Cleaver Economics The Basics (Routledge, 2004)

.pdf

economy’ played out under big skies and wide horizons where there is plenty of space and resources for all. Unfortunately, the growth of economic activity has now reached a point where the Earth is better appreciated as a crowded spaceship – where oxygen and other resources are scarce and some of the passengers are being more selfish than others. None of us should now go round like Buffalo Bill: burning the grass, shooting all the bison, using only a fraction of the carcass and leaving the rest to rot.

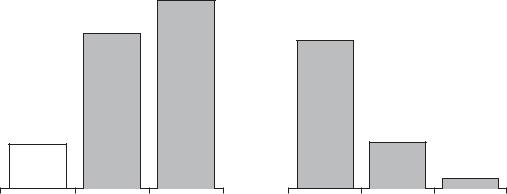

Evidence of how far the Earth’s environment has been degraded is still contested – some claim that we are doing irreversible damage to the planet; others insist that such accusations are wildly exaggerated. There will always be some people who have a vested interest in proclaiming one extreme or the other – all the more reason for economists to get their sums right. Measurement of many of the important variables is very often extremely difficult but here are some data drawn from The Economist magazine and the environmental pressure group WWF (The World Wide Fund For Nature) as shown in Figure 1.3 and Box 1.3, respectively.

Increase in last century |

Numbers remaining today |

1700%

1400%

400%

|

|

|

|

|

World |

|

GDP |

CO |

|

|

|

|

|

2 |

population |

World |

|

emissions |

|

|

80% |

|

|

|

|

|

|

25% |

|

|

|

|

|

5% |

Forest |

areas |

Blue |

whales |

Tigers |

|

|

|

Figure 1.3 Changes in population, output, emissions and native species since 1890.

© 2004 Tony Cleaver

Box 1.3 Case study: Tigers at risk

Less than a century ago, it is estimated that 100,000 tigers ranged across all of Asia from eastern Turkey to the Sea of Japan, from as far north as Siberia down over the equator to Indonesia. Now, 95 per cent of tigers are gone and fragile populations survive in small clusters in India, Indo China and Siberia. While poaching for illegal trade in tiger body parts is a continuing menace, the greater threat to the tiger’s survival comes from loss of habitat and the consequent depletion of its natural prey.

Of eight tiger sub-species, three have become extinct in the last fifty years: The Bali tiger, Javan tiger and Caspian tiger. Of the others, the South China or Amoy tiger was estimated in 1998 to have a population of between 20 and 30 individuals only. Its future looks bleak.

As habitats fragment, the surviving tiger populations become separated from one another and a particular threat is then the loss of genetic diversity. Tiger fertility is reduced, litter sizes fall and cub survival rates decline.

The problem is that tigers compete with humankind in populating some of the most fertile, resource-rich places in East Asia. Look at Indonesia: having lost out in Bali and Java, the remaining battle for tiger survival is taking place in Sumatra. A similar struggle continues in Bengal, whose famously beautiful tiger prowls the little remaining jungle in the IndianBangladesh borders not yet colonised by people hungry for economic development.

The painful reality of economics is illustrated here. Resources are scarce. Natural habitats that support tigers can alternatively support increasing wealth and welfare for human populations. It is easy for distant critics living in foreign cities to cry out in protest and insist that tigers are protected. Who is going to protect the livelihood of millions of poor children in Sumatra or Bangladesh? Only their parents who need the wood that protects the tigers’ habitat . . .

Source: Threatened Species Account, WWF International, May 2002.

© 2004 Tony Cleaver

O P P O R T U N I T Y C O S T

The most fundamental concept in economics is opportunity cost. If you choose to use resources in one employment, then you must sacrifice the opportunity to use them in some other way. It is an old adage: you can’t have your cake and eat it.

This sacrifice is frequently described as a TRADE-OFF. For example, if we use native forests to construct homes, build ships and fuel the fires of industry then society must trade this off against retaining the natural habitat for wild animals to roam free.

