Beginning Ubuntu Linux - From Novice To Professional (2006)

.pdf18 |

C H A P T E R 2 ■ A H I S T O R Y A N D P O L I T I C S L E S S O N |

Summary

This chapter has detailed the history of Linux and explained its origins. It also explained why Linux came into being. We looked at how Linux formed one of the building blocks of a political movement geared toward producing software that can be shared.

We discussed the creator of Linux, Linus Torvalds. We’ve also looked at the massive input the GNU Project has made and, in particular, that of its philosopher king, Richard Stallman.

In the next chapter, we move on to look at what you can expect from day-to-day use of Linux.

C H A P T E R 3

■ ■ ■

The Realities of Running Linux

So now that you’ve learned about the politics, history, and personalities behind Linux, only one question remains: what’s Linux actually like when used day to day? What should the average user expect from the experience?

These are the questions I hope to answer in this brief chapter.

Learning to Use Linux

What should you expect from Linux once you’ve installed it? Well, it’s a little like running Windows, except there are no viruses, fewer crashes, and no inexplicable slowdowns.

In addition, you have complete control over the system. This doesn’t mean Linux is necessarily complicated. It’s just that you have the control if you wish to make use of it. We’ll look into this in the later chapters of this book.

Most software you use under Windows has at least one equivalent under Ubuntu, installed by default. It’s unlikely that you’ll need to download or install any additional software and, even if you do, you’ll probably find it’s available for free.

In most cases, the Linux swap-ins are at least as powerful and easy to use as their Windows alternatives. Tabbed browsing in the Mozilla Firefox web browser lets you visit more than one site at once, for example, without needing to have a lot of browser instances running, as you do with Microsoft Internet Explorer. The Evolution program has a search routine that lets you look through your e-mail messages quickly for a variety of criteria, and it puts the features in a similar Microsoft product to shame.

Does this sound too good to be true? There is just one caveat. Linux isn’t a clone of Windows and doesn’t aim to be. It has its own way of doing certain things, and sometimes works differently from Windows. This means that many people experience a learning curve when they first begin using Linux.

■Note Several Linux distributions aim to mimic Windows pretty faithfully. For example, Xandros, Lycoris/lx, and Linspire copy the look and feel of Windows to the extent that (allegedly) some people are unable to tell the difference.

19

20 |

C H A P T E R 3 ■ T H E R E A L I T I E S O F R U N N I N G L I N U X |

But in just a few weeks after your move to Linux, everything will start to seem entirely normal. Most of the time, you won’t even be aware you’re running Linux. Of course, some patience is required during those initial few weeks. Linux can be illogical and frustrating; on the other hand, so can Windows. We simply got used to it.

Who Uses Linux?

Who uses Linux? The myth from the old days is that it’s only for techies and power users. When you needed to put everything together by hand, this was clearly true. But modern distributions make Linux accessible to all. It’s no exaggeration to say that you could install Linux on a computer Luddite’s PC and have that person use it in preference to Windows.

Up until quite recently, Linux was largely seen as a developer’s tool and a server operating system. It was geared toward programmers or was destined for a life running backroom computers, serving data, and making other computer resources available to users.

To this end, Linux continues to run a sizable proportion of the computers that make the Internet work, largely because it provides an ideal platform for the Apache web server, as well as various databases and web-based programming languages. This has lead to the LAMP acronym, which stands for Linux, Apache (a web server), MySQL (a database), and PHP, Python, or Perl (three programming languages that can be used in an online environment).

Despite its technical origins, recent years have seen a strong push for Linux on desktop computers. Linux has stepped out of the dark backrooms, with the goal of pushing aside Microsoft Windows and Mac OS in order to dominate the corporate workstation and home user market.

