Cleaver Economics The Basics (Routledge, 2004)

.pdf

employed all operate on changing the banking system’s reserve assets and, thereby, having a multiplied impact on the economy’s total money supply. (With a money multiplier of 10 times reserves, for example, if the central bank can engineer a reduction in commercial bank reserve holdings of, say, 12 million units then the economy’s money supply will fall by 120 million.)

1 Changing Reserve Requirements. The central bank (hereafter known as the Bank) is the fulcrum of a country’s banking system and can insist on a minimum reserve assets ratio that all financial intermediaries must observe. Suppose, however, the Bank wishes to boost consumer spending to stave off recession. If the Bank decreases this ratio then, with their existing reserves, all intermediaries can immediately issue more loans and thereby increase the money supply (see Box 5.5). The money multiplier increases. Conversely, if the Bank increases the ratio, the money multiplier must fall, loans must be called in and the money supply must contract.

2 Open Market Operations. Rather than enforcing a change in legal requirements, a more indirect (and more popular) measure to employ is what is known as open market operations.

The Bank in its every day dealings goes into open money markets and lends money to some institutions and borrows from others. The FINANCIAL INSTRUMENTS it uses to do this are variously called bonds, bills, or securities – all specific promises to pay sums of money over different time periods. Now if the bank buys a bond, it is in effect exchanging cash with some other agent in return for a legally binding promise of future payment. The agent selling thus receives cash which that institution can now place in its own commercial bank account.

Box 5.5 The money multiplier: an example

Suppose financial intermediaries hold one dollar in reserve for every eight loaned out. That represents a reserve assets ratio of 12.5 per cent. If they now change to a ratio of 10 per cent, one dollar in reserve can support ten dollars in circulation. That is, banks can now loan out an extra two dollars for every one they hold in reserve. More customers can be given more money and encouraged to spend it.

© 2004 Tony Cleaver

By this measure, commercial bank reserves of cash increase and so they can increase the money supply by a multiplied amount.

Conversely, if over a period of time the Bank sells more private bonds and bills than it buys, then clearly there will be a drain on the private sector’s cash reserve into the central coffers. The money supply must therefore be reduced by a multiple of the loss in reserves.

3 The Discount Rate. A third measure that might be used to exercise monetary control is for the Bank to change its discount rate, or the interest rate it charges on its own loans.

With all sorts of traders operating in a modern financial system to buy and sell money, to issue and accept loans, there will naturally evolve a competitive rate of interest. This equilibrium rate will, as in any market, serve to equate demand and supply between commercial dealers.

In free financial markets with no legally enforced reserve ratio to observe nowadays, private bankers have no wish to keep cash reserves above the lowest practicable levels since stockpiling cash earns them no interest – better to loan it out even for short periods if this can earn them something. Reserves can thus be kept at a bare minimum to meet customer demand and if a recognised bank is caught short of cash at any time it can always lend from the Bank at no major cost, providing the discount rate is equal to the going market rate anywhere else.

If the Bank looks like raising its discount rate, however, financial intermediaries have an incentive to keep more cash in their vaults – to avoid having to pay higher than market rates for last resort loans. (Note: If everyone scrambles to increase cash reserves, demand shifts to push up the market price anyway!) Either way, as cash reserves rise the money supply is reduced by a multiplied amount. Fewer loans can be issued.

T H E D E M A N D F O R M O N E Y

The money supply, in theory at least, can be adjusted by the institutions of a country’s banking system. What determines the demand for money?

It depends on the alternatives. People may hold their wealth in the form of non-interest earning money or in the form of some income-earning asset (e.g. bonds, shares, fine art or property). For this reason, Keynes called the demand for money – a perfectly

© 2004 Tony Cleaver

liquid asset, as opposed to demand for other, less liquid assets –

LIQUIDITY PREFERENCE.

For simplicity, we can assume like Keynes that the best alternative to accumulating wealth in the form of money is holding it in risk-less, interest-earning assets such as government bonds. (Such a legally binding promise from the government to pay a fixed sum of interest over a stated period frequently comes in the form of a fancy, gilt-edged document. It is a no-risk, 100 per cent secure investment, unlike promises from some other parties. See junk bonds, Box 5.6.) Thus, the opportunity cost of holding money is the interest forgone in not holding bonds. The higher the interest rate, therefore, the greater the cost of holding money and the lower will be the demand for it.

