Mankiw Principles of Macroeconomics (3rd ed)

.pdf

196 |

PART THREE SUPPLY AND DEMAND II: MARKETS AND WELFARE |

|

|

|

|

IN THE NEWS

A Chicken Invasion

But the real agenda, American producers contend, is old-fashioned protectionism.

Agitated Russian producers, whose birds, Russian consumers say, are no match for their American competition in terms of quality and price, have repeatedly complained that the United States is trying to destroy the Russian poultry industry and capture its market. And now American companies fear the Russian producers are striking back. . . .

The first big invasion of frozen poultry [into Russia] came during the Bush administration. . . . The export proved to be very popular with Russian consumers, who dubbed them Bush legs.

After the demise of the Soviet Union, American poultry exports continued to soar. Russian poultry production, meanwhile, fell 40 percent, the result of rising grain prices and declining subsidies.

Astoundingly, a third of all American exports to Russia is poultry, American officials say. . . .

If the confrontation continues, the United States has a number of possible

A THREAT TO RUSSIA?

recourses, including arguing that the Russian action is inconsistent with Moscow’s bid to join the World Trade Organization.

Some experts, however, believe there is an important countervailing force here that may lead to a softening of the Russian position: namely Russian consumers.

Russian consumers favor the American birds, which despite the dire warnings of the Russian government, have come to symbolize quality. And they vote, too.

SOURCE: The New York Times, February 24, 1996, pp. 33, 34.

same. In other words, it can bargain with its trading partners in an attempt to reduce trade restrictions around the world.

One important example of the multilateral approach is the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), which in 1993 lowered trade barriers among the United States, Mexico, and Canada. Another is the General Agreement on

CHAPTER 9 APPLICATION: INTERNATIONAL TRADE |

197 |

Tariffs and Trade (GATT), which is a continuing series of negotiations among many of the world’s countries with the goal of promoting free trade. The United States helped to found GATT after World War II in response to the high tariffs imposed during the Great Depression of the 1930s. Many economists believe that the high tariffs contributed to the economic hardship during that period. GATT has successfully reduced the average tariff among member countries from about 40 percent after World War II to about 5 percent today. The rules established under GATT are now enforced by an international institution called the World Trade Organization (WTO).

What are the pros and cons of the multilateral approach to free trade? One advantage is that the multilateral approach has the potential to result in freer trade than a unilateral approach because it can reduce trade restrictions abroad as well as at home. If international negotiations fail, however, the result could be more restricted trade than under a unilateral approach.

In addition, the multilateral approach may have a political advantage. In most markets, producers are fewer and better organized than consumers—and thus wield greater political influence. Reducing the Isolandian tariff on steel, for example, may be politically difficult if considered by itself. The steel companies would oppose free trade, and the users of steel who would benefit are so numerous that organizing their support would be difficult. Yet suppose that Neighborland promises to reduce its tariff on wheat at the same time that Isoland reduces its tariff on steel. In this case, the Isolandian wheat farmers, who are also politically powerful, would back the agreement. Thus, the multilateral approach to free trade can sometimes win political support when a unilateral reduction cannot.

QUICK QUIZ: The textile industry of Autarka advocates a ban on the import of wool suits. Describe five arguments its lobbyists might make. Give a response to each of these arguments.

CONCLUSION

Economists and the general public often disagree about free trade. In 1993, for example, the United States faced the question of whether to ratify the North American Free Trade Agreement, which reduced trade restrictions among the United States, Canada, and Mexico. Opinion polls showed the general public in the United States about evenly split on the issue, and the agreement passed in Congress by only a narrow margin. Opponents viewed free trade as a threat to job security and the American standard of living. By contrast, economists overwhelmingly supported the agreement. They viewed free trade as a way of allocating production efficiently and raising living standards in all three countries.