Running Linux on the desktop has always been possible, but the level of knowledge required was often prohibitively high, putting Linux out of the reach of most ordinary users. It’s only comparatively recently that the companies behind the distributions of Linux have taken a long, hard look at Windows and attempted to mirror its user-friendly approach. In addition, the configuration software in distributions like Ubuntu has progressed in leaps and bounds. Now, it’s no longer necessary to know arcane commands in order to do something as simple as switch the screen resolution. The situation has also been helped by the development of extremely powerful office software, such as OpenOffice.org and Koffice.

Is Linux for you? There’s only one way of finding out, and that’s to give it a go. Linux doesn’t require much of you except an open mind and the will to learn new ways of doing things. You shouldn’t see learning to use Linux as a chore. Instead, you should see it as an adventure—a way of finally getting the most from your PC and not having to worry about things going wrong for reasons outside your control.

Linux puts you in charge. You’re the mechanic of the car as well as its driver, and you’ll be expected to get your hands dirty every now and then. Unlike with Windows, Linux doesn’t hide any of its settings or stop you from doing things for your own protection; everything is available to tweak. Using Linux requires commitment and the realization that there are probably going to be problems, and they’re going to need to be overcome.

However, using Linux should be enjoyable. In his initial newsgroup posting announcing Linux back in 1992, Linus Torvalds said that he was creating Linux “just for fun.” This is what it should be for you.

C H A P T E R 3 ■ T H E R E A L I T I E S O F R U N N I N G L I N U X |

21 |

Getting Hold of Linux

Getting hold of Linux is easy. You’ll already have spotted the version of Ubuntu packaged with this book. Ubuntu is the main focus of this book, and I consider it to be one of the very best versions of Linux out there. It’s ideal for both beginners and power users, and it really does match the functionality offered in Windows. It includes several easy to use configuration tools, which makes changing your system settings a breeze. For example, the Synaptic Package Manager software can automate the download and installation of new software with just a few clicks.

Ubuntu is also a very good-looking distribution. You’ll find your friends and colleagues “wowing” when they happen to pass by and glance at your PC!

Quite a number of Linux distributions are available. If you want to explore other Linux distributions as well as Ubuntu, by far the most fuss-free method of getting hold of Linux is to pop over to your local computer store (or online retailer) and buy a boxed copy. You can choose from Red Hat, SUSE, Mandrake, Libranet, TurboLinux (if you want foreign language support, although nearly all commercial distributions do a good job of supporting mainstream languages), and many others. Many distributions come on more than a single CD—typically up to four CDs at the moment. Some versions of Linux come on DVD.

■Caution Bearing in mind what I’ve said about the sharing nature of Linux, you might think it possible to buy a boxed copy of Linux and run off copies for friends, or even sell them for a profit. However, you shouldn’t assume this is the case. A minority of distribution companies, such as Xandros and Linspire, incorporate copyrighted corporate logos into their distributions that place restrictions on redistribution. Sometimes they include proprietary software along with the Linux tools, which you cannot copy without prior permission. However, in many cases, reproducing the CDs in small volumes for friends or for use on workstations in a company environment is permitted.

Many of the Linux distributions are also available to download free of charge. In fact, many community-run distributions—such as Slackware, Debian, Fedora, and Gentoo—are only available this way (although you can often buy “homemade” CDs from smaller retailers, who effectively burn the CDs for you and produce makeshift packaging). If your PC has a CD-R/RW drive and you have some CD-burning software under Windows (such as Nero), you can download an ISO image and make your own installation CD from it.

■Note An ISO image is a very large file (typically 700MB), which you can burn to CD. This CD is then used to install Linux.

22 |

C H A P T E R 3 ■ T H E R E A L I T I E S O F R U N N I N G L I N U X |

Using Ubuntu

Ubuntu is a relatively young Linux distribution. It is based on and is still closely allied with the Debian distribution, like many versions of Linux. Debian has been in existence for almost as long as the Linux kernel and embraces the spirit and philosophy of Linux, which says software should be shared and made available to anyone who wants it.

Ubuntu takes this one step further. Its goal is to give anyone in the world access to an easy- to-use version of Linux, regardless of geographical location or physical abilities. Ubuntu supports a large number of languages, so it can be used in most countries around the world. In addition, it includes accessibility tools, so it can be used by partially sighted, deaf, or disabled people.