North West Europe used to be carpeted from end to end in temperate rainforest. Very little remains today. There is no native, unspoilt natural vegetation left in Western Europe that has remained unexploited by man. Gone too are the bears, wild boar and a host of other species that used to run wild in the forests. But the trees felled in the past built the ships that first circumnavigated the globe, founded the trade and provided the energy that produced the modern industrial age. A much greater human population has now largely replaced the animal population that preceded it.

It is in the nature of economics that sacrifices must be made. The issue therefore becomes one of being as efficient and equitable as possible. Keep the opportunity cost of economic development to a minimum so we do not have to trade-off too much of one to gain more of the other.

The European lion may be extinct though we might yet find ways to protect the Asian tiger. But there are no guarantees. It takes time for society to learn to practise SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT and, in the interim, more species may still die out. The long term aim must not be to preserve all existing species, however, since this would inevitably preclude any further improvement of our own welfare. The opportunity cost in this case would be prohibitive. The appropriate aim is thus to minimise environmental costs such that the CAPITAL STOCK of our planet is not depleted. The garden I bequeath my children may therefore contain a different mix of flora and fauna to that which I inherited but it should nonetheless retain all its phenomenal fertility and productivity. Future generations are thus not denied the opportunity to use the Earth in whatever ways their ingenuity allows.

© 2004 Tony Cleaver

T H E M O D E R N , M I X E D E C O N O M Y

We live in a world of constant change. What consumers demand today they discard tomorrow as tastes and preferences move on; what producers find technically impossible this year is revolutionised next year with the latest breakthrough. In such circumstances, achieving the twin goals of efficiency and equity in any economic system is a never-ending challenge.

Only the most flexible and fleet-footed economic organisations will survive to meet this challenge, as is evident by the demise of inefficient centrally planned Eastern European economies that could not match the growing wealth of their western neighbours. It is also evident in the economic stagnation of nations with inequitable regimes in sub-Saharan Africa and elsewhere which confine riches to a few and thus fail to harness the productive capacity of most of their peoples.

Getting the perfect mix of market systems, government controls and national traditions just right in any one country is frustratingly difficult since there are an infinite variety of combinations and the global economy is moving all the time. But, of course, it is just this endless diversity that makes the world what it is and the study of economics so fascinating.

There is a continual debate, in particular, over the extent to which governments should intervene in markets. It must be emphasised at the outset of this text that markets need government and could not survive without them – the art is in knowing just how far to exert the guiding (corrupting?) influence of central authority and examples will be given throughout the following pages to illustrate this point.

That markets cannot develop without government protection is easily demonstrated. Contrast the experience of a consumer trying to purchase something as basic as a shirt in different cultures. In a modern city store, the buyer would choose the selected item from a range of alternatives on display – all carrying designated price tags on cards which additionally provide information about the shirt size, quality of cloth and design type employed. The customer next takes the shirt across to the sales assistant and quite possibly hands over a plastic card to effect a transfer of money from the consumer’s bank account to that of the store. The buyer signs the

© 2004 Tony Cleaver

till receipt, picks up the packaged item and leaves the store. Sale concluded.

In another culture the process may be very different. The consumer enters the bazaar and is confronted with a wealth of colourful alternatives, none of which appear standard. After a period of indecision, one particular shirt perhaps seems attractive. An eager stallholder – if not already present – soon arrives now and, recognising a potential sale, engages in conversation with the customer pointing out how wonderful this particular product is and how astute his client is in picking out this item so soon. When it comes to price, there is quite a debate. One party starts high; the other much lower. In the process of HAGGLING, the eventual equilibrium price emerges according to the bargaining strength and verbal acuity of the participants. Payment is accompanied by minute examination of the means of exchange proffered. If all goes well, the stallholder accepts the cash and the customer moves away with his purchase, wondering if what he has bought is as good as he hopes it to be and whether the price will subsequently turn out to be exorbitant . . .

