Political Theories for Students

.pdf

C o m p a r i s o n T a b l e o f P o l i t i c a l |

T h e o r i e s |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Political Theory |

Who controls |

How is government put |

What roles do the |

|

government? |

into power? |

people have? |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Anarchism |

No government, the |

Not applicable |

Keep informed; |

|

people rule |

|

challenge any authority |

|

|

|

|

Capitalism |

Elected officials |

Elected by the masses |

Sustain the free market |

|

|

|

|

Communism |

The state |

Revolution |

Work for state’s benefit |

|

|

|

|

Conservatism |

Elected officials, with |

Popular vote of the |

Vote for representatives |

|

some appointed |

majority |

|

|

|

|

|

Fascism |

Dictator |

Overthrow or revolution |

Not interfere with the |

|

|

|

state |

|

|

|

|

Federalism |

Elected officials, |

Popular vote of the |

Vote for representatives |

|

majority of power in |

majority |

|

|

national leaders |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Feudalism |

Nobility |

Birth; feudal contract |

Work for nobles’ benefit |

|

|

|

|

Imperialism |

Nation–state |

Conquest |

Provide military and |

|

|

|

labor services |

|

|

|

|

Liberalism |

Individuals supported by |

Popular vote of the |

Vote; Bring about |

|

the people |

majority |

social change |

|

|

|

|

Libertarianism |

Restricted officials |

Group dissatisfied with |

Enjoy rights while not |

|

|

previous powers |

infringing on others |

|

|

|

|

Marxism |

Society |

Revolution |

Work for all individuals |

|

|

|

|

Nationalism |

State officials |

Crisis situation |

Support the nation |

|

|

|

|

Pacifism |

Officials supported by |

Peaceful removal of |

Protest peacefully unjust |

|

the people |

unjust regime |

laws or actions |

|

|

|

|

Patron–Client Systems |

Wealthy officials |

Overthrow or fall of |

Obey leader |

|

|

previous regime |

|

|

|

|

|

Populism |

Elected officials |

Elected by popular vote |

Pressure big business if |

|

|

|

unfair or unethical |

|

|

|

|

Republicanism |

Elected officials, |

Popular vote of the |

Vote; serve the state in |

|

majority of power in |

majority |

a crisis |

|

state leaders |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Socialism |

Society |

Revolution or evolution |

Share capital and means |

|

|

of other theories |

of production |

|

|

|

|

Totalitarianism |

Dictator |

Overthrow or Revolution |

Devote life to dictator |

|

|

|

and the state |

|

|

|

|

Utopianism |

State supported by the |

Cooperative founded by |

Tolerate differences; |

|

people |

dissatisfied group |

conform if needed |

|

|

|

|

x i i |

P o l i t i c a l |

T h e o r i e s |

f o r |

S t u d e n t s |

|

|

C o m p a r i s o n |

T a b l e o f P o l i t i c a l T h e o r i e s |

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Who controls production |

Who controls distri- |

|

|

|

|

of goods? |

bution of goods? |

Major figures |

Historical example |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The people |

The people |

Emma Goldman; |

Anti–globalization |

|

|

|

|

Mikhail Bukunin |

movement of late 1990s |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Owners of capital |

Owners of capital |

Adam Smith; John Locke |

United States |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The state |

The state |

Joseph Stalin; |

China, 1949–present |

|

|

|

|

Mao Tse–tung |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The owners of capital |

The owners of capital |

Edmund Burke; |

Great Britain in the |

|

|

|

|

Ronald Reagan |

1980s |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The state |

The state |

Benito Mussolini; |

Italy, 1922–1943 |

|

|

|

|

Adolf Hitler |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The market |

The market |

James Madison; |

United States |

|

|

|

|

Alexander Hamilton |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Nobility |

Nobility |

William the Conqueror; |

Medieval England |

|

|

|

|

Eleanor of Aquitaine |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Nation–state |

Nation–state |

Genghis Khan; |

Mongol Empire, |

|

|

|

|

Hernán Cortés |

1206–1368 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Private citizens |

Private citizens |

John Stuart Mill; |

Great Britain, |

|

|

|

|

William Gladstone |

1870–1900 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Private individuals |

Private individuals |

Ayn Rand; |

Austrian School of |

|

|

|

|

Russell Means |

Economics |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The people |

The people |

Karl Marx; |

Soviet Union, |

|

|

|

|

Vladimir Lenin |

1917–1924 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Owners of capital |

Owners of capital |

Ernest Renan; Johann |

Republic of Turkey, |

|

|

|

|

Gottfried Herder |

1923–present |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The people |

The people |

Mohandas Gandhi; |

U.S. civil rights |

|

|

|

|

Martin Luther King Jr. |

movement in 1960s |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Government and wealthy |