From the very start, Ubuntu’s creators decided it would always be free of charge and would always be freely available. Unlike with many versions of Linux, no commercial version of Ubuntu exists (although it is possible to pay for various services, such as support, if you wish).

But perhaps Ubuntu’s greatest strength is its community, which extends across the world. If you have a question about Ubuntu, you’ll find hundreds of people willing to help. Just as the software is designed to be shared, a strong belief within the Ubuntu community is that knowledge should be shared, too.

It might come as no surprise that Ubuntu is an ancient African word that roughly translates as “humanity to others.” In South Africa in particular, “Ubuntu” is a way of life that advocates acceptance and compassion towards others. The Ubuntu philosophy is one of the underpinnings of post-apartheid South Africa and spreads into political spheres as well as everyday life. The Ubuntu version of Linux is an attempt to bring this spirit to the world of computer software.

Ubuntu is primarily geared toward desktop users, although with a little adapting, it can also be used to run server computers.

Ubuntu is designed to be easy to use. Anyone who has used Windows or Mac OS will feel right at home. It features every piece of software you could wish for or would find within a wellequipped modern operating system. It includes a web browser, an e-mail client, instant messaging software, an office suite, a graphics editor, and much more. And don’t think that these are cutdown versions designed to lure you into purchasing the full version later on. In every case, they’re full-featured pieces of software that give proprietary programs a run for their money.

Perhaps more important, Ubuntu is very user-friendly. Updating the system can be done with just a few clicks of the mouse, as can downloading and installing new software.

Summary

This chapter explained what you can realistically expect when using Linux every day. It also discussed the kind of company you’ll be keeping in terms of fellow users.

You learned how people usually get hold of Linux. Of course, with this book, you already have a version of Linux, Ubuntu, which was introduced in this chapter.

This completes the general overview of the world of Linux. In the next part of the book, you’ll move on to actually installing Linux on your hard disk. This sounds more daunting than it actually is. The next chapter gets you started by explaining a few basic preinstallation steps.

P A R T 2

■ ■ ■

Installing Ubuntu

C H A P T E R 4

■ ■ ■

Preinstallation Steps

The first part of this book discussed the pros and cons of using Linux as part of your day-to- day life. It was intended to help you evaluate Linux and understand what you’re buying into should you decide to make it your operating system of choice. Now, we move on to actually installing Linux and, specifically, Ubuntu, which is included with this book on a CD-ROM.

Installing any kind of operating system is a big move and can come as something of a shock to your PC. However, Ubuntu makes this complicated maneuver as easy as it’s possible to be. Its installation routines are very advanced compared to previous versions of Linux, and even compared to other current distributions.

What does saying that you’re going to install Ubuntu actually mean? This effectively implies three things:

•Somehow all the files necessary to run Ubuntu are going to be put onto your hard disk.

•The PC will be configured so that it knows where to find these files when it first boots up.

•The Ubuntu operating system will be set up so that you can use it.

However, in order to do all this and get Ubuntu onto your PC, you must undertake some preparatory work, which is the focus of this chapter.

Understanding Partitioning

Chances are, if you’re reading this book, your PC already has Windows installed on it. This won’t present a problem. In most cases, Ubuntu can live happily alongside Windows in what’s called a dual-boot setup, where you can choose at startup which operating system to run. However, installing Ubuntu means that Windows must make certain compromises. It needs to cohabit your hard disk with another operating system—something it isn’t designed to do.

The main issue with such a situation is that Windows needs to shrink and make some space available for Ubuntu (unless you install a second hard disk, which is discussed later in this chapter). Ubuntu isn’t able to use the same file system as Windows, and it needs its own separately defined part of the disk, which is referred to as a partition. All of this can be handled automatically by the Ubuntu installation routine, but it’s important that you know what happens.