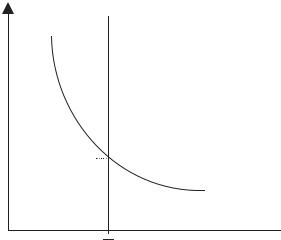

Society’s demand for money can thus be illustrated by a normal demand curve where the rate of interest is the price of money (Figure 5.1).

The demand for money is illustrated by the liquidity preference

–

curve LP. The supply of money M is given by the institutions of the banking system. The equilibrium market rate of interest r* is thus determined by the interaction of the supply and demand curves.

There are, of course, benefits in holding money. Keynes identified the transactions motive and the precautionary motive, amongst others.

The rate of interest

Supply of money

r*

LP

Quantity of money

Quantity of money

M

Figure 5.1 Liquidity preference and the market rate of interest.

© 2004 Tony Cleaver

T h e Tr a n s a c t i o n s M o t i v e

People demand money for its use in conducting trade or transactions. We all need money to finance our spending over each month though most of us also divert some monthly income into savings or investments such as pension funds. How much money I demand for financing transactions depends on the general level of prices and the frequency at which I am paid. If all prices doubled, for example, I would need to double the size of my money balances. Similarly, if I were paid on a weekly basis, rather than a monthly basis, I would need to hold smaller money balances. Last, my transactions demand would increase if my real income increased – I would want to spend more money, more often and so would therefore keep larger money balances.

T h e P r e c a u t i o n a r y M o t i v e

People tend to keep a small, stable fraction of their income in money form so as to meet unexpected contingencies. We can all expect something unexpected (!) on which we may need to spend some money – an unanticipated celebration or a need to drown our sorrows. The demand for money for this precautionary motive also tends to be affected by the size of real incomes.

What these motives imply is that as real incomes increase the demand curve for money illustrated in Figures 5.1 shifts forward (just like any other demand curve, see Chapter 2), thus causing an increase in the market price of money if supplies stay constant. Likewise a fall in incomes leads to a shift back in demand and falling interest rates.

A rise in real income is not the only reason why societies might hold more money balances over time. Since financial deregulation swept the Western world in the 1980s there has been much greater competition between banks and all other financial intermediaries, both nationally and internationally. One result of this is that many institutions now offer all sorts of temptations to consumers to open bank accounts. Interest is offered on many sight deposits as well as time deposits and overall the real cost of holding money has decreased significantly over the last twenty years. The incentive to hold bonds and other alternatives to money is correspondingly less (Box 5.6).

© 2004 Tony Cleaver

Box 5.6 Speculative demand, bond prices and the rate of interest

Financial markets allow traders to loan or borrow money over a variety of time periods. For example, you may decide to purchase a bond promising £100 in one year’s time – in which case you are in effect loaning out money for a year. What price would you pay for this bond? If you offer £95 then you have accepted a rate of interest of approximately 5 per cent. If the seller will accept nothing less than 98 then the price of bonds has risen and the rate of interest has fallen. (Thus the price of bonds and the rate of interest are conversely related.)

For all financial assets, key influences are the going market rate of interest, the degree of risk involved in the particular asset being traded and the predicted rate of inflation. If the rate on risk-less government bonds (where there is no chance the government will default) is 5 per cent and the rate of inflation is 2 per cent then the real rate of interest is in effect 3 per cent. (Getting back 5 per cent when inflation has devalued the currency by 2 per cent means you only really earn an extra 3 per cent over the year.) Buying a JUNK BOND from a not so well known trader, you might thus insist on a real rate of 6 per cent or more, depending on your assessment of the risk involved. That is, a nominal rate (including inflation) of over 8 per cent.

A one-year security is not necessarily an illiquid asset. You don’t have to wait for 12 months to get your money back if you change your mind after you have bought it. You can simply sell it tomorrow for whatever price the market values it for. Dealers buy and sell assets of varying dates of maturity like this all the time since it allows a finance house to possess a portfolio of holdings of differing liquidity. (Generally, the more liquid the loan the lower the risk but the lower the rate of interest it earns.)

What happens if you think that the price of bonds (or any other asset you hold in place of cash) will fall in the future, and market rates of interest rise? If you believe that next Thursday the central bank will put interest rates up you will sell bonds now – and thus demand more money today – rather than wait for prices to fall. Going to the markets to sell bonds/demand money for this reason is to express the SPECULATIVE MOTIVE in demand.