Economists view the United States as an ongoing experiment that confirms the virtues of free trade. Throughout its history, the United States has allowed unrestricted trade among the states, and the country as a whole has benefited from the specialization that trade allows. Florida grows oranges, Texas pumps oil, California makes wine, and so on. Americans would not enjoy the high standard of living

198 |

PART THREE SUPPLY AND DEMAND II: MARKETS AND WELFARE |

|

|

|

|

IN THE NEWS

The Case for Unilateral Disarmament in the Trade Wars

U.S.-led multilateral trade accords do indeed look grim after the defeat of fasttrack. But that doesn’t mean that free trade itself is on the ropes. A large portion of the world’s trade liberalization in the last quarter-century has been unilateral. Those countries that lower trade barriers of their own accord not only profit themselves, but also often induce the laggards to match their example. The most potent force for the worldwide freeing of trade, then, is unilateral U.S. action. If the United States continues to do away with tariffs and trade barriers, other countries will follow suit—fast- track or no fast-track.

To be sure, the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade, the World Trade Organization, and other multilateral tariff reductions have greatly contributed to global wealth. The WTO has become the international institution for setting the “rules” on public and private practices

But the good news is that even if organized labor, radical environmentalists, and others who fear the global economy continue to impede fast-track during Congress’s next session, they cannot stop the historic freeing of trade that has been occurring unilaterally worldwide.

From the 1970s through the 1990s, Latin America witnessed dramatic lowering of trade barriers unilaterally by Chile, Bolivia, and Paraguay; and the entire continent has been moving steadily toward further trade liberalization. Mercosur’s recent actions are a setback, but only a small one—so far.

Latin America’s record has been bettered by unilateral liberalizers in Asia and the Pacific. New Zealand began dismantling its substantial trade protection apparatus in 1985. That effort was driven by the reformist views of then-Prime Minister David Lange, who declared, “In

they do today if people could consume only those goods and services produced in their own states. The world could similarly benefit from free trade among countries.

To better understand economists’ view of trade, let’s continue our parable. Suppose that the country of Isoland ignores the advice of its economics team and decides not to allow free trade in steel. The country remains in the equilibrium without international trade.

Then, one day, some Isolandian inventor discovers a new way to make steel at very low cost. The process is quite mysterious, however, and the inventor insists on keeping it a secret. What is odd is that the inventor doesn’t need any workers or iron ore to make steel. The only input he requires is wheat.

CHAPTER 9 APPLICATION: INTERNATIONAL TRADE |

199 |

|

|

|

|

the course of about three years we changed from being a country run like a Polish shipyard into one that could be internationally competitive.”

Since the 1980s, Hong Kong’s and Singapore’s enormous successes as free traders have served as potent examples of unilateral market opening, encouraging Indonesia, the Philippines, Thailand, South Korea, and Malaysia to follow suit. By 1991 even India, which has been astonishingly autarkic for more than four decades, had finally learned the virtue of free trade and had embarked on a massive lowering of its tariffs and nontariff barriers.

In Central and Eastern Europe, the collapse of communism led to a wholesale, unilateral, and nondiscriminatory removal of trade barriers as well. The French economist Patrick Messerlin has shown how this happened in three waves: Czechoslovakia, Poland, and Hungary liberalized right after the fall of the Berlin Wall; next came Bulgaria, Romania, and Slovenia; and finally, the Baltic countries began unilateral opening in 1991. . . .

U.S. leadership is crucial to maintaining the trend toward free trade. Such ultramodern industries as telecommunications and financial services gained their momentum largely from unilateral

openness and deregulation in the United States. This in turn led to a softening of protectionist attitudes in the European Union and Japan.

These developed economies are now moving steadily in the direction of openness and competition—not because any officials in Washington threaten them with retribution, but because they’ve seen how U.S. companies become more competitive once regulation and other trade barriers have fallen. A Brussels bureaucrat can argue with a Washington bureaucrat, but he cannot argue with the markets. Faced with the prospect of being elbowed out of world markets by American firms, Japan and Europe have no option but to follow the U.S. example, belatedly but surely, in opening their own markets.

The biggest threat to free trade is not the loss of fast-track per se, but the signal it sends that Americans may not be interested in lowering their trade barriers any further. To counteract this attitude, President Clinton needs to mount the bully pulpit and explain the case for free trade—a case that Adam Smith first made more than 200 years ago, but that continues to come under attack.

The president, free from the burdens of constituency interests that cripple many in Congress, could argue,

credibly and with much evidence, that free trade is in the interest of the whole world, but that, because the U.S. economy is the most competitive anywhere, we have the most to gain. The president could also point to plenty of evidence that debunks the claims of protectionists. The unions may argue that trade with poor countries depresses our workers’ wages, for example, but in fact the best evidence shows that such trade has helped workers by moderating the fall in their wages from technological changes.