Government and wealthy |

Pope Adrian IV; |

Zaire, 1965–1997 |

|

|

businesspeople |

businesspeople |

Juan Perón |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The people |

The people |

William Jennings Bryan; |

People’s Party in U.S. |

|

|

|

|

George Wallace |

South in the 1890s |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The owners of capital |

The owners of capital |

Niccolò Machiavelli; |

Ancient Sparta |

|

|

|

|

John Jay |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Society |

Society |

Pierre–Joseph Proudhon; |

Tanzania, 1964–1985 |

|

|

|

|

Julius Nyerere |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The state |

The state |

Friedrich Nietzsche; |

Egypt, 1952–present |

|

|

|

|

Adolf Hitler |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The people, managed by |

The people, managed by |

Sir Thomas More; |

The Farm |

|

|

state |

state |

Robert Owen |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

P o l i t i c a l |

T h e o r i e s |

f o r |

S t u d e n t s |

x i i i |

Anarchism

OVERVIEW |

|

WHO CONTROLS GOVERNMENT? No government, the |

|

|

people rule |

||

The political theory of anarchism revolves around |

|||

HOW IS GOVERNMENT PUT INTO POWER? Not applicable |

|||

the ideal of noncoercion. Born with the rise of the |

|||

|

|||

nation–states in the eighteenth century, anarchism |

WHAT ROLES DO THE PEOPLE HAVE? Keep informed; |

||

has developed four major strains including mu- |

challenge any authority |

||

ualism, anarcho–individualism, anarcho–socialism, and |

WHO CONTROLS PRODUCTION OF GOODS? The people |

||

anarcho–communism. In the late twentieth century, an- |

|||

|

|||

archism has been adapted to the student, women’s, and |

WHO CONTROLS DISTRIBUTION OF GOODS? The people |

||

environmentalist movements, among others. Anar- |

MAJOR FIGURES Emma Goldman; Mikhail Bukunin |

||

chism has spawned experimental communities, peace- |

|||

|

|||

ful protest, violent rebellion, and a wide and varied |

HISTORICAL EXAMPLE Anti–globalization movement of |

||

literature dedicated to the achievement of human |

late 1990s |

||

liberty. |

|

||

HISTORY

Popular use of the term “anarchy” tends to portray an image of chaos, of bombs and fires and looting, of crisis overtaking order. Hollywood dystopias and fringe rock bands have played into this stereotype with glee. Although some anarchists desired political revolution over political reform, many advocated peace. Equating anarchy with chaos obscures a rich and serious tradition of political thought and the subtle variations that have evolved from it.

The ideas of anarchism began in the distant past. When Plato (428–348 B.C.) wrote his Republic in the fourth century B.C., he advocated a centralized government coordinating a communist society; his fellow

1

A n a r c h i s m

CHRONOLOGY:

1793: William Godwin’s Enquiry Concerning Polit-

ical Justice is published.

1840: What Is Property? by Pierre–Joseph Proudhon appears.

1843: Phalanx, New Jersey, becomes the first Fourierist experimental community.

1852: Josiah Warren’s Practical Details in Equitable

Commerce appears.

1879: Peter Kropotkin founds the journal Le Révolté in Switzerland.

1881: Benjamin Tucker founds the newspaper Liberty, Not the Daughter but the Mother of Order.

1882: Mikhail Bakunin’s God and the State is published.

1923: Emma Goldman’s My Further Disillusionment

with Russia appears.

1927: Nicola Sacco and Bartolomeo Vanzetti are executed in the United States.

1973: For A New Liberty by Murray Rothbard appears.

1982: Murray Bookchin’s Ecology of Freedom is completed.

Greek philosopher Zeno (c. 335–c. 263 B.C.), founder of the Stoa school, responded by championing a stateless society as the ideal way for humans to live together. The absence of government described by Zeno might be called one of the earliest articulations of anarchism. This theme found repetition among different peoples and eras for centuries.

A later precursor to anarchism developed after the English Civil War in the form of the Digger Movement. The founder of this dissenting group was Gerrard Winstanley (c. 1609–1660), an unorthodox Christian who identified God with reason. In his 1649 pamphlet Truth Lifting Up Its Head Above Scandals, Winstanley proposed principles for the Diggers, principles that later served as foundational assumptions for many anarchists. He noted the following: power corrupts, property hinders freedom, authority and property cause crime, and freedom requires the op-