© 2004 Tony Cleaver

The central bank sells and then buys back, or ‘repossesses’, bonds and gilt-edged securities before their maturity dates in order to supply the markets with assets of varying liquidity. The Bank can thus use these instruments either in open market operations to try and influence money supplies or to dictate a given discount or repossession (‘repo’) rate. As will be explained in the following section, central banks in fully deregulated and global money markets have really given up on trying to influence money supplies, but what happens in an economy if the Bank does indeed signal a rise or fall in its discount rate? In the first few years of the new millenium, with increasing worries about stagnating economic growth, the USA, the UK and (more lethargically) the European central banks have all cut their interest rates. We need to see why.

M O N E TA R Y P O L I C Y W I T H G L O B A L M A R K E T S

Most economists support the policy of financial deregulation in money markets since greater competition between banks – as with all industry – increases efficiency and brings prices down to the consumer. Opening frontiers to allow foreign banks to compete is just the extension of this principle.

The City of London is one of the world’s major financial centres and the process of deregulation started here back in 1979. The operation of free enterprise in finance, however, once started built up an unstoppable momentum. Breakthroughs in technology helped since it became possible to move money costlessly from one centre to another across the world with just the push of a few buttons. Most money, after all, has no physical form – it is just a record on a computer screen.

Now if banks in one centre can buy and sell money with little government penalty or tax then clearly banks in other centres subject to stricter controls will lose custom and profits. Finance houses in such a situation have usually found ways round central controls since it is in their interest to do so – the end result is that deregulation quickly catches on everywhere.

The problem for central banks is that they must inevitably lose control of their domestic money supplies. Remember that if a commercial bank’s reserve assets can be reduced by the central authorities then it must call in its loans, reduce its money supply,

© 2004 Tony Cleaver

by a multiplied amount. But if a bank loses cash reserves to the central bank and then can compensate for this loss by gaining other liquid assets from alternative sources (overseas if necessary) it no longer has to worry about supporting its existing pattern of longterm loans. Money supplies need not contract. Moreover if all sorts of financial intermediaries can now enter the industry and buy and sell money, the reserves of which institutions does the Bank try to control? Where do you draw the line?

For these two reasons, in a global financial environment, most countries’ central banks have stopped trying to fine-tune their domestic money supplies. If a central bank can no longer monopolise the supply of money in its own backyard, however, it can still affect the money markets by changing its own discount rate. Cutting prices will stimulate demand; raising rates will stifle it.

T h e Tr a n s m i s s i o n M e c h a n i s m

The transmission mechanism by which a change in the central rate of interest impacts on an entire economy can be quite long drawn out but it is still an important influence.

This is particularly so if the change is unexpected. Since speculation is rife in financial markets, the decision of a forthcoming meeting of the central bank committee may have already been built in to the pricing of marketable assets. (Suppose you think the Bank’s rate will come down next week and prompt bond prices to rise from 95 to 98 as explained in Box 5.6. If you are selling bonds today, you will hold out for 98 – bringing forward the fall in the market rate of interest.) Expectations affect everything in modern economies.

If, of course, the Bank is reducing its discount rate to counter a prevailing mood of depression then key to the markets’ reactions will be how the Bank’s actions are interpreted. Is it too little, too late? A signal of official desperation? Or is it a necessary corrective measure that everyone applauds and thus comes as a stimulus to trade sufficient to counter the markets’ gloom? (It is generally accepted that the actions of the US Federal Reserve to reduce its discount rate in a continuing series of cuts from 2001 onwards has helped mitigate an American, and world, economic slowdown.)

A fall in the discount rate will normally be followed by a fall in most other rates of interest in the market place since, as earlier

© 2004 Tony Cleaver

explained, other rates are based around this. All things being equal, falling rates bring a boom in asset prices – from speculative paper to property prices. Mortgages will be cheaper and thus more demand for houses will push their prices up. People will feel wealthier.

With loans coming easier, if manufacturing industry can quickly expand production – or where they retain large stockpiles – there will be more sales of consumer durables. People will buy more cars.

A fall in market rates will bring a reduction in foreign monies entering the economy to be placed in interest-bearing accounts in domestic banks. Less demand for the currency, therefore, will cause a fall in the exchange rate. (This may or may not affect the earnings from export sales or spending on imports, depending on how price-elastic the respective demands are. The country’s balance of payments may thus be affected – see Chapter 6.)