All hard disks are split into partitions, which are large chunks of the disk created to hold operating systems (just like a large farm is partitioned into separate fields). A partition is usually multiple gigabytes in size, although it can be smaller. You can view your disk’s partitions using the Disk Management tool in Windows XP and Windows 2000, as shown in Figure 4-1. You can

25

26 |

C H A P T E R 4 ■ P R E I N S T A L L A T I O N S T E P S |

access this tool by opening Control Panel, clicking the Administrative Tools icon, selecting Computer Management, and then choosing Disk Management.

Figure 4-1. You can view your disk’s partitions using Windows XP’s Disk Management tool.

Most desktop PC systems have just one partition, unless the user has specifically created new partitions. As mentioned, Ubuntu needs a partition of its own. During installation, Ubuntu needs to shrink the main Windows partition and create a fresh partition alongside it (actually, it creates two partitions; the extra one is used to hold the swap file).

In addition, the Ubuntu installation routine writes a new boot sector (also known as a boot loader). The boot sector is located at the very beginning of the disk and contains a small program that then runs another program that lets you choose between operating systems (and therefore partitions) when you first boot up.

■Note Not all Linux distributions have the ability to repartition the hard disk. In fact, at the time of writing, it’s pretty rare. Most expect to simply take over the entire hard disk, wiping Windows in the process (although they’ll always ask the user to confirm this beforehand). The ability to repartition a disk is just one of the reasons that Ubuntu is among the best Linux distributions currently available.

C H A P T E R 4 ■ P R E I N S T A L L A T I O N S T E P S |

27 |

Of course, Ubuntu cannot shrink a Windows partition that is packed full of data, because no space is available for it to reclaim.

UBUNTU AND WINDOWS FILE SYSTEMS

One of the benefits of dual-booting Linux and Windows is that Ubuntu lets you access the files on the Windows partition. This is quite handy and facilitates the easy exchange of data.

If the Windows partition is FAT32—used on Windows 95, 98, Me, and (sometimes) XP—then Ubuntu can both read and write files to the partition. However, if the file system is NTFS—used with Windows NT, 2000, and (sometimes) XP—then Ubuntu will make the file system available as read-only. Because of this, you might consider converting your NTFS Windows partition to FAT32 before you install Ubuntu (but be aware that doing so means you lose some of the security and performance features of NTFS). Microsoft doesn’t include a tool that lets you do this automatically, but you can use third-party disk partitioning programs like Symantec’s Partition Magic (www.symantec.com) to convert your file system.

Freeing Up Space

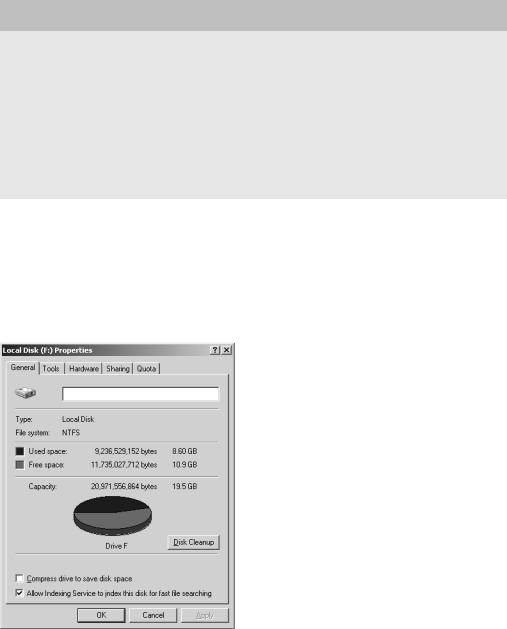

The first step before installing Ubuntu alongside Windows is to check how much free space you have in your Windows partition. To see the amount of free space you have, double-click My Computer, right-click your boot drive, and select Properties. The free space is usually indicated in purple on a pie-chart diagram, as shown in Figure 4-2.

Figure 4-2. Ubuntu needs free disk space in which to install, so you might need to clean up your Windows partition.