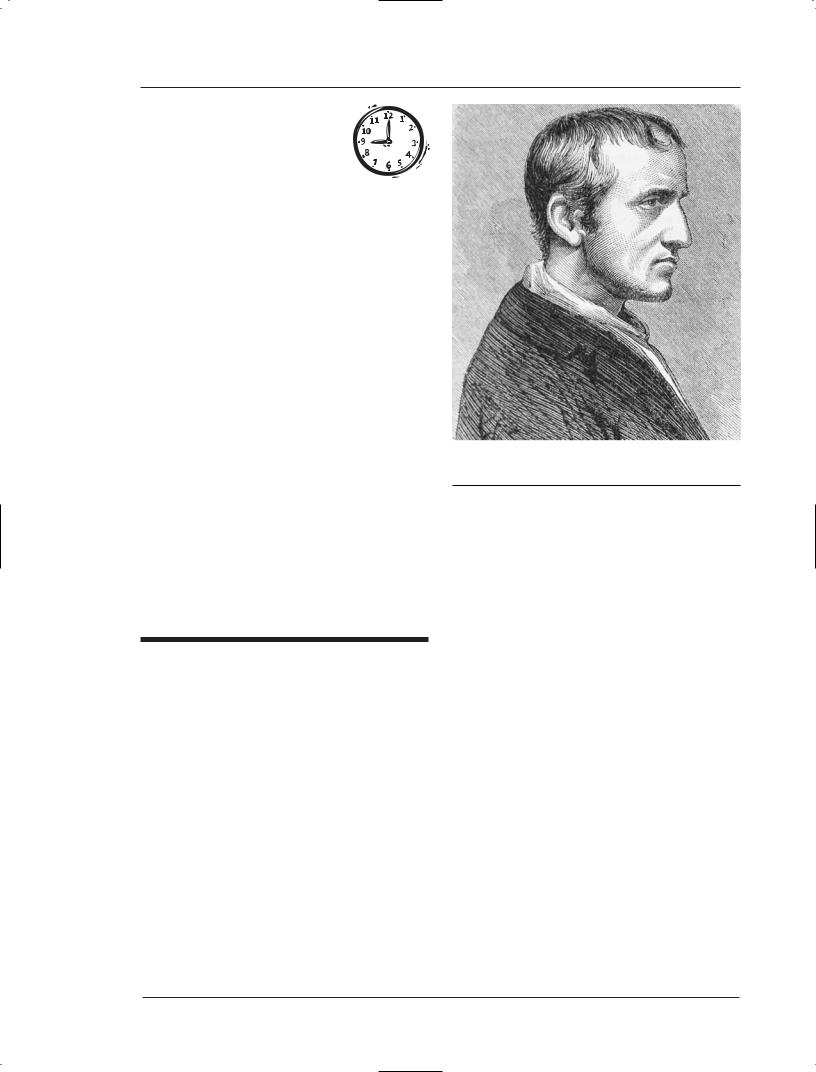

William Godwin. (The Library of Congress)

portunity for people to live without laws or rulers according to their own consciences. He and his followers also taught nonviolent activism. In 1649, they occupied an English hillside, created a communist community there, and offered passive resistance to local landlords. Although local opposition eventually crushed the movement and forced Winstanley into obscurity, the Diggers provided a direct antecedent to later anarchist thought and practice.

The term “anarchy” was not used to describe the nonexistence of governmental coercion until 1703, however, when the French traveler Louis Armand de Lahontan (1666–1715) in his book New Voyages in North America described Native American societies that functioned without a state apparatus. He noted that they lived without governments or codified laws: in other words, “in anarchy.” Thus the modern sense of the term was born.

William Godwin

Anarchism as a political theory and movement appeared in the late eighteenth century and paralleled the rise of nationalism tied to the era of great na- tion–states. The British philosopher and novelist William Godwin (1756–1836) offered the first systematic treatment of anarchist thought in his 1793 work An Enquiry Concerning Political Justice and its Influence on General Virtue and Happiness. In this

2 |

P o l i t i c a l |

T h e o r i e s |

f o r |

S t u d e n t s |

A n a r c h i s m

book he argued that humans were evolving toward increasing perfection, but institutions such as the government hindered individuals’ use of reason. By removing such hindrances as the state, enlightened and educated people could live peacefully in small, cooperative communities and devote themselves to self–betterment. Godwin’s work found resonance in the political theory community. It also influenced the literary establishment; Godwin’s daughter by the feminist leader Mary Wollstonecraft (1759–1797) was Mary Shelley (1797–1851), author of Frankenstein and wife of Romantic poet Percy Bysshe Shelley (1792–1822). Percy Shelley adopted Godwin’s theme in his own work and gave anarchism an influential, poetic voice.

Godwin’s concept of small, cooperative communities thriving in the absence of government control inspired French theorist Charles Fourier (1772–1837). Many of his concerns about the coercion, mechanization, dehumanization, and class schism of society previewed concerns later raised by critics of the Industrial Revolution. His belief in channeling humans’ natural passions to achieve social harmony, and the practical means he suggested for achieving it, became known as Fourierism.