As all these effects cascade through the economy the level of aggregate demand will rise over time. Particularly influential will be the impact on investment. Cheaper bank borrowing means it is less costly to raise funds to invest but an even greater stimulus occurs if business expectations are shifted. If the change in discount rate secures a more optimistic business outlook then investment will rise and a multiplied increase in national income may result (see Chapter 4): Employment will rise and, providing the economy has the capacity to expand, output and incomes will increase and inflation will not result.

E x c h a n g e R a t e s

With global financial markets, note that no one country can implement domestic monetary changes without considering external influences. If a nation places no restriction on money entering or leaving its shores then it must take the consequences. In particular, a country cannot fix its exchange rate with other world currencies, deregulate its financial markets and hope to pursue an independent monetary policy. This is known as the ‘impossible triangle’.

As explained above, reducing domestic interest rates to stimulate domestic demand will result in a DEPRECIATION of the exchange rate. A country can only keep a fixed price of its currency on the FOREIGN EXCHANGE MARKETS if it imposes strict capital controls – that is, prevents dealers from buying and selling the currency in the quantities they desire.

© 2004 Tony Cleaver

Fixing exchange rates of the domestic coinage to major world currencies such as the US dollar or the euro (see the gold standard, Box 5.2) is something that many countries’ governments have desired – now as in the past – as a means of lending stability to their own financial systems.

Especially true with a newly introduced currency that people may not yet have confidence with, if the new paper carries a fixed value in terms of a trusted external currency then dealers are more likely to accept it.

Even with well recognised currencies, fixed exchange rates generally help trade (Box 5.7). For example, if you are planning a foreign

Box 5.7 Discipline in international trade

A fixed exchange rate imposes discipline on central banks and governments.

Consider the following scenario: if a country is losing out in trade – such that export revenues are insufficient to cover import spending – then there are more domestic importers selling the currency than foreigners wanting to buy it. The price or exchange rate of this currency will be expected to fall in a free market or, in a system of fixed exchange rates, a country’s central bank must sell off its gold or foreign currency reserves to cover the difference and thus maintain the fixed rate. No central bank can afford to do this for very long. What a fixed regime ensures therefore, is that the central authorities must do something to address the root of the problem: to prevent the country from living beyond its means and buying more in international trade than it is prepared to sell. (This generally means cutting back on domestic demand and attempting to switch resources to promote export production. It generally implies consuming less – a policy that bankers and politicians like to recommend for others . . .)

The gold standard, when it operated for all trading counties at the beginning of the twentieth century, imposed just this discipline on world economic affairs and some observers with long memories still hark back to these days and the certainties that this system embodied.

© 2004 Tony Cleaver

holiday the last thing you want is continually changing foreign prices – which is exactly what would happen if the exchange rate is floating, not fixed. Whether it is trying to arrange a holiday or to secure a vital business contract, varying prices impose a cost – and thus a disincentive – on trade. Such an argument is particularly relevant if you are in a small country that deals regularly with a big neighbour. With so much business at stake, it is better to fix the exchange rate so everyone knows the costs involved.

F I N A N C I A L C R I S E S

The trouble is, trying to maintain fixed exchange rates at times when global markets question the value of the currency concerned, has been a contributing factor in most modern financial crashes. The East Asian currency crisis in 1997, Russia 1998 and Argentina 2001 are only the most recent at the time of going to press. They are hardly likely to be the last.

At first, international financiers are reassured by fixed exchange rates. The risk in buying foreign securities is reduced if you know that the overseas earnings you later receive will not be devalued by some future fall in price of the currency.

A developing country which perhaps has a change of government and pegs its currency to the dollar, removes restrictions on the international movement of money and pursues prudent financial policies familiar to Western bankers may become very attractive to overseas investors. Especially if it is resource rich, needful of capital and with fledgling industry and commerce welcoming to interested outsiders. Local bankers quick on their feet can now call on far greater supplies of finance if foreign creditors are confident about exchange rates. And it is easy to make money when everyone else is getting in on the act – entrepreneurs find that in setting up a new company in boom times, everybody wants a share and prices on the bonds and securities they issue keep rising. Does it matter that projected future profits are based on scarce or over-optimistic data? If confidence holds, not really. Those people rushing in to get rich quick will not worry if the paper they hold is over-priced – so long as they are confident that they can sell it later for even higher prices. The market succumbs to feverish buying . . . until sometime, somehow, somebody blows the whistle.

© 2004 Tony Cleaver