Assuming that the president can make the case for free trade at home, the prospects for free trade worldwide remain bright. The United States doesn’t need to sign treaties to open markets or, heaven forbid, issue counterproductive threats to close our own markets if others are less open than we are. We simply need to offer an example of openness and deregulation to the rest of the world. Other countries will see our success, and seek to emulate it.

SOURCE: The Wall Street Journal, November 24, 1997, p. A22.

The inventor is hailed as a genius. Because steel is used in so many products, the invention lowers the cost of many goods and allows all Isolandians to enjoy a higher standard of living. Workers who had previously produced steel do suffer when their factories close, but eventually they find work in other industries. Some become farmers and grow the wheat that the inventor turns into steel. Others enter new industries that emerge as a result of higher Isolandian living standards. Everyone understands that the displacement of these workers is an inevitable part of progress.

After several years, a newspaper reporter decides to investigate this mysterious new steel process. She sneaks into the inventor’s factory and learns that the inventor is a fraud. The inventor has not been making steel at all. Instead, he has

200 |

PART THREE SUPPLY AND DEMAND II: MARKETS AND WELFARE |

been smuggling wheat abroad in exchange for steel from other countries. The only thing that the inventor had discovered was the gains from international trade.

When the truth is revealed, the government shuts down the inventor’s operation. The price of steel rises, and workers return to jobs in steel factories. Living standards in Isoland fall back to their former levels. The inventor is jailed and held up to public ridicule. After all, he was no inventor. He was just an economist.

The effects of free trade can be comparing the domestic price world price. A low domestic price country has a comparative

good and that the country will high domestic price indicates that has a comparative advantage in that the country will become an

When a country allows trade and of a good, producers of the good consumers of the good are worse allows trade and becomes an consumers are better off, and both cases, the gains from trade

A tariff—a tax on imports—moves equilibrium that would exist

Summar y

the gains from trade. Although

are better off and the government losses to consumers exceed these

effects that are similar to those of a however, the holders of the import revenue that the government would

arguments for restricting trade: defending national security, helping

preventing unfair competition, and trade restrictions. Although some

have some merit in some cases, that free trade is usually the better

Key Concepts

world price, p. 181 |

import quota, p. 189 |

Questions for Review

1.What does the domestic price that prevails without international trade tell us about a nation’s comparative advantage?

2.When does a country become an exporter of a good? An importer?

3.Draw the supply-and-demand diagram for an importing country. What is consumer surplus and producer surplus before trade is allowed? What is consumer surplus and producer surplus with free trade? What is the change in total surplus?

4.Describe what a tariff is, and describe its economic effects.

5.What is an import quota? Compare its economic effects with those of a tariff.

6.List five arguments often given to support trade restrictions. How do economists respond to these arguments?

7.What is the difference between the unilateral and multilateral approaches to achieving free trade? Give an example of each.

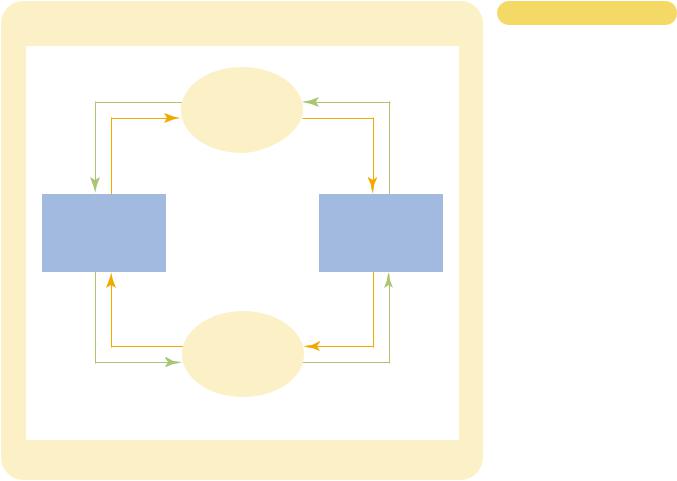

Flow of goods and services

Flow of goods and services Flow of dollars

Flow of dollars