Fourierism

Unlike other collectivists of the era, who believed the state needed to own the means of production in the economy, Fourier called for anti–authoritarian socialism based on private property ownership and individual needs and desire. He simply wanted a well–ordered agricultural society, one based on cooperation and gender equality. Fourier devised with almost mathematical precision his plan for achieving harmony: the phalanx, an economic unit of 1,620 people who divided labor among themselves according to ability. He wrote and spoke about his blueprint for utopia, and followers and newspapers responded enthusiastically. Unfortunately, Fourier did not live to see his ideas applied in concrete settings. After his death in 1837, adherents such as Albert Brisbane (1809–1890) and Horace Greeley (1811–1872) transplanted Fourierism to the United States and in 1843 founded Phalanx, New Jersey, the first of almost thirty experimental communities based on Fourier’s vision. Christian, but nonsectarian, these colonies organized themselves as cooperatives with equalized wages and supported themselves by the work of members and funds from non–resident stockholders. The communities encouraged traditional values such as monogamy and family, but also encouraged gender equality: several directors or presidents of Fourierist communities, in fact, were women.

BIOGRAPHY

William Godwin

The English William Godwin originally studied to be a minister but, after several years of practicing the profession, left his preaching due to religious doubts and set out to be a writer. During his day he was known as much for his personal life as for his political views. He was married to Mary Wollstonecraft, a political theorist in her own right, and also an early activist for women’s rights. She died in childbirth in 1801; the child she bore grew up to be Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley, author of the 1818 horror classic Frankenstein. The daughter Mary tested her father’s liberal views when she fell in love and ran away with Percy Bysshe Shelley, the Romantic poet, who at the time was a married man. The couple was ostracized due to their scandalous behavior. After his wife’s suicide, Shelley married Mary, however, and the scandal quieted. Shelley credited his father–in–law with opening his eyes to anarchism; in turn, Godwin’s influence gained entrance into the world of poetry and literature.

Godwin’s Enquiry Concerning Political Justice

(1793) explored his belief that humans were rational creatures and, through reason, could live together in peace without the need for institutions such as the law and the state. He asserted that humans were perfectible, and any mistakes they made could be traced to mistaken beliefs. With proper information backing true beliefs, he continued, humans would better and eventually perfect themselves. He criticized the state and other coercive institutions for keeping citizens ignorant and thereby denying them the opportunity to become more than what they are. His novels such as

Adventures of Caleb Williams (1794), St. Leon (1799), and Fleetwood (1805) illustrated his political views and moral theory. Godwin died in London in 1836. His works remain the first comprehensive articulation of anarchism.

The best symbol of Fourierism was Brook Farm, an experimental community in West Roxbury, Massachusetts. The community began in 1841 as a Unitarian venture but converted to a Fourierist phalanx in 1844. Brook Farm gained international celebrity

P o l i t i c a l |

T h e o r i e s |

f o r |

S t u d e n t s |

3 |

A n a r c h i s m

status thanks to its membership, which included some of the era’s intellectual elite, including Nathaniel Hawthorne, Ralph Waldo Emerson, Margaret Fuller (1810–1850), and Orestes Brownson (1803–1876). The Fourierist newspaper Harbinger began publication at Brook Farm as well. After the central building was destroyed by fire, the colony fell into economic hardship and eventually disbanded. Its fame lived on, however, in the works and lives of its former members. Though certainly not the only attempts to create utopia through experimental communities, Fourierism did represent one of the earliest and most successful attempts at implementing the kind of non–coercive framework Godwin advocated.

Pierre–Joseph Proudhon

After Godwin’s theory and Fourier’s practice, the next dramatic step in the story of anarchism appeared with the French journalist Pierre–Joseph Proudhon (1809–1865).

The Frenchman Proudhon was haunted by the spectre of poverty all of his life. Born to a poor family, Proudhon worked hard to obtain scholarships in order to continue his education, but eventually was forced to abandon them in order to work. His later life found him once again with little income or economic opportunities. His experience with financial hardship helped to form his view of property as an exploitative system. He first gained public recognition writing about the abuses inherent in the institution of property and his anarchist solutions to these inequalities in the 1840 work What Is Property? He followed this publication with many other works, the highlights among which are System of Economic Contradictions; or The Philosophy of Poverty (1846), General Idea of Revolution in the Nineteenth Century (1851), and the three– volume Of Justice in the Revolution and the Church

(1858). In his writings he gave the words anarchy and anarchist their modern meaning and opened the door for an identifiable anarchist movement across the West.

