E. Doran and F.R. Hodson: Mathematics and computers in archaeology (Edinburgh, 1975), 26–8; C.R. Orton: Mathematics in archaeology (Glasgow, 1980), 20–1 [general].

CO

mode of production Marxist term used to describe the various socioeconomic stages through which different cultures are thought to pass, i.e. tribal, ancient, asiatic, slave, feudal, capitalist and

MOGOLLON 403

socialist (Marx and Engels 1962: 43–56). According to Marx himself, writing in 1859, ‘The mode of production in material life determines the general character of the social, political and intellectual processes of life’ (Marx and Engels 1962: 362). Some archaeologists (particularly Soviet and neoMarxist researchers, See RUSSIA 3 and MARXIST ARCHAEOLOGY) have used this concept to describe the means by which cultural transformations occur. Thus Dean Saitta and Art Keene (1990) have studied prehistoric village formation in the PUEBLO culture of north America, identifying a communal mode of production which does not lead to egalitarianism (as traditional Marxism might have suggested).

K. Marx and F. Engels: Selected works I (Moscow, 1962); J. Friedman: ‘Tribes, states and transformations’, Marxist analyses and social anthropology, ed. M. Bloch (London, 1975); J. Friedman and M. Rowlands, eds: The evolution of social systems (London, 1978); D. Saitta and A. Keene: ‘Politics and surplus flow in prehistoric communal societies’, The evolution of political systems: sociopolitics in small-scale sedentary societies, ed. S. Upham (Cambridge, 1990), 203–24.

IS

Mogador see AFRICA 1

Mogollon Major prehistoric culture of the American Southwest, which lasted from the end of the Archaic period to the arrival of the Spanish in AD 1540. It was defined in 1936 by Emil W. Haury on the basis of extensive surveys of the mountains of east-central Arizona and west-central New Mexico in 1931. In 1933 Haury also excavated Mogollon Village along the San Francisco River and, in 1934, Harris Village in the Mimbres Valley. Haury’s original definition was of a Mogollon culture characterized by true pithouses and coil-and-scraped, brown pottery – polished plain (Alma Plain), red-slipped (San Francisco Red), and decorated red-on-brown (Mogollon Red-on- brown). After AD 1000 Haury felt that the Mogollon lost their identity through assimilation with the ANASAZI. Current researches subscribe to Erik Reed’s interpretation that a separate Mogollon identity can be traced after AD 1000 and in some regions up to the abandonment of the Arizona mountains around AD 1400. These distinctive characteristics include: PUEBLO village layout focusing inward on a plaza; rectangular KIVAS within room blocks; primary extended inhumation of the deceased; vertical-occipital head deformation; the three-quarter groove axe; and brown

404 MOGOLLON

corrugated pottery often with patterned, incised or painted designs.

The Mogollon developmental sequence is most simply divided into three periods. The Early Pithouse period began around AD 200, with the addition of plain brown pottery to a late Archaic artefact assemblage and ended in the AD 600s around the time that red-on-brown decorated pottery appeared. The Late Pithouse period ends with construction of masonry pueblos around AD 1000 in the Mimbres Valley of New Mexico and from 100 to 200 years later, as pueblo architecture moved westward into the Arizona mountains. The Mogollon Pueblo period ends with the abandonment of the mountains by AD 1400. The latest tree-ring dates attributable to the Mogollon are in the 1380s.

The Mogollon were a hunting, gathering and sometimes gardening people, adapted primarily to the mountain uplands and secondarily to the adjacent desert lowlands of Arizona and New Mexico. A southern boundary in the present-day Mexican states of Sonora and Chihuahua is undefined. Loosely defined regional subdivisions or branches are a product of archaeologists working within the

paradigm of CULTURE-HISTORICAL THEORY in ex-

ploring isolated areas with long, continuous occupations. These areas include New Mexico: the Mimbres Valley (Mimbres branch), San Francisco Valley (Pine Lawn Branch); Arizona: Point of Pines (Black River branch), San Simon Valley (San Simon branch) and Forestdale Valley (Forestdale branch). The hemispherical ceramic bowls of the Mimbres branch (often used as funerary offerings), bearing depictions of people, animals naturalistic scenes and geometric forms, are unique among prehistoric North American cultures.

The Jornada branch defined in the El Paso area seems to have been a distant relative of the mountain-adapted Mogollon. By abandoning the mountains to take up full-time farming, the Mogollon merged archaeologically with the other pueblo farmers of the northern Southwest. The Mogollon cannot be linked positively to a historical group. The major Mogollon sites in Arizona are Bear, Bluff, Crooked Ridge, Turkey Creek and GRASSHOPPER; and those in New Mexico are Harris, Mogollon Village, Cameron Creek, Galaz, Mattocks and Swarts.

J.J. Brody: Mimbres painted pottery (Santa Fe, 1977); S.A. LeBlanc: The Mimbres people (London, 1983); E.W. Haury: Mogollon culture in the Forestdale Valley, eastcentral Arizona (Tucson, 1985); J.J. Reid and D.E. Doyel, eds: Emil W. Haury’s prehistory of the American Southwest

(Tucson, 1986); J.J. Reid: ‘A Grasshopper perspective on

the Mogollon of the Arizona Mountains’, Dynamics of southwest prehistory, ed. L.S. Cordell and G.J. Gumerman (Washington, D.C., 1989), 65–97.

JJR

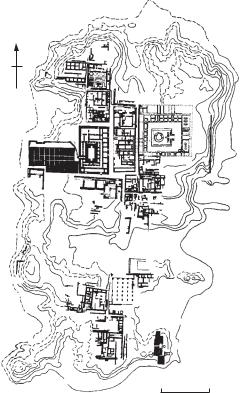

Mohenjo-Daro Large multi-mound urban centre of the INDUS CIVILIZATION, dating to the 3rd millennium BC and located beside the Indus River in southern Pakistan. Excavators since the 1920s have included John Marshall (1921–2), Ernest Mackay (1927–31), Mortimer Wheeler (1950) and George Dales (1964–6). The total area of the site is about 200 ha, and the two principal mounds (a smaller ‘citadel’ to the west and a larger, lower eastern mound) cover an area of about 85 ha. This dual mound plan is found at other sites of the INDUS

CIVILIZATION, including HARAPPA and

KALIBANGAN and is often taken as evidence of rigid and highly formalized town planning. While

N

‘College’

(Stupa)

Bath

Granary

Stair

Tower

Assembly

Hall

|

Fortifications |

0 |

50 metres |

Figure 35 Mohenjo-Daro Plan of the citadel of Mohenjo-Daro. Source: B. and R. Allchin: The rise of civilization in India and Pakistan (Cambridge University Press, 1982), fig. 7.10.