The physical characteristics of the shirt in both examples might be exactly the same, though a case can be made for saying that in the latter market place the customer has paid for the social interaction as well as the product.

The economic reason for the differences described here relate to the nature of institutional support for the markets in question. In the second case, much time and effort is devoted to CLIENTISATION: the process by which the two parties become known to one another and their credibility established. Without the back up of a reliable system of contracts and law enforcement, one party can always cheat on a deal and get away with it. To overcome this, personal credibility has to be established with a certain extravagant interaction (hidden agenda: is the other worthy of entering into business with?) otherwise the ‘price’ agreed upon will be all the higher to compensate for the increased risk involved.

If the buyer distrusts the seller then the latter will have to pay the ‘price’ of no deal or gaining less cash than he bargained for. If the seller distrusts the buyer or his currency then he will charge all the more. Better for both parties if they deal with each other frequently and have already established a respectful relationship or, failing that, one comes with the personal recommendation of a third

© 2004 Tony Cleaver

party who is known and respected by both. (Hence the importance of extended family, or a patron, in such societies.)

Without the support of contract law, reliable currency and trust that each is indeed the rightful owner of the property that is to be exchanged, the market society in the second example – however colourful and attractive to the tourist – cannot extend very far. The

TRANSACTION COSTS and INFORMATION COSTS involved limit its scope

to personal trade only between recognised dealers. It is too costly, too risky to engage in transactions with total strangers. This simple market economy will never grow, therefore. It is, indeed, characteristic of what goes on in villages and towns that are found throughout the poorer countries of the world.

How much easier it is to buy products in a modern (albeit impersonal) market economy. Both parties are assured that if they are cheated they have recompense in law. With central authorities providing the essential institutions to protect property and facilitate trade, risk is reduced and market dealers can get on with their business.

Today people can purchase goods and services on the internet which minimises transaction costs and allows greater expansion of commerce. Dealing with strangers is quite normal; one-off trades where you are unlikely ever to see the other party again do not mean you are going to be exploited. Revealing details of your bank account over the phone or on-line is so safe that it has become common practice. It might be impersonal, but it works.

In fact, because it works, it has become more impersonal. Where trust can be taken for granted, the market economy grows. And as it grows it facilitates greater and greater economic specialisation, interdependency and thereby wealth. You can book a foreign holiday, buy the flight tickets, reserve hotel rooms, hire a car and pay for it all without leaving your computer – safe in the knowledge that the tickets will arrive in the post, the car will be waiting at the foreign airport and the hotel room will be ready for you whenever you say. A range of specialised contracts have all been fulfilled across different frontiers, not one party having personal knowledge of the ultimate customer: you. Yet insofar as these trades are successfully concluded, all dealers profit from the arrangement and are encouraged to expand their businesses, offer more services, employ more resources and spread the benefits ever wider.

© 2004 Tony Cleaver

There is a powerful clue here to explain why some communities grow rich and others do not. Where society has evolved institutions to underpin markets and facilitate trade, wealth can be created. Where such institutions are missing, markets do not develop and wealth cannot grow. This is an important conclusion in basic economics and one to which we will return.

Summary

•Economics analyses how societies choose what, how and for whom goods and services are produced.

•Tradition, central planning or free markets can be employed as mechanisms to organise production and distribution.

•The choices made and end results achieved by different economies can be judged according to the efficiency and equity of the processes involved.

•The real or opportunity cost of achieving any goal is measured in terms of what has been sacrificed in achieving it.

•Wealth is created and economies develop insofar as market trade is facilitated and enhanced by institutions that protect property, enforce contracts and minimise risk.

F U R T H E R R E A D I N G

North, D. (1994) ‘Economic Performance Through Time’, American Economic Review, Vol. 84, June pp. 359–68. This is a very accessible article by a recent Nobel Prize winner of how institutions underpin trade and how this accounts for the economic progress of North America in contrast to the stagnation of South America.