Proudhon’s activism began as a vocal member of the Constituent Assembly in France, in which he voted against a constitution for the simple fact that it was a constitution. His 1840 What Is Property? used the term “anarchy” to mean the absence of sovereignty and “anarchist” to mean one who advocates anarchy. His later works further explored the subject. Proudhon made waves with his attack on the state in general and representative democracy in particular. To replace these systems, he advocated the cooperation of industrial and agricultural communities and the commercial use of labor checks instead of money; labor checks, he explained, would represent how much labor went into the

production of a given product, and thus would assure that the exchange rate of products would be determined by the labor they represent, to the benefit of the workers. He termed this cooperative system with its corresponding labor theory of value “mutualism.”

Mutualism

After the Revolution of 1848 in France, Proudhon, who had worked his way up to the editorship of a successful newspaper, was elected to the Constituent Assembly. He sensed an historic opportunity to make changes on behalf of the workers, and therefore proposed establishing a national bank to reorganize the credit system to liberate and empower the working class. His efforts failed. He went on to think outside of the French system and imagine a replacement, one with loosely federated communities uniting by free choice around certain common assumptions about the labor theory of value and the endeavor to reach common societal goals. His work criticized legal government’s centralization of authority in officials and fixed, general rules that discouraged individual judgments and broke down communal ties—in short, stunting individuals’ growth and their opportunity to cooperate with others for mutual benefit. He is best known as the father of mutualism, the variety of anarchism in between individualism’s reliance on private property and collectivism’s wariness of it.

Proudhon’s mutualist anarchy, with its focus on laboring classes and their emancipation from economic coercion, contrasted with another contemporary version of anarchism, individualism. Individualist anarchists emphasized the emancipation of the individual from the political coercion of the state. Two pioneers of this variation of anarchism included Max Stirner (1806–1856) and Benjamin R. Tucker (1854– 1939). The German philosopher Stirner came to the conclusion that the state should not exist because it deprives individuals of the qualities that make them unique. Any time people are treated as collectives rather than different individuals, he argued, violence is done against them. In order to rule, the state requires servants who obey. Without this obedience, people become individuals and the state ceases to exist. In his 1844 work The Ego and his Own, Stirner set out his views on individuality, collectivity, the will of the state, and the way in which individuals could break free of submission and thus rid themselves of the institutions of coercion such as the state.

Anarchism in the United States

Anarchism crossed the ocean in the nineteenth century and came to the United States in the persons

4 |

P o l i t i c a l |

T h e o r i e s |

f o r |

S t u d e n t s |

A n a r c h i s m

BIOGRAPHY

Lysander Spooner

Lysander Spooner was a reformer by nature. Born in Athol, Massachusetts in 1808, Spooner worked on his father’s farm until the age of twenty–five. He then began to study law under two prominent Massachusetts jurists, John Davis and Charles A. Allen. When he learned that the law required non–college–educated candidates to the bar to study law for an extra three years above what was required for university students, he campaigned against the statute and ultimately achieved its repeal. As a young lawyer, he took part in the free thought campaign of the times and wrote a popular tract against religious orthodoxy, The Deist’s Reply to the Alleged Supernatural Evidences of Christianity (1836).

Spooner’s greatest contribution to anarcho–indi- vidualist thought was his critique of the U.S. Consti- tution—and, by implication, all constitutions—as a mechanism of special privileges through which minority groups could exploit others. After the U.S. financial panic of 1837, Spooner observed how political and governmental bodies inserted themselves into private banking through complicated restrictions and legal escape mechanisms. His 1843 work Constitutional Law Relative to Credit, Currency and Banking

offered a lasting addition to free banking literature and the anarchist cause. His interest in individual liberty also led him to oppose slavery and write for the abolitionist cause.

He attacked the U.S. government’s monopoly on the mail system by noting that the Constitution did not provide the state the sole and exclusive right to establish postal service for the nation. He viewed it not only as a financial evil, but a moral one as well, noting the power it gave the state to be the only conduit for information. Spooner then established a competing business in 1844, the American Letter Mail Company, which promptly proved it could deliver mail faster at a lesser cost. In 1845, a congressional act imposed heavy penalties for independent mail companies and Spooner was forced to close his doors. Spooner continued to publish books and pamphlets prolifically on a number of topics, as well as contribute articles to Benjamin Tucker’s anarchist newspaper Liberty. Until his death, his writings on an expansive number of issues and his activism in concert with his publishing ventures made Spooner one of the most important anarcho–individualists in history.

of Josiah Warren (1798?–1874), Lysander Spooner (1808–1887), and Benjamin R. Tucker (1854–1939). Warren had followed the socialist utopian teachings of Robert Owen (1771–1858), but soon became convinced of what he called “the sovereignty of the individual” against the claims of the group. Like Godwin before him, Warren believed that products should be valued by the amount of labor it took to produce them. Based on this conviction, Warren opened several so–called “equity stores” where goods could be exchanged based on the labor they required to produce. Cost, in effect, served as the limit of price. His efforts led him to found several experimental colonies based on his anarchist principles, including the highly visible Modern Times, which endured on Coney Island, New York from 1851 until approximately 1860. He published his views on anarchist theory and practice in his 1852

Practical Details in Equitable Commerce, his 1863 True Civilization, and other works.

Lysander Spooner Lysander Spooner, like Warren, was both an activist and a political philosopher. A critic of the U.S. system and its legislative process, Spooner believed the Constitution created opportunities for minority groups to exploit others through the use of special privileges. His training and practice as an attorney afforded him the tools to dissect the finer points of statutes. In 1843, he warned that artificial restrictions were closing the door to private, competitive credit in Constitutional Law Relative to Credit, Currency and Banking, which influenced the free banking movement in the United States for decades. He noted that acts of incorporation helped individuals to escape their contractual obligations by hiding behind the fictional face of a corporation. When Spooner formed the American Letter Mail Company in 1844 to compete with the U.S. Post Office, he proved that a private company could deliver mail faster and at a lower price than could a government monopoly—and the United States promptly

P o l i t i c a l |

T h e o r i e s |

f o r |

S t u d e n t s |

5

A n a r c h i s m

outlawed his venture. His two–part The Unconstitutionality of Slavery in 1845 and 1846, among his many other publications, explored his understanding of natural law, justice, and government, and set the stage for his criticisms of the institutions of majority rule. His pamphlet series No Treason and 1882’s Natural Law further cemented him as a giant of American anarchism.

Benjamin Tucker American journalist Benjamin R. Tucker drew inspiration from Josiah Warren’s “sovereignty of the individual” idea and in turn led a publishing venture that supported and galvanized a flourishing anarchist movement in the United States. Tucker’s individualist anarchist newspaper Liberty, Not the Daughter but the Mother of Order, with its title taken from a quote from Pierre–Joseph Proudhon, ran from 1881 to 1908. As editor, Tucker wrote for the paper, but he also published the work of Lysander Spooner, Victor Yarros, J. William Lloyd, Vilfredo Pareto (1848–1923), and many others. Diverse and visible readers such as Walt Whitman (1819–1892), George Bernard Shaw (1856–1950), and H. L. Mencken (1880–1956) praised Liberty for providing a quality forum for American radicalism. The paper served to unify American individualists and had a great impact on U.S. libertarianism through the twentieth century. Due to its popularity and longevity, Liberty remains one of the most thorough and wide– ranging collections of individualist anarchist writing in existence.

Russia

The nineteenth century also brought anarchism to Russia. Mikhail Bakunin (1814–1876) helped to take anarchist thought from the theory books to the street. He prized human freedom and dismissed its enemies, which he believed included the state—even when it appeared as a representation of the people—and all forms of religion. He predicted that the future of Europe included increasing state powers and economic monopoly unless someone took action. Bakunin tried; he advocated revolution and organized secret societies under the conviction that a few people could change the system and liberate all individuals. His goal was to create a society arranged from the bottom up through collective, social property; he opposed the centralized state necessary for the implementation of communism, however, and instead supported free association. His theories put him in direct opposition to another revolutionary thinker, Karl Marx, and inspired socialist movements in France, Italy, Switzerland, and, most notably, Spain, where it impacted the country’s civil war in the late 1930s.

Peter Kropotkin Unlike Bakunin, fellow Russian Peter Kropotkin (1842–1921) was an anarcho– communist who believed in the coordination of industry and agriculture; like Bakunin, he feared the power of the centralized state, and so he believed that small communities should control their economies. Kropotkin’s main interest rested in finding a scientific justification for anarchism. His 1902 Mutual Aid: A Factor of Evolution challenged Charles Darwin’s (1809–1882) assumptions about evolution and suggested that mutual aid played as important a role in society as the struggle for survival. He saw cooperation as a fundamental aspect of human nature, and expected that any process of self–realization would lead an individual not to isolation, but to greater harmony and solidarity with others. Kropotkin was not impressed with the final result of the Russian Revolution of 1917 and criticized the fact that power continued to be centralized in an impersonal authority, the party dictatorship, rather than in the councils of the workers, peasants, and communities. Kropotkin’s voice brought anarchism into the twentieth century.

For a short time at the turn of the century, a phenomenon known as anarcho–syndicalism existed. Based on the French syndicat, or union, the idea was to infuse the movement with stabilizing organization by infiltrating the union system and taking over its infrastructure. The most successful example of anar- cho–syndicalism was Fernand Pelloutier’s Fédération des Bourses du Travail. These French labor exchanges provided workers the opportunities to seek jobs and, at the same time, receive anarchist propoganda. Beginning in about 1895, this had great success in moving anarchism in a positive direction. The French model inspired similar organizations in Spain and elsewhere. By the time of World War I, however, this movement began its decline everywhere but Spain, where it played a key role in that country’s civil war.