Schultz, T. (1964) Transforming Traditional Agriculture, Yale University Press. A classic text on its subject.

Wilbur, C. K. and Jameson, K. P. (1996) The Political Economy of Development and Underdevelopment, McGraw-Hill. Not positive economics but a provocative set of readings that emphasise the exploitation of poorer by richer nations. Note the chapter on El Salvador.

© 2004 Tony Cleaver

World Wide Fund for Nature, www.panda.org. Again, not positive economics but a source of selective information on environmental matters.

World Bank, World Development Report 2002: Building Institutions for Markets. The World Bank publishes an authoritative report each year on a topic of economic importance, reflecting the trends in current academic interest. This issue is recommended if you want to read a more balanced reference on how markets develop.

© 2004 Tony Cleaver

2

P R I C E S , M A R K E T S A N D C O F F E E

Durham Cathedral soars above the centre of the old British market town as it has done for almost a thousand years. But just down the road from the Norman cathedral and the castle that defends it, a new coffee shop has recently opened. Amongst the cluster of shops and stalls which crowd Durham’s market place, this newcomer has now opened its doors to tempt the passer-by with the pungent aroma of fresh-roasted coffee. (At least it has at the time of writing. By the time you read this yet another entrepreneur may well have taken over the business and be displaying fashion wear or computer games or some other such service, which attracts the buying public!)

There are few places on Earth that are not touched by the continual changes of market organisation. Humankind is a restless species and is always seeking out new and better ways to produce things, more and different goods and services to acquire. But by what mechanism is it decided what is produced where, and by whom? How is the organisation of society’s economic affairs carried out?

A hot cup of coffee is a perishable commodity: how come coffee, milk, sugar, skilled labour, specific equipment and every other resource necessary all arrive from their separate origins to deliver a satisfying product to your hand just at the very moment you want it? We take it for granted but a simple cup of coffee represents in fact a complex coming together of a unique set of ingredients that makes up a distinctive and time-sensitive product. Any breakdown in the multiple chains of organisation that are involved in bringing

© 2004 Tony Cleaver

you this good will result in the costly failure to produce anything palatable that anyone would want to buy.

Coffee from Colombia, sugar from the West Indies, milk or cream from a British farm, a china cup and saucer from somewhere local or distant (China?), water from the regional utility, an espresso machine from Italy, local labour and enterprise, plus a variety of other resources that go to make up the total experience of visiting this coffee shop: who organises all these resource flows to bring you a cup of coffee?

T H E P R I C E M E C H A N I S M

Adam Smith called it the Invisible Hand. He wrote in 1776 that each individual’s pursuit of personal gain ensured that, in aggregate, society’s wants are better met this way than if some philanthropic enterprise had indeed set out consciously to organise the same.

Many economists have since shared this view. They argue that the automatic functioning of unrestricted trade and free market pricing will ensure efficient economic organisation that cannot be bettered by the combined actions of any number of well-meaning planners, administrators and public servants.

Prices make up the key signalling mechanism in a market economy that indicates which needs are most urgent, which production strategy should be utilised, who is to be employed and how much they should be paid.

Suppose the tastes of the public change such that they are increasingly interested in buying coffee and health-food sandwiches and are tired of consuming additive-packed hamburgers and technicolour pizzas? Who is best placed to signal this to restauranteurs and fast food producers – government planners or individual consumers?

In a free market, by the pattern of consumer spending, hamburger bars and pizza parlours will lose sales and the owners of coffee shops will be earning extra. Prices of those products out of favour may well fall at first to try and tempt back more custom; prices of those commodities in hot demand may well rise at first as competitive bidding forces them up. But if consumer trends continue there will be an irrevocable change in suppliers’ profits – out of the pockets of loss-making hamburger sellers and into those of coffee shop keepers. If they cannot continue to pay their costs (typically high rents in

© 2004 Tony Cleaver