Germany

In Germany, Gustav Landauer, a generation younger than Kropotkin, felt the impact of the German School of Romanticism as embodied in figures such as Arthur Schopenhauer (1788–1860), Friedrich Nietzsche (1844–1900), and Henrik Ibsen (1828–1906). Landauer’s contribution to anarchism was the blending of Romantic sensibilities with anarchist politics. He was fascinated by the notion of the human psyche resting beneath consciousness, and he prioritized the spiritual need for rootedness and community that pulled individuals together. He believed the society of the times—cold, mechanical, industrialized, impersonalized, and centralized—could not replace the relationships that had been lost, and he called for an uprising

6 |

P o l i t i c a l |

T h e o r i e s |

f o r |

S t u d e n t s |

A n a r c h i s m

to replace the authoritarian state with the wholeness of folk community. The revolution he supported was not a violent cause of politics, however, but an internal change of attitude, a rebirth within individuals. In his words: “The state is a condition, a certain relationship between human beings, a mode of human behavior; we destroy it by contracting other relationships, by behaving differently.” Landauer did participate briefly in the Bavarian Revolution of 1917–1919, but later in 1919 was stoned to death by state troops in Munich.

Emma Goldman

Emma Goldman’s (1869–1940) activist anarchism is more difficult to assign to a specific country. A native of Lithuania, Goldman immigrated to the United States in 1886 and was deported to Russia in 1919. She took part in the Spanish Civil War in 1936 and died in Canada in 1940. This woman of the world is best known for introducing feminism to the anarchist tradition. Her controversial views included promoting birth control and obstructing the draft. Together with Alexander Berkman (1870–1936), Goldman published the short–lived but highly visible anarchist paper Mother Earth. Goldman based her activism on Kropotokin’s anarcho–communism but admitted that the theory might be less than successful in actual practice. This did not dissuade Goldman, however, from her attacks on the concentration of political and economic power. She urged women in particular not to be satisfied with a vote that meant little in a system stacked against the individual. In the process, her controversial and public protest brought new sensibilities to the movement.

Sacco and Vanzetti

Often when anarchism is discussed, Nicola Sacco (1891–1927) and Bartolomeo Vanzetti (1888–1927) are the first names mentioned. The seven–year trial of Sacco and Vanzetti was perhaps the most famous trial in U.S. history; it certainly was the most famous trial of the first half of the twentieth century. One of the keys to the emotions and politics surrounding the case rested in the fact that both Sacco and Vanzetti were anarchists.

Both Sacco and Vanzetti were Italian emigrants who came to the United States to practice their trades. Sacco was a shoemaker and Vanzetti was a fishmonger. Both became involved with the American anarchist movement and avoided the draft for World War I. On April 15, 1920, in Braintree, Massachusetts, a shoe company’s paymaster and his guard were shot and killed by two men who stole over $15,000 from their victims’ company. Local police investigated and linked a car with the crime. When Sacco, Vanzetti,

and two others arrived at the garage to claim the car, the police arrested them and charged them with the crime.

The case seemed problematic: Sacco and Vanzetti were armed when arrested, but neither had a criminal record and no sign of the stolen money could be traced to them. Sentiment against such so–called “radicals” as anarchists ran high, however, and circumstantial ev- idence—much of which was later discredited— mounted against Sacco and Vanzetti. The trial received further controversy due to the conduct of Judge Webster Thayer. Nonetheless, the Massachusetts State Supreme Court stood behind the conviction of Sacco and Vanzetti and the governor chose not to pardon them. Despite worldwide sympathy demonstrations and political protests, Sacco and Vanzetti were executed on August 22, 1927. Their true guilt or innocence remains uncertain. Their death made them anarchist martyrs, however, and their story was translated into songs such as Joan Baez’s “The Ballad of Sacco and Vanzetti” (an anthem of the 1960s U.S. counterculture), plays such as Maxwell Anderson’s Gods of the Lightning, novels such as Upton Sinclair’s Boston, and poems such as the sonnets of Edna St. Vincent Millay.

The Twentieth Century

The twentieth century brought feminist and environmental variations on the anarchist theme, among others. Longer–lived strains such as individualist anarchism also gained a second wind. Murray Rothbard (1926–1995) was one of the theorists who brought individualist anarchism to public attention in the late twentieth century. Rothbard came of age intellectually in the Austrian School of Economics, which was pioneered by Carl von Menger (1840–1921) and Ludwig von Mises (1881–1973) in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century. He took that school’s emphasis on human unpredictability and spontaneous order, as well as its condemnation of centralized planning, and followed it to an anarchist conclusion. Believing that all state intervention is not only disastrous but also based on unconscionable force, Rothbard produced such works of theory as Man, Economy and State

(1962), Power and the Market (1970), For A New Liberty (1973), and Ethics of Liberty (1982). His work brought him great prominence in the emerging American Libertarian Movement before his death in 1995.

From its roots in ancient times through its development in France, England, and the United States, as well as its relationship with revolts such as the Russian Revolution and Spanish Civil War, anarchism has been a theory of many manifestations. As a coherent movement, however, anarchism is rela-

P o l i t i c a l |

T h e o r i e s |

f o r |

S t u d e n t s |

7 |

A n a r c h i s m

tively young, which has meant that theorists and activists have influenced each other significantly, even when writing or working in other countries and situations. As new concerns such as environmentalism confront individuals, the tradition evolves to encompass new voices and positions. Despite the movement’s adaptability, the repudiation of coercion holds all of anarchism’s diverse strains together across the years and miles.

THEORY IN DEPTH

Anarchist theorists have covered the spectrum from those who believed property is theft to those who believed property is an inalienable natural right, from those who wished to stir revolution to those who embraced pacifism. Others incorporated the agendas of other movements: anarcho–feminism appeared in hand with the women’s suffrage movement, and an- archo–environmentalism emerged with the Green Movement. At its core, all strains of anarchism deal with the question of how to eliminate coercion. The four principle divisions of anarchist theory that sprang up in answer to this question were individualism, mutualism, socialism, and communism.

Godwin and Noncoercion

The first systematic exploration of the anarchist theme of noncoercion appeared in William Godwin’s 1793 English work An Enquiry Concerning Political Justice and its Influence on General Virtue and Happiness. Any examination of anarchism must begin there. The former minister set out his vision of the ideal community and explained that its existence implied the dissolution of government. Godwin’s vision of societies based on consent, cooperating with one another, and working and sharing the wealth equally, sounded almost utopian. With the members in agreement, no external state or mechanism of law would be necessary:

Government can have no more than two legitimate purposes, the suppression of injustice against individuals within the community, and the common defence against external invasion. The first of these purposes, which alone can have an uninterrupted claim upon us, is sufficiently answered, by an association of a jury, to decide upon the offences of individuals within the community, and upon the questions and controversies, respecting property, which may chance to arise.... But there will be no need of any express compact, and still less of any common center of authority, for this purpose. General justice, and mutual interest, are found more capable of binding men, than signatures and seals.... This is one of

the most memorable stages of human improvement. With what delight must every well informed friend of mankind look forward, to the auspicious period, the dissolution of political government, of that brute engine, which has been the only perennial cause of the vices of mankind...

Anarcho–individualism

Anarchist individualist theory begins with the individual as the building block of the world. Individualists believe that each person has rights—some would call these natural rights—that no other person or group of people can ever violate. These often include rights such as the individual’s right to live, to control his or her body, and to speak his or her mind. Theorists in this tradition also believe that people have rights to certain actions around them, including the rights to be creative and to own what they have produced. If people are independent thinkers and producers, then, the main way individuals interact socially is through ex- change—buying, selling, and/or trading—and contract, where two or more individuals agree to an action with reciprocal duties, responsibilities, and gains.

Warren’s Vision

Josiah Warren’s vision of anarcho–individualism may have been the first fully articulated version of the theory, but it was not indicative of the tradition as a whole for two reasons. First, Warren argued that the individual should follow his or her wishes only; other individualists recognized that religious, moral, and social rules might have a part to play in individuals’ decision making. Second, Warren remained tied to the labor theory of value and its idea of using cost to determine just price for items.

Josiah Warren was concerned with the inequities and imbalances of power created by property ownership. In his 1852 book Practical Details in Equitable Commerce, he offered a different interpretation of legitimate property: individuals owned the products of their own labor. This eliminated more passive earnings such as rent on lands or interests on loans and leveled the playing field for individuals within the framework. Warren reiterated that his blueprint for a new system held individuality as its highest goal:

I will not now delay to detail the reasonings which led to the conclusion that SOCIETY MUST BE SO RECONSTRUCTED AS TO PRESERVE the sovereignty of every individual inviolate. That it must avoid all combinations and connections of persons and interests, and all other arrangements, which will not leave every individual at all times at LIBERTY to dispose of his or her person, and time, and property, in any manner in which his or her feelings or judgement may dictate, WITHOUT INVOLVING THE PERSONS OF OTHERS.

8 |

P o l i t i c a l |

T h e o r i e s |

f o r |

S t u d e n t s |